My SciELO

Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Enfermería Global

On-line version ISSN 1695-6141

Enferm. glob. vol.20 n.63 Murcia Jul. 2021 Epub Aug 02, 2021

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/eglobal.445631

Originals

Design and validation of an educational video for HPV prevention

1 Facultad de Enfermería. Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla. México. javier.baez@correo.buap.mx

2 Facultad de Medicina. Universidad Autónoma de Chiapas, México.

Objective:

To design and validate an educational video for the prevention of HPV in young people, using the information, motivation and behavioral skills model.

Methodology:

The design of the present study consisted of six stages: 1.- descriptive literature review; 2.- analysis of interviews with the target population; 3.- placing the information obtained (literature and interviews) within the components of the information - motivation - behavioral skills model (IMB); 4.- script development, 5.- expert validation process, and 6.- pilot test.

Results:

Based on the previous steps, the video titled: “7 things you should know about HPV!” was designed, where two young people (a man and a woman) appear and answer, in a clear and simple way, seven questions about HPV, ending with a series of recommendations to prevent infection and promote responsible sexuality. Validation was carried out using a focus group of 10 young people gathered in an online platform and the content validity index (CVI), obtaining a value of .92, which is considered good and adequate to understand the basic aspects of HPV.

Conclusions:

The design and validation of a video for the prevention of HPV is a hermeneutical and systematic methodological process that promotes eclectic, heuristic, and innovative thinking for prevention and promotion of responsible sexuality in the young population.

Keywords: Validation Study; Audiovisual resources; Papillomavirus Infections

INTRODUCTION

Infection by human papillomavirus (HPV) is the main cause of cervical uterine cancer and other types of cancer, as well as anogenital warts in males and females, of highest incidence in the world in sexually active populations, with the highest infection rate in young people between 15 and 25 years old 1.

At a global level, the prevalence of HPV in women is estimated to be 11.7%, while in men, it is high in all world regions (21%) and the peak usually occurs a little later than in women 2. In Mexico, in the last week of the year 2019 and the first of 2020, there was a total of 24,055 cases, of which, 22,536 were of women and 1,519 were of men. In addition, Puebla and Chiapas ranked among the first fifteen states with the highest number of infected people at a national level, with a total of 1,264 3.

Among the main risk factors for developing an HPV infection are tobacco use (generally in women), early unprotected sexual relations (vaginal, oral, anal, and/or any other type of genital contact), number of sexual partners, women with a high number of pregnancies, childbirth delivery at an early age, depression of the immune system, prolonged use of contraceptives, and poor nutrition, as well as a lack of knowledge about this infection 4.

In this sense, recent studies conducted in Turkey, Brazil, Mexico, and the United States agree that the main lack of knowledge in the population is with reference to: what is HPV?, who carries the virus?, the application of vaccines in both genders, and the most common stereotypes. 4)(5)(6)(7)(8)(9) These results are related to risky sexual behaviors, such as unprotected vaginal and/or anal intercourse, multiple sexual partners, and drug use during sexual relations 10,11.

Based on the above, it is evident that knowledge about this infection plays an important role in the way that people could take responsibility for their sexual life. This is why different studies have shown that fostering knowledge about HPV among young people and adolescents, both on promotion and prevention, through educational audiovisual resources (videos) that reflect real situations where a group of young people learn to reduce the risk of suffering from sexually transmitted infections (STIs), results favorable for modifying: myths, beliefs, and forms of behavior that have influenced their formation, and thus contribute to the manifestation of self-responsibility in the care of their sexual lives in the adult stage through the development of specific behavioral skills, such as getting HPV detection tests, the use and negotiation of condoms, and convincing vulnerable groups to get vaccinated 13)(14)(15.

This is where the design and validation of educational videos with a theoretical basis becomes relevant, which allows to understand and generate changes in health behavior. This is the reason why the information-motivation-behavioral skills (IMB) model of Fisher and Fisher 16 is used in the present study, because it proposes that adopting preventive behavior requires increasing the knowledge, motivation, and skills related to such behavior. This model indicates that the gain of information is a necessary precursor for adopting preventive behavior and that motivation to change is more important if one learns how to perform such behavior. The model establishes that behavioral skills related to prevention actions are a common final pathway of information and motivation. The gain of behavioral skills to achieve this change becomes decisive when prevention actions require complex abilities, such as getting HPV detection tests, using and negotiating the use of condoms with a partner, and getting vaccinated among vulnerable groups 17,18.

Considering the above, the following objective was proposed: to design and validate an educational video for the prevention of HPV in young people using the information-motivation-behavioral skills model.

METHODOLOGY

The design of the present study consisted of six stages: I.- descriptive literature review; II.- analysis of interviews with the target population; III.- placing the information obtained (literature and interviews) within the components of the information-motivation-behavioral skills (IMB) model; IV.- script development, V.- expert validation process, and VI.- pilot test.

(I) Descriptive literature review

The first step consisted in performing a literature search of the knowledge about HPV and the main educational tools used for prevention and promotion of sexual health in the young population published in the last five years (2015 to 2020) in Spanish, English, and Portuguese. The search was conducted in scientific databases (EBSCO, PUBMED, SCOPUS, CINAHL, WEB OF SCIENCE) and the digital repository of the Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACYT; National Council of Science and Technology) using boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT) and key words and Health Science Descriptors (DeCS), where search strings were constructed. We also created a study analysis matrix containing: objective, design (population, sample), results, conclusions, and reference data.

(II) Analysis of interviews with the target population

The second step consisted in conducting 10 semistructured interviews with the target population (five men and five women from the states of Puebla and Chiapas), which were recorded and analyzed by the research team. The objectives were: 1.- to determine what knowledge they had about HPV and 2.- to identify the characteristics that the messages should have, as well as the duration and form of the video, in order to learn about HPV.

(III) Placing the information obtained within the components of the IMB model

The third step involved placing the information obtained from the scientific literature and the conducted interviews with the target population within the components of the information-motivation-behavioral skills (IMB) model for a preliminary design of the video. We used the proposal by Menacho and Blas 17, adapted by Báez, Márquez, Onofre, Benavides and Flores 19. This consisted in constructing a relationship matrix of the concepts of the theoretical framework, the components of the video (information and content), and the expected results based on the objective to be achieved, with the aim of planning the development of this educational audiovisual resource with the theoretical proposal.

(IV) Script development

The fourth step consisted in the development of the script through multidisciplinary work, including a graphic designer, a communication specialist, and a screenwriter with experience in the development of videos related to health topics. The research team, together with the producer, conducted the casting process and chose the actors (voices), images, music, and locations for the video.

For the development of the script, we considered the suggestions reported in the interviews with the target population: with basic and short messages, using simple and natural language and images, and with young actors with personalities that exist in real life. We also considered recommendations from related studies as well as the information about HPV from the World Health Organization, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the Secretariat of Health in Mexico. This allowed to improve the content of the messages of the video.

(V) Expert validation process

The fifth step was the validation of the contents of the first version of the video, which was carried out by 6 experts in sexual health topics as well as a focus group of 10 young people gathered in an online platform. The purpose was to obtain their general opinion and have the certainty that the information and messages were correctly understood. This allowed to determine the elimination and/or edition of a scene.

(VI) Pilot test

Finally, the sixth step was carrying out a pilot test with a group of 30 young people (since this video will be used for an internet intervention), who had access from a webpage in order to know their opinion about watching the video through this medium.

It is important to note that the information obtained from the interviews and the focus group was analyzed using data saturation sampling, where we identified emerging concepts and topics in order to create analysis categories and codes 20,21)). It is also important to clarify that this study was regulated by the principles of Bioethics and the General Health Law of Mexico, pertaining to its section on research with human beings, by obtaining the informed consent of all participants and having a registration number before a research committee (SIEP/033/2020).

RESULTS

(I) Descriptive literature review

The first stage of the study aimed to identify the main characteristics of the subject through a descriptive literature review. The result was a high lack of knowledge by young people about HPV, mainly in: not knowing the conditions that can generate the virus and a lack of information about the vaccine and detection tests 7,22. This situation can contribute to malpractice in their sexual health or having risky behaviors such as: having multiple sexual partners and not using a condom when having sexual contact. 4 This scientific evidence exposes the need to carry out interventions for HPV in order to inform, among other things, about prevention measures and risk factors 6.

With respect to the main educational tools used in prevention and the promotion of sexual health in the young population, we found that the use of audiovisual media, such as videos, that inform in a general way about aspects related to sexual health results effective for improving preventive behaviors for STIs 23.

(II) Analysis of interviews with the target population

In the second stage, we interviewed 10 young people between 18 and 23 years old; two were in upper secondary education, two were studying a degree in business administration, while the rest were studying degrees in gastronomy, law, nutrition, psychology, multimedia, and physics.

From the analysis of their responses, the following categories emerged regarding the knowledge and preferred characteristics to learn about HPV: 1.- Disinformation about: signs, symptoms, risk factors, and prevention, 2.- type of video, 3.- use of images, and 4.- style of characters.

For the first category, we found a clear lack of knowledge about signs, symptoms, risk factors, and prevention of HPV.

“…I don’t really know which are the signs and symptoms… I think it can be prevented with contraceptive methods (E3: 20 years)”; “it’s a disease that generally women have, but it attacks men more (E2: 21)”; “I wouldn’t know if someone developed symptoms, I have no idea about that… I don’t know if there are vaccines (E5: 19 years)”; “I don’t know if sexual relations influence getting HPV… I believe that one factor is not using contraceptives (E10: 23 years)”.

Regarding the type of video, the participants mainly preferred videos using clear, brief, and concrete information about HPV, with a duration time no longer than five minutes.

“A quick video… no longer than five minutes (E4: 18 years)”; “I prefer a video that is not boring or tedious, with clear, brief, and fundamental information (E6: 21 years); “A precise, brief, didactic video that is not full of letters (E8: 19 years)”.

For the use of images, they mostly preferred real and explicit images with the same style.

“I believe that a real image would make the concept more understandable (E7: 20 years)”; “I think that the images should be a little more explicit… to get an idea (E2: 23 years)”; “I believe it is more appealing when all the images have the same style (E7: 20 years)”.

Finally, for the style of the characters, they argued that they should be common people, inclusive (men and women), and contemporary. They also should not use a lot of medical language.

“…it should not have a lot of medical language, it should have common language …(E1: 18 years)”; “…it should be an appealing video, with a more contemporary style, not forced, should feel like being among friends, with real people …(E8: 18 years)”.

(III) Placing the information obtained within the components of the IMB model

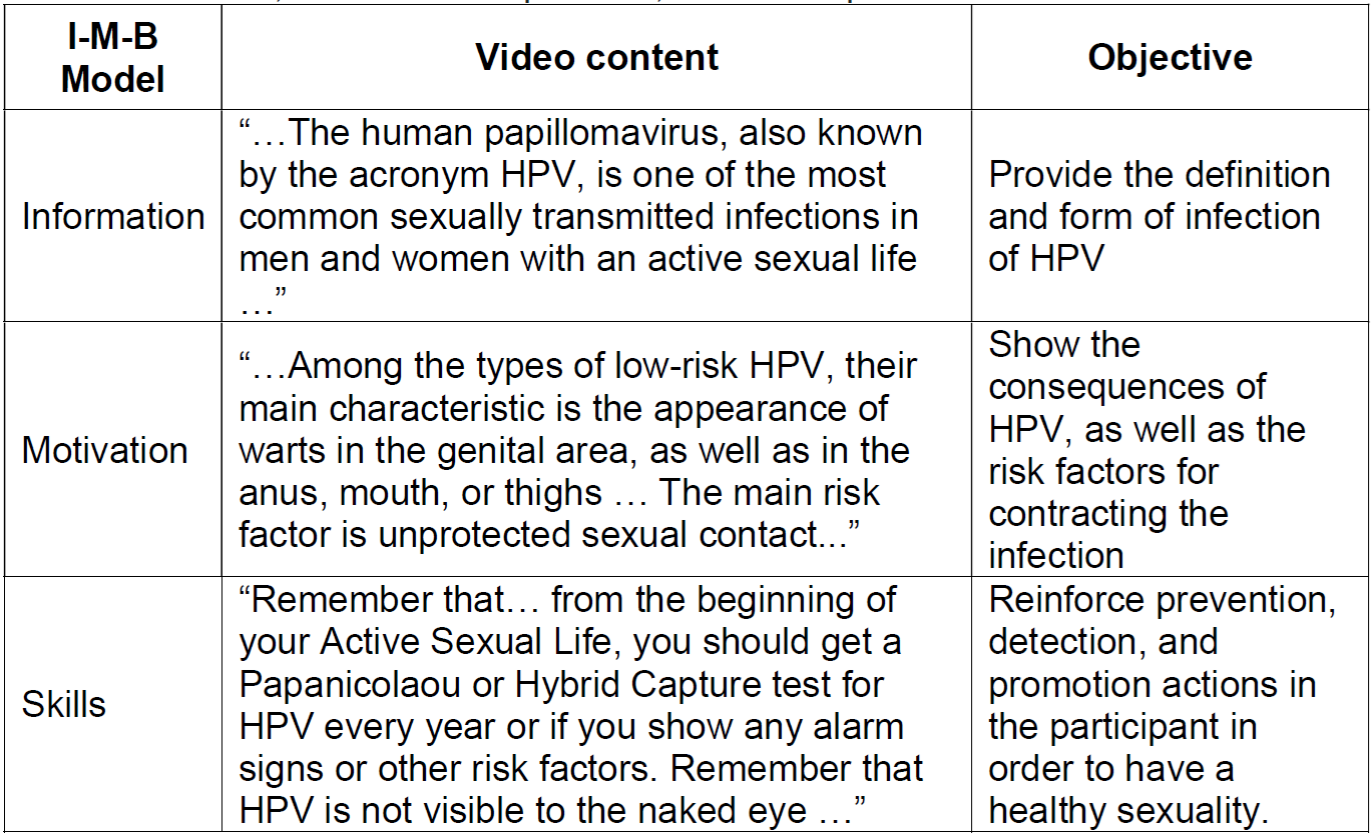

Once we obtained the information from the key participants and the scientific literature, we initiated the third step, which consisted in placing all the data within the components of the information-motivation-behavioral skills (IMB) model for the preliminary design of the video. For the first construct, we considered the knowledge about what is HPV and the ways to become infected. We placed signs and symptoms and risk factors within motivation. Finally, forms of prevention were placed within the skills construct (Table 1).

Table 1: Relationship between the information-motivation-behavioral skills (IMB) model, the video components, and the expected results.

Source: Author’s own construction.

(IV) Script development

Based on the above, for the fourth step, we decided, along with the multidisciplinary team, to design a video titled: “7 things that you should know about HPV!”, where two young people (a man and a woman) appear. The two people in the video answer, in a clear and simple way, seven questions about HPV, ending with a series of recommendations for preventing infection and promoting a responsible sexuality. The video was made using persuasive communication elements 24. This type of communication is characterized by trying to generate a positive change in the health behaviors of people through: 1.- an attractive font and characters similar to the recipient, 2.- an organization of clear and rational messages, 3.- a direct audio-visual communication channel, and 4.- a relaxed and pleasant context for the recipients. These aspects have allowed to change beliefs and inspire healthy sexual behaviors in previous studies 25,26.

(V) Expert validation process

Once the script was completed, we proceeded to the fifth step, which consisted in the validation of the content of the first version of the video by 6 experts in sexual health topics, as well as a focus group of 10 young people gathered in an online platform. For this, we calculated the content validity index (CVI) proposed by Rubio 27, where a value of 0.80 or higher indicates that the content of an instrument is adequate (Table 2).

Based on the above and with the suggestions from the focus group of young people, we decided to adjust the content on the definition and signs and symptoms of HPV. We also improved the writing of the sections corresponding to: ways of transmission, who should get vaccinated and when, and how it is diagnosed, obtaining a CVI= 0.92.

(VI) Pilot test

Finally, we conducted a pilot test with 30 young university students with the purpose of obtaining their opinion about the video. The young students rated the video as very good, understandable, and adequate in order to understand the basic aspects of HPV. They considered that the time was adequate and suggested to change the music to higher pitches in order to prevent the audience from getting distracted. They also suggested to change the place of some of the words that appeared in the video and enlarge some of the images in order to make a greater impact.

DISCUSSION

The present study aimed to describe the process of designing and validating an educational video for the prevention of HPV using the information-motivation-behavioral skills model.

During the review and analysis of the literature, we found a strong need for creating educational tools to increase the prevention knowledge of HPV. This also agreed with what has been reported in related studies about the lack of information about the signs, symptoms, risk factors, and ways of prevention found during interviews with the young population.

Furthermore, it can be observed, through the operationalization of the information-motivation-behavioral skills model in the components of the video, that this theoretical lens can be an effective tool for directing and explaining the processes of adopting preventive behaviors. This, together with persuasive communication techniques, could generate a significant effect on young people by promoting prevention and promotion strategies for a responsible sexuality through characters that use the same language and are of the same age. This allows the recipients to easily identify and assimilate the messages. This result agrees with that mentioned by Menacho and Blas 17, who refer to the importance of incorporating the target population into the intervention process, which consolidates their methodological proposal in the construction and design of educational videos for the promotion of sexual health.

Finally, it is important to consider that the preferences of young people change and are completely dynamic and constrained to the culture in which they live; added to this, is the fact that the scientific knowledge about the subject of HPV increases every year. All of this reveals an area of opportunity to continue reviewing, and where appropriate, updating the contents found in educational audiovisual tools (videos) with the purpose of making them relevant to young people.

CONCLUSIONS

The design and validation of a video for the prevention of HPV is a hermeneutical and systematic methodological process that promotes eclectic, heuristic, and innovative thinking for prevention and promotion of a responsible sexuality in the young population.

The content of the present study aims to be a reference for the construction of educational videos directed towards the promotion of health leaded by nursing professionals concerned with sexual health.

The present study contributes to promoting a continuous dialogue with the target population and the scientific literature, as well as a multidisciplinary and participatory approach that allows a better reflection in order to solve, in a creative and innovative way, the health needs of populations.

REFERENCIAS

1. Organización Panamericana de la Salud [Internet]. Acerca del VPH. El virus. [Obtenido: el 11 de agosto de 2020]. Disponible en: https://www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=14718:about-hpv-vaccine&Itemid=72405&lang=es#:~:text=La%20prevalencia%20del%20VPH%20en,en%20la%20regi%C3%B3n%20del%20perineo. [ Links ]

2. Organización Mundial de la Salud [Internet]. Acerca del VPH. Carga de la Enfermedad. [Obtenido el 10 de septiembre de 2020]. Disponible en: https://www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=14718:about-hpv-vaccine&Itemid=72405&lang=es#:~:text=La%20prevalencia%20del%20VPH%20en,en%20la%20regi%C3%B3n%20del%20perineo [ Links ]

3. Dirección General de Epidemiología [Internet]. Boletín Epidemiológico. Sistema Nacional de Vigilancia Epidemiológica. Sistema Único de Información. Semana 31. [obtenido el 11 de agosto de 2020]. Disponible en: https://www.gob.mx/salud/documentos/boletinepidemiologico-sistema-nacional-de-vigilancia-epidemiologica-sistema-unico-de-informacion-231750 [ Links ]

4. Contreras-González R, Magaly-Santana A, Jiménez-Torres E, Gallegos-Torres R, Xeque-Morales Á, Palomé-Vega G, et al. Nivel de conocimientos en adolescentes sobre el virus del papiloma humano. Enfermería Universitaria [Internet], 2017 [obtenido el 10 de septiembre de 2020]; 14 (2): 104-110. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.reu.2017.01.002 [ Links ]

5. Dönmez S, Öztürk R, Kisa S, Karaoz-Weller B, Zeyneloglu S. Knowledge and perception of female nursing students about human papillomavirus (HPV), cervical cancer, and attitudes toward HPV vaccination. Journal of American College Health, [Internet]. 2019 [obtenido el 10 de septiembre de 2020]; 67 (5): 410-417. Disponible en: DOI: 10.1080 / 07448481.2018.1484364 [ Links ]

6. Martínez-Martínez L, Cambra U. Conocimiento y actitudes hacia el virus del papiloma humano en una población de universitarios españoles= Knowledge and attitudes towards human papillomavirus in a population of Spanish university students. Revista española de comunicación en salud, [Internet] 2018 [obtenido el 10 de septiembre de 2020]; 9(1): 14-21. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.20318/recs.2018.4248 [ Links ]

7. Hernández-Márquez C, Brito-García I, Mendoza-Martínez M, Yunes-Díaz E, Hernández-Márquez E. Conocimiento y creencias de mujeres del estado de Morelos sobre el virus del papiloma humano. Rev. Cuba Enf. [Internet] 2016 [obtenido el 10 de septiembre de 2020]; 32(4):126-147. Disponible en: http://scielo.sld.cu/pdf/enf/v32n4/enf04416.pdf [ Links ]

8. Galbraith-Gyan K, Lechuga J, Jenerette C, Palmer M, Moore A, Hamilton J. African-American parents' and daughters' beliefs about HPV infection and the HPV vaccine. Public Health Nursing. [Internet] 2019 [obtenido el 10 de septiembre de 2020]; 36:134 - 143. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1111/phn.12565 [ Links ]

9. Pinheiro P, Miranda Cadete M. El conocimiento de los adolescentes escolarizados sobre el virus del papiloma humano: revisión integrativa. Enfermería Global, [Internet] 2019 [obtenido el 10 de septiembre de 2020]; (56): 603-623. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/eglobal.18.4.362881 [ Links ]

10. Barrios-Puerta Z, Díaz-Pérez A, Del Toro-Rubio M. Conocimientos acerca del Virus de Papiloma Humano y su relación con la práctica sexual en estudiantes de Ciencias de la Salud en Cartagena-Colombia. Ciencia y Salud Virtual. [Internet] 2016 [obtenido el 10 de septiembre de 2020]; 8(1): 20-28. Disponible en: https://revistas.curn.edu.co/index.php/cienciaysalud/article/view/670/530 [ Links ]

11. Soto-Zamalloa C. Relación entre el nivel de conocimiento y prácticas de prevención sobre el virus papiloma humano en gestantes atendidas en el Hospital San Juan de Lurigancho, 2018. [Internet] 2019 [obtenido el 10 de septiembre de 2020]; Disponible en: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12672/10433 [ Links ]

12. Von Sneidern E, Quijano L, Paredes M, Obando E. Estrategias educativas para la prevención de enfermedades de transmisión sexual en adolescentes. Revista Medica Sanitas. [Internet] 2016 [obtenido el 10 de septiembre de 2020]; 19 (4): 198-207. Disponible en: https://www.unisanitas.edu.co/Revista/61/RevTema_Estrategias_educativas.pdf [ Links ]

13. Al-Shaikh G, Syed S, Fayed A, Al-Shaikh R, Al-Mussaed E, Khan F, et al. Effectiveness of health education programme: Level of knowledge about prevention of cervical cancer among Saudi female healthcare students. Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association. 2017; 67 (4): 513-520. [ Links ]

14. Lemos M, Rothes A, Oliveira F, Soares L. Raising cervical cancer awareness: Analysing the incremental efficacy of Short Message Service. Health Education Journal. 2017; 76(8): 956-970. [ Links ]

15. Allen W. Increasing Knowledge of Preventing Sexually Transmitted Infections in Adult College Students through Video Education: An Evidenced-based Approach. ABNF Journal. 2017; 28(3): 64-68. [ Links ]

16. Fisher J, Fisher W. Changing AIDS-Risk Behavior. Psychological Bulletin, 1992; 3(3): 455-474. [ Links ]

17. Menacho L, Blas M. ¿Cómo producir un video para promover la prueba del VIH en hombres que tienen sexo con hombres? Rev. Perú Med Exp Salud Publica. 2015; 32 (3): 519-525. [ Links ]

18. Pérez G, Cruess D, Strauss M. A brief information-motivation-behavioral skills intervention to promote human papillomavirus vaccination among college-aged women. Psychol Res Behav Manag. [Internet] 2016 [obtenido el 10 de septiembre de 2020]; 9:285-296. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S112504 [ Links ]

19. Báez H, Márquez V, Onofre R, Benavides T, Flores M. Diseño de una intervención hacia la intensión y uso del condón en HSH. Sinapsis de la psicología en su profesionalización e investigación para la comunidad. Colegio de Psicología del Estado de Nuevo León. [Internet] 2018 [obtenido el 10 de septiembre de 2020]; 170-179. Disponible en: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325094777_Sinapsis_de_la_Psicologia_en_su_Profesionalizacion_e_Investigacion_para_la_Comunidad [ Links ]

20. Padgett D. Qualitative methods in social work research: challenges and rewards. 2nd ed. Los Ángeles, California: Sage Publications. 2008. [ Links ]

21. Glaser B, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago: Aldine Transaction. 1967. [ Links ]

22. Bendezu-Quispe G, Soriano-Moreno AN, Urrunaga-Pastor D, Venegas-Rodríguez G, Benites-Zapata VA. (2020). Asociación entre conocimientos acerca del cáncer de cuello uterino y realizarse una prueba de Papanicolaou en mujeres peruanas. Revista Peruana de Medicina Experimental y Salud Publica. [Internet] 2020 [obtenido el 10 de septiembre de 2020]; 37(1), 17-24. Disponible en: https://dx.doi.org/10.17843/rpmesp.2020.371.4730 [ Links ]

23. Nuramalia N, Maria IL, Jafar N. The Effectiveness of Audio-Visual Media Intervention Aku Bangga Aku Tahu (ABAT) toward Adolescent Attitude as a Practice of Prevention of HIV and AIDS Transmission. International Journal of Multicultural and Multireligious Understanding. 2019; 6 (5): 713-719. [ Links ]

24. Moya M. Persuasión y cambio de actitudes. En J. F. Morales (Ed.). Psicología social. Madrid: McGraw-Hill. 2000. [ Links ]

25. Bunn C, Kalinga C, Mtema O, Abdulla S, Dillip A, Lwanda J, et al. Arts-based approaches to promoting health in sub-Saharan Africa: a scoping review. BMJ Global Health. 2020; 5 (5): e001987. [ Links ]

26. Donné L, Hoeks J, Jansen C. Using a narrative to spark safer sex communication. Health education journal. [Internet] 2017 [obtenido el 10 de septiembre de 2020]; 76(6): 635-647. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1177/0017896917710967 [ Links ]

27. Rubio DM, Berg-Weber M, Tebb SS, Lee ES, Rauch S. Objectifying content validity: Conducting a content validity study in social work research. Social Work Research. 2003; 27(2), 94-104. [ Links ]

Received: September 24, 2020; Accepted: January 13, 2021

text in

text in