Meu SciELO

Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Enfermería Global

versão On-line ISSN 1695-6141

Enferm. glob. vol.21 no.66 Murcia Abr. 2022 Epub 02-Maio-2022

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/eglobal.482821

Originals

Psychometric properties of the modified conflict tactics scale. Application in the Ecuadorian adolescent context

1 Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador. Facultad de Enfermería. Grupo de Investigación prevención de la violencia de género (E-previo). Quito-Pichincha, Ecuador.

2 Escuela Universitaria de Enfermería de Cartagena. Departamento de Enfermería, Universidad de Murcia. España. marpastorbravo@um.es

The study of adolescent dating violence is relevant for Public Health, given its predictive nature and the social impact of this variable on the coexistence of the adult population. Dating violence rating scales need to be validated to ensure the reliability and certainty of their results.

Objective

To analyze the psychometric properties of the modified M-CTS conflict tactics scale in the context of dating violence among Ecuadorian adolescents.

Materials and methods

This is a validation study through confirmatory factor analysis and analysis of linguistic and cultural variables, with probabilistic sampling (n = 1249) with ages between 12-20 years, who met the requirements of having or having had a dating relationship.

Results

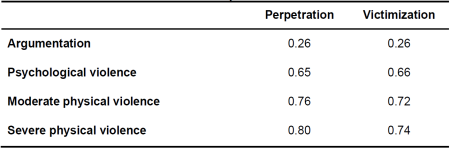

6 questions were culturally modified, and the 4-factor structure of the questionnaire was verified (argumentation, psychological violence, mild physical and severe physical). Low reliability was found for the perpetrator argument (0.26) and victimization (026) items and good reliability for severe physical violence for both profiles (0.80 and 0.76).

Main conclusions

The cultural adaptation of the M-CTS offered adequate validity for the diverse types of violence in the Ecuadorian adolescent population, allowing to compare the prevalence found in other countries that used this instrument based on the same theoretical and methodological perspectives.

Key words: Violence; intimate partner violence; cross-cultural adaptation

INTRODUCTION

In 1996, the 49th World Assembly of the World Health Organization declared violence a major public health problem worldwide, drawing attention to its grave consequences at the individual, family, and community levels. In this regard, it urged member countries to urgently address this issue through research, health care and by implementing preventive health programs and services1.

Dating violence has been defined as any attempt to exert control or dominance over a person, whether physical, sexual or psychological, resulting in some kind of harm to that person2. These aggressions can be strongly expressed in conflicted couples and can be sustained over time due to multiple reasons, including emotional immaturity, idealized expectations of love, and conservative beliefs about gender roles3.

However, although it is one of the main socio-health and educational problems that occur during adolescence4, the study of dating violence receives less attention than violence in adults and married couples5, where countless research studies have been conducted, prioritizing the abuser-abused model3,6-8. Despite its presence, many adolescents do not find violence in their dating relationships because they tend to misinterpret it as expressions of love or normal interactions9,10, which may increase in intensity, becoming reciprocal, addictive and pathological.

Assessment tools are useful not only for diagnosing the extent of a problem, but also for the subsequent implementation of preventive measures that are as specific and adapted to the population context as possible11. Hence the need for early detection of dating violence using reliable, culturally valid tools that facilitate its assessment and allow timely intervention with preventive programs and strategies for the empowerment and promotion of the integral health of those involved.

Scales are often used in violence studies on the assumption that there is cross-cultural invariance, and that the metrics are equivalent, without adequate validation in the context of the populations studied12. The Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS) and its later modified versions (M-CTS) have been the most widely used instruments for the assessment of dating violence12. This instrument is effective in the investigation of dating violence, both in those who perpetrate the aggression and in those who receive it. It has been used in the study of dating violence in high school students13,14 and university students15 among others.

This scale has been validated in the USA16. It has also been translated into Spanish and validated in Spain17. It has also been validated in Canadian and Italian populations18. A study has also been conducted in 2019 for its validation in Mexico12.

The study of dating violence in Latin America is on the rise19,20; however, it does not focus on using adapted instruments. Specifically in Ecuador, research was conducted to describe violence in dating relationships associated with sexist attitudes and distorted thinking19; the study found, among its results, a high level of hostile sexism, disguised as a false recognition of women, reinforcing the traditional feminine role and the justification of attitudes that imply violence among the young university students who took part in the study.

Although the M-CTS scale has been validated in a Spanish-speaking population, Ecuador has a great cultural diversity, which complicates the use of scales designed in other contexts for a population that is obviously different. Using scales without adequate adaptation may lead, at the risk of reaching conclusions that, instead of reflecting the problem, reflect deficiencies in the factor structure of the scale or measurement variables12.

For this reason, this study aims to evaluate the psychometric properties of the modified conflict tactics scale (M-CTS), as applied for the assessment of dating violence in the Ecuadorian context.

MATERIALS AND METHOD

Type of research

This was a non-experimental, quantitative, cross-sectional study whose design was aimed at evaluating the psychometric properties of the modified conflict tactics scale (M-CTS).

The psychometric properties of the M-CTS scale were analyzed in the study on dating violence in young Ecuadorians. A confirmatory factor analysis, a sequential and integrated treatment of the validity and reliability of each of the items of a scale, was applied21. Previously, a cultural review and adaptation process was carried out in order to strengthen the methodological rigor of the validation21.

Sampling

The study included a total of 1,249 high school students from public schools in Quito, Ecuador, mostly female (60%), aged 13-19 years (M = 15.64; SD = 1.58). Participants were classified by age in the ranges of middle adolescence (13-15 years) and late adolescence (16-19 years). Participants in this study reported having a partner at the time of the assessment or having had a partner previously. (Table 1). Those who had not previously had a partner were excluded from the study.

The research was conducted in private, public and public-religious institutions with General Basic Education (EGB) and High School levels in Quito canton. The levels are composed as follows: Upper Basic, which corresponds to 8th, 9th and 10th grades of EGB; then the Baccalaureate level, which comprises three years: 1st, 2nd, and 3rd year. The universe consisted of a total of 28,796 adolescents enrolled at that time at the Canton level; data were obtained from the National System of Educational Statistics (SINEC) available in the Master File of Educational Institutions (AMIE) for the period 2017-2018. For this study, 13 educational institutions, obtained from the AMIE 2017-2018 were randomly selected22.

Instruments

The Modified Conflict Tactics Scale (M-CTS) originally designed by Straus in 197923 and adapted to Spanish by Muñoz-Rivas, Andreu-Rodríguez, Graña-Gómez and O'Leary17 was applied. It consists of 18 Likert-scale items with five options, each with one version addressing aggression ("Have you thrown any object at your boyfriend/girlfriend?"), and one version addressing victimization ("Has your boyfriend/girlfriend thrown any object at you?"). In addition, an ad hoc questionnaire was used to collect sociodemographic data. Participants who said they had never had a boyfriend/girlfriend were excluded from the study.

Procedure

After obtaining the approval of the University’s Committee on Ethics and Research on Human Subjects (CEISH-PUCE), five experts, including a postdoctoral student with expertise in intimate partner violence, three nurses with more than 10 years of experience in research and scientific dissemination on the subject of violence, and a psychologist with expertise in the design of psychometric scales, reviewed the structure of the scale. The review was oriented to determine the writing clarity, internal coherence, response induction (bias), adequacy of language to the participants' level and relevance of each of the items in correspondence with the dimensions of argumentation, physical violence, psychological violence and sexual violence.

Subsequently, the voluntary participation of five young students between 18-21 years of age was requested to carry out the cultural validation of the scale. Here we considered the situations evoked or portrayed by the participants, based on the reading and interpretation of each item, in correspondence with the meaning given to them in the original culture of the instrument24. Then, the appropriateness of the language to the level of the participants was questioned and those words that did not adapt to the cultural context were replaced by terms appropriate to the participants' level.

The test technique was used, according to which, after reading each question, participants were asked to explain how they understood its meaning or how they understood what they were being asked. The researchers then identified words or phrases that, despite their general denotation, required modification or adaptation due to their cultural connotation in the Ecuadorian context.

Subsequently, the 5 experts compared the two versions of the instrument and verified the substitution of words, agreeing on the qualitative validity of the modified items. From the semantic point of view, the denotative and connotative correspondence of the words and phrases that made up each of the items was sought, so that, when applying the scale, their answers were not affected by any systematic effect, inherent to the questionnaire that would compromise the validity of the results21.

In this way, an attempt was made to facilitate the adolescents' understanding of the items during the data collection phase of the research. It must be taken into account that words do not always have the same connotation or are not always understood in the same way when applied in different cultural contexts25.

Statistical Analysis

Using the AMOS statistical program (SPSS, v. 25), the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) technique was applied to evaluate the factorial structure of the instrument. This technique allows us to determine whether the theoretical model fits the empirical data collected in the study17. Finally, reliability was calculated with Cronbach's alpha coefficient for the four dimensions, the aggression subscale and the victimization subscale. This calculation was performed by the researchers, with help from scholarship students registered in the project, who received prior training in applying the scale.

When applying the instruments, the young participants were reminded of the purpose of the research, the use that would be made of the data, and the researchers' commitment to the confidentiality of the data. Therefore, they were asked to answer sincerely and, if they had not had a girlfriend or boyfriend, to return the instrument to the person responsible for its application.

Ethical Aspects

The protocol for the development of the study was approved by the Committee on Ethics and Research in Human Subjects (CEISH-PUCE) code 2018-52-EO, validating all specific procedures involving the participation of human subjects. In this regard, the study complied with national regulations governing research involving human subjects and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. Furthermore, written permission was obtained from the principals of the educational institutions that participated in the research, as well as the informed consent of the adolescents of legal age and the consent of the parents or legal guardians of the minors and the assent of the underage participants.

RESULTS

Cultural and semantic adaptation of the scale

As a result of the meeting with the group of adolescents, words or phrases were found that were imprecise or doubtful to them, based on their cultural connotation, and that could interfere with the clarity of the items at the moment of their application to the sample of the study. Table 2 shows results of this analysis, as well as the restated items.

Confirmative Factorial Analysis

Because the data did not follow a multivariate normal distribution, the Bollen-Stine Bootstrapping Method, recommended for the treatment of data not following a normal distribution, was used26,27. To determine the goodness of fit of the model, the comparative fit index (CFI), goodness of fit index (GFI), adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI) and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) were used, according to the cut-off points proposed by Hu and Bentler28.

We studied the goodness of fit for the four-dimensional model reported in studies in Mexico12, Spain17 and the United States.29. Similarly, the two-dimensional model proposed by Cascardi, Avery-Leaf, O'Leary and Smith in 199914 was tested but discarded due to its inadequate fit indicators.

In the four-dimensional model, modifications were made in the correlations of error terms of items 1 and 2 (MI = 27.84 in aggression and MI = 33.46 in victimization), and of items 10 and 13 (MI = 48.46 in aggression and MI = 38.40), respectively, due to their high modification indexes and the content similarity of these items.16. Following these modifications, a good data fit was obtained in RMSEA, RMR and GFI, as well as acceptable AGFI and CFI indicators (see Table 3).

Group comparison

Scores were compared according to gender and age with the Mann-Whitney U test, given the non-normal distribution of the data. Men perpetrated higher levels of psychological violence, moderate physical violence, and severe physical violence. On the victimization scale, men reported higher levels of argumentativeness and women scored higher on psychological violence and moderate physical violence. However, the effect of gender on the different forms of perpetration and victimization was small.30) (see Table 4).

The 15-20 age group scored higher in the perpetration of argumentative, psychological, and moderate physical violence. It also showed higher levels in the argumentation and psychological violence dimensions of the victimization scale. Similarly, age had a small effect on the different forms of perpetration and victimization (see Table 5).

Reliability

Reliability measured according to Cronbach's Alpha ranged from α = 0.26 to 0.78 for the Argumentation and Serious Physical Aggression dimensions. According to previous research, the low reliability of the Argumentation dimension may be due to its small number of items.12.

DISCUSSION

This study focused on the validation of the M-CTS scale, previously adapted to Spanish17, when applied to the Ecuadorian adolescent population. M-CTS showed good psychometric properties for detecting dating violence in Ecuadorian adolescents; through factor analysis, items 1, 2, 10 and 13 were found to need modification. In order to determine the psychometric properties of the instrument, procedures similar to those applied in other studies were used to verify the reliability of the M-CTS when used in different contexts or realities12)(16)(17)(31.

Prior cultural adaptation was considered essential to strengthen the usefulness of inferential statistical processing; this leads to an increased need for methodological rigor in the process of adapting the analyzed questionnaires32. As well as to reduce systematic effects that might affect the questionnaire's validity and reliability22. This process identified items that were unclear or had a connotation different from the original one. That is, in agreement with previous research where some statements, and even some variables studied, had a different conceptualization for the young people participating in the studies12)(25)(29. The model found in this study was consistent with the theoretical proposal made by Straus23; the argumentation dimension needs to incorporate other questions for a better understanding or a new scale proposal due to the low reliability and low factor loadings obtained in contrast to the rest of the dimensions. Similarly, in the study that Muñoz-Rivas et al.17 carried out in Madrid, adapting M-CTS to Spanish, this was precisely the dimension where low levels of reliability were detected. This is why we encourage researchers to use the subscales instead of the total score.

The coercive model indicates that violence is less flexible and there is less dialogue, being more rigid in relationships and in violent communication in the family. Based on this premise, the evaluation of the argumentation or dialogue is of vital importance when selecting an instrument. Research concerning violence against women during relationships has recently increased, especially in at-risk populations such as adolescents; some authors suggest the need to review dating, no longer as a stage of little conflict, but as a period where often violent verbal, physical and sexual practices occur, widespread in the young population33, which can become a risk factor for more severe manifestations in the future13.

Dating violence behaves as a predictive dimension of half of the aggressions in married couples, being a key construct for the study and understanding of this phenomenon from a social approach34. In many cases, it can even be bidirectional9)(35)(36, with serious impacts on people's physical and psychological health13.

There is an increase in femicides. In Ecuador, there is a femicide every 72 hours; most of the victims are women between 25 and 39 years of age. These data show the importance of preventing dating violence at an early age, and the importance of using sensitive and reliable instruments.

There were some limitations in this study. First, there may be a memory bias; adolescent girls may not easily recall argumentative moments as opposed to violent moments. Second, there may be a self-selection bias; this means that participants in this study are more likely to be more attentive to bizarre or violent behavior in their partners. Third, we only investigate the individual's report and his/her own perception and the perception about his/her partner; this means that we do not have his/her partner's version to contrast information about who is a victim and who is an aggressor.

CONCLUSIONS

The factor analysis performed on the M-CTS, in its application to the context of Ecuadorian adolescents, confirmed the validity of measurement of this scale, as expressed in the strength of the relationship between the indicators assessed in the items and the corresponding constructs. The confirmatory perspective reported all the specific indicators correctly assigned to the specific dimensions of the variable, reinforcing the usefulness of the scale to study dating violence in this country.

In any case, it is necessary to incorporate other items to increase the reliability of the "argumentation" subscale, or to use a complementary scale to reliably measure this dimension. It is recommended to use other statistical procedures to verify differential functions of items, based on item response theory.

Performing a cultural adaptation will allow for a more realistic collection of information to reflect the problem. However, it is important to consider the low reliability of the argumentation section; therefore, we recommend the possibility of increasing items that complete the theoretical meaning of peaceful conflict resolution processes to improve its reliability.

Acknowledgments

Ministry of Education of Ecuador, teachers and adolescents from the educational institutions participating in the study

Financing:

Granted by the Pontifical Catholic University of Ecuador in the 2018 call for the project violence during dating: A mixed study in adolescents in Quito-Ecuador, under the funding code PI-044.

REFERENCES

1. Krug EG, Weltgesundheitsorganisation, editores. World report on violence and health. Geneva; 2002. 346 p. [ Links ]

2. Rey-Anacona CA. Maltrato de tipo físico, psicológico, emocional, sexual y económico en el noviazgo: un estudio exploratorio. Acta Colombiana de Psicología. 2009;12(2):27-36. Disponible en: http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/acp/v12n2/v12n2a03.pdf [ Links ]

3. De la Villa Moral M, García A, Cuetos G, et al. Violencia en el noviazgo, dependencia emocional y autoestima en adolescentes y jóvenes españoles. Revista Iberoamericana de Psicología y Salud. 2017;8(2):41. Disponible en: http://www.rips.cop.es/pii?pii=9 [ Links ]

4. Cala VC, Soriano-Ayala E. Cultural dimensions of immigrant teen dating violence: A qualitative metasynthesis. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2021; 58:101555. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2021.101555 [ Links ]

5. López-Cepero JL-C, Rodríguez Franco L, Rodríguez Díaz FJR, Bringas Molleda C. Violencia en el noviazgo: Revisión bibliográfica y bibliométricai. Psicothema. 2007;19(4):693-8. Disponible en: http://www.psicothema.es/pdf/3418.pdf [ Links ]

6. Muluneh MD, Alemu YW, Meazaw MW. Geographic variation and determinants of help seeking behaviour among married women subjected to intimate partner violence: evidence from national population survey. International Journal for Equity in Health. 2021;20 (1):13. doi: 10.1186/s12939-020-01355-5 [ Links ]

7. Leuenberger L, Lehman E, McCall-Hosenfeld J. Perceptions of firearms in a cohort of women exposed to intimate partner violence (IPV) in Central Pennsylvania. BMC Women's Health. 2021;21(1):20. doi: 10.1186/s12905-020-01134-y [ Links ]

8. Zukauskiene R, Kaniusonyte G, Bakaityte A, Truskauskaite-Kuneviciene I. Prevalence and Patterns of Intimate Partner Violence in a Nationally Representative Sample in Lithuania. J Fam Viol. 2021;36(2):117-30. doi: 10.1007/s10896-019-00126-3 [ Links ]

9. Pastor Bravo M. del M., Ballesteros Meseguer C., Seva Llor A. M., Pina-Roche F. (2018). Conocimientos, actitudes y prácticas de adolescentes españoles sobre la violencia de pareja. iQual. Revista de Género e Igualdad, (1), 145-158. doi: 10.6018/iQual.301161 [ Links ]

10. Del Moral G, Franco C, Cenizo M, Canestrari C, Suárez-Relinque C, Muzi M, et al. Myth Acceptance Regarding Male-To-Female Intimate Partner Violence amongst Spanish Adolescents and Emerging Adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(21):8145. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17218145. [ Links ]

11. Sanabria Vals, M. Diseño y validación de la escala: violencia en parejas adolescentes-victimización y perpetración (VPA-VP) para hispanohablantes. 2020. Universidad de Almería. Disponible en: http://repositorio.ual.es/handle/10835/10189 [ Links ]

12. Ronzón-Tirado RC, Muñoz-Rivas MJ, Zamarrón Cassinello MD, Redondo Rodríguez N. Cultural Adaptation of the Modified Version of the Conflicts Tactics Scale (M-CTS) in Mexican Adolescents. Front Psychol. 2019;10. Disponible en: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00619/full [ Links ]

13. Rubio-Garay F, López-González MA, Saúl LÁ, Sánchez-Elvira-Paniagua Á. Direccionalidad y expresión de la violencia en las relaciones de noviazgo de los jóvenes (Directionality and violence expression in dating relationships of young people. Acción Psicológica. 2012;9(1). Disponible en: http://revistas.uned.es/index.php/accionpsicologica/article/view/437 [ Links ]

14. Cascardi M, Avery-Leaf S, O'Leary KD, Slep AMS. Factor structure and convergent validity of the Conflict Tactics Scale in high school students. Psychological Assessment. 1999;11(4):546-55. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.11.4.546 [ Links ]

15. Rodríguez JA. Violencia en el noviazgo de estudiantes universitarios venezolanos. Archivos de Criminología, Seguridad Privada y Criminalística. 2014;(12):4-20. Disponible en: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=4714103 [ Links ]

16. O'Leary KD, Smith-Slep AM, Avery-Leaf S, Cascardi M. Gender differences in dating aggression among multiethnic high school students. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;42:473-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.09.012 [ Links ]

17. Muñoz-Rivas MJ, Andreu JM, Graña JL, O'Leary DK. Validación de la versión modificada de la Conflicts Tactics Scale (M-CTS) en población juvenil española. Psicothema. 2007;19(4):693-8. Disponible en: http://www.psicothema.es/pdf/3418.pdf [ Links ]

18. Nocentini A., Menesini E., Pastorelli C., Connolly J., Pepler D., Craig W. Physical Dating Aggression in Adolescence. Cultural and gender invariance. European Psychologist. 2011. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000045 [ Links ]

19. Boira S, Chilet-Rosell E, Jaramillo-Quiroz S, Reinoso J. Sexismo, pensamientos distorsionados y violencia en las relaciones de pareja en estudiantes universitarios de Ecuador de áreas relacionadas con el bienestar y la salud. Universitas Psychologica. 2017;16(4):1. Disponible en: http://revistas.javeriana.edu.co/index.php/revPsycho/article/view/14732 [ Links ]

20. Rojas-Solís J. L., Fuertes-Martin J. A., and Orgaz-Baz M. B. Dating violence in young Mexican couples: a dyadic analysis. Int. J. Soc. Psychol.2017. 32, 566-596. doi: 10.1080/02134748.2017.1352165 [ Links ]

21. Manuel Batista-Foguet J, Coenders G, Alonso J. Análisis factorial confirmatorio. Su utilidad en la validación de cuestionarios relacionados con la salud. Medicina Clínica. 2004;122(Supl.1):21-7. Disponible en: http://db.doyma.es/cgi-bin/wdbcgi.exe/doyma/mrevista.fulltext?pident=13057542 [ Links ]

22. MIE. AMIE (Estadísticas educativas a partir de 2009-2010) - Ministerio de Educación [Internet]. 2008 [citado 4 de junio de 2021]. Disponible en: https://educacion.gob.ec/amie/ [ Links ]

23. Straus MA. Measuring intrafamily conflict and aggression: The Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS). Journal of Marriage and The Family. 41(1):75-88. doi: 10.2307/351733 [ Links ]

24. Fiorin BH, Oliveira ERA de, Moreira RSL, Luna Filho B, Fiorin BH, Oliveira ERA de, et al. Adaptação transcultural do Myocardial Infarction Dimensional Assessment Scale (MIDAS) para a língua portuguesa brasileira. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva. 2018;23(3):785-93. Disponible en: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S1413-81232018000300785&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=pt [ Links ]

25. Guillemin F, Bombardier C, Beaton D. Cross-cultural adaptation of health-related quality of life measures: literature review and proposed guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46(12):1417-32. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90142-n [ Links ]

26. Kim H, Millsap R. Using the Bollen-Stine Bootstrapping Method for Evaluating Approximate Fit Idices. 2014. Multivariate Behav Res. 49(6):581-96. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4280787/ [ Links ]

27. Blunch NJ. Introduction to Structural Equation Modeling using IBM SPSS Statistics and AMOS. 1 Oliver's Yard, 55 City Road London EC1Y 1SP: SAGE Publications, Ltd; 2013. Disponible en: http://methods.sagepub.com/book/introduction-to-structural-equation-modeling-using-ibm-spss-statistics-and-amos [ Links ]

28. Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6(1):1-55. Disponible en: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10705519909540118 [ Links ]

29. Straus MA. Cross-Cultural Reliability and Validity of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scales: A Study of University Student Dating Couples in 17 Nations. Cross-Cultural Research. 2004;38(4):407-32. Disponible en: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1069397104269543 [ Links ]

30. Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2a ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [ Links ]

31. Graña JL, Andreu JM, de la Peña ME, Rodríguez MJ. Validez factorial y fiabilidad de la "Escala de tácticas para el conflicto revisada" (Revised Conflict Tactics Scales, CTS2) en población adulta española. Revista internacional de psicología clínica y de la salud. 2013;21(3):525-44. [ Links ]

32. Gjersing L, Caplehorn JR, Clausen T. Cross-cultural adaptation of research instruments: language, setting, time and statistical considerations. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010, 10:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-10-13. [ Links ]

33. Delgado JB. Violencia en el Noviazgo: Diferencias de Género. Informes Psicológicos. 2016;16(2):27-36. Disponible en: https://revistas.upb.edu.co/index.php/informespsicologicos/article/view/6845 [ Links ]

34. Peña-Cárdenas F, Zamorano-González B, Hernández-Rodríguez G, Hernández-González M de la L, Vargas-Martínez JI, Parra-Sierra V. Violencia en el noviazgo en una muestra de jóvenes mexicanos. Revista Costarricense de Psicología. 2013;32(1):27-40. Disponible en: http://www.rcps-cr.org/openjournal/index.php/RCPs/article/view/17 [ Links ]

35. Medina-Maldonado V, Pastor-Bravo M, Vargas E, Francisco J, Ruiz IJ. Adolescent Dating Violence: Results of a Mixed Study in Quito, Ecuador. J Interpers Violence. 2021; 25. doi:10.1177/08862605211001471 [ Links ]

36. Straus MA. Dominance and symmetry in partner violence by male and female university students in 32 nations. Children and Youth Services Review. 20;30(3):252-75. Disponible en: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0190740907001855 [ Links ]

Received: June 08, 2021; Accepted: November 17, 2021

texto em

texto em