My SciELO

Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Enfermería Global

On-line version ISSN 1695-6141

Enferm. glob. vol.21 n.68 Murcia Oct. 2022 Epub Nov 28, 2022

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/eglobal.512191

Originals

Identification of the needs of informal caregivers: an exploratory study

1Research group on Methodology, Methods, Models and Outcomes of Health and Social Sciences (M3O). Faculty of Health Sciences and Welfare. Centre for Health and Social Care Research (CESS).University of Vic-Central University of Catalonia (UVIC-UCC), Vic, Barcelona, Spain

2Santa Cruz University Hospital, Vic, Barcelona, Spain

3Faculty of Nursing, University of Girona, Girona, Spain

4Research Unit in Health Care and Services of the Carlos III Health Institute (Investén-isciii), Madrid, Spain

Introduction:

Population aging is one of the main issues in public health within developed countries. Informal caregivers play a central role in this scenario, which can affect them negatively.

Objective:

The aim of this study is to identify the needs of informal caregivers related to the care of dependent persons of a Basic Health Area.

Method

Qualitative and phenomenological study. Four informal caregivers in charge of non-institutionalized patients took part. These patients expressed their opinions in a semi-structured interview, that was deductively analyzed afterwards.

Results:

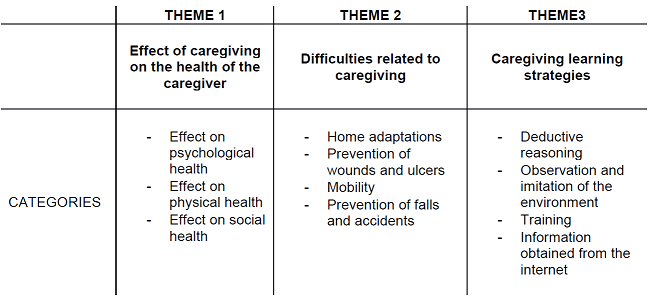

The analysis showed three key subjects: the effects of caregiving (how this task negatively affects the global health of the caregivers); difficulties related to care (related to the process of adaptation once at home, prevention of wounds, accidents and mobility issues), and caregiving learning strategies (by deductive reasoning, observation and formation).

Conclusions:

Caregiving has a negative effect on the caregivers' global health. They show some difficulties in the execution of their tasks, and they declare that they are using various caregiving learning methods. Interventions directed at informal caregivers should include aspects related to health improvement and caregiving training.

Key words: Informal caregiver; care needs; qualitative investigation

INTRODUCTION

The increase in life expectancy, improvements in public health and health care, as well as the adoption of certain lifestyles, have determined a greater aging of the population in Spain. Currently, life expectancy is 82.34 years old, and the country ranks fifth in life expectancy in the European Union, below Sweden, Italy, Malta and Ireland1. This aging of the population, however, results in a decrease in the functional capacity of people and in an increase in chronic processes2,3.

It is estimated that by 2050 there will be 1.5 billion people over the age of 60 in the world. Approximately 45% of people pertaining to this group will have a disability, and between 20% and 33% will require external assistance or care4,5. In addition, aging entails a limitation in the quality of life of the affected people and is associated with a high demand for gerontological care, as well as having an economic impact on families, communities and society. Therefore, population aging currently constitutes one of the main public health challenges in developed countries6.The care model in Spain is mainly focused on the family environment and frequently in the person's home, with relatives assuming the task of caregiving7.

Consequently, the figure of the informal caregiver acquires great importance today in the context of caregiving. The concept of informal care has been used to refer to a type of support system developed by people in the social sphere of the recipient of care, and it is provided voluntarily, without any organization or remuneration. In informal care, three categories of support are usually distinguished: material or instrumental support, informational or strategic support, and emotional support. Studies indicate that 88% of care falls on a family caregiver and only 12% is assumed by the healthcare system(3). According to Rogero8, men who live in households with fewer socioeconomic resources are more likely to receive informal care. Caregiving can be a source of satisfaction, but it can also can cause stress and emotional tension. When informal caregivers feel that the care provided is insufficient, it can lead to feelings of exhaustion, depression and guilt9.

Previous studies have shown that caregivers are 25-50% more likely to suffer from anxiety and/or depression2,6. Sleep-related problems have also been described more frequently among caregivers3,10. Additionally, caregivers often encounter difficulties in their social and relational spheres, especially when the care recipient has cognitive issues11. Caregivers are often isolated from their friends, relatives and work environment12.

Consequently, Ortiz13 proposed the concept of caregiver overburden as the total physical, psychological, emotional and financial cost of providing care for a person. This overload affects their capacities as caregivers, which in turn has an effect on the survival of patients13.

According to Ortiz(13), it is essential that family caregivers know the basic aspects of caregiving. In this sense, there is currently evidence on the effectiveness of some nursing interventions to reduce the burden of informal caregivers. The educational program "Caring for caregivers" ("Cuidando a los cuidadores" in the original in Spanish), aimed at improving the knowledge and skills of caregivers about their own work, would be an example of this14.

Identifying the needs of caregivers is essential to minimizing their burden and stress when providing care15. However, the perception of health professionals about these needs is insufficient, since it often differs from the opinion of caregivers15.

The aim of this study is to identify the needs of informal caregivers related to the care of a dependent person in a Basic Health Area.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study design

Qualitative and phenomenological approach study based on Judith Green & Nicki Thorogood (2018)16. Qualitative methodology offers the possibility of understanding the complexity of a phenomenon from the different points of view of the informants17.

Study area and participants

The study was carried out in the field of primary care, in a Basic Health Area of the Girona health region, which provides care to a total population of 32,600 people.

The participants of this study are informal caregivers of dependent people in this area.

Recruitment of participants and data collection

The selection of the participants was conducted from an intentional sampling16. The selection criteria that were taken into account were: age, gender, family relationship with the dependent person, care time, residence in the same home and whether they shared caregiving responsibilities with other caregivers. Primary care nurses proposed possible candidates within the basic health zone. Following the selection criteria, 4 profiles were finally obtained, which were the most representative within the caregiver profile in the area.

Sociodemographic data of the participants was collected to characterize the sample. The level of dependency (Barthel index(18)) and the level of frailty (Frailty Index Frail-VIG(19)) of the care recipients were also measured (Table 1).

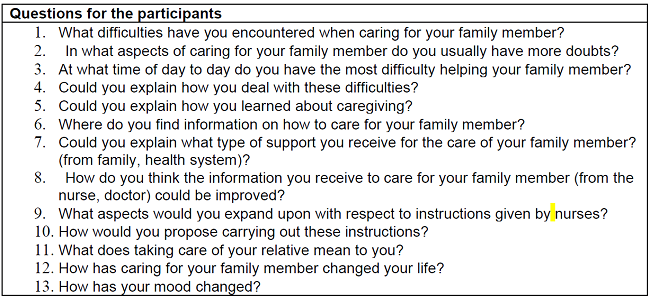

Primary care nurses initiated contact with the participants, who had no previous relationship with the principal investigator. The nurses accompanied the main researcher to the home of each participant to carry out individual semi-structured interviews. The interviews lasted between 45-60 minutes, approximately. Prior to the start of the interviews, a questionnaire based on the study by McCann(20) (Table 2) was prepared.

The interviews were recorded with the prior authorization from the caregiver by signing the informed consent document, and at the end of each interview the interviewer recorded her notes.

During the transcription, all data related to the interviewees was anonymized. In addition, a copy of the transcript was given to each of the corresponding participants to obtain their approval before data analysis started.

Data Analysis

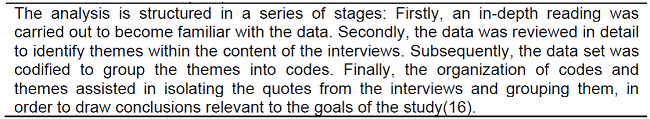

A deductive discourse analysis of the transcripts was performed based on the Green and Thorogood proposal(16). This qualitative analysis is characterized by the development of a conceptual map containing all the content and the creation of themes for the data set of the same topic(Table 3). The analysis was carried out in parallel by two independent researchers, after which the marked codes were pooled. When a discrepancy was found in both analysis, the data was reviewed together to reach an agreement. Atlas Ti 8.0 software was used as computer support for the discourse analysis.

Reflexivity

The principal researcher is an experienced home health care nurse with knowledge in the field. The second researcher is a physiotherapist with experience in home health care and qualitative analysis. The remainder researchers are nurses with extensive experience both in the professional and academic fields.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee CEIC Hospital Universitari de Girona Doctor Josep Trueta Girona. The participants were informed about the purpose of the study, and their written consent was requested. During the course of the research, the confidentiality and anonymity of the participants were maintained, adhering to the bio-ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki21. In order to ensure the quality of the study, criteria of rigor and ethical criteria of qualitative research were taken into account22. The data obtained was stored and protected, complying with the regulations of Organic Law 3/2018, December 5, on the Protection of Personal Data and guarantee of digital rights.

RESULTS

The study sample consisted of four caregivers, with a mean age of 63.75 years (9.95). Women made up 50% of the participants. Considering the degree of kinship of the caregivers, 50% of them are daughters, 25% are the partner (husband) and the other 25% are a friend. The participating caregivers had been providing care for an average of 9 years, 75% of the caregivers lived with the patient 24 hours a day in the same home and 100% of the sample assumed the role of caregiver without any additional support.

In relation to the care recipients, 75% presented a total dependence to perform daily activities, and 50% of the sample had an advanced degree of frailty (Table 1).

The analysis of the content of the participants' interviews identified three themes: the effect of care giving on the physical, emotional and social health of the caregiver; care-related difficulties; and caregiver's knowledge about caregiving. Table 4 shows the themes and categories identified after the interviews were analyzed.

1. Effects of care-giving on the health of the caregiver

Caregivers experience various negative feelings and emotions when providing care for a family member. The participants express feelings of fear, anguish and concern about their ability to provide care. These emotions also surface when the caregiver is obliged to leave their recipient of care home alone.

“So many times I worry when I leave her alone at home. I shut everything for her and I go back home, but sometimes I have to go back to her house, just to reassure myself…” [C2]

“Sometimes I think that I spend too much time away (when grocery shopping) and I come home quickly to be with her again…” [C4]

"For a while she would take off her diaper every night, nobody told us what we could do about it and it worried us..." [C4]

One of the participants added that he sometimes feels undervalued and unappreciated by the person he cares for, and that this feeling negatively affects his emotional state.

“Patients become selfish, since it is their illness, but it is difficult to get used to being despised and undervalued. Sometimes he lashes out at me…” [C3]

These negative feelings have a direct effect on the psychological health of the participants, who all agree on the mental exhaustion involved in caring for a dependent family member. Similarly, some caregivers stated feeling weak, unable to cope, and in those moments they have wondered if the choice to care for their family member was the right one.

"I don't know how I didn't get depressed, there were times when I felt very weak and with little desire to do anything..." [C4]

The participants stated that caring for a patient is a complicated process, with a direct impact on their physical health. A majority of caregivers reported feeling physically exhausted. Likewise, all the participants agreed that caring for a person has a negative effect on their self-care.

“…I have four vertebrae tied with titanium from a traffic accident… when I have to stand like this (referring to their body posture when washing the patient), with the sponge to wash him, there are times when my back hurts a lot…” [C3]

"There are times when I need to go out and I can't, and I would like to go out, go for a walk, but... no, I can't leave her alone..." [C1]

The participants agreed on the impact of caregiving on their relationships with partners and in their social relationships. Some stated that caregiving involves a lack of intimacy which prevents them spending time with their partners. Other participants state that they have changed the dynamics of family gatherings so that the dependent relative is not disturbed.

"We don't have intimacy now (my partner and I), we can't talk privately or do our own thing.." [C4]

"We only invite the grandchildren on specific days, because when they are there (at the patient's home) they run, jump, scream, and she (referring to the patient) can't stand it and we get nervous..." [C4]

At this point, the participants expose the negative consequences of being a caregiver in family and social relationships. However, they acknowledge that they often reject help from other people, on the basis that nobody will be able to provide care as well as them. This fear leads caregivers to not delegate care, thus isolating themselves from social relationships as well as preventing them from performing other roles due to having to assume the role of caregiver.

“One day we went to a party with friends and the son came to take care of the grandmother (referring to the dependent person). When we got back she was very nervous and that night we had a really bad time…” [C4]

Finally, and in relation to the global health of the caregivers, they stated that family was a great support against becoming overwhelmed. One caregiver added that friends help them unwind.

“My sister, the one who can make it, comes every three months and stays for about a month or four or five weeks. I am then more rested, I feel calmer…” [C2]

2. Difficulties related to care giving

During the analysis of the interviews, it was detected that the participants presented several difficulties when it came to caregiving, related to adaptations at home, the prevention of wounds and ulcers, and mobility issues.

In relation to home adaptations, the majority of the participants stated that they initially had a clear understanding of them.

Among the most common adaptations made by caregivers is bathroom accessibility, i.e. installing a shower. The removal of furniture and rugs, as well as having a light with a motion sensor to reduce the risk of family members falling were also mentioned.

Installing a platform lift was also identified as a frequent home adaptation.

“When she came home I had already adapted everything, I had put a stair-lift, I removed the bathtub and put a shower pan, I got a trolley to help her to the shower…” [C1].

Participants reported, however, that over time more adaptations would be necessary, and admitted difficulty in recognizing which ones would suit the needs of their dependent family member. Caregivers recounted having made adaptations based on accidents their relatives suffered, showing concern for their failing to anticipate these needs due to a lack of knowledge or information.

“We have been adapting everything, one day she fell and rolled under the bed, we had to put a railing…” [C4]

"She got up at night and as she had moved some piece of furniture she bumped into it and fell... we have put up a motion sensor light in case she gets up at night..." [C2]

In a similar vein, the caregivers claimed insufficient information regarding some activities relating to caregiving. For instance, they complained about a lack of training in dealing with wounds caused by wet diapers. At this point, two participants expressed that attending training aimed at caregivers could prove useful, to increase their knowledge about care iving and thus be able to anticipate possible problems. Caregivers feel that training is key to being able to offer quality care to their relatives.

“…a wound appeared. If I had known that the redness was dangerous, I would have acted accordingly…” [C3]

“When you have the knowledge, care is infinitely better…” [C3]

“The state of the dependent is not fixed, it is getting worse, it never gets better, one day you need 1 and the next day you need 1.5. There is a deterioration. Therefore, the caregiver has to adapt to new situations. If it doesn't catch you by surprise, if someone explains it to you and teaches you to care for those needs, it's much better…” [C3]

“I find that there is not enough information on caring for a dependent person…” [C1]

One of the participants expressed concern on the lack of training in regards to mobility aid for his family member. The caregiver stated that effective training from a physiotherapist would be beneficial.

"...I would need a physiotherapist to teach me some exercises so that she could do them (referring to the dependent person), I do what I can..." [C2]

The participants also expressed difficulties related to the prevention of falls and home accidents, especially those derived from dangerous materials or utensils such as bleach, scissors and knives.

"...One day we found the sofa in pieces, she (referring to the dependent person) had taken a pair of scissors and destroyed it... I also had to take the knives away because she wanted to slash a painting..." [C2]

3. Caregiving learning strategies

The participants stated that they had learned about caregiving from deductive reasoning, without external aid. Therefore, we found that the caregivers were mainly self-taught and that they would find solutions and strategies to care for the family member based on their own experiences.

“I have been learning little by little, nobody taught me…” [C4]

“It's like learning a trade over time. We have learned a trade, that of caring…” [C4]

At the same time, they mentioned that observing and imitating other people performing care tasks, such as health professionals or other caregivers, helps them in their learning process. Sharing knowledge with other people, friends and family who are in similar situations has also proven helpful.

“I would observe (a nurse, a caregiver, working) and well, little by little, you learn how to move her, how to shower her…” [C1]

"I meet people who have relatives in the same situation and we exchange opinions... that helps me..." [C2]

One of the caregivers mentioned caregiving training to be beneficial in learning how to care for a dependent relative. Specifically, this caregiver had completed training that taught useful techniques for the daily care of his family member.

"I learned quite a lot in the course, it helped me..." [C3]

The caregivers stated that to quickly solve problems related to the care of their family member, they would frequently search for information on the Internet. However, they expressed that often the information they found would not meet their needs.

“Well, from what I have been able to find on the internet, and what the nurses have told me, I have been adapting to his needs… [C3]

“…there is a lot of information that I need, such as how to bathe her, that can't be found on the internet. I manage as well as I can…” [C1]

DISCUSSION

The main themes that have emerged from the analysis are: the effect of caregiving on the health of caregivers, the difficulties related to caregiving and learning strategies from caregivers.

The results of this study show that caregivers experience negative feelings and emotions when caring for their relatives. In this sense, previous studies have identified greater feelings: anger, frustration, sadness and despair among caregivers of dependent people23. According to Wells, caring for a person increases the rate of depression and anxiety by four24, and these negative feelings and emotions are associated with a more aggressive way of providing care25. Likewise, the caregivers interviewed stated that they suffered from stress due to caregiving, which led to mental and physical exhaustion.

Previous studies have also shown negative effects on the mental and physical health of caregivers24,25. According to the WHO, health should be measured from a physical, mental and social perspective26. Taking this into consideration, the participants reported negative effects from caregiving in their social relationships, which directly affects this facet of health. According to Tay, family members are sometimes forced to assume the role of primary caregiver, negatively impacting their social health25.

This phenomenon is described in the literature as devotion, the total commitment that the caregiver has towards the person receiving care. This feeling prevents the caregiver to from considering other care alternatives23. Other research demonstrates the negative repercussions on an individual's work and family environment that result from taking on the role of caregiver to a relative23. However, caregivers seek coping strategies to reduce negative thoughts and the emotional burden, such as seeking social support and distractions24. Following on this research, the results of this study showed that caregivers seek support above all from family members.

The participants also mentioned difficulties with home adaptations related to caregiving, especially with regard to bathrooms. Several studies state that caregivers make physical changes at home in order to increase safety and reduce falls or potential accidents27. These home modifications typically include: removal of rugs, removal of hazardous items from the kitchen, adding lighting fixtures and automatic night lights27.

The participants claimed home adaptations become increasingly difficult in more advanced phases of caregiving. Some studies highlight the importance of professional support regarding home modifications. These professionals help caregivers adapt home modifications as the patient's deterioration progresses. These professionals add that any limitation from caregivers in regards to home adaptations is due to insufficient training27.

Following along these lines, caregivers face practical problems due to inadequate knowledge, and highlight the importance of interventions directed at them, after which caregivers feel more knowledgeable, more competent and confident when it comes to caring for the elderly27.

According to Kizza28, caregivers currently find themselves facing difficulties resulting from insufficient knowledge. In this sense, the results of our study show that caregivers' ways of learning are from deductive reasoning, by imitation of other people's experiences, and through training courses.

Caregivers added that sometimes they would search for information on the Internet, but the results did not meet their needs. In a similar vein, the literature confirms concerns about the quality and ability to discern the validity of the information gathered from the internet29. However, several investigations support that new technologies are a good tool to provide information and support to caregivers30.

This research presents some limitations that must be taken into account. Firstly, four semi-structured interviews were carried out in which the main researcher perceived a repetition of themes during the course of the interviews. As it is an intentional sample, where the researchers sought maximum representativeness within the specific study population, it is considered that data saturation was achieved with this sample. Secondly, the sample was recruited from a single Basic Health Area due to the available resources for this research. This fact could influence the results to be considered unrepresentative of the general population.

CONCLUSION

Caregiving has a negative impact on the physical, psychological and social health of informal caregivers. This group faces difficulties with home adaptations, wounds and fall prevention as well as mobility issues. Finally, informal caregivers learn about caregiving from deductive reasoning, by imitation and with training. In this sense, all interventions aimed at informal caregivers should include aspects related to the betterment of their health and training in caregiving.

REFERENCIAS

1. Expansión. Esperanza de vida al nacer [Internet]. Available from: https://datosmacro.expansion.com/demografia/esperanza-vida [ Links ]

2. Frías-Osuna A, Moreno-Cámara S, Moral-Fernández L, Palomino-Moral PÁ, López-Martínez C, del-Pino-Casado R. [Motives and perceptions of family care for dependent elderly]. Aten primaria [Internet]. 2019 Dec 1 [cited 2022 Feb 22];51(10):637-44. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30424899/ [ Links ]

3. Moral-Fernández L, Frías-Osuna A, Moreno-Cámara S, Palomino-Moral PA, del-Pino-Casado R. Primeros momentos del cuidado: el proceso de convertirse en cuidador de un familiar mayor dependiente. Atención Primaria [Internet]. 2018 May 1 [cited 2022 Feb 22];50(5):282-90. Available from: https://www.elsevier.es/es-revista-atencion-primaria-27-articulo-primeros-momentos-del-cuidado-el-S0212656717302202 [ Links ]

4. Akgun-Citak E, Attepe-Ozden S, Vaskelyte A, van Bruchem-Visser RL, Pompili S, Kav S, et al. Challenges and needs of informal caregivers in elderly care: Qualitative research in four European countries, the TRACE project. Arch Gerontol Geriatr [Internet]. 2020 Mar 1 [cited 2022 Feb 22];87:103971. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31756568/ [ Links ]

5. Palacios-Ceña D, León-Pérez E, Martínez-Piedrola RM, Cachón-Pérez JM, Parás-Bravo P, Velarde-García JF. Female family caregivers' experiences during nursing home admission: A phenomenological qualitative study. J Gerontol Nurs [Internet]. 2019 Jun 1 [cited 2022 Feb 22];45(6):33-43. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31135935/ [ Links ]

6. Wool E, Shotwell JL, Slaboda J, Kozikowski A, Smith KL, Abrashkin K, et al. A Qualitative Investigation of the Impact of Home-Based Primary Care on Family Caregivers. J frailty aging [Internet]. 2019;8(4):210-4. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31637408/ [ Links ]

7. Organización Panamericana de la Salud, Organización Mundial de la Salud. Estrategia para la prevención y el control de las Enfermedades no Transmisibles, 2012-2025. 28° Conf Sanit Panam [Internet]. 2012;1:1-14. Available from: http://www1.paho.org/spanish/gov/csp/csp27.r10-s.pdf [ Links ]

8. Rogero-García J. Distribución en España del cuidado formal e informal a las personas de 65 y más años en situación de dependencia [Internet]. Revista Española de Salud Pública. 2009 [cited 2022 Feb 22]. Available from: https://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1135-57272009000300005 [ Links ]

9. Madsen R, Birkelund R. 'The path through the unknown': the experience of being a relative of a dementia-suffering spouse or parent. J Clin Nurs [Internet]. 2013 Nov 1 [cited 2022 Feb 22];22(21-22):3024-31. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/jocn.12131 [ Links ]

10. Liu S, Li C, Shi Z, Wang X, Zhou Y, Liu S, et al. Caregiver burden and prevalence of depression, anxiety and sleep disturbances in Alzheimer's disease caregivers in China. J Clin Nurs [Internet]. 2017 May 1 [cited 2022 Feb 22];26(9-10):1291-300. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27681477/ [ Links ]

11. Harris PB. Dementia and friendship: the quality and nature of the relationships that remain. Int J Aging Hum Dev [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2022 Feb 22];76(2):141-64. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23687798/ [ Links ]

12. Moral-Fernández L, Frías-Osuna A, Moreno-Cámara S, Palomino-Moral PA, Del-Pino-Casado R. The start of caring for an elderly dependent family member: a qualitative metasynthesis. BMC Geriatr [Internet]. 2018 Sep 25 [cited 2022 Feb 22];18(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30253750/ [ Links ]

13. Ortiz Claro, Yirle Grecia; Lindarte Clavijo, Albeiro Antonio; Jimenz Sepulveda, Mónica Angely and Vega Angarita OM. Características sociodemográficas asociadas a la sobrecarga de los cuidadores de pacientes diabéticos en cúcuta [Internet]. Revista Cuidarte. 2013 [cited 2022 Feb 22]. p. 459-66. Available from: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?pid=S2216-09732013000100005&script=sci_abstract&tlng=es [ Links ]

14. Chaparro Díaz OL, Carrillo González GM, Sánchez Herrera B. La carga del cuidado en la enfermedad crónica en la díada cuidador familiar-receptor del cuidado. Investig en Enfermería Imagen y Desarro [Internet]. 2016;18(2):43. Available from: https://revistas.javeriana.edu.co/index.php/imagenydesarrollo/article/view/12136 [ Links ]

15. Jennings LA, Reuben DB, Evertson LC, Serrano KS, Ercoli L, Grill J, et al. Unmet needs of caregivers of individuals referred to a dementia care program. J Am Geriatr Soc [Internet]. 2015 Feb 1 [cited 2022 Feb 22];63(2):282-9. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25688604/ [ Links ]

16. Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative methods for health research. 4ta edició. London: Sage Publications; 2018. [ Links ]

17. Taylor, S.J.; Bogdan, R.; De Vault M. Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods: A Guidebook and Resource. 4th ed. Wiley Publications, editor. USA: Wiley Publications; 2015. [ Links ]

18. Bernaola-Sagardui I. Validation of the Barthel Index in the Spanish population. Enfermería Clínica (English Ed [Internet]. 2018 May 1 [cited 2022 Feb 22];28(3):210-1. Available from: /https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29397315/ [ Links ]

19. Amblàs-Novellas J, Martori JC, Espaulella J, Oller R, Molist-Brunet N, Inzitari M, et al. Frail-VIG index: a concise frailty evaluation tool for rapid geriatric assessment. BMC Geriatr [Internet]. 2018 Jan 26 [cited 2022 Feb 22];18(1). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5787254/ [ Links ]

20. Mccann T V., Bamberg J, Mccann F. Family carers' experience of caring for an older parent with severe and persistent mental illness. Int J Ment Health Nurs [Internet]. 2015 Jun 1 [cited 2022 Feb 22];24(3):203-12. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25963281/ [ Links ]

21. Asociación Médica Mundial. Declaración de Helsinki de la AMM - Principios éticos para las investigaciones médicas en seres humanos - WMA - The World Medical Association [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2020 Feb 27]. Available from: https://www.wma.net/es/policies-post/declaracion-de-helsinki-de-la-amm-principios-eticos-para-las-investigaciones-medicas-en-seres-humanos/ [ Links ]

22. Noreña AL, Alcaraz-Moreno N, Rojas JG, Rebolledo-Malpica D. Aplicabilidad de los criterios de rigor y éticos en la investigación cualitativa. Aquichan [Internet]. 2012;12(3):263-74. Available from: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?pid=S1657-59972012000300006&script=sci_abstract&tlng=es [ Links ]

23. Caputo A. The emotional experience of caregiving in dementia: Feelings of guilt and ambivalence underlying narratives of family caregivers. Dementia [Internet]. 2021 Oct 1 [cited 2022 Feb 22];20(7):2248-60. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1471301221989604?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori%3Arid%3Acrossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub++0pubmed [ Links ]

24. Wells JL, Hua AY, Levenson RW. Poor Disgust Suppression Is Associated with Increased Anxiety in Caregivers of People with Neurodegenerative Disease. Journals Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci [Internet]. 2021 Sep 1 [cited 2022 Feb 22];76(7):1302. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8363043/ [ Links ]

25. Tay DL, Ellington L, Towsley GL, Supiano K, Berg CA. Emotional expression in conversations about advance care planning among older adult home health patients and their caregivers. Patient Educ Couns [Internet]. 2021 Sep 1 [cited 2022 Feb 22];104(9):2232-9. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33658140/ [ Links ]

26. World Health Organization (WHO). World Health Organization(WHO) Definition Of Health - Public Health [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2022 Feb 22]. Available from: https://www.publichealth.com.ng/world-health-organizationwho-definition-of-health/ [ Links ]

27. Kim H, Zhao Y, Kim N, Ahn YH. Home modifications for older people with cognitive impairments: Mediation analysis of caregivers' information needs and perceptions of fall risks. Int J Older People Nurs [Internet]. 2019 Sep 1 [cited 2022 Feb 22];14(3):e12240. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/opn.12240 [ Links ]

28. Kizza IB, Maritz J. Family caregivers for adult cancer patients: knowledge and self-efficacy for pain management in a resource-limited setting. Support Care Cancer [Internet]. 2019 Jun 1 [cited 2022 Feb 22];27(6):2265-74. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30327878/ [ Links ]

29. Chua GP, Ng QS, Tan HK, Ong WS. Caregivers of cancer patients: what are their information-seeking behaviours and resource preferences? Ecancermedicalscience [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2022 Feb 22];14. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7373639/ [ Links ]

30. Sánchez-Huamash CM, Cárcamo-Cavagnaro C. Videos to improve the skills and knowledge of stroke patients' caregivers. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica [Internet]. 2021;38(1):41-8. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34190922/ [ Links ]

Received: February 22, 2022; Accepted: June 29, 2022

text in

text in