Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Enfermería Global

versión On-line ISSN 1695-6141

Enferm. glob. vol.22 no.70 Murcia abr. 2023 Epub 26-Jun-2023

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/eglobal.538551

Originals

Hopelessness in women deprived of liberty and their defense with symptoms of depression and anxiety

1Centro Universitário Tiradentes, Maceió, Alagoas. Brazil

2Associate Professor at the University of Pernambuco/Nossa Senhora das Graças Nursing School (UPE/FENSG)

Professor of the Graduate Nursing. Centro Universitario Tiradentes, Maceió, Alagoas, Brasil

Introduction:

Hopelessness is characterized as the subject's negative outlook on the future. Individuals in deprivation of liberty are predisposed to suffering and loss of hope.

Objective:

To identify the prevalence, level of hopelessness and the correlation with depression and anxiety in women deprived of liberty.

Materials and method:

Quantitative and descriptive cross-sectional study, conducted in a Correctional Facility in Brazil, with 77 women by non-probability sampling. The data collection used were: a) Sociodemographic form; b) Beck Depression Inventory (BDI); c) Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI); and d) Beck Hopelessness Inventory (BSH).

Results:

In the sample, 5.2% of the subjects presented hopelessness with moderate and severe levels. Higher mean scores of hopelessness were perceived in women who never studied (7.33), had no profession (5.04), no religion (7.14), and did not develop labor activities during incarceration (4.86). Higher mean scores of hopelessness were identified in women who had symptoms of depression (5.31) and anxiety (4.63). There was a positive correlation between the BHS and BDI scores.

Conclusion:

There was a low prevalence of hopelessness. It was associated with unfavorable socioeconomic conditions and the lack of work activities during the period of incarceration. Hopelessness correlated with depression, and people with anxiety symptoms had higher levels of hopelessness. It is suggested that hopelessness among people deprived of liberty be investigated in clinical practice and that work and educational activities be promoted during incarceration to promote hope and mental health.

Key words: Anxiety; Depression; Hope; Women; Prisoners

INTRODUCTION

Hope can be defined as a dynamic process and orientation to the future, which attends to the past and is lived in the present, directly implying the establishment and achievement of important goals for the person 1.

Hopelessness, on the other hand, can be understood from the individual's negative perspective about the future 2. Thus, it induces a negative perception of reality and causes damage in all areas of life 3. It can present itself as an isolated symptom, however, it is often associated with other factors, such as emotional style, environmental context and, especially, severe stressful events that cause traumas 4.

In this context, it is noticeable that people in prison are in contact with numerous stressors that predispose them to suffering and loss of hope for the future. Thus, the importance of knowledge about mental illness/suffering and the multifactoriality of this population 5.

The severity of psychological illness is greater among women deprived of liberty, because there is a higher prevalence of abandonment by partners and family members, reflecting in more intense feelings of loneliness, abandonment and interruption of family relationships 6. Feelings that are also related to hopelessness4.

Although there are policies and services implemented in the prison environment, the initiatives are still insufficient to deal effectively with health issues, with emphasis on mental health. Allied to this aspect, it is verified that women deprived of freedom are in an even more worrisome condition, considering that, historically, prisons were designed for the needs of the male population. There is, therefore, the need to provide in the prison setting a comprehensive health care that includes the promotion of mental health of these women, in order to reduce the barriers of access with a focus on deinstitutionalization and not only on female decarceration 7.

Moreover, the latest report of the World Female Imprisonment List (WPB)8) reported that, in the world, there has been a 53.1% increase in the female prison population since the 2000s, leading to more than 714,000 women and girls held in penal institutions in 2017. In Brazil, according to data from the National Survey of Penitentiary Information (Infopen) 9, in December 2019, 37,200 women were deprived of freedom in Brazil, 160 of these in Alagoas.

Therefore, understanding female incarceration means understanding that women in prison constitute an especially vulnerable group, the result of multiple victimizations suffered during their life trajectory and, many times, exposed to revictimization processes as a result of institutional violence experienced in the prison environment with almost twice as many chances of manifesting mental disorders related to hopelessness when compared to other women 7.

Given this context, few current studies were found in the literature that investigate hopelessness and its association with symptoms of depression and anxiety in women deprived of liberty. Knowing these aspects enables a greater contribution of information to support mental health planning for women deprived of liberty in the prison system and also in other community facilities.

Given this context, the present study aims to identify the prevalence and level of hopelessness and its correlation with depression and anxiety in women deprived of liberty.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

This is a quantitative, descriptive, cross-sectional study. The study data collection was carried out with 77 women in deprivation of liberty in a Women's Correctional Facility in Alagoas/Brazil. Data were collected between May 2019 and February 2020.

Sampling was non-probability and convenience sampling. Women who were available on the day of the interviews were invited to participate. Women deprived of liberty aged 18 years or older who had been in prison for at least three months were included. Women who lacked cognitive or psychological conditions and/or who presented significant alterations during data collection were not included in the study.

The participants were informed and signed the Informed Consent Form - ICF and were informed that withdrawal could occur at any stage of the study, according to Resolution 466/12 of the National Health Council. The study is associated with the study: Traumatic experiences in childhood among women deprived of freedom, approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Tiradentes University Center under opinion number 3.539.450.

For data collection we used: a) Sociodemographic form; b) Beck Depression Inventory; c) Beck Anxiety Inventory; and d) Beck Hopelessness Inventory. The Sociodemographic Form was prepared by the study authors for sociodemographic and clinical characterization of the interviewees.

Beck's inventories are screening instruments, adapted and validated for Brazil. They have psychometric properties to evaluate and measure the dimension of symptoms of depression, anxiety and hopelessness 10.

The questions on the Beck Depression Inventory are quantified on a scale from 0 to 4 intensity points. The scores achieved in the items are summed and classified within the overall score, where 0 to 11 corresponds to the minimum level of depression, 12 to 19 to the mild level, 20 to 35 to the moderate level, and 36 to 63 to the severe level 11.

The Beck Anxiety Inventory has questions classified in scales from 0 to 3 points each, in increasing order of anxiety level. The sum of the scores constitutes the total score. This score has a maximum of 63 points and can be classified as: minimal (0 to 10); mild (11 to 19); moderate (20 to 30); and severe (31 to 63) 10.

The Beck Hopelessness Scale, on the other hand, is designed to assess people's negative expectation of the future. It consists of 20 true-false statements, of which 9 are considered false and 11 true. For each statement, there is a score of 0 or 1, in addition to the total "hopelessness" score that is reached by adding up the scores on the individual items, which can be from 0 to 20 2.

In the present study, the cutoff point for the classification "with hopelessness" was 9 points, so only individuals classified with moderate hopelessness/risk of suicide and severe hopelessness/major risk of suicide were considered with hopelessness. Those who scored below 9 points, no hopelessness and mild hopelessness, were classified as "no hopelessness." Secondary variables were those of sociodemographic characterization and levels of depression and anxiety.

Data systematization

The data obtained were entered twice into the Excel® database (version 2007 for Windows version 3.5.3) by different typists and were checked by a third person. Simple frequency analyses of the variables were also performed with the correction of typing errors. The variables were coded for the database in the IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (S.P.S.S.) for Windows version 22.0 statistical package.

Data Analysis Procedure

Data analysis was performed with the aid of SPSS software version 22.0. Descriptive statistics were applied as measures of central tendency as well as measures of dispersion (standard deviation) to describe and investigate the sociodemographic profile and the measure of hopelessness (BHS).

The Shapiro-Wilk test was employed to determine the use of nonparametric and parametric tests. No normalities were identified in the quantitative variables and in the BHS. Thus, to certify that two groups had equal distributions, the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was applied.

The multiple comparisons tests of Campbell and Skillings 12 were applied, in order to find which groups are divergent. There was a 5% significance level in all tests. Regarding the reliability check (degree of correlation between the questionnaire items), the "Cronbach's alpha" coefficient was applied to the total score.

The determination of the degree of correlation of the "BAI" and "BDI" variables with the total score of the "BHS" was done by means of Sperman's non-parametric correlation test as an alternative to Pearson's non-parametric correlation test, since the variables do not have a normal distribution.

The value (r) can range from -1 to +1, where negative values indicate inverse correlation, positive values indicate direct correlation, and zero indicates no correlation. When all the points in the diagram are on a straight line sloping up or down, you get the maximum value of r, either -1 or + 1. When no correlation is identified, the points are distributed in clouds. The intensity of the correlation can be qualitatively evaluated as shown by the criteria set out in Table 1.

RESULTS

In the sociodemographic profile of the sample studied, there was a prevalence of women deprived of liberty aged 30 or more (51.3%), heterosexual (66.2%), black and brown (63.6%), who were never married (42.9%), without partner (62, 3%), with children (79.2%), with no monthly income (68.8%), with a harmonious family relationship (76.6%), with 9 years or less of schooling (59.7%), with a poor or bad school performance (72.6%), with a profession (63.2%) and with religion (89.6%).

Prevalence of hopelessness in women deprived of freedom

In agreement with Table 1, the average BHS score obtained among women deprived of liberty was 4.31. The sample showed reliability, since Cronbach's alpha was 0.76.

Table 1. Relationship of the BHS with the statistics of the study of women deprived of liberty in Maceió - AL, 2018 - 2022.

Source: Elaborated by the authors

As can be seen in Table 2, the data collected on hopelessness in women deprived of liberty, when analyzed, show the prevalence of symptoms of hopelessness in a minimal form in 50.6% of the women and in a mild form in 44.2%.

Table 2. Frequency analysis of hopelessness in women deprived of liberty in Maceió - Alagoas, 2018- 2022.

Source: Elaborated by the authors

Legend:N: Total number. %: Percentage.

Noting that the individuals considered to be hopeless in the present study scored above 9 on Beck's Hopelessness Scale, as can be confirmed in Table 3, 5.2% of the respondents were classified "with hopelessness."

Association between hopelessness and sociodemographic factors

Regarding the association between hopelessness and the sociodemographic variables, higher mean scores of hopelessness were identified in women who never studied (c) (7.33), (p: 0.042**), had no profession (5.04) (p: 0.025*), were not working during the period of imprisonment (4.86) (p: 0.025*), and had no religion (7.14) (p: 0.007*). The variable never studied (c) only showed statistical significance when correlated with the other school performance variables: bad (b), regular, good (a) and excellent (a, b, c), as can be seen in Table 4.

Table 4. Characterization of the sample according to the distribution of means and standard deviations of the scores of the BHS domains regarding women deprived of liberty in Maceió - AL, 2018 - 2022.

Source: Elaborated by the authors;

*p-value obtained by Mann-Whitney test. Significant results in bold.

**p-value obtained by Kruskall-Wallis test.

Association between the symptoms of depression and anxiety and hopelessness

In graph 1, it is possible to observe the relationship between the averages of hopelessness and depression and anxiety. As for depression, the highest mean hopelessness was in women who had depressive symptoms (5.31) compared to those who did not have depression symptoms. Women with anxiety symptoms also had higher mean hopelessness (4.63) compared to those who were not with anxiety symptoms.

Correlation between symptoms of depression and anxiety and hopelessness

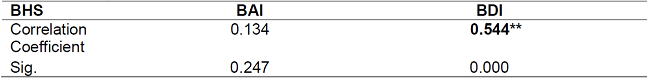

A positive and statistically significant correlation was identified between the BHS and BDI scores. Whereas between the BHS score and BAI no statistically significant correlation was identified as can be seen in Table 5.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, the prevalence of hopelessness among women deprived of liberty was 5.2%, equivalent to the levels of moderate and severe hopelessness. In the current literature, no studies were found to establish a comparison with the population deprived of liberty.

Studies conducted with other publics showed that the prevalence of hopelessness (moderate and severe) was between 2% and 90.4%. The lowest prevalence found was 2% in chronic renal patients on hemodialysis and kidney transplant patients, followed by 3.3% in nursing professionals working in specialized oncology services, 9% in patients in forensic psychiatry, and 90.4% in family members of people with problems related to alcohol and another drug use 3)(13)(14)(15.

In the present study, the mean score of Beck's Hopelessness Scale was 4.30 (SD+/- 2.90). This is lower than that found in the study by Kisa, Zeyneloğlub, and Verimb (16) with 40 women victims of spousal violence residing in a shelter in Turkey, who obtained a mean of hopelessness of 8.60 (SD+/- 4.96). Rueda-Jaimes et al. (17), also found a higher mean hopelessness, 7.8 (SD+/- 5.3), when studying 244 patients with suicidal ideation (63.52% women) seen in the emergency room or outpatient clinic of the Institute of the Eastern Nervous System (ISNOR).

The results of this study also showed that women with worse school performance, who had no religion, had no profession and were not working at the time of incarceration showed higher mean scores of hopelessness when compared to those who were not in these conditions, with statistical significance. It is noteworthy that hopelessness is interconnected to the living conditions of the subject, such as employment, income, and social vulnerabilities 18.

In this sense, the more adverse these conditions are, the greater the levels of hopelessness are likely to be.

Reinforcing these findings, the study of Kisa, Zeyneloğlub and Verimb 16 conducted in a shelter in Turkey, with women victims of spousal violence, also showed that low education and unemployment were associated with hopelessness and feelings such as lack of expectation about the future. It is noteworthy that, in addition to these unfavorable aspects, the lack of job opportunities, leisure and idle time are also factors that favor psychological illness and, consequently, the emergence of higher levels of hopelessness 19. In this sense, the importance of developing labor activities, leisure, education, among others, during the period of incarceration is emphasized, since they bring benefits to mental and physical health and social development 9.

The association between higher levels of hopelessness and having no religion is also an important factor in this context. Practicing religiosity/spirituality is shown as a protective factor for mental health, since it favors resilience and the subject's projection for the future in a more positive and optimistic way 20. Given these aspects, health professionals working in the assistance to women deprived of liberty should discuss religiosity/spirituality in order to stimulate a positive coping, respecting the beliefs, without judgments or impositions.

Also, in the present study, it was evidenced that women with symptoms of depression presented higher mean scores for hopelessness when compared to those who did not have this condition. It is noteworthy that in the correlation study between the BSH and the BDI there was a positive correlation.

Corroborating these data, in the study by Kavak Budak et al. 21, a proportionality between the degrees of depression and hopelessness was identified. This association was also confirmed by the authors Coskun et al. 22 who, when studying medical students, obtained a correlation between the levels of depression and hopelessness.

Still on these aspects, an observational study of 406 patients with depressive disorders evidenced the association between this disorder and hopelessness, even showing that during a depressive episode the level of hopelessness tends to increase, and in remission of depression, to decrease 23. Furthermore, Niu et al. 24 identified hopelessness as an important risk factor for suicide. Thus, the association between hopelessness and depression predisposes the individual to a higher risk of suicidal ideation.

This is due to the fact that hopelessness motivates a pessimistic attitude about the future, leading the person to not know how to react to stressors, since it acts as a mediation channel between psychological suffering and suicidal behavior, serving as a potentiator of such ideations 25.

Regarding the relationship between anxiety and hopelessness, statistical data showed that there was no correlation between BHS and BAI. However, women with anxiety presented higher mean hopelessness, when compared to those who did not present anxiety symptoms.

The authors Hacimusalar et al. 26 point out in their analyses that anxiety levels are an important predictor of hopelessness, considering that they evidenced a directly proportional relationship between anxiety levels and hopelessness. The study by Serin and Dogan 27, conducted with nursing students, also demonstrated this proportional relationship between increased levels of anxiety and hopelessness, corroborating the results of the present study.

The relationship between anxiety and hopelessness can be explained because anxiety is a psychiatric disorder characterized by subjective experiences that lead to excessive worry, negative thoughts, and persistent fear 28. Thus, there is a tendency for individuals with anxiety to have low expectations about their future, that is, to have feelings of hopelessness.

Montaño et al. 29 addressed in his research that participants who presented a high level of anxiety, also had their symptoms of hopelessness elevated, in addition to correlating this result to the fact that people with anxiety have a negative view about the future, which leads them to believe that there is no resolution to their problems, so they tend to be hopeless.

Given the results of the present study, there is an urgent need for research on hopelessness among people deprived of liberty, with emphasis on women, who were the target audience of this research. It is evident that hope is an important factor in the protection and prevention of mental illness 30. Therefore, research on hopelessness, identification of related factors, promotion of work activities, school insertion, stimulus to religiosity/spirituality in the period of incarceration are stimuli that can provide hope to these people about the future.

CONCLUSION

It was identified a low prevalence of moderate and severe hopelessness in women deprived of liberty, but no studies were found with the same public to establish comparison. The highest mean scores of hopelessness were statistically associated with: the worst school performance; not having a profession; not having religion; and not developing a work activity during the period of imprisonment.

The study also showed higher levels of hopelessness in people with symptoms of depression or anxiety, however, only a positive correlation was found between hopelessness and depression. The conditions of the prison environment and the specificities of women deprived of their liberty may further accentuate this relationship between hopelessness and mental disorders.

The research data contribute to highlight the relevance of the perception, identification, and correlation between social vulnerabilities, deprivation of liberty, mental health impairment, and hopelessness. In this sense, in order to promote mental health, it is essential that health professionals have a more focused look at the subjectivity of these women with the identification of factors related to hopelessness and mental illness.

The conditions of the prison environment as well as the promotion of learning opportunities and work activities during the period of incarceration aligned with the qualification of mental health care are factors that can certainly provide a more optimistic projection of these women deprived of liberty for the future.

The study has limitations such as a small sample size, besides the lack of articles about hopelessness in the female population deprived of freedom, and therefore, it was necessary to compare data with other populations, which do not have the same specificities. It is essential that new studies be developed on hopelessness in women deprived of liberty.

REFERENCIAS

1. Querido A. A esperança como foco de enfermagem de saúde mental. Revista Portuguesa de Enfermagem de Saúde Mental. 2018 Nov.[acesso em 22 out. 2021];(spe6):06-08. Disponível em: http://scielo.pt/scielo.php?script=sciarttext&pid=S1647-21602018000200001&lng=pt&nrm=iso. [ Links ]

2. Beck AT, Weissman A, Lester D, Trexler L. The Measurement of pessimism: the hopelessness scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1974;42(6):861-865. Disponível em: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1975-09735-001 [ Links ]

3. Belo, F. M. P. Associação entre desesperança, transtornos mentais e risco de suicídio em profissionais de enfermagem de serviços de oncologia de alta complexidade [dissertação]. Maceió (AL): Universidade Federal de Alagoas; 2018 Apr.[acesso em 03 jun. 2022]. Disponível em: http://www.repositorio.ufal.br/handle/riufal/3181 [ Links ]

4. Fletcher J. Crushing hope: Short term responses to tragedy vary by hopefulness. Soc Sci Med. 2018 Mar.[acesso em 20 out. 2021];201:59-62. Disponível em: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6714575/ [ Links ]

5. Gu H, Lu Y, Cheng Y. Negative life events and nonsuicidal self-injury in prisoners: The mediating role of hopelessness and moderating role of belief in a just world. Journal of clinical psychology. 2020 Jul. [acesso em 23 mar. 2022];77(1):145-155. Disponível em: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342641147_Negative_life_events_and_nonsuicidal_selfinjury_in_prisoners_The_mediating_role_of_hopelessness_and_moderating_role_of_belief_in_a_just_world. [ Links ]

6. Santos MC, Alves VH, Pereira AV, Rodrigues DP, Marchiori GRS, Guerra JVV. Saúde mental de mulheres encarceradas em um presídio do estado do Rio de Janeiro. Texto Contexto - Enferm. 2017 [acesso em 22 jun. 2021];26(02). Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/j/tce/a/3dbSzZsVhz6L8kH97Bpf3YM/abstract/?lang=pt. [ Links ]

7. Schultz ALV, Dotta RM, Stock BS, Dias MTG. Limites e desafios para o acesso das mulheres privadas de liberdade e egressas do sistema prisional nas Redes de Atenção à Saúde. Physis: Revista de Saúde Coletiva. 2020 Nov. [acesso em 22 jun. 2021];30(03). Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/j/physis/a/9ZG5kXknWnwXNJFkyTmBV9m/?lang=pt#. [ Links ]

8. WPB (World Prison Brief). World Female Imprisonment List. 4° ed., nov. 2017 [acesso em 26 jul. 2022]. Disponível em: https://www.prisonstudies.org/resources/world-female-imprisonment-list-4th-edition. [ Links ]

9. BRASIL (Ministério da Justiça e Segurança Pública). Levantamento Nacional de Informações Penitenciárias, atualização jun. 2020 [acesso em 21 jun. 2021]. Brasília: Departamento Penitenciário Nacional. Disponível em: http://antigo.depen.gov.br/DEPEN/depen/sisdepen/infopen. [ Links ]

10. CUNHA JA. Manual da versão em português das Escalas Beck. Casa do Psicólogo. São Paulo; 2001. Disponível em: https://www.scienceopen.com/document?vid=760d7977-aa5a-4b16-be6a-7f84e0aa0201. [ Links ]

11. Bartholomeu D, Machado AA, Spigato F, Bartholomeu LL, Cozza HFP, Montiel JM. Traços de personalidade, ansiedade e depressão em jogadores de futebol. Revista Brasileira de Psicologia do Esporte. 2010 Jan.-Jun. [acesso em 22 jun. 2021];3(4):98-114. Disponível em: http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/pdf/rbpe/v3n1/v3n1a07.pdf. [ Links ]

12. Campbell G, Skillings JH. Nonparametric Stepwise Multiple Comparison Procedures. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1985 Dec.[acesso em 07 abr. 2022];80(392):998-1003. Disponível em: https://www.jstor.org/sTable/2288566. [ Links ]

13. Andrade SV, Sesso R, Diniz DHMP. Desesperança, ideação suicida e depressão em pacientes renais crônicos em tratamento por hemodiálise ou transplante. J. Bras Nefrol. 2015 Jan.-Mar. [acesso em 03 jun. 2022];37(1). Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/j/jbn/a/Qmgh6vDrBBcLVffsZN4jWGB/abstract/?lang=pt. [ Links ]

14. Büsselmann M, Nigel S, Otte S, Lutz M, Franke I, Dudeck M, Streb J. High Quality of Life Reduces Depression, Hopelessness, and Suicide Ideations in Patients in Forensic Psychiatry. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2020 Jan. [acesso em 29 mar 2022];10(1014). Disponível em: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32038334/. [ Links ]

15. Moraes MAS, Júnior EBC, Fernandes MNF, Prudente COM. Factors that influence the quality of life and hopelessness on family members of drug addicts. Research, Society and Development. 2020 Jun. [acesso em 1 dez. 2021];9(8). Disponível em: https://rsdjournal.org/index.php/rsd/article/view/5037 [ Links ]

16. Kisa S, Zeyneloglu S, Verim ES. The Level of Hopelessness and Psychological Distress among Abused Women in A Women's Shelter in Turkey. Archives of psychiatric nursing. 2019 Feb. [acesso em 15 dez. 2021];33(1):30-36. Disponível em: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30663622/. [ Links ]

17. Rueda-Jaimes GE, Castro-Rueda VA, Rangel-Martínez-Villalba AM, Moreno-Quijano C, Martinez-Salazar GA, Camacho PA. Validation of the Beck Hopelessness Scale in patients with suicide risk. Rev. de Psiquíatria y Salud Mental. 2018 Apr-Jun. [acesso em 18 jun. 2021];11(2):86-93 Disponível em: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1888989116300921. [ Links ]

18. Fortuna KL, Venegas M, Bianco CL, Smith B, Barsis JA, Walker R, Brooks J, Umucu E. The relationship between hopelessness and risk factors for early mortality in people with a lived experience of a serious mental illness. Soc. Work Ment Health, 2020 Jan. [acesso em 20 jul. 2022];18(4). Disponível em https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33442334/. [ Links ]

19. Bahiano MA. Depressão e enfrentamento de diversidade em pessoas sob condição de privação de liberdade [dissertação]. São Cristóvão (SE): Universidade Federal de Sergipe; 2019 Aug. [acesso em 02 nov. 2021]. Disponível em: https://ri.ufs.br/handle/riufs/12539. [ Links ]

20. Fleury LFO, Gomes AMT, Rocha JCCC, Formiga NS, Souza MMT, Marques SC, et al. Religiosidade, estratégias de coping e satisfação com a vida: Verificação de um modelo de influência em estudantes universitários. Revista Portuguesa de Enfermagem de Saúde Mental, 2018 Dec. [acesso em 11 jun. 2022];(20):51-57. Disponível em: https://scielo.pt/scielo.php?script=sciartte xt&pid=S1647-21602018000300007&lng=pt&nrm=iso&tlng=pt?script=sciartte x&pid=S1647-21602018000300007&lng=pt&nrm=iso&tlng=pt. [ Links ]

21. Kavak Budak F, Özdemir A, Gültekin A, Ayhan MO, Kavak M. The Effect of Religious Belief on Depression and Hopelessness in Advanced Cancer Patients. J Relig Health. 2021 Jan. [acesso em 16 mai. 2022];60:2745-2755. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-020-01120-6. [ Links ]

22. Coskun O, Ocalan AO, Ocbe CB, Semiz HO, Budakoglu I. Depression and hopelessness in pre-clinical medical students. Clin Teach. 2019 Aug.[acesso em 25 jul. 2022];16(4):345-351. Disponível em: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31397111/. [ Links ]

23. Baryshnikova I, Rosenström T, Jylhä P, Koivisto M, Mantere O, Suominen K, Isometsä ET. State and trait hopelessness in a prospective five-year study of patients with depressive disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2018 Oct.[acesso em 23 jul. 2022];239:107-114. Disponível em: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0165032718310255. [ Links ]

24. Niu L, Jia C, Ma Z, Wang G, Sun B, Zhang D, et al. Loneliness, hopelessness and suicide in later life: a case-control psychological autopsy study in rural China. Epidemiology and psychiatric sciences. 2020 Apr.[acesso em 25 nov. 2021];29,e119. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796020000335. [ Links ]

25. Lew B, Huen J, Yu P, Yuan L, Wang DF, Ping F, et al. Associations between depression, anxiety, stress, hopelessness, subjective well-being, coping styles and suicide in Chinese university students. PLoS ONE. 2019 Jul. [acesso em 20 jul.2022];14(7). Disponível em: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6602174/pdf/pone.0217372.pdf. [ Links ]

26. Hacimusalar Y, Kahve AC, Yasar AB, Aydin MS. Anxiety and hopelessness levels in COVID-19 pandemic: A comparative study of healthcare professionals and other community sample in Turkey. J Psychiatr Res. 2020 Oct.[acesso em: 20 jul.2022];(129):181-188. Disponível em: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32758711/. [ Links ]

27. Serin EK, Dogan R. The Relationship Between Anxiety and Hopelessness Levels Among Nursing Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic and Related Factors. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying. Forthcoming jul. 2021 [acesso em 20 jul.2022]. Disponível em: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/00302228211029144?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori%3Arid%3Acrossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub++0pubmed&. [ Links ]

28. Quevedo J, Izquierdo I. Neurobiologia dos transtornos psiquiátricos. Porto Alegre, editora Artmed; 2020. [ Links ]

29. Montaño AH, Tovar JG, Sánchez RIG, García KV, Pedraza BAG. Ansiedad, desesperanza y afrontamiento ante el COVID-19 en usuarios de atención psicológica. Actualidades en Psicología. 2022 Jan-Jun.[acesso em 23 jul. 2022];36(13):17-28. Disponível em: https://doaj.org/article/51c656174b9a4c61909e46c0f0076d08. [ Links ]

30. Querido A, Dixe M. A esperança na saúde mental: Uma revisão integrativa da literatura. Revista Portuguesa de Enfermagem de Saúde Mental. 2016 Apr.[acesso em 08 jan. 2022];(spe3):95-101. Disponível em: https://scielo.pt/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1647%2021602016000200016&lng=pt&nrm=iso&tlng=pt?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1647-21602016000200016&lng=pt&nrm=iso&tlng=pt. [ Links ]

Received: September 11, 2022; Accepted: October 13, 2022

texto en

texto en