Meu SciELO

Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Enfermería Global

versão On-line ISSN 1695-6141

Enferm. glob. vol.22 no.71 Murcia Jul. 2023 Epub 13-Nov-2023

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/eglobal.555391

Reviews

Dilemmas of conscientious objection in the voluntary interruption of pregnancy: integrative literature review

1Nursing department. University of Chile. Santiago de Chile. Chile

2Center for Studies and Research in Health and Society. Faculty of Medical Sciences. Bernardo O'Higgins University. Santiago de Chile. Chile

Introduction:

Conscientious objection (CO) can generate a conflict for health professionals on issues such as voluntary interruption of pregnancy (IVE).

Method:

Integrative literary review in six stages, obtained from the MEDLINE/PUBMED, ISI Web of Science, LILACS, and SciELO databases published between 2018-2022 in English, Portuguese, and Spanish, adjusted to PRISMA requirements. Data were summarized using thematic analysis.

Results:

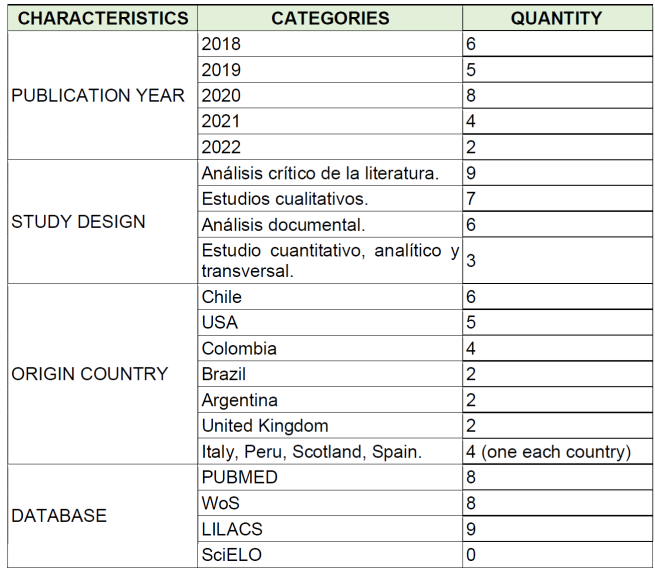

From 55 texts, 25 were analyzed. 32% of the publications were made in 2020, 36% are critical analyses of the literature, 24% were made in Chile, and 32% were obtained from PUBMED. Three categories of work are accepted: 1. Characteristics of the CO. How does CO affect public health? 2. The advisability of proceeding to a regulation of the exercise of the CO.3. CO challenges.

Conclusions:

The aspects that support professional attitudes are problematized, insisting that, although the law recognizes the exercise of CO in the health field, it is necessary to articulate bidirectional protection; in this way, CO is legitimized and acquires coherence, ensuring the right to health of women. Thus, his argument resides in the understanding that the main commitment of health teams is the well-being of women's sexual and reproductive health in all contexts.

Key words: Abortion; Personal Autonomy; Reproductive-Rights; Abortion, Legal; Public Policy

INTRODUCTION

Conscientious Objection (CO) arises in the military as an opportunity to refuse to participate in compulsory military service for moral or religious reasons. In the health field, the OC describes the ability of service providers to refuse to carry out certain activities -such as the Voluntary Interruption of Pregnancy (IVE)- due to generating conflicts regarding their beliefs. At this point, there is a problem between the rights of people to receive health care and the health team to act following their conscience(1).

The literature indicates that CO is used to limit access to abortion, ceasing to provide this care(2), and maybe misused and put women's health care at risk as rights holders. In addition, international and human rights organizations have identified the use of CO to deny access to abortion services, requesting countries to protect their entry from the limits established between a democratic rule of law and the current ethical guidelines concerning health and the needs of vulnerable people(3).

Chile modified the abortion law in August 2017, going from prohibiting all abortions to allowing them under three grounds: (C1) due to risk to the life of the woman, (C2) lethal malformation of the fetus, and (C3) pregnancy resulting from a violation. There was no existing regulation regarding the exercise of CO(4). However, law 21,030 was amended to allow health institutions and a wide range of clinical and non-clinical health personnel to request CO(4),(5). In this sense, any private institution can refuse to provide abortion services; if an institution requests CO, its health professionals are not authorized to offer abortion services, regardless of their position.

Nevertheless, to ensure that CO does not impede access to legal abortion or postabortion care, objecting providers must register by notifying their institution's authority, referring all women seeking a legal abortion to a non-objecting provider. In this context, the CO has played a dominant role during the implementation of the law, given the proportion of officials who are conscientious objectors(4),(6). Regarding the institutional CO, according to official information as of January 2019, in Chile, only seven health establishments have declared objections; one for C3, and the others object on all grounds(4).

As of October 2022, of 1,338 gynecologists-obstetricians hired in the 29 Chilean public health services, 15% are objectors for C1, 23% for C2, and 43% for C3. Regarding the health team members related to the IVE, of 924 anesthesiologists (March 2022), 11% objected to C1, 14% to C2, and 21% to C3. Of the non-medical professionals, 9% objected to C1, 12% to C2, and 16% to C3. Regarding the technical personnel who work inside the pavilion, 10% object for C1, 11% for C2, and 13% for C2(6). This national percentage distribution for 2022 maintains similar trends compared to 2019(7). In addition, the literature has managed to problematize the issue of CO at the individual level, raising arguments that emphasize medical-religious, conservative discourses, reasons other than morality, or lack of trained health providers.

In Chile, this is worrying since it could generate inequalities because the CO can limit women's timely and effective access to the benefits guaranteed in Law 21,030. At the international level, the same tensions regarding the implementation of this public policy impact health processes; where although the regulations recognize the exercise of CO in the field of health, it is necessary to articulate two-way protection so that it is legitimate and coherent, for one hand, and ensure women's right to health, on the other. These restrictions raise questions about access to legitimate benefits for specific groups, considering the objectives of medicine, public health, and the fulfillment of the rights and interests of women in conflict, highlighting the commitment of health teams to care for the well-being, sexual and reproductive health of women, opening the way to the construction of the concept of biological citizenship.

With this background, the objective of this article is to analyze the arguments that are at stake in the CO in the context of IVE from the point of view of those who provide health care, as well as the elements that come into conflict in terms of public health; contributing to the public debate on CO, based on the main theoretical components described in recent literature.

MATERIAL AND METHOD

This study is a six-step integrative review of the literature. This type of review allows for summarizing the information available regarding the subject matter through analyzing various studies(8).

Method: 1) identification of the problem 2) determination of the search strategy and determination of inclusion and exclusion criteria 3) definition of the information to be extracted from the selected studies/categorization of studies 4) evaluation of the studies included in the integrative review 5) interpretation of study results and 6) presentation of the review/synthesis of knowledge(8). For the development of this stage, the work is carried out through a data analysis matrix and the elaboration of descriptive Tables.

The question guided the review: What are the arguments and critical issues at stake in the CO in the context of IVE, from the point of view of those who provide health care that affects public health between 2018-2022?

Regarding the eligibility criteria:

Inclusion criteria (IC): Scientific journal; full text online; the central relationship between CO, abortion, reproductive rights, caregivers, and public health policies; critical or documentary analysis articles; studies with qualitative, quantitative methodological approach and case studies.

Exclusion criteria (EC): methodologically incomplete articles; articles in a language other than Spanish, English, or Portuguese; papers with references to CO among other main professionals; essays; letters to the editor.

The search period was in October and November 2022, searching for studies between 2018 and 2022, in Spanish, English, and Portuguese, in the PUBMED, WoS, LILACS, and SciELO databases, with detailed search strategies in Table 1.

For data selection, the modified PRISMA(9) methodology (Figure 1) was used to delimit the final texts and present the data(8): Step 1: articles published from 2018 to 2022. Step 2: detailed reading of the title and summary of the articles, selecting according to CI and CE. Step 3: identification of final articles. Step 4: categorizes texts into three thematic areas: 1) Characteristics of CO in the health team AND How does CO affect public health?; 2) The advisability of proceeding to a regulation of the exercise of CO; and 3) Challenges regarding CO. Finally, a thematic analysis of Minayo was developed, categorizing the findings with a qualitative-narrative synthesis of the results(8).

RESULTS

Characterization of the studies

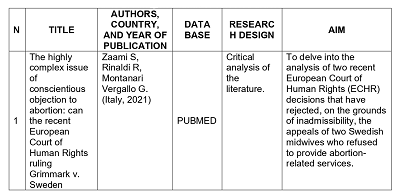

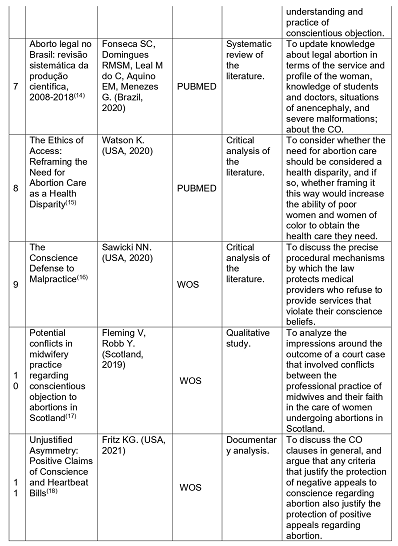

Of the 55 documents found, 30 met the search criteria. Finally, 25 completed the criteria (Figure 1. PRISMA Diagram) and are presented in Tables 2 and 3. The descriptive analysis (Table 2) highlights 32% of the publications were made in 2020, followed by 2018; 36% are critical analyses of the literature, followed by qualitative studies; 24% were carried out in Chile, and 32% were obtained from PUBMED.

DISCUSSION

It is inferred that the different categories highlight the interest of the research community in characterizing CO with arguments associated with its characteristics, how it affects public health, the convenience of proceeding with a regulation of the exercise of CO among the health team, and the challenges that the literature highlights, in terms of CO.

1. Characteristics of the OC. How does OC affect public health?

The decision to provide or oppose abortion services remains ethically complex, with arguments for and against it(19). The CO reproduces doubts regarding abortion laws and care protocols, sexist stereotypes, and gender inequalities, as well as attachment to biomedical powers and control of pregnant bodies(24) in multifaceted individual situations of care(23) (25) (26). The CO constitutes a means that guarantees the autonomy of the individual from the State, governing her life according to his moral convictions(22),(27).

Ramsayer et al. emphasizes that respecting conscience and recognizing this ambiguity allows us to understand the decisions of the members of the health team(19) from points of view regarding the limits of participation in abortion matters(17). There are multiple motivations for using CO in denial of abortion(11), highlighting a combination of political, social, and personal factors; adding(12) ideological reasons as a central discursive element, interpreting it as a refined system of internal sabotage in health care for women, avoiding responsibilities(4). Additionally, a series of prejudices are raised that are medical, legal, and social at the same time, which translates into the unilateral exercise of power, denying the service to those who require IVE(24). The situation is aggravated when states immunize health care providers from consequences(16).

Harris(13) and Fleming et al.(17) highlight that CO policies and debates worldwide do not consider the different pressures that influence health professionals; to decide in the face of this dichotomous situation. So, suppose legal dispensations are established for reasons of conscience not to perform abortions where it is legal; in that case, the same exceptions should be considered to commit them in places where it is illegal(18). Therefore, there is a need to find a balance so that the CO responds to the needs of all professionals on the issue of abortion, providing equiTable care to women within the framework of human rights(4) (7) (20) (29) and respect for people as moral agents(15). In the particular case of abortion, this limit would be represented by the woman's right to access the termination of pregnancy legally, safely, and without discrimination(10),(19).

From a public health perspective, it is not possible to defend CO only when it is adapted to personal purposes on the subject of abortion(18),(27) since it exhibits an obstacle in defense of reproductive autonomy, limiting safety for women, women, promoting inequities in health and presenting a deontological perspective related to early sexual education that can impact human behavior(27). In this, the main consequences of CO are delays in abortion services, conflicts within the team(19), and access to health benefits, which leads to a greater risk of morbidity and death for those who seek an abortion outside the system(13). The texts highlight that abortion is not only a decision attached to the citizen logic of law but faces existential dilemmas between its secular and secular representation with religious beliefs about human reproduction. In this way, citizen deliberation on CO matters should respect people's moral capacity or ethical action and stimulate value diversity and a plurality of thought and ideology so that its implementation strengthens democratic coexistence(30).

Finally, health professionals must reflect on how to achieve the coexistence of the right to freedom of thought with the organization of services in such a way as to guarantee the free exercise of a Rule of Law, especially for women. If this is not achieved, there is a risk that laws will be enacted that allow both public and private health providers to exercise CO(21) (28) (30). Nonetheless, it is expected that public institutions comply with the execution of public policies without refusing to provide benefits, as well as private establishments that receive state contributions. Even so, instances are necessary to effectively supervise and regulate the exercise of CO, in addition to incorporating ethical aspects and sexual and reproductive rights(24) in the education and training of health teams to make informed decisions(4) (25) (26).

2. The advisability of proceeding to a regulation of the exercise of the CO

Numerous bioethical and legal reasons, especially the assurance of women's reproductive rights, justify the need for CO regulation; in the broad and diverse regulatory contexts that have made it difficult for women to access abortion services(3). This overprotection of CO can immunize healthcare providers from various potential adverse consequences, including civil liability, criminal prosecution, professional discipline, employment discrimination, segregation in educational opportunities, and denial of public funding or private, among others(16).

Although CO has been legitimized personally, institutional CO is questionable. This is how Chilean regulations(3) allow establishments to define CO according to its guidelines, although its reasonable application at this level should be questioned(28). This is because(4) it becomes another limitation for women's access to the benefits guaranteed in Law 21,030.

Developing rules regarding a perspective of mutual agreement or balance(4) (7) (20) represents a challenge to achieve, on the one hand, the protection of the conscience of women who request legal abortion; and, on the other, the defense of those who provide health services, whether they refuse or provide the service(29).

3. CO challenges

For the CO exercise to be carried out by adapting to individual characteristics, citizens, and states, the literature studied highlights:

First, promote widespread understanding, build agreement on issues that may have far-reaching consequences, respecting conscience since the decision to provide or oppose abortion services is ethically complex given the arguments for and against(19),(30). Recognizing the process to achieve civic and democratic maturity that recognizes the right of women to decide over their bodies(30).

Second, promote training on legal abortion, IVE, and CO among the health team; the evidence confirms that knowledge and training are scarce in these topics(14). Thus, the new professional generations appear strengthened in reproductive autonomy(25). By presenting greater theoretical and practical instruction, make decisions and carry out autonomous actions with ethical sensitivity to prevent moral and emotional repercussions(4),(26).

Third, policymakers and stakeholders must focus on creating and maintaining proper healthcare environments and removing the stigma associated with these services(12),(13).

Fourth, work on clear guidelines for health professionals, specific regulatory recommendations on CO, including limits and obligations, and suggestions for government and health system leaders(17) (19) (23) (29).

Fifth, the CO must be placed in balance with the rights of the users so that in all circumstances, both the conscience of the provider or of those who object and of the women requesting IVE(29) are protected. These mutually agreed regulations will make it possible to provide optimal care to women within a human rights framework(20),(29). Sixth, public and private institutions with state contributions must be aligned with public policies without refusing to provide benefits. The respective inspection is essential(4).

CONCLUSIONS

This study managed to answer the guiding question, highlighting that despite the heterogeneity found in the reasons for taking advantage of the CO -from Catholic fundamentalism to work overload- or providing IVE, it continues to be a decisional and deliberative process that it must take into account many individual aspects that are constrained or driven by disparate legal regulations around the world, which rarely take into account how the context in which reproductive health care is provided will affect the practice of CO.

Even so, perspectives of the power of contemporary medical knowledge on female bodies are maintained, which are necessary to transform by enhancing reproductive autonomy in general, to allow women to enjoy life as integral social beings, which, among other things interests, you can choose your reproductive future.

However, the final reflection is that this reproductive right is often disrespected and limited in its ethical validity, being justified by norms, interrelated with gender, tradition, religion, social condition, age, and education, by gender inequalities, due to social and historical norms, which give others the power to control women's decisions about sexual, reproductive, and maternity behavior. In this, recognizing the advisability of proceeding to a regulation of the exercise of CO in the field of public health is beneficial since it guarantees the rights and duties of the users of the health systems, provides legal certainty to objectors and care centers of health, and establishes when the CO responds to the exercise of ideological and religious freedom protected by legal bodies, limiting the crossroads that underlie decision-making.

REFERENCIAS

1. Fleming V, Frith L, Luyben A, Ramsayer B. Conscientious objection to participation in abortion by midwives and nurses: a systematic review of reasons. BMC Medical Ethics [Internet]. 2018 [citado 4 de marzo de 2023];19(1):1-13. Disponible en: https://bmcmedethics.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12910-018-0268-3 [ Links ]

2. Awoonor-Williams JK, Baffoe P, Ayivor PK, Fofie C, Desai S, Chavkin W. Prevalence of conscientious objection to legal abortion among clinicians in northern Ghana. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics [Internet]. 2018;140(1):31-6. [ Links ]

3. Marshall P, Zúñiga Y. The overprotection of conscientious objection in Chile's abortion regulation. Developing World Bioethics [Internet]. 2021 [citado 4 de marzo de 2023];21(2):58-62. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1111/dewb.12303 [ Links ]

4. Montero Vega A, Ramírez-Pereira M. Noción y argumentos sobre la objeción de conciencia al aborto en Chile. Revista de Bioética y Derecho [Internet]. 2020 [citado 4 de marzo de 2023];(49):59-75. Disponible en: https://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?pid=S1886-58872020000200005&script=sci_arttext&tlng=pt [ Links ]

5. Salas SP. La objeción de conciencia en la educación médica. Una propuesta para Chile. Revista médica de Chile [Internet]. 2019 [citado 4 de marzo de 2023];147(8):1067-72. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0034-98872019000801067 [ Links ]

6. Ministerio de Salud, Chile. Funcionarios objetores de conciencia por Servicio de Salud a marzo 2022 [Internet]. 2023 [citado 4 de marzo de 2023]. Disponible en: https://www.minsal.cl/funcionarios-objetores-de-conciencia-por-servicio-de-salud/ [ Links ]

7. Montero A, Ramírez-Pereira M, Robledo P, Casas L, Vivaldi L, Molina T, et al. Prevalencia y características de objetores de conciencia a la Ley 21.030 en instituciones públicas. Revista chilena de obstetricia y ginecología [Internet]. 2021 [citado 4 de marzo de 2023];86(6):521-8. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.24875/rechog.21000006 [ Links ]

8. Souza MT de, Silva MD da, Carvalho R de. Revisão integrativa: o que é e como fazer. Einstein (São Paulo) [Internet]. 2010 [citado 25 de septiembre de 2020];8(1):102-6. Disponible en: https://www.scielo.br/pdf/eins/v8n1/pt_1679-4508-eins-8-1-0102 [ Links ]

9. Hutton B, Catalá-Lopez F, Moher D. The PRISMA statement extension for systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analysis: PRISMA-NMA. Med Clin (Barc) [Internet]. 2016 [citado 4 de agosto de 2021];147(6):262-6. Disponible en: https://reader.elsevier.com/reader/sd/pii/S0025775316001512?token=E71AE17868A425C2D8A9022E24CAD60052828E602EC5C64896DA7474EF60CA1B80398F5672A5975906ED3AD8F177DB7E&originRegion=us-east-1&originCreation=20210804172956 [ Links ]

10. Zaami S, Rinaldi R, Montanari Vergallo G. The highly complex issue of conscientious objection to abortion: can the recent European Court of Human Rights ruling Grimmark v. Sweden redefine the notions of care before freedom of conscience? The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care [Internet]. 2021 [citado 4 de marzo de 2023];26(4):349-55. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1080/13625187.2021.1900564 [ Links ]

11. Michel AR, Kung S, López-Salm A, Navarrete SA. Regulating conscientious objection to legal abortion in Argentina: Taking into consideration its uses and consequences. Health and Human Rights [Internet]. 2020 [citado 4 de marzo de 2023];22(2):271. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7762910/ [ Links ]

12. Branco JG de O, Brilhante AVM, Vieira LJE de S, Manso AG. Objeção de consciência ou instrumentalização ideológica? Uma análise dos discursos de gestores e demais profissionais acerca do abortamento legal. Cadernos de Saúde Pública [Internet]. 2020 [citado 4 de marzo de 2023];36. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311X00038219 [ Links ]

13. Harris LF, Halpern J, Prata N, Chavkin W, Gerdts C. Conscientious objection to abortion provision: why context matters. Global public health [Internet]. 2018 [citado 4 de marzo de 2023];13(5):556-66. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2016.1229353 [ Links ]

14. Fonseca SC, Domingues RMSM, Leal M do C, Aquino EM, Menezes G. Aborto legal no Brasil: revisão sistemática da produção científica, 2008-2018. Cadernos de Saúde Pública [Internet]. 2020 [citado 4 de marzo de 2023];36. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311X00189718 [ Links ]

15. Watson K. The ethics of access: Reframing the need for abortion care as a health disparity. The American Journal of Bioethics [Internet]. 2022 [citado 4 de marzo de 2023];22(8):22-30. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1080/15265161.2022.2075976 [ Links ]

16. Sawicki NN. The conscience defense to malpractice. Calif L Rev [Internet]. 2020 [citado 4 de marzo de 2023];108:1255. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.15779/Z380P0WRG5 [ Links ]

17. Fleming V, Robb Y. Potential conflicts in midwifery practice regarding conscientious objection to abortions in Scotland. Nursing ethics [Internet]. 2019 [citado 4 de marzo de 2023];26(2):564-75. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1177/096973301770833 [ Links ]

18. Fritz KG. Unjustified asymmetry: Positive claims of conscience and heartbeat bills. The American Journal of Bioethics [Internet]. 2021 [citado 4 de marzo de 2023];21(8):46-59. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1080/15265161.2020.1863514 [ Links ]

19. Ramsayer B, Fleming V. Conscience and conscientious objection: The midwife's role in abortion services. Nursing ethics [Internet]. 2020 [citado 4 de marzo de 2023];27(8):1645-54. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0969733020928416 [ Links ]

20. Maxwell C, Ramsayer B, Fleming V. It's about finding a balance... exploring conscientious objection to abortion with UK midwives. Midwifery [Internet]. 2022 [citado 4 de marzo de 2023];112:103416. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2022.103416 [ Links ]

21. Cuesta JDC. Objeción de conciencia de las personas organizacionales en Colombia. Ciencias Sociales y Educación [Internet]. 2018 [citado 4 de marzo de 2023];7(14):39-64. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.22395/csye.v7n14a3 [ Links ]

22. Del Risco JAC, Santana GF. La afectación al derecho a la vida y el tratamiento de la objeción de conciencia en el Perú. Revista General de Derecho Canónico y Derecho Eclesiástico del Estado. 2021;(57):15. [ Links ]

23. Fleming V, Ramsayer B, Zaksek TS. Freedom of conscience in Europe? An analysis of three cases of midwives with conscientious objection to abortion. Journal of medical ethics [Internet]. 2018 [citado 4 de marzo de 2023];44(2):104-8. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2016-103529 [ Links ]

24. Botero SS, Cárdenas R, Zamberlin N. ¿De qué está hecha la objeción? Relatos de objetores de conciencia a servicios de aborto legal en Argentina, Uruguay y Colombia. Sexualidad, Salud y Sociedad (Rio de Janeiro) [Internet]. 2020 [citado 4 de marzo de 2023];137-57. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1590/1984-6487.sess.2019.33.08.a [ Links ]

25. Moure Soengas A, Cernadas Ramos A. Percepción del alumnado de medicina sobre la objeción de conciencia a la interrupción voluntaria del embarazo en Galicia. Gaceta Sanitaria [Internet]. 2020 [citado 4 de marzo de 2023];34:150-6. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaceta.2019.02.007 [ Links ]

26. Martínez-Sánchez J, Trujillo-Numa L, Montoya-González L, Restrepo-Berna DP. Actitudes, conocimientos y prácticas de internos de medicina frente a la interrupción voluntaria del embarazo en Medellín, Colombia. Revista Médica de Risaralda [Internet]. 2019 [citado 4 de marzo de 2023];25(2):149-56. Disponible en: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0122-06672019000200149 [ Links ]

27. Vicco MH, Zamora MAG. Objeción de conciencia como necesidad legal: una mirada desde el aborto. Revista Bioética [Internet]. 2019 [citado 4 de marzo de 2023];27(3):528-34. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1590/1983-80422019273337 [ Links ]

28. Cabello-Robertson J, Núñez-Nova A. Objeción de conciencia institucional y regulación en salud: ¿existe una excusa legítima frente al aborto en Chile? Revista de Bioética y Derecho [Internet]. 2018 [citado 4 de marzo de 2023];(43):161-77. Disponible en: https://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1886-58872018000200012 [ Links ]

29. Gonzalez Velez AC. Conscientious Objection, Bioethics and Human Rights: A Perspective from Colombia. Rev Bioetica & Derecho. 2018;42:105. [ Links ]

30. Robledo P. Objeción de conciencia: entre libertades y derechos. Revista Chilena de Salud Pública [Internet]. 2018 [citado 4 de marzo de 2023];22(2):179-87. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.5354/0719-5281.2018.53249 [ Links ]

Received: February 03, 2023; Accepted: April 18, 2023

texto em

texto em