Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Enfermería Global

versión On-line ISSN 1695-6141

Enferm. glob. vol.22 no.72 Murcia oct. 2023 Epub 04-Dic-2023

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/eglobal.558881

Originals

Sociodemographic characteristics, life habits and health conditions of people deprived of liberty

1Doctoranda en Enfermería por la Universidad Federal del Paraná, Estado del Paraná. Brasil

Enfermera en la Penitenciaría Estadual de Foz do Iguaçu, vinculada a Secretaría de Estado de la Seguridad Pública y Administración Penitenciaria, Estado del Paraná. Brasil

2Doctora en Enfermería por la Universidad de São Paulo. Brasil. Profesora Titular jubilada de la Universidade Federal del Paraná (UFPR). Brasil

3Doctora en Enfermería UFPR. Profesora Adjunta del Curso de Enfermería de la Universidad Federal del Paraná. Brasil

4Doctora en Enfermería. Profesora Titular de la Escuela de Enfermería de la Universidad Federal de Bahia (EEUFBA). Brasil

5Doctorado en Enfermería por la Universidad Federal de Bahia. Profesora Asociada II de la Universidad Federal de Bahia. Brasil

The deprivation of liberty, due to its characteristics, imposes on people differentiated habits and customs that can influence their health. In that sense, the objective of this is to verify the prevalence of chronic diseases in the prison population. This is a cross-sectional descriptive study, carried out in four prison unity in a city in southern Brazil. Data collection was performed by a semi-structured instrument and descriptive statistics were used for analysis. Participated 326 people deprived of freedom, 90.8% were male, 53.4% young, aged between 18 and 29 years, 43.3% single, 55.8% with less than nine years of schooling, 61.3% performed some activity in the penal unit, 63.2% were smokers or former smokers, 28.2% drank alcohol and 60.4% used or ex used illicit drugs, 71.2% practiced physical activities, 86.1% positively evaluated their health status and 52.5% reported some chronic disease. The most prevalent self-reported diseases were respiratory, gastrointestinal, mental, cardiovascular, and musculoskeletal. People deprived of freedom have chronic diseases and risk factors prevalent in the general population. Knowing the epidemiological profile of this population group can contribute to health-promoting actions, prevention, and control of risk factors.

Keywords: Adult Health; Chronic Diseases; People Deprived of Liberty; Prison; Prisoners

INTRODUCTION

The prison system must promote health care equivalent to the community health in general, whose objectives must not differ from those outside the prison, which are related to recovery, prevention and health promotion. Health professionals should try to minimize the negative effects of prison, favoring conditions so that People Deprived of Liberty (PDL) do not leave prison in worse health conditions than when they entered the penal unit. Among the health conditions recommended for medical care are mental health, chemical dependency problems, infections and acute or chronic illnesses (1).

The present study considers that the way of life of population groups produces different patterns of illness and health maintenance, which vary in society and among individuals. In this sense, knowing the people deprived of liberty health implies understanding specific aspects of the prison context, without excluding it from the public health system that deals with the well-being of society in general (2).

In the Brazilian context, prison health is guided by Interministerial Ordinance No. 1 of 2014, which establishes the National Health Care Policy for People Deprived of Liberty in the Prison System (PNAISP). This ordinance guarantees PDL access in the prison system to comprehensive care in the Unified Health System (SUS) through the Health Care Networks (RAS); and by the 2017 National Primary Care Policy (PNAB), which incorporates it as a component of primary care (3,4).

Therefore, the concept of health to be offered to the PDL is that apprehended in the 1988 Constitution, which considers it to result from the conditions of food, housing, education, income, environment, work, transportation, leisure, employment, freedom; as well as, in a strict sense, related to illness (5). The expansion of this concept will guide this analysis.

Emphasizing that investigations into the health conditions of prisoners are scarce, as pointed out in the Public Hearing of the Social Security and Family Commission (2021), the lack of detailed information on the health of PDL in Brazil makes it difficult to prevent and treat diseases with higher incidence in this specific population (6). Thus, the objective of this study is to contribute with the description of sociodemographic characteristics, lifestyle habits and health conditions of people deprived of liberty.

METHODOLOGY

This research is a descriptive cross-sectional study, carried out in a triple border city and is part of a larger study entitled: “Chronic disease and health of People Deprived of Liberty in the light of the Salutogenic Theory: study of mixed methods”. The data discussed here are related to the quantitative phase. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) recommendations were applied to the study (7).

The research was carried out in four prison units in the municipality of Foz do Iguaçu, located in the southern region of Brazil, bordering Paraguay and Argentina, from April to August 2021. The city has the second largest prison population in the state from Paraná, with 2335 PDL. Three units (I, II, III) are for males and the fourth (IV) is for females, all over the age of 18 (8).

The selection of participants took place through proportional stratified probabilistic sampling, considering the number of PDL in each of the four prison units. The margin of error was 5%, confidence level 95% and expected frequency of the event of interest in the population was 50%. The sample to represent the total population was calculated using the Epi Info 7 software in 326 individuals. In each unit, a simple random selection was made using Excel software, based on the alphabetical lists available in the prison units.

For data collection, a self-completed semi-structured questionnaire was used, adapted from the Multidisciplinary Study Group on Adult Health (GEMSA) of the Federal University of Paraná (UFPR). This questionnaire consists of sociodemographic, occupational, clinical and lifestyle variables, with 19 questions which two was discursive, nine objective and eight mixed. In addition, the questionnaire consisted of a question that assessed the perceived state of health, using a five-point Likert scale. It was based on the PDL's self-declaration.

Inclusion criteria were: being imprisoned in the prison units of this triple-border city; deprived of liberty for more than six months; and, as exclusion criteria, refusal to participate in the study. The discontinuity criteria were: request, verbal or written, for exclusion from the research.

As for people who practiced physical activities, those who performed at least 150 min/week of moderate physical activity or 75 min/week of vigorous physical activity were included. Regarding alcohol intake, up to 1 bottle of beer or 2 glasses of wine or 1 dose of spirits was considered moderate. Regarding eating habits, they met the recommendation when: consumed fruits and vegeTables on five or more days of the week; in natura or minimally processed foods 5 or more groups a day and ultra-processed when less than 5 groups a day (9,10).

For the statistical analysis, initially, a descriptive analysis of the data was carried out with the support of a statistician, containing estimates of mean, median, standard deviation, 25th and 75th percentiles, and interquartile range of component scores. The characteristics of the participants were analyzed descriptively with simple (n) and relative (%) frequencies. The association of chronic diseases was verified using the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test when applied. All tests were considered significant when p<0.05 and the analyzes were performed in the R 4.1.1 environment (R Core Team, 2021).

The research was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Health Sciences Sector/UFPR. CAAE number: 42695321.8.0000.0102 and Opinion CEP/SD-PB number: 4.618.359, on the date of: March 29, 2021. The study participants were informed about the purpose of the research and signed the Informed Consent Form ( TCLE), which informed the research objectives and ensured the participant's anonymity.

RESULTS

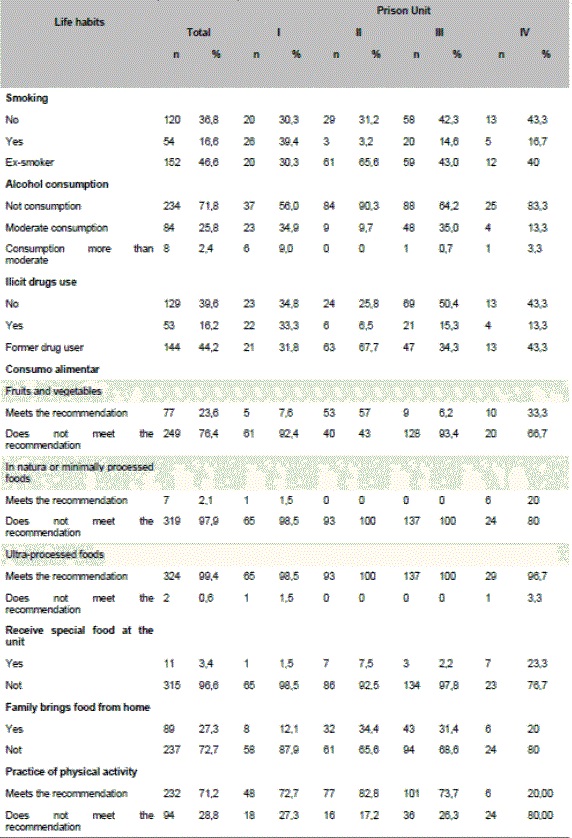

Regarding sociodemographic characteristics (Table 1), 296 were male (90.8%) and 30 were female (9.2%). Most of them were young people aged 18 to 29 years (174 - 53.4%), with only 7 (2.2%) people aged 60 years or older. The minimum age was 18, the maximum 73 and the mean 32.2 years (±10.09). With regard to marital status, singles predominated (141 - 43.3%), followed by married people (138 - 42.3%). Participants mostly had 1 to 3 children (191 - 58.6%) and most lived with three or more people at home before deprivation of liberty (262 - 80.4%).

Table 1: Sociodemographic characteristics of PDL. Foz do Iguaçu, 2021.

Source: the authors (2022)

Subtitle: n= number; %= percentage

As for the monthly family income prior to deprivation of liberty, 254 (77.9%) had an income of less than two minimum wages, of which 71 (21.8%) received less than one minimum wage.

Regarding schooling, less than nine years of study prevailed (182 - 55.8%), and women had a higher number of years of study than men, since 12 (40.0%) of them had from 9 to 12 years of study and 9 (30.0%) more than 12 years.

Most participants carried out activities in the penal unit (200 - 61.3%), with a greater proportion of females compared to males (24 - 80.0% versus 177 - 59.8%). The predominant activities were work (65 - 19.9%), study (53 - 16.3%), religious practices (42 - 12.9%) and other activities (40 - 12.3%).

When performing the self-assessment of health status on a 5-point scale, most reported as good (120 - 36.8%), regular (97 - 29.7%), very good (64 - 19.6%), bad (32 - 9.8%) and very bad (13 - 4.0%). Of the people who reported chronic diseases, 64.9% classified their health status as regular or good.

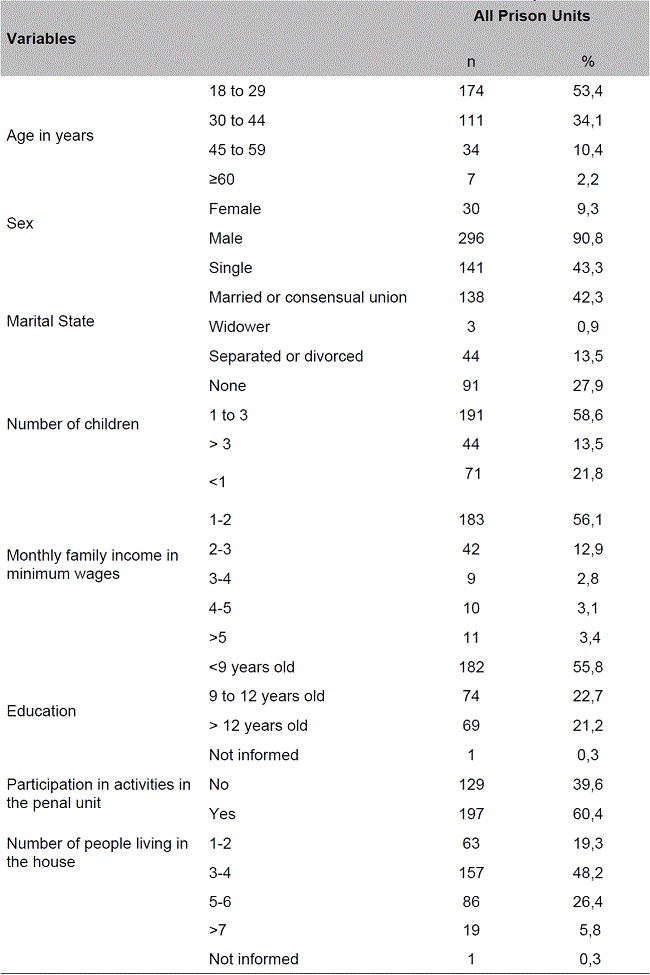

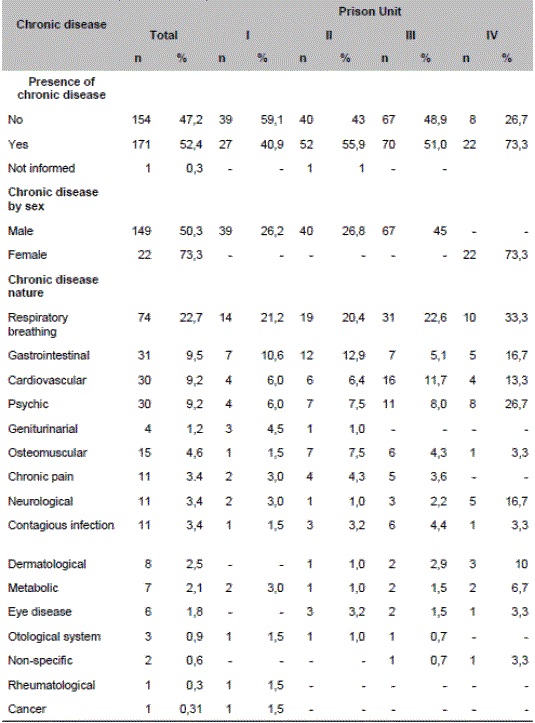

As for the presence of chronic diseases, in Table 2, it is observed that more than 50.0% of the people, in all penal units, had some chronic disease, except in the penal unit I whose proportion was 40.9%. The proportions of disease reports were higher in women compared to men (22 - 73.3% versus 149 - 50.3%). The diseases that prevailed in the self-reports were respiratory (74 - 22.7%); gastrointestinal (31 - 9.5); psychic (30 - 9.2%), cardiovascular (30 - 9.2%) and musculoskeletal (15 - 4.6%).

Table 2: Chronic diseases self-reported by the PDL of all prison and individual units. Foz do Iguaçu, 2021.

Source: the authors (2022)

Among the people who reported chronic non-communicable diseases, 70.1% reported using medications, and 18.1% used monotherapies, 3.2% from 2 to 3 medications and 4% more than 3 medications. In the general context of the participants, 115 (35.3%) reported continuous use of drug therapies and of these 65.3% had access to these medications in the penal unit.

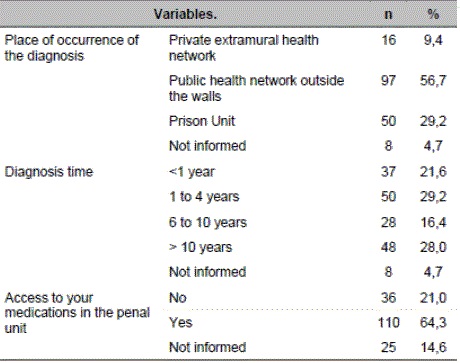

Regarding the place of diagnosis of self-reported diseases, Table 3 shows that half of the people received the diagnosis in the public extramural health network, between 1 and 4 years (29.5%).

Table 3: Place and time of diagnosis and access to PDL medications with some type of chronic disease in prison units. Foz do Iguaçu, 2021.

Source: the authors (2022)

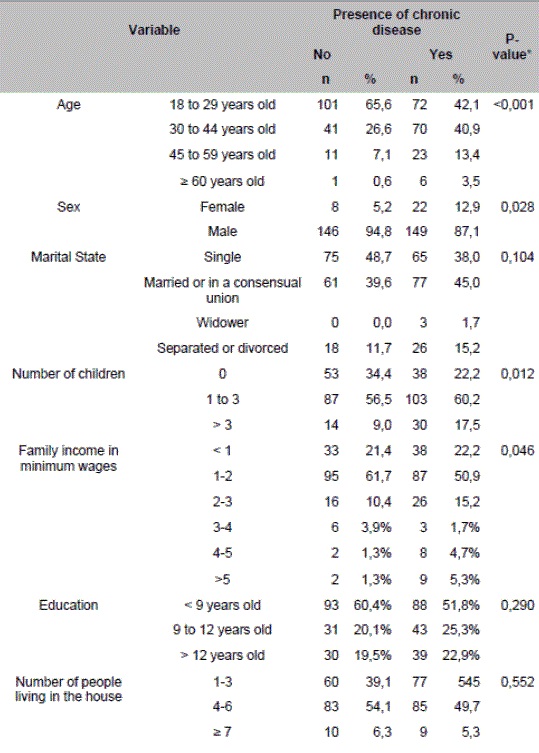

Table 4 shows that there was a statistically significant association between age group, sex, number of children and family income in relation to the proportion of occurrence of chronic diseases. People between 18 and 29 years old and 30 to 44 years old represent a total of 83% of people who have chronic diseases, while in the sex the male is predominant, of sick people 60.2% have 1 to 3 children and the family income is between 1 and 2 minimum wages.

Table 4: Sociodemographic variables of people in prison units and chronic disease. Foz do Iguaçu, 2021.

Source: the authors (2022)

In the general context of the penal units 16.6% (54) of the PDL declared themselves smokers and 46.6% (152) reported having smoked at some point in their lives. In relation to alcoholic beverages, 28.2% (92) reported previous use. The use of illicit drugs was reported by 16.2% (53) of the sample and 44.2% (144) reported former users. Among the people who declared a disease, 34.9% were smokers, 67% used alcohol prior to deprivation of liberty and 30.4% reported using drugs previously.

In relation to the eating habits learned from the PDL reports, the following predominate: rice and beans that are consumed 6 to 14 times a week for 313 (96%); breads and pasta for 305 (93.5%), meat for 111 (33.8%); vegeTables and greens for 142 (43.5%). Most do not consume fruits 210 (64.4%), canned foods, with preservatives 221 (67.8%), cookies, treats and candies 232 (71.2%) and or other foods 308 (94.5%).

Most of the PDL, 311 (96.6%) do not receive differentiated food in the unit, 237 (72.7%) depend exclusively on food provided in the penal unit. In relation to food, the fruit variables and if you have special food in the penal unit showed a significant difference in relation to chronic disease. In view of this aspect, it is noted that 40.9% of those who consume more fruits have some chronic disease and only 15 (3.4%) sick people consume some special food in the penal unit. Table 5 shows the life habits of people in the prison units.

As for physical activity, 71.1% (232) performed 150 minutes/week of moderate activities or 75 minutes/week of vigorous or mixed activities (moderate/vigorous. It is noteworthy that when observing only women, 80% (24) did not practice physical activities.

DISCUSSION

The sociodemographic characterization of the people deprived of liberty in this study showed no discrepancy in relation to the results identified in other investigations. The incarcerated population was predominantly male and young, in line with a study conducted in Chile with 141 PDL. It corroborates with research conducted with incarcerated women in the Brazilian northeast, in which 58.2% were between 18 and 29 years old and whose number of people over 60 years old reached 2%, and with a study carried out in Maranhão whose predominant age group was 26 to 35 years(11,12,13).

In relation to marital status, our study showed a predominance of singles, as well as other studies carried out with women from the Brazilian Northeast and men in Maranhão in a situation of deprivation of liberty (12,13).

The low education, less than 9 years of study, evidenced in this study, is above the 51% found in research with incarcerated women in the Brazilian northeast. However, when analyzing only the women in our sample, the indices are similar to those presented by the authors, and in a study with 122 PDL in Maranhão, in which 73% had incomplete elementary education. A study conducted with women in the state of São Paulo found an even lower level of education, because 61.3% had less than three years of study (12-14).

It is noteworthy that the PDL mostly exercised professions that did not require professional qualification, and, therefore, with low remuneration and educational level. Corroborating this finding, are the results of a study with women incarcerated in the Brazilian northeast (12).

Participation in activities in the penal unit, found in a São Paulo study with imprisoned women, showed that 95.8% and 88.5%, respectively, did not study or work, in contrast to our study that obtained high occupancy rates among female people in the sample. Horticulture project with people arrested in South Korea resulted in a decrease in depression, increased self-esteem and satisfaction with life, demonstrating the importance of including PDL in work activities (14,15).

When comparing the self-assessment of the health status of the PDL investigated with that found in the community, as for those that negatively evaluated their own health status (13.8 versus 4.8%, respectively, PDL and community) the index was much higher than that of the community. In a survey conducted with 199 PDL in Arizona, most considered their general health status as good (34.9%), regular (29.2%), which corroborates this analysis. It is emphasized, however, that prisons shelter people who are mostly socially marginalized, with health problems (untreated chronic diseases and mental illnesses) and risky lifestyles, such as high consumption of illicit drugs and alcohol. In addition, the overcrowded, unhealthy and violent prison environment can determine the well-being of PDL (10,16,17).

The report of morbidity found in this study for the general population was 50%, a rate similar to that found in a Chilean study, of 45%. However, among women, the rate reached 73.3%, similar to that found in a study with women incarcerated in Minas Gerais, Brazil of 77.4%. It should be noted that because they are mostly young, PDL should be associated with low rates of illness (11,18)

In line with our findings, a qualitative research carried out with eight women in a public chain in the state of Ceará, Brazil identified reports of cardiocirculatory and respiratory diseases and pain complaints. It also showed that the injuries arose or worsened after the arrest. PDL, in this perspective, tend to a high burden of diseases, with more deteriorated health than the general population, in particular, related to mental disorders, chronic non-communicable and infectious diseases (19,20).

It should be resumed that the health profile of PDL also results from deficits in living conditions prior to the seclusion regime expressed by social determinants such as poverty, low education and abuse in early childhood, as well as risk behaviors such as the use of drugs and alcohol, tattoos, physical aggression more frequent than those suffered by people in the general community, and may be potentiated by inadequate conditions in prison, such as overcrowding, inadequate structure, confinement, inadequate hygiene; and the lack of care when admitted to penal units (21).

The main cause of illness found in our research was related to the respiratory system, aligning the research with PDL that found rates of 66.6% of respiratory infections. The prevalent diseases in Chilean PDL research were Mental Disorders, Diseases of the Respiratory System, Circulatory and Digestive System, as in our study (11).

In contrast, a study with women arrested in the Brazilian northeast found high rates of sexually transmitted infections (51.02%) and arterial hypertension (46.493%), which does not corroborate our findings. A study with 271 women arrested in Canada found rates that are close to our research on respiratory diseases (22.7 versus 18%), and differed on infectious diseases (3.4% versus 19.0%) and the musculoskeletal system (4.6% versus 31.0%) (12,20).

A study conducted in New York, United States of America (USA) with 900 people arrested also found respiratory diseases (34.1%), followed by cardiovascular (17.4%) and sexually transmitted (STD; 16.1%); like our study, with low prevalence of infectious diseases, HIV (3.6%). In contrast, research with 199 PDL in Arizona had as self-reported conditions with higher prevalence hypertension (35.9%); high cholesterol (17.8%), arthritis (17.5%) and asthma (14.9%) (16,21).

The access to medications in a study conducted with PDL in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, showed that they understood that he was deficient, requiring the family to pay for the treatment, including medications of continuous use, which aligns the sample we studied, in which a large proportion reported not having access to their medications, despite the majority receiving them in the penal unit (22).

Physical activity with practice of 150 minutes/week of moderate activities or 75 minutes/week of vigorous or moderate/vigorous mixed activities was found in 71.17% of our sample, however absent in 80% of women, which corroborates community data (men 46.7% and women 32.4%). In the case of women, data from research carried out with women incarcerated in prisons in São Paulo, Brazil with rates of 70% of absence of physical activity (10,14,18)) are similar.

When comparing our findings with the community, PDL showed superior practice of physical activity (71.2 versus 39.0%). The importance of the practice of physical activity is emphasized, since a study with 199 PDL in Arizona found an index of 61.3% of overweight and obesity. It is emphasized that sedentary lifestyle, combined with overweight are risk factors for chronic non-communicable diseases (14,16).

In this study, smoking obtained lower rates than that found in other studies, which found rates of 80.6% in research with incarcerated women in Minas Gerais, Brazil and 60.3% also with female people in the Northeast, and in São Paulo with rates of 26.1%. In contrast to community data (9.8% versus 12.3%, respectively between males and females), the proportion found in our study was higher for PDL than for people in the community. Thus, the control measures implemented in Brazil in the last 20 years that have resulted in a significant decrease in the prevalence of smoking and tobacco-related diseases, are not effective within the prison institutions of the country (10,12,14,18).

The use of alcoholic beverages (44.37%) was similar to that found in a study in the northeast, as well as that of previous use of illicit drugs (41.7%) and a study in São Paulo with imprisoned women that found rates of 62.3% of previous use of illicit drugs and a study conducted in the United States of America that found 77.5% of history of use of illicit drugs (12,14).

The units of the triple border region seem to act as a protective factor regarding the consumption of alcohol, cigarettes and other drugs, as well as, in the sense of offering space for the practice of physical activity. However, a balanced diet could improve the quality of life of these people. Elements that are similar to the data from the study with PDL in Chile, regarding the protection against the consumption of alcohol, drugs and difficulty with food, and differ in terms of factors that could be improved such as smoking and physical activity (11).

Research conducted with 17 nurses in the United Kingdom identified as factors that can contribute to obesity and weight gain in prisons: the behavior of the prisoner with inadequate food choices and sedentary lifestyle. Systematic review and meta-regression showed a higher prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors among prisoners than in the general population, finding an average increase of 5.3 kilos during incarceration, especially soon after entering prison, with stabilization after two years(25.26).

It is resumed that in the community 34.3% of people consume fruits and vegeTables and 59.7% beans on five or more days of the week, higher, therefore, than the consumption of the PDL studied for fruits and vegeTables and lower than the consumption of beans and rice found in this research. Research conducted on menus of correctional systems in the Midwest of the USA revealed low supply of fruits and dietary fiber in male prisons and excessive calories and lack of vegeTables in female and male, as well as excessive supply of sodium (10.27).

It is pointed out, however, that the frequency of consumption of bread and pasta was high for the population studied, corroborating a cross-sectional study with 1,013 women prisoners in the state of São Paulo, Brazil, which found for 91.9% consumption of hot dog bread, sweet bread with margarine or butter, which is part of the group of ultra-processed foods daily. As for the intake of cookies and sweets, in contrast to this there was consumption of cookies with or without filling and sweets daily of 50.4%. The improvement in nutritional conditions and regulation of minimum feeding standards can reduce the burden of chronic health conditions related to it (27,28).

It should be resumed that according to the Prison Health Guide, people arrested should not leave prisons in worse conditions than the one they presented when they entered. Thus, the maintenance of healthy living habits and the control of chronic diseases are essential to guarantee the right to PDL health. It is noteworthy that cardiovascular diseases were the main causes of death among incarcerated and newly released in the USA and that 89% of deaths were related to chronic diseases(1,29,30).

Prisons need to be made up of health-promoting spaces, which provide PDL to improve their health and well-being conditions, especially because they are primarily social marginalized prior to imprisonment. The treatment of PDL in penal units is an opportunity for public health to promote health and protection to this population group, both in the prison scenario and in its readmission to the community. It is necessary to overcome health care with a pathogenic focus, expanding to a positive view of health, salutogenic, which reflects environmental, organizational and personal factors, in order to meet the specific needs of this population (17,20).

The limitations of this study are related to the fact that most studies that deal with prison health discuss it regarding infectious diseases and mental health, to the detriment of chronic diseases such as respiratory, cardiovascular, cancer, among others. The descriptive study is considered the limit of this investigation, because it presents a "portrait" of the health situation, especially the modifiable risk factors that can be potentially controlled, but without making inferences about the health behavior of the studied group.

CONCLUSION

It is concluded that the chronic illness in the prison population studied resembles the general population, as well as the risk factors, except for the consumption of illicit drugs, cigarettes and alcohol that were reduced with incarceration and related to physical activities that were higher than that found in the general population.

The feeding of prisoners is limited to that provided by the penal unit, whose menus prioritize caloric foods (carbohydrates), to the detriment of fruits, vegeTables and legumes. Changes in lifestyle related to food are limited in this sense, to the food available, with few possibilities of interventions.

The inclusion of PDL in labor and educational activities allows them to remain productive and help them maintain general well-being and satisfaction with life, despite imprisonment.

Estimating the sociodemographic characterization, health conditions and life habits of PDL allows us to understand the specific needs of this population group. It can contribute to the formulation of public policies aimed at their demands, and in particular, with health-promoting actions, through health education actions and structural changes in the prison context, with a view to improving their life and health. Aligning, in this sense, to person-centered care and care beyond the centered doctor.

This research can contribute to the visibility and reflection of the prison health theme, as well as to the formulation of health policies aimed at this specific population, in particular, highlighting the importance of health promotion actions. Therefore, modifiable risk factors can be potentially prevented and controlled through the planning and implementation of health promotion measures proposed by health professionals working in the prison system.

REFERENCIAS

1. World Health Organization (WHO). Prisons and health. WHO Regional Europa, 2014. [ Links ]

2. Giovanella L. (Org.). Políticas e Sistema de Saúde no Brasil. 2. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Fiocruz, 2012. [ Links ]

3. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Portaria nº 2.436, de 21de setembro de 2017. Aprova a Política Nacional de Atenção Básica, estabelecendo a revisão de diretrizes para a organização da Atenção Básica, no âmbito do Sistema Único de Saúde. Ministério da Saúde: 2017. [citado 2022 mar 22]; https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/gm/2017/prt2436_22_09_2017.html [ Links ]

4. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Portaria Interministerial nº 1, de 2 de janeiro de 2014. Institui a Política Nacional de Atenção Integralà Saúde das Pessoas Privadas de Liberdade no Sistema Prisional (PNAISP) no âmbito do Sistema Único de Saúde. Ministério da Saúde: 2001. [citado 2022 mar 22]; https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/gm/2014/pri0001_02_01_2014.html. [ Links ]

5. Brasil. Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil. Brasília: Senado Federal, 1988. [ Links ]

6. Agência Câmara de Notícias. Audiência pública da Comissão de Seguridade Social e Família: 2021. [citado 2022 mar 22]; Disponível em: https://www.camara.leg.br/noticias/809392-falta-de-informacoes-sobre-saude-de-presos-dificulta-controle-de-doencas-alertam-debatedores/. [ Links ]

7. Cuschieri S. The STROBE guidelines. Saudi J Anaesth. 2019. 3(Suppl 1): S31-S34. doi: 10.4103/sja.SJA_543_18. [ Links ]

8. Conselho Nacional de Justiça. Dados das inspeções nos estabelecimentos penais: 2020. [citado 2022 mar 22]. Disponível: http://www.cnj.jus.br/inspecao_penal/mapa.php. [ Links ]

9. Barroso WKS, et al. Diretrizes Brasileiras de Hipertensão Arterial. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2021; 116(3):516-658. doi: https://doi.org/10.36660/abc.20201238. [ Links ]

10. Brasil. Vigitel Brasil 2019: vigilância de fatores de risco e proteção para doenças crônicas por inquérito telefônico: estimativas sobre frequência e distribuição sociodemográfica de fatores de risco e proteção para doenças crônicas nas capitais dos 26 estados brasileiros e no Distrito Federal em 2019. Ministério da Saúde, 2020. [ Links ]

11. Osses-Paredes CY, Riquelme-Pereira N. Situación de salud de reclusos de un centro de cumplimiento penitenciario, Chile. Rev. esp. sanid. penit. 2013; [citado 2022 mar 20]; 15 (3): 98-104. Disponível em: https://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S1575-06202013000300003. [ Links ]

12. Medeiros MM, Santos AAP, Oliveira KRV, Silva JKAM, Silva NAS, Anunciação BMG. Panorama das condições de saúde de um presídio feminino do nordeste brasileiro. Rev. Pesqui. (Univ. Fed. Estado Rio J., Online). 2021; 13:1060-1067. doi: 10.9789/2175-5361.rpcfo.v13.9962. [ Links ]

13. Oliveira ECSS, Marinelli NP, Santos FJL, Gomes RNS, Neto NMG. Perfil epidemiológico dos internos de uma central de custódia de presos de justiça. Rev enferm UFPE. 2016; 10(9):3377-3383. doi: 10.5205/reuol.9571-83638-1-SM1009201624. [ Links ]

14. Audi CAF, Santiago SM, Garcia MG, Priscila A, Francisco MSB. Inquérito sobre condições de saúde de mulheres encarceradas. Saúde Debate. 2016; 40(109):112-124. doi: 10.1590/0103-1104201610909. [ Links ]

15. Lee A-Young, et al. Programa de terapia hortícola para saúde mental de presos: relato de caso. Pesquisa em medicina integrativa. 2021; 10(2):100495. doi: 10.1016/j.imr.2020.100495. [ Links ]

16. Trotter RT, Lininger MR, Camplain R, Fofanov VY, Camplain C, Baldwin JA. A Survey of Health Disparities, Social Determinants of Health, and Converging Morbidities in a County Jail: A Cultural-Ecological Assessment of Health Conditions in Jail Populations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2018; 15(11): 2500. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15112500. [ Links ]

17. Baybutt M, Chemlal K. Health-promoting prisons: theory to practice. Global Health Promotion. 2015; 23 (1): 66-74. doi: 10.1177/1757975915614182. [ Links ]

18. Aquino LCD, Laurindo CR, Silva MF, Leite ICG, Cruz DT. Mulheres encarceradas: relação entre autoavaliação do estado de saúde e experiências discriminatórias. Tempus, actas de saúde colet. 2021; 12(2), 125-143. doi: 10.18569/tempus.v12i2.2832. [ Links ]

19. Araújo MM, Moreira AS, Cavalcante EGR, Damasceno SS, Oliveira DR, Cruz RSBLC. Assistência à saúde de mulheres encarceradas: análise com base na Teoria das Necessidades Humanas Básicas. Esc. Anna Nery Rev. 2020; 24(3): e20190303. doi: 10.1590/2177-9465-ean-2019-0303. [ Links ]

20. Nolan A, Stewart LA. Chronic Health Conditions Among Incoming Canadian Federally Sentenced Women. Journal of Correctional Health Care. 2017; 23(1): 93-103. doi: 10.1177/1078345816685707. [ Links ]

21. Bai JR, Befus M, Mukherjee DV, Lowy FD, Larson EL. Prevalence and Predictors of Chronic Health Conditions of Inmates Newly Admitted to Maximum Security Prisons. J Correct Health Care. 2015; 21(3): 255-264. doi:10.1177/1078345815587510. [ Links ]

22. Minayo MCS, Ribeiro AP. Condições de saúde dos presos do estado do Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. Ciência e Saúde Coletiva. 2016; 21(7):2031-2040. doi: 10.1590/1413-81232015217.08552016. [ Links ]

23. Ainsworth B, Haskell WL, Herrmann SD, Meckes N, Bassett DR, Catrine Tudor-Locke C, et al. 2011 compendium of physical activities: A second update of codes and MET values. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2011; 43(8):1575-1581. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31821ece12. [ Links ]

24. Rowell-CunsoloTL, Sampong SA, Befus M, Mukherjee DV, Larson EL.Predictors of Illicit Drug Use Among Prisoners. Subst Use Misuse. 2016; 51(2): 261-267. doi:10.3109/10826084.2015.1082594. [ Links ]

25. Choudhry K, Armstrong D, Dregan A. Nurses's Perceptions of Weight Gain and Obesity in the Prison Environment. Journal of Correctional Health Care. 2017; 23(2) 173-183. doi: 10.1177/1078345817699830. [ Links ]

26. Bondolfi C, Taffe P, Augsburger A, Jaques C, Malebranche M, Clair C, Bondenmann P. Impacto do encarceramento nos fatores de risco para doenças cardiovasculares: uma revisão sistemática e meta-regressão na alteração do peso e do IMC. BMJ Open. 2020; 10(10): e039278. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039278. [ Links ]

27. Holliday MK, Richardson KM. Nutrition in Midwestern State Department of Corrections Prisons: A Comparison of Nutritional Offerings With Commonly Utilized Nutritional Standards. Journal of Correctional Health Care. 2021; 27(3):154-160. doi: 10.1089/jchc.19.08.0067. [ Links ]

28. Audi CAF, Santiago SM, Andrade MGG, Assumpção D, Francisco PMSB, Segall-Corrêa AM, Pérez-Escamilla R. Consumo de alimentos ultraprocessados entre presidiárias de um presidio feminino em São Paulo, Brasil. Rev Esp Sanid Penit. [citado 2022 mar 22] 2018; 20(3): 88-96. Disponível em: https://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1575-06202018000300087. [ Links ]

29. Wang EA, Redmond N, Himmelfarb CRD, Pettit B, Stern M, Chen J, Shero S, Iturriaga E, Sorlie P,Roux AVD, Cardiovascular Disease in Incarcerated Populations.J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017; 69(24): 2967-2976. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.04.040. [ Links ]

30. Loeb SJ, McGhan G, Hollenbeak CS. Who Wants to Die in Here? Perspectives of Prisoners with Chronic Conditions. J HospPalliatNurs. 2014; 16(3): 173-181. doi: 10.1097/NJH.0000000000000044. [ Links ]

Received: February 28, 2023; Accepted: July 08, 2023

texto en

texto en