INTRODUCTION

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a degenerative and chronic disease of central nervous system with an autoimmune origin, which affects the brain and spinal cord. Immune system attacks the myelin sheaths that surround the neurons, damaging them and giving rise to inflammation. This causes the nervous impulses that circulate through the neurons to be obstructed or directly interrupted, with the consequent effects on the organism. Currently the cause of this disease is unknown, but studies indicate that its appearance may have a double origin, a genetic component stimulated by environmental factors1,2.

Symptoms of multiple sclerosis vary depending on the location, extent, severity and number of lesions. The most common are fatigue, intellectual deterioration, tremor and dystonia. There are several forms of evolution3:

Relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) follows a relapsing-remitting course defined by acute exacerbations of which there is usually an incomplete recovery, with periods of relative clinical stability. 65-80% of patients initially have RRMS, with a frequency of 1-2 outbreaks per year and a disability that increases progressively.

Primary-progressive multiple sclerosis (PPMS) is typical of patients with progressive decrease in neurological function from the onset of the disease, describing symptoms of progressive myelopathy or progressive cerebellar syndrome.

Secondarily-progressive multiple sclerosis (SPMS) is the one that many patients who initially have RRMS tend to develop. It is defined by a gradual decrease in neurological functioning after an initial relapse course.

Clinically isolated syndrome (ACS) is the initial presentation of a patient with clinical symptoms typical of demyelinating event. A patient is classified as ACS when there is clinical evidence of a single exacerbation and the magnetic resonance does not fully meet the criteria for RRMS (does not meet dissemination over time).

At the moment there is no cure for MS. The current treatments are aimed at slowing down their natural evolution with disease-modifying drugs (DMD) for multiple sclerosis or at alleviating symptoms to maintain a better quality of life. DMD4 group consists of IFN β1a (Avonex®, Rebif®), IFN β1b (Betaferon®), glatiramer acetate (Copaxone®), mitoxantrone (Novantrone®), natalizumab (Tysabri®), fingolimod (Gilenya®), dimethyl fumarate (Tecfidera®), teriflunomide (Aubagio®), cladribine (Mavenclad®), ocrelizumab (Ocrevus®) and alemtuzumab (Lemtrada®).

WHO defines adherence as compliance (taking the medication according to the prescribed pattern in terms of dose and frequency) and the persistence thereof from the beginning to the discontinuation of the indicated therapy, also representing a factor contributing to the efficacy of treatments in chronic diseases5. Therefore, for the optimization of disease-modifying therapy (MST) for MS, strict adherence to treatment is necessary. However, although these drugs have been shown to decrease the number of MS relapses, the reality is that in this type of patient such drug adherence is not optimal. Some of the factors related to non-adherence may be the chronicity of the treatments, the adverse effects, the intolerances or the non-perception of an immediate benefit6.

On the other hand, most patients with MS take medication concomitantly to treat comorbidities or symptoms that are presented with the progress of the disease, such as depression, fatigue, gail changes and sleeping, spasticity or bladder dysfunction7.

Main objective of this review is to measure the indirect adherence of patients with multiple sclerosis to their pharmacological treatments, comparing medication for this disease with that of the other concomitant treatments that have been prescribed chronically.

METHODS

Cross-sectional, descriptive study on November 2018, at Pharmacy External Outpatient Unit of a secondary hospital at Valencian Community with a reference population of approximately 160,000 inhabitants. Study population are all those patients diagnosed with MS in its different variants, who are being treated with DMD dispensed by hospital pharmacy staff. As an inclusion criteria, it has been established that patients were in treatment for a minimum of six months prior to the study8, so those who did not comply were not included, either due to change of treatment or because of an interruption of treatment for any reason.

The electronic clinical records were consulted for the collection of data, reviewing the pharmacotherapeutic history of each patient on Abucasis® program, the application for outpatient dispensing by MDIS® for hospital dispensing DMD drugs and pharmacotherapeutic history of pharmacy dispensing registered from primary care. The anonymized database has been made using an Excel® spreadsheet.

The evaluated variable has been the percentage of adherence of patients to their medication, both the one collected at Hospital Pharmacy Department and at their Pharmacy office, which has been measured as the ratio between the doses of prescribed drugs and those dispensed; considering adherent to all patients with a percentage equal to or higher than 80%6.

To calculate the percentage of adherence for each drug, the medication collections made on May 2018, and the last collection before November 2018 have been measured. In this way, it has been known the number of drugs that each patient has for 6 months and, comparing it with the doses that should have, the percentage of adherence has been calculated by the following formula:

Prescribed doses have been defined with the average theoretical number of administrations per day according to the personalized medical prescriptions for each drug and patient, multiplying them by the follow-up time. The doses of dispensed drugs have been defined as the total number of units dispensed.

In case of interruption or change of medical treatment during the proposed period, the patient has been excluded from the study.

For the average calculation, adherences greater than 100% (data obtained by having set a specific cut-off date and not a next dispensation date) have been considered as 100% of adherence. The reason is that the establishment of an end date causes that there is a surplus of medication that exceeds 100% when performing adherence calculations.

In the statistical analysis, categorical data have been expressed as absolute frequency and percentage, and continuous data as average and standard deviation (SD). Statistical significance has been established at p<0.05.

RESULTS

The total number of patients diagnosed with MS and on treatment from the Pharmacy External Outpatient Unit during the study period was 94 patients, of whom 86 were included in the study (63.8% are women) with an average age of 44.1±11.8 years. 8 patients were excluded because they did not comply with a minimum of 6 months of treatment at the time of the study.

The average exposure time to drugs was 198.7±27.9 days at the time of the cross section, during which the overall adherence to all prescribed drugs was 95.0±15.4%.

Establishing a difference between adherence to the treatment of multiple sclerosis and adherence to the rest of the chronic concomitant medication, a result of 98.1±6.6% and 92.8±19.5%, respectively, was obtained.

Regarding the adherence to DMD there are slight differences depending on the route of administration (table 1).

Table 1. Adherence to the treatment of MS according to administration route

SD: standard deviation; n: number of patients; IM: intramuscular; SC: subcutaneous.

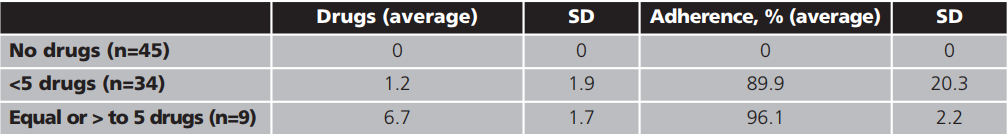

On the other hand, to evaluate the variability in adherence to the rest of medication from primary care, we have stratified according to the number of prescribed drugs, being polymedicated patients (greater or equal to 5 drugs), patients taking less than 5 drugs or patients without additional drugs, as shown in table 2.

DISCUSSION

In the PS of our hospital there are 94 MS patients who come to collect medication, but 8 of them do not comply the inclusion criteria, so they have not been part of the study. The reasons have been that 3 patients did not comply the minimum of 6 months of treatment because they were initiating it, 2 had changed their medication, 2 had interrupted the treatment by medical order and 1 patient had died in the previous weeks.

The obtained data show a higher prevalence of MS in the female population of the study, as the literature indicates, since MS is a more frequent disease in women than in men (except in the primary-progressive MS forms, with an equal or greater prevalence in males)9. On the other hand, the obtained data also show that the age of most patients with MS is between the third and fourth decade of life.

Some studies have evaluated the therapeutic adherence to the treatment of MS. An observational and prospective study obtained a 75% adherence measured through patient interview10. However, it is not comparable to this study because, instead of doing an average calculation, it categorized patients as adherent or non-adherent. Other studies more like the present, although the main variable was measuring treatment discontinuations, obtained results between 72 and 88%7,11,12of adherence through an evaluation of drug dispensing records. In the result of the adherence calculation measured by the drug dispensing records, it must be borne in mind that the excess medication of the patient is not considered, the actual dosage compliance is unknown, and the adherence tends to be overestimated. Therefore, it is necessary to consider the possibility that the "real" adherence to MST is lower than what was observed in this study, and that we cannot detect it only through the electronic records of dispensations.

Regarding the route of administration of DMD for MS, the one with the least adherence is the subcutaneous route, which coincides with being the one that presents a narrower or more complex period between injections. This can lead to forgetfulness of administration or rejection due to adverse effects. The intramuscular route shares many aspects and adverse effects with the subcutaneous route but is favoured when presenting a weekly or biweekly administration.

Patients who take oral DMD are the most adherent; the simplification of the dosage regimen to one or two doses per day may be the main cause. In addition, oral administration promotes greater comfort of administration, less psychological impact and, thus, a reduction in the number of missed medications. According to other studies, when patients with RRMS were treated following patient preferences compared to current prescribing practices, health outcomes were improved13,14.

Regarding the additional medication to the treatment of MS, there are some patients who present an especially low adherence, while their adherence to the DMD is optimal. Approximately 50% of these primary care drugs are antidepressants and hypnotics, which may explain the low adherence of patients.

Sometimes, adherence to these drugs is lower than the treatment itself for MS because patients do not perceive enough improvement or because they believe that they are less important for being dispensed at the pharmacy. This can cause an occasional drugs administration, motivated by the situation or mental state of each patient, with administration only in case of need, although on the part of primary care it is prescribed chronically.

Finally, for further analysis of the concomitant treatment, the registered adherence has been differentiated between: polymedicated patients (equal or >5 medications), non-polymedicated (<5 drugs) and without additional treatment. The inequality detected between the first two (96.1±2.2% vs. 89.9 ± 20.3%) could be due to the fact that the polymedicated patients are more aware in the drugs administration because they are multi-pathological and with a more established routine of administration, given the high number of prescribed drugs. However, 66.7% of polymedicated patients are around 50 years of age and 33.3% are elderly people who may be in charge of family members and/or caregivers, which could influence their greater perception of the situation and, therefore, in its greater adhesion.

The limitations of the study have already been reflected in this discussion. On the one hand, the small number of patients and the limitation to only six months of treatment, since these treatments have prescriptions of many years of duration. On the other hand, the measure of adherence with a single indirect method, since, being a cross-sectional study, no interviews have been carried out with patients to supplement with adherence data reported by patients, being this a possible continuation of the study.

CONCLUSION

The results obtained are a cause for reflection due to the potential clinical repercussion that the lack of adherence can cause. They should motivate the hospital pharmacist and the community pharmacist to carry out joint pharmaceutical care strategies through the development of actions to improve adherence to medication. Therefore, in addition to control the drug dispensation of DMD, the pharmacist must perform a comprehensive approach and focus attention on the treatment of possible comorbidities or symptomatic treatments.