Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Pharmacy Practice (Granada)

versión On-line ISSN 1886-3655versión impresa ISSN 1885-642X

Pharmacy Pract (Granada) vol.4 no.2 Redondela abr./jun. 2006

|

Original research |

Screening for osteoporosis among post-menopausal women in community pharmacy

Detección de osteoporosis en mujeres posmenopáusicas en farmacia comunitaria

Damià BARRIS BLUNDELL, Carmen RODRÍGUEZ ZARZUELO, Belén SABIO SÁNCHEZ, José Luis GUTIÉRREZ ÁLVAREZ,

Elena NAVARRO VISA,Óscar MUÑOZ VALDÉS, Belén GARRIDO JIMÉNEZ, Rocío SÁNCHEZ GÓMEZ.

|

ABSTRACT Objectives: To identify postmenopausal women with risk of osteoporosis

through quantitative ultrasound imaging (QUI) and to value the medical

intervention after the determination of the bone mineral density (BMD). Key words: Osteoporosis. Osteopenia. Mass screening. Ultrasonography. Spain. |

RESUMEN Objetivos: Identificar mujeres posmenopáusicas con riesgo de osteoporosis

mediante ultrasonografía ósea cuantitativa y valorar la

intervención médica tras la determinación de la densidad

mineral ósea. Palabras clave: Osteoporosis. Osteopenia. Cribado. Ultrasonografía. España. |

Damià BARRIS BLUNDELL. BSc (Pharm). Community pharmacist at Benalmadena

Malaga (Spain).

Carmen RODRÍGUEZ ZARZUELO. BSc (Pharm). Community pharmacist at Benalmadena

Malaga (Spain).

Belén SABIO SÁNCHEZ. BSc (Pharm). Community pharmacist at Benalmadena

Malaga (Spain).

José Luis GUTIÉRREZ ÁLVAREZ. BSc (Pharm). Community pharmacist

at Benalmadena Malaga (Spain).

Elena NAVARRO VISA. BSc (Pharm). Community pharmacist at Benalmadena Malaga

(Spain).

Oscar MUÑOZ VALDÉS. BSc (Pharm). Community pharmacist at Benalmadena

Malaga (Spain).

Belén GARRIDO JIMÉNEZ. BSc (Pharm). Community pharmacist at Benalmadena

Malaga (Spain).

Rocío SÁNCHEZ GÓMEZ. BSc (Pharm). Community pharmacist

at Benalmadena Malaga (Spain).

INTRODUCTION

Osteoporosis is a systemic disease of the skeleton, characterised by low bone mass and alterations in the micro-architecture of the bone tissue that lead to an increase in brittleness with the ensuing predisposition to bone fractures.1 In 1994 the World Health Organisation (WHO) established diagnostic criteria based on the results of bone densitometry results obtained, in which osteoporosis is considered to exist with a reduction in the mineral bone density (MBD) of 2.5 standard deviations below the mean of the bone mass peak.2 Based on this commonly-accepted criterion, it is estimated that some 2 million women3 suffer from osteoporosis in Spain.

Given the progressive aging of our society, osteoporosis is an emerging disease that has increased in prevalence over the past few years. The most important consequence is the morbid-mortality associated to the fractures, especially among the elderly, which has a great effect on the quality of life of patients and social and health costs.4,5

Since it is a silent disease with no symptoms prior to the fracture, it is well worth putting into practice strategies aimed at preventing fractures caused by osteoporosis. For this reason, the community pharmacy role may be significant in preventing this disease. Despite the fact that community pharmacies are a health agency that is accessible for both the health and sick population, with proven capacity to performing screenings6, in Spain there is very little literature that analyses the participation of community pharmacies in strategies for preventing the risk of osteoporosis.7,8

The quantification of the MBD, determined by the quotient between the bone mass, measured in grams, multiplied by the surface area, measured in square centimetres, has become an essential element in evaluating patients at risk of suffering from osteoporosis, since it is one of the most useful factors in predicting the risk of fractures due to brittleness9 Bone densitometry by dual X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) is currently regarded as the most effective test or method for diagnosing osteoporosis.10 The prediction of the risk of fractures is greater when the MBD is measured directly in the bones that are most often affected (vertebral column and hip). However, technically speaking it is easier to measure the peripheral bones. Among the peripheral methods for measuring MBD, quantitative ultrasound imaging (QUI) has been associated, both in cross-over and prospect studies, with the prevalence and risk of fractures respectively, and provides an indication of the fracture risk, irrespective of the MBD, in particular in the case of hip fractures. It is currently proposed as a fast, economic, radiation-free alternative for evaluating the bone mass.11,12

Benefiting from these advantages, the present study was proposed in a community

pharmacy, with the following most important objectives:

To identify post-menopausal women at risk of suffering osteoporosis by QUI.

To evaluate the medical intervention after determining the MBD.

To ascertain the degree of patient satisfaction in relation to the new prevention

service provided.

METHODS

A cross-sectional, descriptive study conducted in a community pharmacy through the selection of post-menopausal women aged over 50, who visited the pharmacy during the month of June 2005. The exclusion criteria applied were being treated with calcium, vitamin D, substitutive hormonal therapy, raloxifen, calcitonin or biphosphonates.

All patients who agreed to participate in the study were subjected to a bone ultrasound analysis in the right heel bone with the Sahara (Hologic) device. This densitometer calculates MBD based on the ultrasound parameters measured: sound speed, ultrasound attenuation and quantitative ultrasound index. The WHO criteria were applied, classifying patients with MBD with a standard deviation of over 2.5 lower than the average for a young adult (T-Score < -2.5) as osteoporotic and patients with a T-Score of between -1 and -2.5 as osteopenic.

All participants were given 5 questionnaires or rating scales that made it possible to evaluate the individual risk of low MBD: National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF), Osteoporosis Risk Assessment Instrument (ORAI), Age Body Size No Estrogen (ABONE), Osteoporosis Self-Assessment Tool for Asians (OSTA) and a scale arising from the data of the Californian study Study of Osteoporotic Fractures (SOFSURF).

To ascertain patient satisfaction we prepared a questionnaire consisting of 3 closed questions to be responded to with an X in a scale rated from 1 to 5.

A descriptive analysis of the data was performed with the computer programme G-Stat, giving mean values, absolute frequencies, relative frequencies in percentages, minimums and maximums, standard deviation, regression spans, contingency tables and statistic significance (p<0.05) with the Chi square test.

RESULTS

Of the 100 women participating in the screening, 11 (11.0%) showed a risk of developing osteoporosis and 61 (61.0%) a risk of developing osteopenia. The average age of the 11 women with a risk of developing osteoporosis was 65.5 years, whereas the average age of the women with a risk of developing osteopenia was 64.6 years. Table 1 shows the main characteristics of the 100 participants.

18.5% of women with a body mass index (BMI) < 30 showed a risk of developing osteoporosis and 63.0%, osteopenia. Table 2 shows the different frequencies of the MBD alterations, depending on the BMI.

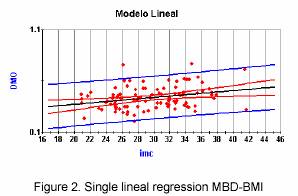

Figures 1 and 2 show the regression spans estimated by square minimums (relation between the MBD-age and MBD-BMI variables). Furthermore, the prediction axis consisting of prediction curves with a prediction of under 95% for mean values and prediction curves with a prediction of 95% for individual values.

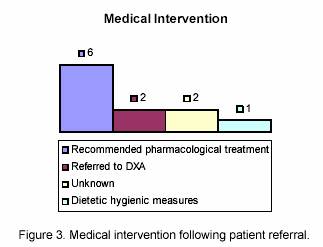

Medical intervention in the 11 patients with a risk of developing osteoporosis who advised to visit their physician is shown in figure 3, where it can be observed that in 6 patients the family physician recommended pharmacological treatment.

The questionnaire was completed by 87% of participants. 64.4% of those surveyed considered that the explanation given by the pharmacist on the test results was excellent and 29.9% considered it very good. Professional treatment was rated excellent by 74.7% of the women and 20.7% rated it as very good. The convenience of the pharmacy preparing a report for the physician on the test results was evaluated with an average score of 4.5, the explanation given by the pharmacist on the test results obtained a score of 4.6 and the treatment of patients by the pharmacist, 4.7.

The results after applying the different questionnaires or scales for measuring the risk of low MBD are shown in Table 3.

The mean MBD value of the women, depending on whether or not they met the criteria of the different scales for evaluating the risk of low MBD is shown in table 4.

In describing the association between the age>70 years and BMI <25 variables with the risk of osteoporosis (T-Score <-2.5) contingency tables and Chi square test were used. No statistically significant relation was found between the BMI<25 variable and the risk of osteoporosis (p=0.918) and neither was any statistically-significant relation found between the age>70 years variable and the risk of osteoporosis (p=0.776).

Also, when the Chi square test was applied among the risk of bone alterations (T-Score <-1.0) and the age>70 years and BMI<25 variables, a statistically significant relation was obtained between BMI<25 and the risk of bone alterations (p=0.0073). No significant relation was found for the age>70 years variable (p=0.743).

DISCUSSION

In the document Consenso sobre Atención Farmacéutica (Consensus

on Pharmaceutical Care) published by the Ministry of Health and Consumer Affairs13,

pharmaceutical care is defined as the active participation of the pharmacist

in attending patients in the dispensing and follow-up of a pharmacotherapeutic

treatment, thereby cooperating with the physician and other healthcare professionals

for the purpose of achieving results that will improve the quality of life for

patients. It also entails involving pharmacists in activities that will promote

good health and prevent diseases. The latter is related to the integration

of community pharmacists into the development of prevention strategies through

screening. Taking into account the field of activity open to community pharmacies

in screening, the present study is intended to contribute an innovative practice

in an attempt to benefit from new technologies in combating osteoporosis as

a preventive activity. The main reasons why QUI was selected as the MBD measuring

technique were as follows:

Its use as a screening tool and for evaluating the risk of osteoporotic fractures

is supported by the International Society for Clinical Densitometry.14

It is a useful tool in predicting the risk of fractures among women with low

MBD and can therefore be used in primary care to refer patients to their physicians

for more thorough assessment on osteoporosis.15

It is a method that uses small-sized equipment without the need for employing

specialist staff, in addition to being an easy technique to perform.16,17

The QUI screening strategy can be converted into an option for situations

in which the osteoporosis diagnosis is defective, due to the difficulties of

gaining access to DXA equipment.18

The determining of MBD in the heel bone will be of great value if it leads to positive actions in influencing the risk of developing osteoporosis. For this reason, it is very important for medical staff to offer sufficient cooperation in screening performed on this pathology and for community pharmacies to be accepted as part of the multidisciplinary team dealing with the patient. If in addition to the results given in figure 3, we consider that 31 (50.8%) women with a risk of developing osteopenia consulted their physicians on the MBD determination made in the pharmacy and 21 (34.4%) received pharmacological treatment, it can be assumed that this new service is well accepted by physicians, who are willing to take clinical decisions after receiving this information. The reason for the low number of patients referred to DXA may lie in the difficulty experienced by primary care physicians in accessing the most important diagnosis technique, namely DXA.19,20 This situation appears to be in line with the data shown by studies demonstrating how difficult it is to use the DXA technique in the primary care area.5 For example, in Andalusia, only 5-10% of physicians surveyed were able to request densitometries. In another study performed in primary care centres all over Spain21 it is affirmed that the diagnostic criteria most often used in women visiting the primary care centres suspected as having developed osteoporosis are the case history, risk factors and conventional radiology. MBD is used in 32% of cases when diagnosing osteoporosis in primary care. Taking into account this situation, it seems only logical to expect a reduction in the number of patients for whom the DXA technique is prescribed.

The main objective of the rating scales in evaluating the risk of low MBD is to select the women prior to performing the densitometry, thereby optimising the use of this test. These scales provide information only on the risk of a low MBD without evaluating the individual risks of fractures.

Although the criterion for referral to QUI used in the present study was post-menopausal

women aged 50 years without being treated with calcium, vitamin D, substitutive

hormonal therapy, raloxifen, calcitonin or biphosphonates, five rating scales

for evaluating the risk of low MBD have been used in the women selected (NOF,

ORAI, ABONE, OSTA and SOFSURF) with the objective of describing the results

that would have been obtained by applying these questionnaires (tables 3 and

4). Such scales may easily be applied in daily practice in community pharmacies

for screening high-risk patients, but without forgetting their main limitation;

they are instruments that relate the risk factor with the reduction in the bone

mass. The low bone mass risk factors do not furnish any information on the risk

of fracture in the patient after determining the MBD.22 Different prospective

studies have shown that although MBD is an important predictor of bone fractures,

other risk factors also exist that have been shown to have equal or greater

association with the appearance of fractures than the presence of low bone mass.23

Both the skeletal risk factors (bone hardness and resistance) and those related

to falls (traumatism and force of impact) interact in a complex, synergic manner.24

The fracture risk factors are related to the risk of falls, type of traumatism

and force of the impact, and the hardness and resistance of the bone. In this

regard, we propose the following practical questionnaire which consists of 15

questions22:

Did you have your last period before the age of 45? (History of early menopause).

Did you have your ovaries removed before the age of 50? (Ooforectomy).

Have you ever broken a bone? (Previous history of factures).

Have you ever been treated with cortisone (or derivatives thereof) orally

for more than 6 months, at a dose of more than 7.5 mg/day)? (Cortisone treatment).

Do you weigh less than 55 kg? (Weight < 55 kg).

Do you have any relatives who suffer from osteoporosis or have had a bone

fracture (hip, column, wrist)? (Family history of osteoporosis).

Have you been menopausal for more than 10 years (no period)? (Menopause >

10 years).

Have you missed any periods during a term of over one year since the onset

of your menstruation cycle and before the menopause? (Previous history of amenorrhoea).

Since your youth, has your diet been lacking in calcium (milk and derivatives)?

(Diet lacking in calcium).

Do you consume alcohol regularly? (Alcohol intake).

Do you smoke more than 10 cigarettes a day? (Smoking habit).

Do you practice little physical exercise and lead a sedentary life (Many hours

spent sitting down or bedridden)? (Sedentary life).

Are you predisposed to falls (with or without fractures)? (Predisposed to

falls).

Do you have problems with your eyesight, even though you wear spectacles?

(Eyesight problems).

Do you suffer from any symptom of dementia? (Dementia symptoms).

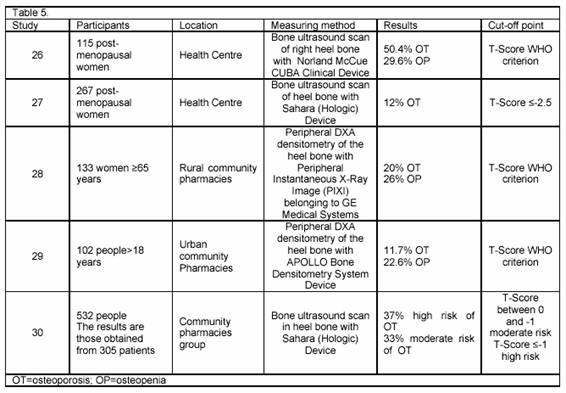

Table 5 shows different studies using peripheral densitometries to determine the risk of osteoporosis. The studies performed in community pharmacies share the same conclusions on the fundamental role of the pharmacist in community programmes for osteoporosis screening and the high level of cooperation provided by medical professionals.27-29

CONCLUSIONS

Quantitative ultrasound imaging is a useful tool in community pharmacies for screening osteoporosis and may constitute a new channel of integration into healthcare assistance.

With respect to taking future action aimed at tackling the problem of osteoporosis

in our community pharmacy, the following objectives have been defined:

Extending the osteoporosis screening activity to men.

Evaluating therapeutic compliance among patients with osteoporosis30

for the purpose of planning interventions at a later date that will improve

matters with respect to following treatment, if necessary.

Include an evaluation of the quality of life from the health standpoint in

the process of pharmacotherapeutic follow-up of osteoporosis treatments.31,32

|

References |

1. NIH Consensus Development Panel of Osteoporosis Prevention, Diagnosis, and Therapy. Osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis and therapy. JAMA 2001; 285: 785-795. [ Links ]

2. Orozco P. Actualización en el abordaje y tratamiento de la osteoporosis 2001. (2001 Update in combating and treating osteoporosis). Inf Ter Sist Nac Salud 2001; 25:117-141. [ Links ]

3. Díez-Curiel M, García JJ, Carrasco JL, Honorato J, Pérez R, Rapado A, et al. Prevalencia de osteoporosis determinada por densitometría en la población femenina española. Med Clin (Barc) 2001; 116: 86-88. [ Links ]

4. Zwart M, Fradera M, Solanas P, González C, Adalid C. Abordaje de la osteoporosis en un centro de atención primaria. Aten Primaria 2004; 33(4): 183-7. [ Links ]

5. Aragonès R, Orozco P, Grupo de Osteoporosis de la Societat Catalana de Medicina Familiar i Comunitària. Abordaje de la osteoporosis en la atención primaria en España (estudio ABOPAP-2000). Aten Primaria 2002; 30(6): 350-356. [ Links ]

6. Tuneu L, Fernández-Llimós F. Cribados desde la farmacia comunitaria. (Screening in community pharmacies) Aula de la farmacia 2005; 17(2): 8-16. [ Links ]

7. Barris D, Gutiérrez JL, Sabio B, Garrido B, Muñoz O, Navarro E. Detección del riesgo de osteoporosis en mujeres posmenopáusicas en una farmacia comunitaria. Pharmaceutical Care España 2005; 7 (Especial IV Congreso Nacional de Atención Farmacéutica): 105. [ Links ]

8. Atozqui J, Pío B. Campaña de sensibilización y de detección precoz de la osteoporosis en la farmacia comunitaria. Pharmaceutical Care España 2005; 7 (Especial IV Congreso Nacional de Atención Farmacéutica):116. [ Links ]

9. Moreno MC, Centelles F, Novell E. Indicación de densitometría ósea en mujeres mayores de 40 años. Aten Primaria 2005; 35(5): 253-257. [ Links ]

10. Muñoz-Torres M, De la Higuera M, Fernández-García D, Alonso G, Reyes R. Densitometría ósea: indicaciones e interpretación. Endocrinol Nutr 2005; 52(5): 224-227. [ Links ]

11. Rodríguez A, Díaz-Miguel C, Vázquez M, Martín G, Beltrán J. Medición ultrasónica del hueso en mujeres sanas y factores relacionados con la masa ósea. Med Clin (Barc) 1999; 113(8): 285-289. [ Links ]

12. Frost ML, Blake GM, Fogelman I. Quantitative ultrasound and bone mineral density are equally strongly associated with risk factors for osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res 2001; 16: 406-416. [ Links ]

13. Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo. Consenso sobre Atención Farmacéutica. Madrid, 2000. [ Links ]

14. Leib ES, Lewiecki EM, Binkley N, Hamdy RC. Oficial position of the Internacional Society of Clinical Densitometry. J Clin Densitom 2004; 7: 1-5. [ Links ]

15. Stewart A, Reid DM. Quantitative ultrasound or clinical risk factors – Wich best identifies women at risk of osteoporosis. Br J Radiol 2000; 73: 165-171. [ Links ]

16. Sosa M et al. Prevalencia de osteoporosis en la población española por ultrasonografía de calcáneo en función del criterio diagnóstico utilizado. Datos del estudio GIUMO. Rev Clin Esp 2003; 203(7): 329-33. [ Links ]

17. Frost ML, Blake GM, Fogelman I. Quantitative ultrasound and bone mineral density are equally strongly associated with risk factors for osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res 2001; 16: 406-416. [ Links ]

18. Marín F, López-Bastida J, Díez-pérez A, Sacristán JA. Bone mineral density referral for dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry using quantitative ultrasound as a prescreening tool in postmenopausal women from the general population: a cost-effectiveness analisis. Calcif Tissue Int 2004; 74: 277-283. [ Links ]

19. Orozco P. ¿Es la osteoporosis un problema de salud prevalente en atención primaria?. Aten Primaria 2005; 35(7): 346-347. [ Links ]

20. Romera M, Carbonell C, Lafuente A. Osteoporosis: factores de riesgo y densitometría ósea. Med Clin (Barc) 2002; 118(8): 319. [ Links ]

21. Fuentes M, Ferrer J, Grifols M, Perulero N, Badía X. Manejo diagnóstico de las pacientes con osteoporosis atendidas en consultas de asistencia primaria. Semergen 2004; 30(supl.1):54. [ Links ]

22. Díaz M, Rapado A, Garcés MV. Desarrollo de un cuestionario de factores de riesgo de baja masa ósea. Reemo 2003; 12(1): 4-9. [ Links ]

23. Cummings SR, Nevitt MC, Browner WS, Stone K, Fox KM, Ensrud KE, et al. Risk factors for hip fracture in white women. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. N Engl J Med 1995; 332: 767-773. [ Links ]

24. Roy DK, O'Neill TW, Finn JD, Lunt M, Silman AJ, Felsenberg D, Armbrecht G, et al. Determinants of incident vertebral fracture in men and women: results from the European Prospective Osteoporosis Study (EPOS). Osteoporos Int 2003; 14: 19-26. [ Links ]

25. Reyes J, Moreno J. Prevalencia de osteopenia y osteoporosis en mujeres posmenopáusicas. Aten Primaria 2005; 35(7):342-7. [ Links ]

26. Marín F, López-Bastida J, Díez-Pérez A, Sacristán JA. Bone Mineral Density Referral for Dual-Energy X-Ray Absorptiometry using Quantitative Ultrasound as a pre-screening tool in postmenopausal women from the general population: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Calcif Tissue Int 2004; 74: 277-283. [ Links ]

27. Elliott ME, Meek PD, Kanous NL, Schill GR, Weinswig PA, Bohlman JP et al. Pharmacy-based bone mass measurement to assess osteoporosis risk. Ann Pharmacother 2002; 36:571-577. [ Links ]

28. Summers KM, Brock TP. Impact of pharmacist-led community bone mineral density screenings. Ann Pharmacother 2005; 39:243-8. [ Links ]

29. Goode JV, Swinger K, Bluml BM. Regional osteoporosis screening, referral, and monitoring program in community pharmacies: findings from project IMPACT: Osteoporosis. J Am Pharm Assoc 2004; 44(2): 152-160. [ Links ]

30. Ros I, Guañabens N, Codina C, Peris P, Roca M, Monegal A et al. Análisis preliminar de la adherencia al tratamiento de la osteoporosis. Comparación de distintos métodos de evaluación. Reemo 2002; 11(3): 92-96. [ Links ]

31. Tafur E, García E. Aproximación del rol de farmacéutico en la calidad de vida relacionada con la salud. 32. Lizán L, Badia X. La evaluación de la calidad de vida en la osteoporosis. Aten Primaria 2003; 31(2): 126-133. [ Links ]

texto en

texto en