INTRODUCTION

Pharmacists are highly trained healthcare professionals with responsibility for optimizing medication therapy and improving health and disease prevention.1 They are the experts in medication therapy with knowledge of identification, selection, pharmacologic action, preservation, analysis, standardization of drugs and medicines.2 Their specialized knowledge, experience and judgment enable them to improve the safety of medication use. Furthermore, they monitor medication therapy, patient's compliance, and therapeutic outcomes.3 Pharmacists can minimize the expenditures for pharmacological treatments and improve the cost effectiveness of medication therapy.

The value of pharmacists can vary depending on the settings of practice.4 Community pharmacists are the focal point of information and education to patients on general health issues.5 As already described by Calis et al., the pharmacists are not generally described as first aid providers, but patients make them the first sought health care professional when a problem occurs because of their easy accessibility and familiarity.6

Their essential role is to dispense safe and effective medications and provide free advice and health services. They constitute an integral part of a health network. They are highly accessible to patients. The community pharmacist has the most frequent contact with chronic disease patients of any healthcare professional.3 Therefore pharmacists can play a crucial role in counseling, disease prevention and management.4 They can reduce rates of medication inappropriate prescribing, maintain an electronic patient medication record, which tracks compliance, allergies, long term conditions and other patient safety matters. This can alleviate some of the costs associated with secondary care. It also builds patient's confidence in the healthcare delivery system.6

Pharmacists offer a front line focal point for unbiased information and education to patients and non-patients.6 With their knowledge and expertise, pharmacists can minimize the risk of treatment-induced adverse events and medications errors. When necessary, they will contact prescribers to clarify prescriptions, communicate errors and ensure their correction. The primary concern of all pharmacists is the health and welfare of their patients.5 Thus, healthcare providers should see the pharmacy as a key part of the primary healthcare team with frontline access to the public, and not just a retail business.

The concept of job satisfaction has been developed in many ways by many different researchers and practitioners. One of the most widely used definitions in organizational research is that of Locke, who defines job satisfaction as "a pleasurable or positive emotional state resulting from the appraisal of one's job or job experiences".7 Others have defined it as simply how content an individual is with his or her job; whether he or she likes the job or not.8 It is assessed at both the global level (whether or not the individual is satisfied with the job overall), or at the facet level (whether or not the individual is satisfied with different aspects of the job).8 Spector lists 14 common facets: appreciation, communication, coworkers, fringe benefits, job conditions, nature of the work, organization, personal growth, policies and procedures, promotion opportunities, recognition, security, and supervision.8

In Lebanon, all pharmacists must be registered in the Lebanese Order of Pharmacists (LOP) in order to practice. The latter is working to become a leading institution to improve the profession of pharmacy, excellence in patient care and scientific development in Lebanon and the Middle East. It seeks to raise the level of the profession, striving to apply the laws and to defend the rights of pharmacists and raise the level of the pharmacy practice and the development of scientific competencies. The LOP also provides favorable conditions to promote the arrival of the right drug to the patient and right use. Thus, pharmacists provide the best pharmaceutical service to the patient, work to protect the health and preserve his quality of life.6

Lebanon is a small country in the Middle East with a population of around four million inhabitants and 2897 community pharmacies with a ratio of 66.06 pharmacies per 100,000 inhabitants.9 Community pharmacies are licensed by the Ministry of Public Health. The latter regulates pharmacy practice, sets the price and the percentage of profits of all medicines under article 80. In 2014, the ministry changed the bracket of profit for drugs priced more than 200 USD from 18.5% to only 80 USD regardless of the original cost.10 The results of a study published in 2007 have shown that pharmacists working in Lebanon were dissatisfied due to physical straining, yet, the financial rewards outweighed the burden.11

In light of the recent decrease in drug prices, and the decrease in the financial rewards and pharmacy owners' net profit, the objective of this study is to evaluate the current community pharmacy owners' situation, based on their proper evaluation, financial rewarding and self-esteem concerning their role in the society.

METHODS

General study design

A cross-sectional study was carried out, using a proportionate random sample of Lebanese pharmacies from all districts of Lebanon (Beirut, Mount Lebanon, North, South and Bekaa). A list of pharmacies was provided by the LOP. A sample of 768 pharmacists was targeted to allow for adequate power for bivariable analysis to be carried out according to the Epi info sample size calculations with a population size of 4 million inhabitants in Lebanon, a 50% expected frequency and a 5% confidence limits.9 We decided to distribute 1600 questionnaires to take refusals into account.

Data collection process

The detailed questionnaire was distributed to pharmacies randomly by interviewers who were not related to the study. The latter explained the study objectives to each pharmacy owner; and after obtaining an oral consent, the pharmacist was handed the anonymous and self-administered questionnaire. On average, the questionnaire was completed by participants within approximately 10 minutes. The owner of the pharmacy had the choice to accept or refuse to fill the questionnaire. At the end of the process, the completed questionnaires were collected back by the inspectors and sent for data entry. During the data collection process, the anonymity of the pharmacists was guaranteed. The Lebanese University ethics committee waived the need for approval since the study was observational, anonymous and respected the individuals' confidentiality.

The anonymous questionnaire was in Arabic language, the native language in Lebanon, based on a thorough review of the related literature1-5; it was composed of different sections: socio-demographic characteristics, pharmacy employees and counseling-related questions, financial-related questions. Respondents were questioned about their current and previous working situations, comparing them between 10 years ago and nowadays concerning the average number of patients that enter the pharmacy daily, the average number of assistants and pharmacists present at the same shift in the pharmacy, average time given to the patient for counseling about a new or refill prescription. From another point of view, we asked the pharmacist to give us answers about our questions comparing the actual situation with the one 10 years ago concerning the following questions: monthly rent, total employees' salaries, municipality taxes, expanses (electricity, telephone, water, etc.), total amount of items destruction per year and total monthly sales and profit. Finally, using a 5-item Likert scale, we asked owners for their opinion if they think all patients need counseling, if they have enough time to counsel their patients, if they think counseling is important to them or not, if they can hire more pharmacists or buy a software for their pharmacy and if they think their situation was better a decade ago as compared to now. Dichotomous questions concerning their situation were asked: these would elicit rapid personal answers about work-related situation.

Statistical analysis

Data entry was performed by one inspector who was not involved in the data collection process. Descriptive statistics were calculated for all study variables. This includes the mean and standard deviation for continuous measures, counts and percentages for categorical variables. Paired t-tests were used to look for difference between the situation 10 years ago and nowadays. ANOVA was used to compare more than 2 means. The statistical package SPSS version 22 was used for all statistical analysis. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

RESULTS

Socio-demographic results

Out of 1618 distributed questionnaires, 1465 (90.5%) were collected back from pharmacy owners. The percentages of the results do not sum up to 100% since in our study, like all studies, not all the participants answered all questions.

Table 1 summarizes the socio-demographic and socioeconomic factors. The results showed that the mean age for the pharmacists was 42.52 (SD=11.47) years; 45.9% were males; 45.3% lived in Mount Lebanon, 17.1% in the South and 14.3% in Bekaa. The mean number of years for opening the pharmacy was 13.22 (SD=10.07) while the mean pharmacy surface was 67.53 (SD=40.38) squared-meters. The mean number of persons under the responsibility and direct care of the pharmacist was approximately 4 persons. The mean percentage of patients' low economic status was around 49.44% compared to 42.44% and 16.87% for medium and high economic status patients respectively, as reported by pharmacists.

Table 1 Sociodemographic characteristics of the pharmacists.

| Factor | value |

|---|---|

| Age in years [Mean (SD)] | 42.52 (11.47) |

| Years of opening the pharmacy [Mean (SD)] | 13.22 (10.07) |

| Pharmacy surface in squared-meters | 67.53 (40.38) |

| Gender [N (%)] | |

| Males | 672 (45.9%) |

| Females | 700 (47.8%) |

| District [N (%)] | |

| Beirut | 151 (10.3%) |

| Mount Lebanon | 664 (45.3%) |

| North | 183 (12.5%) |

| South | 251 (17.1%) |

| Bekaa | 210 (14.3%) |

| Persons under responsibility of the pharmacist [Mean (SD)] | 3.89 (2.93) |

| Percentage of low economic status patients [Mean (SD)] | 49.64 (24.53) |

| Percentage of medium economic status patients [Mean (SD)] | 42.44 (22.23) |

| Percentage of high economic status patients [Mean (SD)] | 16.87 (14.69) |

Economic status

Our study results showed that the number of hours that the owner spends in his pharmacy, the number of patients entering the pharmacy, the total number of pharmacists and assistants at the same time decreased significantly from 10 years until now (p<0.001 for all variables) (Figure 1).

The rent, as well as the total pharmacists' and employees' salaries, income taxes, municipality fees and the total bills (electricity, water, cleaning, security, etc.) per year significantly increased during the last 10 years (p<0.001). In addition, the yearly destruction of expired items significantly increased as well (p<0.001) (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Differences in pharmacists' financial situation between 10 years ago and now (Currency is U.S. Dollars). p<0.001 for all

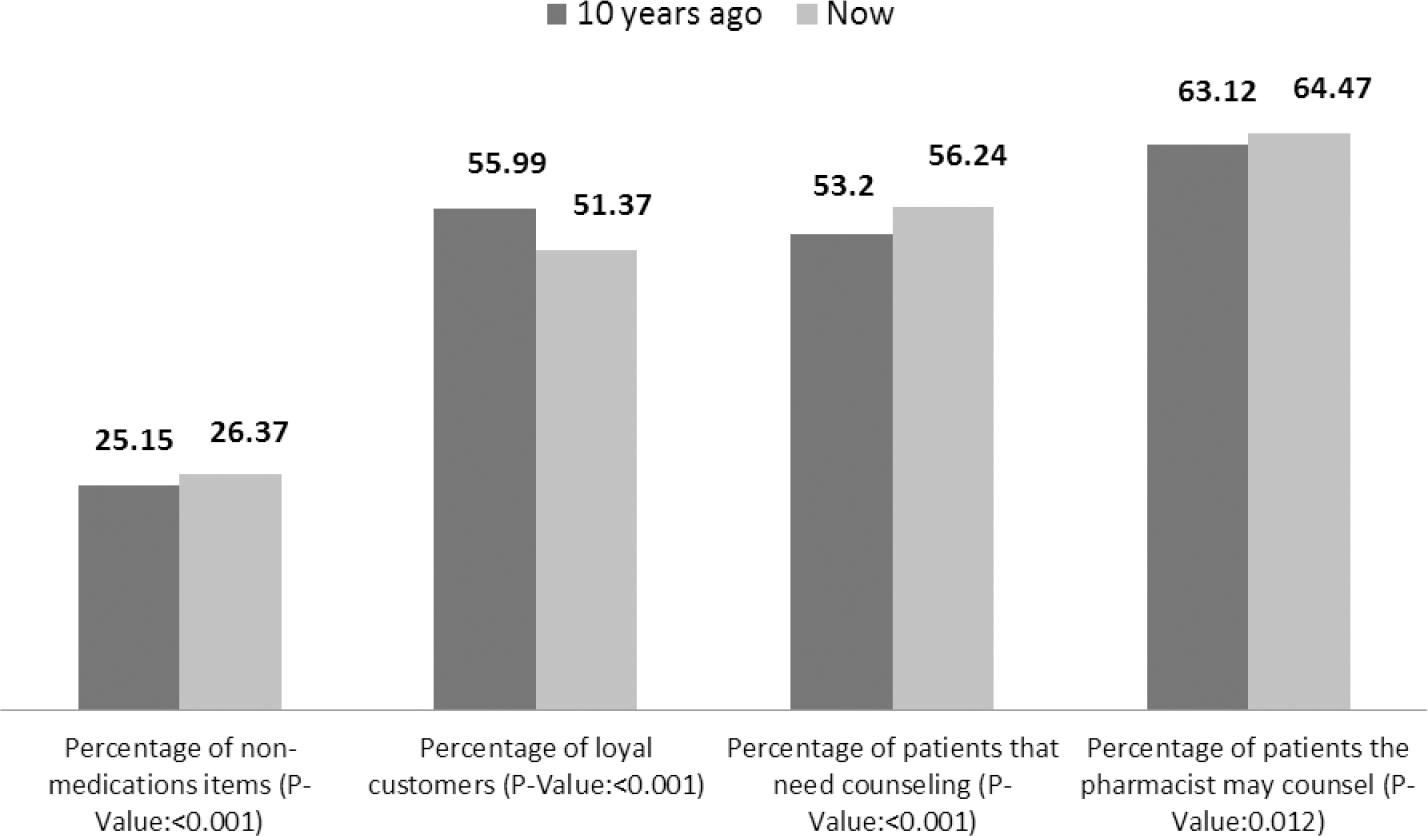

The percentage of non-medication items sales (para-pharmaceutical, baby, oral care products, etc.) increased significantly in community pharmacies (p<0.001) while the number of patients that needed counseling and the number of patients that the pharmacist may counsel significantly increased (p<0.001 and p=0.012 respectively). On the other hand, the number of loyal customers in the pharmacies decreased significantly (p<0.001) (Figure 3).

When comparing the total sales per month and the monthly profit between the last decade and these days, there was a significant difference between all 4 categories (p< 0.001). A post-hoc analysis showed that there was a significant difference between the categories themselves (p<0.001 for all categories) (Figure 4).

Patient counseling

On the other hand, when asked about their opinion in patient's counseling, 90% of patients agreed that patients need counseling while 92% agreed that there is enough time to counsel patients. Moreover, 95% of the owners said they cannot afford to hire any more pharmacists while 45% said they cannot afford buying software for their pharmacies. Finally, 89% of these owners admitted that their situation was better 10 years ago compared to nowadays.

DISCUSSION

This is a cross sectional pilot study carried out on community pharmacists in all Lebanon's districts to assess the socioeconomic status and the financial situation of these pharmacists nowadays as compared to the last decade.

Our results showed that the number of employees (pharmacists and assistants), the total number of monthly sales and profit, the number of loyal customers decreased significantly within 10 years while the total number of monthly bills, the yearly destruction and the number of patients that need counseling or that the pharmacist may counsel increased significantly within the same time frame.

Socioeconomic factors

The total number of employees significantly decreased throughout the years since the pharmacy owner is not making enough profit to hire more employees. The decrease in the price of medications without increasing the profit for the community pharmacist may play an important role in this issue. In addition, these pharmacists admitted that the total monthly sales and profit decreased as well probably because of the same reasons listed previously. Lebanon does not allow the free market to pharmacies. On the contrary, this market is regulated and must meet several requirements resulting laws and regulations from the LOP and the Ministry of Public Health. The decrease in the number of pharmacy by patients, increased overall spending in the last ten years and the reduction of prices by the Ministry of Health, made the financial statement for pharmacists even worse and resulted in even more serious losses, clearly shown by the results of this study. The yearly destruction of expired products increased probably because the agents and distributors are not taking the expired merchandise back and there is no one to hold them accountable for that, while the community pharmacist is paying the price.

Furthermore, the decrease in the number of patients in a pharmacy during the last ten years can be explained by the constantly increasing number of pharmacists and consequently the number of pharmacies in Lebanon. In fact, numbers from LOP showed that the difference between the increasing number of new graduates and the almost constant number of pharmacists who reach retirement age each year, is importantly increasing and highly disturbing. Despite the high rate of aging of the Lebanese population, the number of pharmacists is increasing every year, and a projection towards the following years is worrying, especially as the number of pharmacies per 100,000 inhabitants in Lebanon (66.06 pharmacies / 100,000) is ten times the global legal number.

Counseling

90% of patients agreed that patients need counseling while 92% agreed that there is no enough time to counsel patients. The acceptance by the majority of pharmacists to practice the clinical aspect of the pharmacy profession indicates that Lebanese community pharmacists are willing to get rid of the image of the "vendor" image that the profession suffers from since few years. The lack of time declared by pharmacists, and the inability to get appropriate help from assistant pharmacists and staff would explain the current situation of the profession.

Standards of pharmaceutical counseling require the pharmacist to be objective, reliable and up-to-date and include recommendations for the rational use of prescription as well as non-prescription medications.12 Since patient's counseling is very crucial and most of the community pharmacists are aware of that fact, these standards should be more applied. However, the lack of time due to the economic situation and the decrease in the number of employees in the pharmacies are examples of obstacles in front of good counseling to patients. Community pharmacists can be major players in rational therapy, and should remain competent to keep up with new developments. For this purpose, the OPL organizes continuing education conferences held all in Beirut, which creates a problem for pharmacists in regions outside the capital who find difficulties in transportation and time12; Thus the necessity of more decentralized lectures and seminars about up-to-date information for community pharmacists. Furthermore, studies have shown that pharmacies who apply integrated medication therapy management program, like the case of the United States, have improved patient outcomes.13,14,15,16,17

Similarly in Iraq, a study conducted in community pharmacies showed that patients seek medication knowledge, honesty and less business oriented as qualifications in a community pharmacist.17 Good, direct counseling would increase patients' satisfaction rate; this was demonstrated in a study conducted by Al Arifi in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.18

On the other hand, our results showed that the number of loyal patients decreased over the last decade. This is in opposite to the study done by Dossa et al. on Canadian patients that showed two major findings: individuals loyal to a single pharmacy were more likely to have better quality indicators of drug use and, for all indicators, the quality decreased with polypharmacies.19 These results are also expected since we do not have a medication therapy management program to follow up each patient's profile; the patient would seek a pharmacy that gives him a discount for cheaper medication instead of searching for good counseling. These results are further explained by the declaration of the vast majority of pharmacists that they do not have enough time to counsel patients.

Decrease in the number of employees and pharmacists' situation

Back in 2006, a study conducted by Salameh and Hamdan showed that freshly graduated pharmacists seemed more attracted by a community pharmacy position and medical representation; this is in opposite to our study's findings.11 In fact, the decrease in the number of assistants (pharmacists and staff) can have deleterious outcomes in the near future. In fact, because unmonitored drug therapy in Lebanon continues to pose a safety risk, patients are going to need more personal care11; for this reason, pharmacists worldwide are becoming personally responsible toward their patients20 and are educating them on the use of both prescription and over-the-counter medications.21 Unfortunately, if pharmacies remain overly busy and understaffed in Lebanon, a burdensome real-life workload can make these kinds of helpful conversations and information exchanges difficult to maintain.22 Moreover, frequent interruptions can increase required cognitive workload during counseling23 and can also result in dispensing and counseling errors.24,25 Similarly in Lebanon, these rates of discontent are alarming: studies have demonstrated that physically straining factors, such as work overload, understaffing, and inadequate schedules; we expect these factors to contribute to professional disappointment.26,27 Since this situation has consecutively proven to be related to higher rates of dispensing errors28, or burnout syndrome which jeopardize patients' health29, we recommend further studies to assess these outcomes.

In a study conducted by Abou Antoun and Salameh in 2009, community pharmacists were not thinking of changing their jobs.12 This was due to several factors, apart from the satisfaction of their current profession: the age of the pharmacist, stability in the pharmacy, the significant investments made in pharmacies, the refusal to work as a medical representative and the absence of other opportunities.12

Nowadays, the situation is the opposite: around two-third of these pharmacists admitted that their situation was much better 10 years ago. This is kind of expected since their profit decreased in the last decade while all their bills and daily life expanses increased in the same time frame, to the point that 43% of these pharmacists cannot afford buying a software program for their pharmacies. Clark found that overall job satisfaction included every variable used in the study, and found that income is correlated with overall job satisfaction.30 Based on the obvious uncomfortable financial situation of pharmacists in Lebanon, we suspect high job dissatisfaction, and we expect a high number of quits and labor market mobility in the near future. To curve this probable trend, a better grasp of job satisfaction determinants would allow for changes in public policy aimed at increasing job satisfaction: community pharmacies would thus be able to use job satisfaction to retain employees and create a better working environment.31 Further research is required to better assess this problem, while timely actions by concerned authorities are required to maintain the pharmacy profession.

Limitations

We are aware of the limitations that our study suffers from: A selection bias is possible because some areas were difficult to reach for community pharmacies especially in remote areas. Furthermore, it was not possible to compare the characteristics of responders and non-responders. An information bias is possible; although the owners used their computer system to estimate the total sales, profit and expenses, the numbers might not be accurate. Additionally, nonobjective understanding of questions is possible, as in all questionnaire-based surveys, particularly for situation issues: declared content reflects subjective perceptions of well-being and unhappiness might be a result of nonprofessional stressful factors, such as familial or environmental events.

CONCLUSIONS

Most Lebanese community pharmacists are not financially satisfied. The fact that the pharmacy owners cannot afford new staff members hiring can have deleterious effects on the patient. The ministry of Health along with the Order of Pharmacists in Lebanon should cooperate together to resolve this problem since they are two entities responsible for the patient's health. Further research is necessary for a thorough evaluation of Lebanese community pharmacists' professional fulfilment and its specific determinants, with the ultimate goal of finding adequate solutions for their needs.