INTRODUCTION

Medication errors are the major cause of morbidity and mortality in the medical profession. Several lines of evidence suggest that many inpatient medication errors occur at care transition points.1 Reconciliation of medication lists at care transition points (hospital admission, intra-hospital transfer, and discharge) is an important step in improving patient safety and preventing patient harm.2,3 Several international patient safety organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO)4, the Joint Commission International (JCI)5, and Institute for Health Care Improvement (IHI)6 acknowledged medication reconciliation as an important process to improve patient safety by identifying unintentional medication discrepancies at transitions of care points.

Acquiring a best possible medication history (BPMH) at hospital admission is an important step when a patient is admitted to the hospital. Because medication history upon hospital admission is generally used to determine the medication regimen during hospitalization, any discrepancy in this history may result in a discrepancy during hospitalization. In addition, this further ensures the safety of medication use since a medication reconciliation process prospectively identifies and prevents various types of medication errors and drug interactions. In the literature, the reported percentage of errors in medication reconciliation at hospital admission varies from 26.9% to 86.8%.7,8,9,10 Therefore, medication reconciliation on hospital admission, or at patient transition points is an important element to prevent and minimize the adverse drug events.

Aljadhey et al. in their national survey of medication safety practices in hospitals reported that only 18% of Saudia hospitals have defined policies and procedures regarding the implementation and education of medication reconciliation processes.11 Inaccurate medication reconciliation at admission to a hospital is common in Saudi Arabia. In one study, it was found that 37% patients had at least one discrepancy at admission.12 In a qualitative study conducted to identify perspectives of experts on medication safety in hospitals and community settings in Saudi Arabia, lack of implementation of medication reconciliation has been identified as one of the challenges for medication safety.13

Due to lack of human resources, hospitals are struggling in the implementation of a medication reconciliation process across all levels and intensities of care, and It may be adequate to target patients, who will most benefit from such medication reconciliation. There is a need to develop strategies that target a greater number of patients vulnerable to medication reconciliation error with the utilization of available resources in an efficient manner. This selection can be made based on various criteria such as availability of the services, involved patients or patients having certain characteristics that make them more susceptible to medication reconciliation error.

A pilot study was conducted to implement a reconciliation program in our center. The primary objective of this study was to describe the frequency and type of medication reconciliation errors due to unintended medication discrepancies identified by pharmacists performing medication reconciliation at admission in our hospital's medicine and surgical services. Each medication error was rated for its potential to cause patient harm during hospitalization. A secondary objective was to determine risk factors associated with medication reconciliation errors.

METHODS

Design and study population

This cross-sectional study was conducted in a 500-bed tertiary care teaching hospital in the eastern province of Saudi Arabia during the month of December 2015 with the aim to include as many patients as possible. Patients were selected from two medical departments (cardiology and endocrinology) and a surgical department. This choice was necessitated by the high admission rate in these two wards, and the need to include as many patients as possible in the study. The protocol was approved by the hospital's Ethical Committee and written informed consents were obtained from all the patients'.

Inclusion criteria: Inclusion criteria for patients were defined as a minimum twenty-four hours stay on the cooperating ward, and an existing drug therapy on admission.

Exclusion criteria: Patients discharged, transferred to another unit or hospital or deceased before the pharmacist could conduct admission medication reconciliation and patients who were not in a condition to give interviews were excluded from the study.

Data collection

Within 24-48 hours of patient admission, a clinical staff pharmacist or Pharm.D intern obtained a medication use history through comprehensive-structured interviews with the patient and/or caregiver before visiting the responsible physician. For this purpose, we used a standard form. For each drug the following information was collected: trade name, active ingredient(s), dose, frequency, route of administration, and duration of treatment as well as drug allergies. Over-the-counter medications and herbal drug use was also collected. Sources of information included: patient's medication bags, self-prepared medication lists and/or primary care reports. Medication lists from outpatient medical records were also reviewed through utilizing the electronic medical records (EMR) system. If the patient was previously hospitalized, available discharge summaries were also reviewed. Medication histories collected by the intern pharmacists were reviewed independently by three clinical pharmacists before entered into the main database.

The medication histories collected by pharmacists or pharmacy interns was regarded as the most accurate list available since it was based on all available information sources. The medication history obtained by the pharmacist was compared with hospital physician-obtained medication history and admission medication orders. Patients' progress records were also reviewed for intended discrepancies (e.g., modifications to pre-admission medications or formulary substitutions based on patient's current clinical status and desired treatment plan). The prescribing physician was then contacted regarding remaining unexplained discrepancies. Differences that were considered as discrepancies are shown in Table 1. A verbal intervention was made by a clinical pharmacist to the prescribing physician in all cases where reconciliation error was detected, in order to rectify that error.

Table 1 Types of medication discrepancies at the time of hospital admission

| Intended medication discrepancies |

|---|

| • Start of medication or modification of dosage justified by new clinical status of the patient • Medical decision not to prescribe a medicine or to change its dose, frequency or route of administration • Formulary/therapeutic substitution according to hospital policy |

| Unintended medication discrepancies |

| • Error of omission (untreated indication, failure to receive prescribed drug) • Modification of dose, frequency, and route of administration • Incorrect drug • Drug use without indication • Therapeutic duplication • Drug interaction |

All medication results reported are for prescription medications only. Over-the-counter medications and herbal drugs were excluded from the analysis. Similar to other published studies we classified aspirin as a "prescription medication" if taken for cardiovascular purposes.

Definition and classification of medication discrepancies, reconciliation error, and medication error

A medication discrepancy was defined as any difference between medications taken by a patient prior to admission and medications ordered upon admission to the hospital. Reconciliation discrepancies were divided into two main categories: intentional discrepancies and unintentional discrepancies. Differences that were considered as to be discrepancies are shown in Table 1. Any unexplained variances between what was recorded as prescribed in admission orders and what medications were taken by a patient were considered to be unintentional medication discrepancies and were recorded as a reconciliation error. An incorrect dosing frequency that did which does not change the total daily dose of a medication was not considered to be discrepancy. The omission of drugs with long dosing frequency e.g. once monthly, were also not considered to be discrepancies. Reconciliation errors that resulted in a change in medication order were considered to be medication error.

Potential Harm Assessment of medication errors

A multidisciplinary team (consisting of two senior consultants, two board certified pharmacotherapy specialists and a nursing superintendent) agreed upon the potential severity of medication errors using the widely recognized "National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (NCC MERP) index14, which assess and rates the potential harm to the patient. NCC MERP criteria were divided into three categories: 1) no error (NCC MERP category A); 2) error that did not reach the patient (NCC MERP category B); 3) no potential harm (NCC MERP category C); 4) monitoring or intervention potentially required to preclude harm (NCC MERP category D); 5) potential harm (NCC MERP categories E and above). Ratings of medication errors for their potential harms were rated by two study pharmacists, followed by blind, independent review by consultant physician. Inter-rater reliability of harm ratings for three categories of error groups was also analyzed. There was a substantial agreement rate between pharmacist and physician ratings (Cohen's kappa=0.78).

Study variables

The primary endpoint of the study was the presence of reconciliation error. Independent variables include sociodemographic and clinical factors (age, gender, chronic disease), administrative factors (a type of admission, professional category of the person who takes history), medication-related (an active ingredient, therapeutic group of medicine, polypharmacy) and reconciliation process related factors (source of information, duration of the interview, time required by the pharmacist to reconcile medication list).

For high-risk medications, discrepancies were assessed differently.15 High-risk medications were defined according to ISMP definition "drugs that bear a heightened risk of causing significant patient harm when used in error".16 Polypharmacy was defined as taking five, or five medications for more than three months. Comorbidity was defined as the presence of more than one chronic disease. The drugs were classified uniformly by using WHO Anatomic Therapeutic Classification (ATC).17

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis was performed on variables of interest. The mean and standard deviation are used for quantitative variables. Results of qualitative variables are present with frequencies and percentages. A 95% Confidence intervals were calculated for the proportions of patients with medication discrepancies. The quantitative variables comparison between the medical department and the surgical department was performed by student t-test. Categorical variables were compared by Chi-square test. Inter-rater reliability for assessing the potential for unintentional medication discrepancies (reconciliation errors) to cause patient harm was analyzed by kappa statistic for multiple raters. A multivariate logistic regression analysis, using a stepwise forward ‘LR' procedure and a selection threshold of P<0.10 was carried out to study the factors associated with the presence of reconciliation errors. Those variables with statistical significance in the univariate logistic regression analysis were included in multivariate logistic regression analysis. The results of the regression analyses are presented as unadjusted odds ratios (OR) with their 95% confidence intervals (CI); a probability value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test verified the calibration of the model. Discrimination ability of a fitted logistic model was assessed via the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. A significance level of 0.05 was used for all analysis and was performed using SPSS version 23.0.

RESULTS

Patient Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

Demographics and clinical characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 2. A total of 328 patients were enrolled in the study, 135 (41.2%) patients were admitted to the medical services department (cardiology and endocrinology), and 193 (58.8%) patients were admitted to the surgery department. Demographics and clinical characteristics of the study population were similar in both groups except a higher proportion of patients had a scheduled admission (93.3% vs. 29.6%; p<0.001) in the surgical services group and a significantly higher proportion of patients with co-morbidities were admitted to the medical services department group (40.0% versus 15.0%; p<0.001). Statistically significant differences were also found in the mean age of medical and surgical patients (63.9; SD=16.3 versus 58.4; SD=14.5; p<0.01). The average number of drugs per patient was higher in medical patients (5.5 versus 3.4; p <0.001). The time required by the pharmacist to reconcile a full list of home medication was 5.2 minutes/patient (SD=3.4 minutes; range: 2-19 minutes). About 32.6% of patients presented with a medication list or medication bag upon admission whereas 20.7% of patients' medication histories were retrieved through primary care reports.

Table 2 Characteristics of the study population

| Medical Services (n=135) | Surgical Services (n=193) | Total (n=328) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 55 | (40.8) | 64 | (33) | 119 | (36.3) |

| Male | 80 | (59.2) | 129 | (67) | 209 | (63.7) |

| Age groups | ||||||

| <65 years | 58 | (43) | 109 | (56.4) | 167 | (50.9) |

| ≥65 years | 77 | (57) | 84 | (43.6) | 161 | (49.1) |

| Type of admission** | ||||||

| Emergency | 95 | (70.4) | 13 | (6.7) | 146 | (44) |

| Scheduled | 40 | (29.6) | 181 | (93.3) | 182 | (56) |

| Comorbidities** | 54 | (40) | 29 | (25) | 83 | (25.3) |

| Polypharmacy* | 62 | (46) | 49 | (25.3) | 111 | (33.8) |

| Age* | 63.9 | (16.3) | 58.4 | (14.5) | 60.3 | (15.7) |

| Number of drugs* | 5.5 | (4.1) | 3.5 | (3.2) | 4.5 | (3.7) |

Statistically significant

**p <0.001,

*p <0.05

Reconciled medication and detected discrepancies

A total of 1419 drugs were recorded in the reconciliation process, 751 (53%) in medical and 668 (47%) in surgical services. About 1181 discrepancies were detected, of which 491 (41.6%) were considered reconciliation errors and affected 177 patients (54%), (Figure 1). The incidence of reconciliation errors in medical patients was 40.8% (273/668) and 29 % (218/751) in surgical patients (p<0.001). However, no statistically significant differences were found when the percentages of patients compared between medical and surgical patients with at least one reconciliation error (62.4% versus 56.8%, respectively; p = 0.591). Table 3 compares percentages of patients in the medical and surgical department with different types of intentional and unintentional medication discrepancies observed.

Figure 1 Distribution of frequencies of different types of discrepancies. M=Medical services, S=Surgical services

Table 3 Comparison of percentages of patients in medical department and surgical department with types of medication discrepancies observed.

| Medical | Surgical | Total % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | ||

| Justified or intentional discrepancies* | 69.8 | (62 -77.5) | 43.5 | (38.1 – 48.9) | 53.9 |

| Unjustified or Unintentional Discrepancies (Reconciliation errors) | 62.4 | (54.2 - 70.6) | 56.8 | (51.4 – 62.1) | 58.6 |

| Types of reconciliation errors | |||||

| Error of omission | 43.5 | (35.1 – 51.9) | 51.2 | (45.8 – 56.6) | 47.6 |

| Modification of dose, frequency and route of administration** | 19.4 | (12.7 – 26) | 8.2 | (5.23 – 11.1) | 12.7 |

| Drug use without indication | 2.3 | (-0.23 – 4.8) | 4.1 | (1.9 – 6.2) | 3.3 |

| Drug interaction/therapeutic duplication | 5.6 | (1.72 – 9.5) | - | - | 2.3 |

| Total | 81.4 | (74.8-87.9) | 68.1 | (63.1-73.1) | 73 |

Statistical significance level of

*p <0.05,

**p <0.001

Types of Reconciliation Errors

Drug omission was the most frequent reconciliation error in both groups (43.5% medical patients vs. 51.2% surgical patients, p=0.207), followed by the modification of dose, frequency, and route of administration (Table 3).

Distribution of frequencies of different types of intentional and unintentional discrepancies detected during admission medication reconciliation in medical and surgical patients are presented in Figure 1.

Medication classes and potential harm ratings

The most common therapeutic groups related to reconciliation errors were lipid-lowering drugs (12.4%), antihypertensives (9.3%), antidepressants (7.2%), and non-opioid analgesics (4.8%). Among high-alert medications, nineteen reconciliation errors were detected that required intervention, affecting about 8.6% of patients (95% CI 4.9 to 12.3) patients. Hypoglycemic agents (oral and insulin) and warfarin were the most prevalent high-alert medications with reconciliation errors (68.5% and 38.2%, respectively).

Table 4 provides distribution of percentages of reconciliations error in the medical and surgical patients in terms of a potential harm rating. Among 491 reconciliation errors, 48.7% were not likely to have been harmful to the patient (category A-C), 43.6% were likely to require monitoring or intervention to preclude harm (category D) and 17.7% were rated as may cause temporary harm and require some intervention or temporary harm with initial or prolonged hospitalization (category E-F).

Table 4 Potential harm ratings of medication errors due to reconciliation errors.

| Potential harm rating | No. (%) Interventions | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical (n = 218) | Surgical (n = 273) | Total (n = 491) | |

| NCC MERP Category A-C (No potential harm) | 63 (29.0) | 127(46.5) | 190 (38.7) |

| NCC MERP category D (required increased monitoring or intervention to preclude harm) | 94 (43.1) | 120 (44) | 214 (43.6) |

| NCC MERP category E-F** (Potential harm) | 61 (27.9) | 26(9.5) | 87 (17.7) |

**p <0.001

Logistic Regression Results for Risk Factors

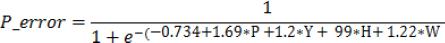

Table 5 presents multiple logistic regression results for the association of each risk factor with the likelihood of a patient having a reconciliation error. Advanced age (≥65 years old) (OR=2.7; 95%CI: 1.5 - 5.1, p<0.05); polypharmacy (OR=5.3; 95%CI: 2.4–11.6, p<0.05), hypoglycemic drugs (OR=2.6; 95%CI: 1.1–6.2, p<0.01) and use of warfarin (OR=3.4; 95%CI: 2.9–7.1, p<0.01) were risk factors independently associated with an increased risk for these errors. Although presenting a medication bag and/or medication list at the time of admission was also beneficial, it was not quite statistically significant (OR=0.73; 95%CI: 0.20–1.43). The final equation of regression model was:

Table 5 Factors associated with the errors in medication reconciliation

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio | 95%CI | Odds ratio | 95%CI | |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | Ref. | |||

| Male | 0.79 | (0.3 – 0.9) | - | - |

| Age groups | ||||

| <65 years | Ref. | |||

| ≥65 years* | 3.62 | (2.1 - 6.4) | 2.7 | 1.5 - 5.1* |

| Type of admission | ||||

| Emergency | Ref. | |||

| Scheduled | 0.83 | (0.5 – 1.4) | ||

| Day of admission | ||||

| Weekends | Ref. | |||

| Weekdays | 1.01 | (0.6 – 1.8) | - | - |

| Professional category | ||||

| Pharmacist | Ref. | |||

| Resident doctor | 0.42 | (0.1 – 1.2) | - | - |

| Nurse aid | 0.80 | (0.3 – 1.7) | - | - |

| Medication list or medication bag on admission | 0.73 | (0.2 – 1.4) | ||

| Polypharmacy* | 8.23 | (3.8 – 17.8) | 5.3 | (2.4–11.6) * |

| Comorbidities | 3.84 | (2.1 – 6.9) | - | - |

| Hypoglycemic drugs** | 2.71 | (1.2 – 5.8) | 2.6 | (1.1 – 6.2) * |

| Warfarin** | 3.06 | (0.7-12.2) | 3.4 | (2.9 – 7.1) |

*p <0.05,

**p <0.001

Where, P_error=Probability of reconciliation error; P=polypharmacy; H=hypoglycemic drugs; and W=warfarin treatment.

Hosmer-Lemeshow chi-square statistic was 0.245 with a significance of 0.89. The calculated AUCROC was 78.5% (95%CI: 75.3 to 82.0%), and the optimal cutoff point of medication reconciliation error was 0.53 with a sensitivity of 77.4%, a specificity of 69.5%, positive predictive value 82.3% and the negative predictive value of 63.7%.

DISCUSSION

Medication reconciliation at hospital admission has been shown to be an effective process to reduce unintentional medication discrepancies and medication errors in hospitalized patients.18 Due to a limited number of pharmacists on staff, other job responsibilities, and the time commitment, it may not be feasible for the individual hospitals to fully implement medication reconciliation for every patient across the continuum.19 However, evidence-based criteria for high-risk patients' medication reconciliation remains unclear. It is important to predict factors for medication discrepancies to develop effective strategies for the implementation of medication reconciliation. Therefore, this pilot study was conducted to identify those patients which are high-risk for medication reconciliation error in our institute so we can develop and implement screening criteria. Patients identified as high risk for unintentional discrepancies could then directed to a clinical pharmacist for a best possible medication history.

Among our study population of elderly patients, there was a high prevalence of admission medication reconciliation errors. We found that the prevalence of patients with at least one medication reconciliation error on admission was about 59% in both groups; similar findings have been reported in other national12 and international studies (range 21%–53.6%).9,20,21 However, there are also reports of low rates of error in medication histories at hospital admission (22). Previous studies that have assessed the admission medication reconciliation process are heterogeneous, with differences in methodology, patient population, definitions of medication discrepancies and reconciliation errors.1,7,22,23,24,25 Almanasreh et al. in their systematic review reported that a majority of studies related to medication reconciliation process used an empirical classification of discrepancies.26 In the same review, they suggested that "in order to understand the medication reconciliation process and identify the strategies for standardization, we need to clearly define and classify medication discrepancies as these are the only quantitative measures related to the medication reconciliation process".

The important finding of the present study is that almost half of reconciliation errors may have had a negative clinical impact on the patients if they had remained undetected, however, the actual number of potentially harmful errors were relatively small (n=87, 17.7%). Like our findings, previous studies have reported that omission of a drug is the most common type of medication error at the time of hospital admission7,9,21, followed by modification of dose, frequency, and route of administration. We have found that 47.6 % of hospitalized patients have at least one drug omitted from their regimen. Doctors are known to have difficulty gaining an accurate medication history on admission to the hospital.24,27,28

There are varying results from previous studies on predictors for errors in the medication history. We found that higher age (≥65years), an increased number of preadmission drugs and patients on hypoglycemic drug therapy and warfarin treatment were predictors of medication reconciliation errors. Likewise, some researchers have found that higher age22,23,29 and the polypharmacy at admission23,29 are significant predictors of reconciliation error in patients admitted to surgical (20) and internal medicine services.29,30 Evidence suggests that the use of drugs in elderly is often inadequate, partly due to the complexity of the prescription, health care-related factors and the patient's characteristics. Data in hospitalized patients suggest that this age group is more vulnerable to prescribing patterns of poor quality. However, our results might have differed if the patient cohort had been younger as the age groups of patients in our study wards were approximately equal (<65yrs=50.9%; >65yrs=49%). Although polypharmacy is considered as a risk factor for the occurrence of unintended discrepancies, some researchers have not found associations between the occurrence of unintended discrepancies and increased number of medications upon admission.22,30,31

High-alert medications (or drugs) medications may vary between institutions and health care settings depending on the types of medicines used and patients treated. JCI recommends shorter time frames for the reconciliation of high-alert medications.5 Among high-risk medications, we found unintended discrepancies in hypoglycemic drugs and warfarin, both subject to many different types of drug-drug and drug-disease interactions. In five instances, we found patients taking warfarin as a home medication, and upon hospital admission drugs ordered were found to interact with an interaction rating of "D" (recommendation to consider alternate). Boockvar et al. reported that chance of experiencing a discrepancy-related adverse drug event increases as the number of high-alert medications increase.32

The pharmacological classes of drugs most frequently involved in reconciliation errors vary according to studies but most pointing to the cardiovascular group as the most prevalent therapeutic group for medication history errors at admission to hospital. Tam et al.21 in their systematic review reported that therapeutic drug groups with more errors were cardiovascular drugs, sedatives, and painkillers. In our study, lipid-lowering drugs (12.4%), antihypertensives (9.3%), antidepressants, (7.2%) and non-opioid analgesics (4.8%) were most affected by reconciliation errors. Differences in prescribing patterns, patient selection, and formulary restrictions may explain the differences between various studies.

From the results of the present study, we can conclude that our model fits the data well with the good discriminatory power which can predict high-risk patients for medication reconciliation that allow us to prioritize our resource allocation and interventions. Nevertheless, leading authors suggested that there were few predictors associated with medication errors related to medication reconciliation at admission and well-designed processes for medication history verification were more important rather than patient characteristics.29

Study limitations: This study has important limitations. The generalizability of the study is questionable because it includes patients from two departments of internal medicine and surgical service admitted to a single hospital. Other groups may have different rates of reconciliation errors. Since medication histories were recorded by patient or caregivers' interviews, the number of medication errors may have been underestimated in patients who were too ill and had no caregiver. Although we used multiple sources to reconcile medication history, however, histories recorded by patients and/or caregivers' interviews may have been affected by recall bias. The classification of discrepancies into medication errors partly relies on subjective judgment by expert review of the medical record which is subject to bias and therefore we may have underestimated the number of medication errors.

CONCLUSIONS

From the findings of the present study, we can conclude that there is a high failure rate in medication reconciliation process in patients admitted to the medical and surgical department in our center. Based on our results, we found that patients over 65 years of age, patients with polypharmacy and regimens consisting of hypoglycemic agents and warfarin are more prone to medication reconciliation error. Staffing of clinical pharmacists can be valuable in performing structured medication reconciliations to prevent unintentional discrepancies at admission and reduce the risk of medication errors in these high-risk patients at our institute. Collaboration with nurses, physicians, and other health care providers on medication reconciliation is also vital.