Sexism ideology holds that men and women are not equal, which thus promotes and maintains different behaviors according to gender, gender inequality (O’Brien & Major, 2005; Sutton et al., 2008), and legitimizing violence against women (Garrido-Macías et al., 2020; Lila et al., 2013). This context includes sexual double standard (SDS), which refers to making an evaluation with different criteria of the same sexual behavior in men and women (Milhausen & Herold, 2002). Thus, by way of example, man-favorable SDS is taken as being normative insofar as men should enjoy more sexual freedom than women.

It is important to distinguish between adherence (i.e., support) to SDS and prevalence to SDSBy adherence we understand the intensity or strength with which someone is in favor of SDSIn operational terms, the degree of adherence will be the score obtained by someone on the scale evaluating SDSIn group terms (e.g., men or women), it will be group’s average score. Conversely, prevalence refers to the percentage of subjects who defend this norm, regardless of the intensity with which they support it.

Former studies have observed that men, compared to women, display more adherence to man-favorable SDS (Allison & Risman, 2013; Álvarez-Muelas et al., 2019; England & Bearak, 2014; Guo, 2019; Sierra et al., 2018) and that this attitude is found for men of practically all ages: adolescents (Monge et al., 2013; Moyano et al., 2017), young adults (Gutiérrez-Quintanilla et al., 2010; Sakaluk & Milhausen 2012), and older adults (Álvarez-Muelas et al., 2019; Sierra, Monge, et al., 2010), and the older they are, the more adherence they show (Álvarez-Muelas et al., 2019; Sierra et al., 2018). Nonetheless, except for the cross-cultural comparative study by Gutiérrez-Quintanilla et al. (2010) with university students, no studies have examined the prevalence of the SDS according to gender and age.

Adherence to such normative beliefs spells negative effects on sexual health (Álvarez-Muelas et al., 2020; Grose et al., 2014; Sánchez et al., 2005). Man-favorable SDS is related to favorable attitudes toward raping women (Jamshed & Kamal, 2019; Lee et al., 2010; Mittal et al., 2017; Moyano et al., 2017; Sierra, Costa et al., 2009; Wanfield, 2018), by constituting a predictor of such attitudes (Sierra, Santos-Iglesias, et al., 2010). It has also been associated with aggressive sexual behavior to women (Moyano et al., 2017; Russell & Oswald, 2001; Teitelman et al., 2013; Zurbriggen, 2000), by predicting male sexual coercion toward females (Sierra, Gutiérrez-Quintanilla, et al., 2009), female sexual victimization (Dunn et al., 2014; Koon-Magnin & Ruback, 2012; Lee et al., 2010; Sierra, Santos-Iglesias et al., 2010), and sexual violence recognition being more difficult (Kim et al., 2019). A recent meta-analysis by Endendijk et al. (2020) provides strong evidence for SDS relation of victims of sexual coercion. It also reports that SDS implies that women are evaluated worse than men who have been victims of sexual coercion which, in turn, results in women being more condemned and having a more damaged reputation (Endendijk et al., 2020).

As a result of the empowerment of women and their growing concern about, and awareness of, sexual violence, woman-favorable SDS has emerged (Kettrey, 2016; Milhausen & Herold, 2002), which is the opposite to man-favorable SDSIndeed woman-favorable SDS defends more sexual freedom for women than for men (Álvarez-Muelas et al., 2019; Papp et al., 2015; Sakaluk & Milhausen 2012; Sánchez-Fuentes et al., 2020; Thompson et al., 2018). To date, studies have not yet examined either the prevalence of this SDS typology or its relation with sexual health (e.g., with sexual aggression/victimization).

Changes in modern societies, with a more egalitarian and democratic gender ideology, can favor the appearance of new sexual scripts (Dworkin & O’Sullivan, 2005; Fasula et al., 2014; Seal & Ehrhardt, 2003; Suvivuo et al., 2010). Some authors have proposed that these new scripts represent a more conservative conception of sexual behaviors (Sakaluk et al., 2014), which could be expressed as better defending sexual shyness. It is feasible to assume that defending sexual shyness in heterosexual relationships does not apply equally for men and women. In line with this, and as Sierra et al. (2018) and Álvarez-Muelas et al. (2019) propose, evaluating SDS is necessary in both sexual freedom and sexual shyness areas. Sexual freedom is defined as the recognition and approval of benefit to men and women, of having sex freely while respecting sexual rights, whereas sexual shyness means the recognition and approval of men and women’s willingness to manifest decorum, chastity, and continence in sexual relationships. Likewise, normative pressure for gender equality that characterizes democratic western societies may favor an increasing prevalence of an egalitarian typology that defends the same sexual norm for both men and women. As far as we are aware, no studies describing the prevalence of this egalitarian SDS or its relation with sexual health can be found.

Therefore, it is necessary to determine the percentages of people supporting the three above-indicated typologies of adherence to SDS: man-favorable, woman-favorable, and egalitarian. A fourth can be added to these three typologies, which is characterized by ambivalence in displayed attitudes (Albarracin et al., 2005). The only self-report evaluation instrument that allows this distinction to be made in SDS typologies is the Sexual Double Standard Scale (SDSS; Muehlenhard & Quackenbush, 2011), which was recently adapted to the Spanish population by Sierra et al. (2018). The meta-analysis by Endendijk et al. (2020) recommends using this instrument to evaluate SDS, and suggests studying different SDS typologies from man-favorable SDS to woman-favorable SDS as a future research line.

As studies reporting the prevalence of different SDS adherence typologies are lacking in Spain, and by bearing in mind the importance of man-favorable SDS to explain sexual aggression/victimization behaviors, the aim of this work is to identify the prevalence, that is, percentages per gender and age of people who adhere to the four above-cited SDS typologies (man-favorable, woman-favorable, egalitarian, ambivalent) by considering two areas of SDS conduct: sexual freedom and sexual shyness.

Method

Participants

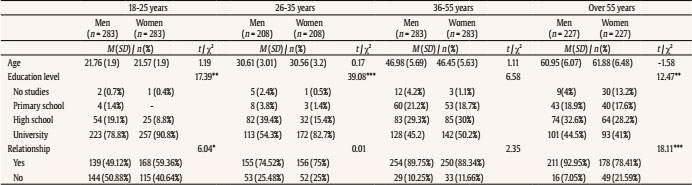

The sample was made up of 2,002 heterosexual adults of Spanish nationality, aged between 18 and 85 years, of whom 1,001 were men (M age = 39.62, SD = 15.69) and 1,001 were women (M age 39.61, SD = 16.02). The sample was distributed into four age groups following Arnett’s (2000) proposal according to subjective perceptions of adult status: 18-25 years (n = 566), 26-35 years (n = 416), 36-55 years (n = 566), and over 56 years (n = 454). Each age group was formed by 50% men and 50% women. Table 1 presents the sample’s socio-demographic characteristics divided into age groups and genders.

Instruments

Socio-demographic questionnaire. It includes questions about gender, age, nationality, sexual orientation, level of education, and partner relationship.

The Spanish version of the Sexual Double Standard Scale (SDSS; Muehlenhard & Quackenbush, 2011; Sierra et al., 2018). It consists in 16 items answered on a 4-point Likert-type scale from 0 (strongly disagree) to 3 (strongly agree), and two factors: acceptance of sexual freedom (ASF; the benefit of having sex freely while respecting sexual rights) and Acceptance of sexual shyness (ASS; the recognition and approval of the willingness to manifest decorum, chastity, and continence in sexual relationships). Each factor is formed by eight parallel items, that is, four pairs of items, of which half refer to sexual behavior attributed to men, and the other half to sexual behavior attributed to women. The scores of the eight ASF items allow the Index of Double Standard for Sexual Freedom (IDS-SF) to be obtained. The responses to the ASS items allow the Index of Double Standard for Sexual Shyness (IDS-SS) to be obtained. Both indices represent a bipolar measurement (between -12 and +12) to obtain four typologies of SDS adherence (man-favorable, woman-favorable, egalitarian, ambivalent) in sexual freedom and sexual shyness areas. The man-favorable typology includes those people with positive scores in the index (between +1 and +12). In the IDS-SF, this typology represents and defends greater sexual freedom for men than for women. In the IDS-SS it represents supporting less sexual shyness for men than for women. The woman-favorable typology is obtained from the scores that take a negative value (between -1 and -12). The IDS-SF represents defending more sexual freedom for women than for men, while the IDS-SS represents less defense of sexual shyness for women than for men. The egalitarian typology includes those people whose score equals zero in either the IDS-SF or IDS-SS and, in turn, who obtain a zero result in subtractions between pairs of parallel items that make up either of these two indices. This typology includes those people who defend the same criterion for men and women alike when evaluating behaviors referring to both sexual freedom (IDS-SF) and sexual shyness (IDS-SS). Finally, the ambivalent typology groups those people with a zero score in IDS-SF or IDS-SS, and who obtain non-zero results in some items that make up either of these two indices. This typology identifies those people who obtain inconsistent scores when evaluating the sexual behaviors referring to sexual freedom in the IDS-SF, and sexual shyness in the IDS-SSThe scale showed suitable internal consistency (ordinal alpha .84 for the ASF factor and .87 for the ASS factor), and its test-retest reliability coefficients were above .70 at 4 and 8 weeks (Sierra et al., 2018). It also proved to be invariant by gender and age (by eliminating the pair of items 11 and 14 which, in this case, showed DIF) (Álvarez-Muelas et al., 2019). So the present study chose to remove these items in ASFThe herein obtained ordinal alpha values were .82 and .88 for ASF, and .86 and .90 for ASS with men and women, respectively. In the different age groups, these values were .84 (18-25 years), .80 (26-35 years), .85 (36-55 years), and .84 (over 56 years) for ASF, and were .86 (18-25 years), .87 (26-35 years), .88 (36-55 years), and .89 (over 56 years) for ASS

Procedure

Data were collected via paper and pencil and on-line formats. As evidenced by previous studies (Arcos-Romero & Sierra, 2019; Carreno et al., 2020; Sierra et al., 2018), there were no differences in the answers obtained by both methods. The participants using the paper and pencil format answered in small groups or individually in classrooms, foundations, and community centers. Completed questionnaires were collected by a trained evaluator and placed in a sealed envelope. The online version was distributed through URL by social network, controlling IP address for each questionnaire and avoiding automatic responses by answering a security question consisting of a random arithmetic question. In both formats, participants accepted an informed consent form that described the purpose of the study and included an explanation of what their participation entailed. Anonymity and confidentiality were guaranteed. The study received prior approval from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Granada.

Data Analyses

For men and women in each age group (18-25, 26-35, 36-55, and over 56 years), prevalence was calculated with the percentages of adherence to the four SDS typologies (man-favorable, woman-favorable, egalitarian, ambivalent) on the two SDS dimensions (sexual freedom and sexual shyness). Differences for gender and age among the percentages of each typology were analyzed by chi-square tests. The differences within SDS typologies (man-favorable, woman-favorable, egalitarian, ambivalent) for gender and age, were calculated by comparison of column proportions, adjusting p values for Bonferroni correction. Finally, the intensity of the association between the variables was calculated using Cramer’s V.

Results

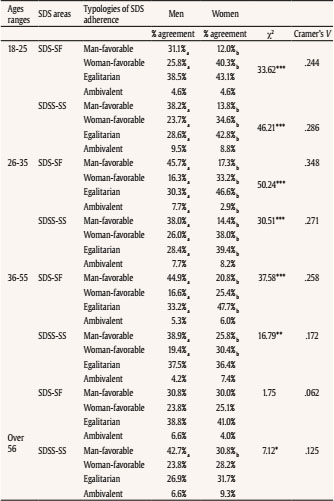

On the whole, the results for the SDS in the sexual freedom (SDS-SF) area indicated that 40% of the sample defined themselves as egalitarian, 28.8% as man-favorable, 26% as woman-favorable, and 5.2% as ambivalent. Regarding SDS in the sexual shyness area (SDS-SS), 34.2% defined themselves as egalitarian, 30.3% as man-favorable, 27.8% as woman-favorable, and 7.7% as ambivalent. Table 2 shows a gender comparison made of percentages of people in each typology in the two SDS domains and in all the age groups.

Table 2. Differences by Gender among the Percentages of the Adherence Typologies to the Sexual Double Standard-Sexual Freedom (SDS-SF) and the Sexual Double Standard-Sexual Shyness (SDS-SS) in Each Age Range

Note. Different subscript letters denote the proportions of groups that significantly differ

*p < .05,

**p < .01,

***p < .001.

In both man-favorable and woman-favorable typologies in the sexual freedom area, gender differences were found in the 18-25, 26-35, and 36-55 age groups, more men supported man-favorable SDS, and more women supported woman-favorable SDSFor the egalitarian typology, significant gender differences were observed in the 26-35 and 36-55 age groups, with more women than men in both cases. In the ambivalent typology, significant gender differences were found only for the 26-35 age group and with more men. In the sexual shyness area, significant gender differences appeared for the man-favorable typology in the 18-25, 26-35, 36-55, and over 56 years age groups with more men. In the woman-favorable typology, differences were recorded in the 18-25, 26-35, and 36-55 age groups with more women. In the egalitarian typology, differences were observed in the 18-25 and 26-35 age groups with more women. Finally, no gender differences were found in the ambivalent typology.

The comparison made of age groups with percentages of typologies of adhesion to SDS-SF and SDS-SS is found in Figure 1 for men and in Figure 2 for women. For men, significant differences appeared in the SDS-SF among age groups for man-favorable and woman-favorable typologies. A higher prevalence was seen in the former in the 26-35 and 36-55 age groups compared to the 18-25 and over 56 years age groups. In the woman-favorable typology, higher percentages went to the 18-25 age group than to the 36-55 age group. In the SDS-SS, no significant differences were found among age groups. For women in SDS-SF, significant differences appeared among age groups for man-favorable and woman-favorable typologies. The man-favorable typology presented a higher prevalence in the 36-55 age group than in the 18-25 age group, and for the over 56 years age group vs. the 26-35 age group. In the woman-favorable typology, higher percentages were obtained for the 18-25 years age group compared to the 36-55 and over 56 years age groups. In the sexual shyness area (SDS-SS), significant differences were observed for the man-favorable typology, with a higher incidence in the 36-55 and over 56 years age groups than in the 18-25 and 26-35 age groups.

The letter over each bar denote significant differences between groups, with higher scores for the group which is represented with letter over the bar.**p < .01.

Figure 1. Differences in Age Groups, in the Male Sample, among the Percentages of the Adherence Typologies to the Sexual Double Standard-Sexual Freedom (SDSSF) and the Sexual Double Standard-Sexual Shyness (SDS-SS).

The letter over each bar denote significant differences between groups, with higher scores for the group which is represented with letter over the bar.***p < .001.

Figure 2. Differences in Age Groups, in the Female Sample, among the Percentages of the Adherence Typologies to the Sexual Double Standard-Sexual Freedom (SDSSF) and the Sexual Double Standard-Sexual Shyness (SDS-SS).

Discussion

Interest has been shown in investigating adherence and changes in heterosexual sexual scripts (Masters et al., 2013; Morrison et al., 2015; Sakaluk et al., 2014). Part of this interest lies in the inconsistent results about the existence and scope of SDS (Bordini & Sperb, 2013; Crawford & Popp, 2003; Klein et al., 2019; Zaikman & Marks, 2017). With a large Spanish heterosexual population sample, this study describes the prevalence of adherence to four SDS typologies obtained with the responses of those surveyed using the Spanish version of the Sexual Double Standard Scale (SDSS; Muehlenhard & Quackenbush, 2011; Sierra et al., 2018). The four SDS adherence typologies correspond to man-favorable typology, woman-favorable typology, egalitarian typology, and ambivalent typology. As scales employed allow SDS adherence to be analyzed in sexual freedom and sexual shyness areas, prevalence of the four typologies appeared in both of these areas. Therefore, this study analyzed by gender and age groups differences in the prevalence of these typologies in relation to both sexual freedom and sexual shyness.

Generally speaking, the egalitarian typology obtained higher prevalence percentages in the sample on the whole. This typology obtained higher prevalence in the sexual freedom area, whereas man-favorable, woman-favorable, and ambivalent typologies showed higher prevalence in the sexual shyness area. These results should be interpreted within the research framework which has shown that preference for equity (i.e., egalitarianism) or for ingroup favoritism (i.e., man-favorable, woman-favorable) depends on many factors; e.g., beliefs, moral norms, salience of identity (Everett et al., 2015), or the positive (i.e., sexual freedom) or negative (i.e., sexual shyness) nature of resources to be shared between the in-group and the out-group (Gardham & Brown, 2001; Mummendey & Otten, 1998, 2001). From this viewpoint, it can be assumed that individuals in the sexual freedom area are more egalitarian because higher-order group identity (i.e., modern democrat) is emerging from the increasing support that Western societies grant both men and women to freely exercise their sexuality (Bianchi et al., 2000; García et al., 2012; Paul et al., 2000). However, when evaluating the distribution between men and women of negative resources (i.e., sexual shyness), endogroup favoritism is observed (i. e., man-favorable and woman-favorable typologies). This last result coincides with other previous ones (Mummendey & Otten, 2001), which could be due to the fact that, in this case, gender identity and motivations for favoring in-group are more present. Furthermore in modern societies, although clear norms exist as to the right to sexual freedom for both men and women, they are less stable and more ambiguous about sexual shyness. This ambiguity in norms about the importance of decorum and chastity might be a factor that facilitates the incidence of the ambivalent typology, which implies people’s inconsistent response.

Gender differences are found in the two areas of sexual behaviors, with a small effect size, except for the 26-35 age group in the sexual freedom area, which had a medium effect size. In-group favoritism prevailed with the male sample in both sexual freedom and sexual shyness areas, which means that the man-favorable typology grouped the biggest proportion of participants. This finding agrees with those of other researchers who have reported about adherence to the SDS (Allison & Risman, 2013; Álvarez-Muelas et al., 2019; England & Bearak, 2014; Guo, 2019; Sierra et al., 2018). The female sample showed higher percentages for egalitarian and woman-favorable typologies. On the one hand, these results imply that the norm in favor of equality for sexual behaviors is a proposal of social change with most support among women, but not among men. On the other hand, in light of our results, men who participated in this study opted mainly for an in-group favoritism attitude to defend their gender privileges in the society structure in Spain today. Nonetheless, although women first claimed gender equality, a marked prevalence for adhering to the woman-favorable typology appeared for the younger generation as a possible reaction to lack of sexual power (Milhausen & Herold, 2002), and in accordance with in-group favoritism (Greenwald et al., 2002; Rudman & Goodwin, 2004). This result falls in line with others obtained using samples of Spanish females (Álvarez-Muelas et al., 2019; Sánchez-Fuentes et al., 2020), which could be interpreted as the egalitarian ideology being linked with hierarchy-attenuating attitudes and behaviors (Ho & Kteily, 2020), but inequality could encourage in-group favoritism polarization (i.e., man-favorable and woman-favorable typologies).

Significant differences appeared among age groups. These differences followed a pattern in accordance with gender and the sexual behavior area (freedom vs. shyness). For men in the sexual freedom area, typology with the highest prevalence was man-favorable typology in the 26-35 and 36-55 age groups, whereas egalitarian typology predominated in the youngest age and over 56 years age groups. In other words, showing an attitude that favors a conventional gender role distribution was supported mainly by the male sector, and maintaining a stable heterosexual relationship was more likely for men. The sexual shyness area showed the same pattern and no significant differences appeared in all age groups made up of men. In fact, typologies that grouped a higher percentage of subjects appeared in this order, from more to less: man-favorable, egalitarian, woman-favorable, and ambivalent. Although the ambivalent sexism theory and its measurement have not centered directly on sexuality (Bareket et al., 2018), SDS is a sexism-related construct (Glick & Fiske, 1996). From this perspective, SDS favorable to men in the sexual freedom field would be related to hostile sexism, while SDS favorable to men in the modesty field would be related more to benevolent sexism that seeks to protect woman (Gómez-Berrocal et al., 2011; Noriega et al., 2020; Ramiro-Sánchez et al., 2018). The typology that most prevailed in the female sample, all age groups, and both sexual behavior areas (freedom and shyness) was egalitarian. Thus except for women in the over-56-years-age group, the second typology was woman-favorable given the numerical weight of its prevalence. This could reflect the pressure exerted on younger sectors of the female population to oppose man-favorable to favor women’s greater sexual freedom. Sexist attitudes are a risk factor and legitimize female violence in romantic relationships (Juarros-Basterretxea et al., 2019). Based on evidence demonstrating the predictive role of sexism and its different sexual violence (Durán & Rodríguez-Domínguez, 2019; Rollero & Tartaglia, 2018) and sexual health (Ford et al., 2017) forms, we propose conducting more future research to identify the possible predictor role about sexual health and sexual violence of SDS adherence types in sexual freedom and sexual shyness areas. To date, only the relation between man-favorable typology and sexual aggression/victimization has been studied. Based on the evidence of four adherence to SDS typologies (man-favorable, woman-favorable, egalitarian, ambivalent) in the Spanish population, and the increased number of breaches against sexual freedom during the 2015-2018 period (Ministerio del Interior de España, 2020), studying the relation of these typologies with sexual aggression/victimization is recommended to design more efficient programs for prevention and intervention of sexual violence.

In short, the distribution pattern of SDS adherence typologies varies in the Spanish population according to not only sexual freedom and sexual shyness areas, but also gender and age. Consequently, to be able to understand the role of the SDS in people’s sexual behaviors, and according to Endendijk et al. (2020), bearing in mind the different typologies that adherence to the SDS may adopt is recommended. Studying SDS in sexual shyness-related sexual behaviors is also stressed. This study proposes considering four adherence typologies of SDSTo do so, using the SDSS evaluation instrument (Muehlenhard & Quackenbush, 2011; Sierra et al., 2018) is proposed because it allows these SDS typologies to be determined in both sexual freedom and sexual shyness areas. Finally, we conclude that differences appear in the prevalence of SDS typologies through gender and age. These results suggest that to be able to understand differences in sexual behavior between men and women, it is important to first distinguish between adherence to SDS and prevalence of SDS adherence; second to consider the age group to which a person belongs; finally, to bear in mind the area (sexual freedom vs. sexual shyness) to which the conduct that the study object belongs. This study is not without its limitations: first, sample selection was made by non probabilistic sampling, which could affect the generalization of these results to the Spanish population. Furthermore, future research should analyze SDS in different sexual orientations. Second, the sample is homogeneous in ethnicity and cultural origin terms. According to the biosocial theory, culture is an important factor in the construction of gender roles and SDSTherefore, future studies should address both the differences between cultures and the role of gender roles to better understand the SDS phenomenon. Third, the SDS measure employed is an explicit measure that may ease socially favorable responses. In order to obtain attitude indicators that are capable of predicting behavior that favors gender sexual inequality, future research should minimize the social desirability associated with the SDS measure.