My SciELO

Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

FEM: Revista de la Fundación Educación Médica

On-line version ISSN 2014-9840Print version ISSN 2014-9832

FEM (Ed. impresa) vol.17 n.3 Barcelona Sep. 2014

https://dx.doi.org/10.4321/S2014-98322014000300001

The specialised training "Core Curriculum Drecree"

El "Real Decreto de Troncalidad" de la formación especializada

Arcadi Gual, Amando Martín-Zurro and Felipe Rodríguez de Castro

Fundación Educación Médica, FEM (A. Gual, A. Martín-Zurro, F. Rodríguez de Castro)

Sociedad Española de Educación Médica, SEDEM (A. Gual, F. Rodríguez de Castro)

After a lengthy process, the Ministry of the Presidency, at the request of the Ministry of Healthcare, Social Services and Equality, has finally enacted Royal Decree (RD) 639/2014, dated 25 July 2014 (BOE of 6th August 2014), which regulates different aspects of the specialised training of health care professionals (Table 1) and is colloquially known as the 'Core Curriculum Decree'.

Although all the aspects regulated by this RD are of interest in the training of specialists, this editorial will be referring to just one of them - the mandatory core curriculum (troncalidad). Everything started over a decade ago with the publication of the Spanish Ley de Ordenación de las Profesiones Sanitarias (Health Professions Regulation Act), which provided for the creation of a model of health care training based on a mandatory core curriculum. Six ministers of health later, the controversial RD has finally seen the light of day. Over a decade of debates, discussions, criticism, insults, hopes, disappointments, yearnings, claims in different forums and meetings had to be endured before it was eventually enacted. No matter which way you look at it, such a gestation is far too long. We therefore find ourselves before a complex regulatory framework that is sure to be the most significant change in specialised training since the system of medical resident interns (MIR) began in the late seventies. We are sure that, despite the discrepancies, if we know how to cooperate and we are capable of establishing suitable synergies amongst all those involved, it will be possible to develop the full potential contained within the RD and succeed in improving both the specialised training of health care professionals and the health care delivered to all citizens. Refusing to budge from maximalist standpoints or prolonging sterile debates will distance us from reaching both those goals.

Once the core curriculum has stopped being a project to become a tangible RD printed in black and white in the BOE (Spanish Official Gazette), the Fundación Educación Médica (FEM) considers it timely and fitting to reflect upon what is meant by mandatory core curriculum, who needs it in this day and age, and how it should be implemented in practice. Other questions, such as why a core curriculum has been so long coming or why so many groups (associations, societies and institutions) have had such strong feelings both in favour and against the core curriculum decree are perhaps not so relevant but nevertheless undoubtedly deserve some constructive thought.

Let us begin by establishing two premises:

- The mandatory core curriculum, just like any other reform, must be seen as an opportunity. The implementation of the 'MIR system' back in 1978 was undeniably such an opportunity and the mandatory curriculum must now also be another one, since it represents the first opportunity in 35 years to introduce across-the-board reforms into the model of training of specialists in the health sciences, which will in turn of course also affect the actual health care system itself.

- The RD is no finished article, but instead a framework in which a number of different aspects must be carried out. Hence, all the stakeholders involved in some way in this process (residents, tutors, health care staff, directors, professional associations, scientific societies, universities, health care administrations and politicians) are responsible, both individually and collectively, for ensuring that this development is well-balanced and heading in the right direction. Any prior assumptions, especially catastrophic ones, that, although devoid of any sound arguments, only forecast disaster are unacceptable.

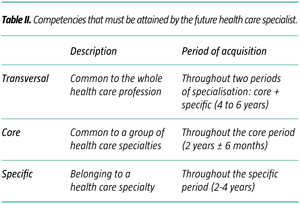

What then is the mandatory core curriculum and why is it necessary? The mandatory core curriculum is a way of organising specialised training so that specialties that share common competencies - regard-less of their number - are grouped in blocks of core subjects. Thus, two periods can be distinguished in specialised training: one in which students develop those competencies that are common across several specialties, that is to say, those that make up the core block (or tronco), and one in which the competencies of the specialty itself are acquired. In this organisational system of core subjects there are three clearly defined types of competencies that the future health care specialist must accomplish (Table II): transversal (common to a health care profession), core (common to a set of specialties, to a core block) and specific (belonging specifically to one health care specialty).

Without a doubt the competencies a specialist has to acquire must be well established by those responsible for the specialty both nationally and internationally (National Commission and Scientific Societies). Likewise, the competencies to be attained by a specialist must of course be the same, regardless of whether they are accomplished by means of linear or core training. If we take a look at the training in a single isolated specialty, cardiology, for example, there should be no difference between cardiologists trained with the present linear process and those whose training is based on the new core curriculum. Both cardiologists must display the same array and level of competencies, and they must have acquired them over a similar period of time. Yet, if we examine the training processes of all the specialists in a global manner, training based on grouping specialties into different core blocks exhibits greater plasticity, allows the learning of common competencies within a certain group of medical residents to be addressed better, makes it possible to optimise resources and teaching strategies, and also simplifies the processes involved in retraining in another specialty for professionals who wish to do so.

For years we have insisted on the fact that the main drawback of the current system of medical resident interns is its rigidity, which makes it more difficult to switch over from one specialty to another, and penalises the optimisation of resources and strategies. The core curriculum system addresses this criticism and, to a large extent, resolves it. What is wrong with the process of training specialists by means of the core curriculum system? Its weakest point is surely its complexity. Its implementation is clearly more complicated than that of the linear process, especially when the latter has been under way for over three decades, which has allowed its initial difficulties to be forgotten. But is organisational complexity a good reason to paralyse the reform of specialised training? It is only natural for a change of such dimensions to generate concern, but naturally it is not reason enough to hold up progress.

In short, the mandatory core curriculum is no more than an organisational model of specialised training that, with respect to the current process, should allow for greater clarification and concretion in the different types of competencies to be acquired by professionals, on the one hand, and make it possible to achieve greater organisational plasticity of both educational and learning processes, on the other.

The second question we have posed concerns how the implementation or change from a linear model to a core model should be carried out. The answer cannot be simpler: gradually, with the active participation of all the stakeholders and by drawing on feedback gleaned from the actual evolution of the process itself. It is not our aim here to perform a detailed analysis of the aspects that will have to be taken into account in implementing the RD. The FEM and the Spanish Society for Medical Education (SEDEM) have begun an analysis, from an academic point of view, in order to define their standpoint vis-à-vis the RD and even sketch out strategies for its implementation. In this editorial we can only hint at the general guidelines that, in our opinion, should direct the different processes.

The (central and autonomic) administrations involved are the ones that take on the greatest and ultimate responsibility for the success of the process of progressively implementing the mandatory core curriculum, in accordance with the deadlines set out in the actual RD that regulates it. Nevertheless, our own experience and that of other countries shows that it is advisable to ensure that the main participants in carrying out this process are the leading academic and professional institutions and organisations with an interest and proven experience in this field.

One of the keys to the success of the process of implementing the core curriculum model in the training of specialists must lie in the flexibility of the legal and technical instruments it is endowed with in order to be able to keep adapting itself, on a regular basis, as new contexts come into being. The decisions that must be taken throughout the process have to be based on reliable data obtained using methods that are scientifically sound and designed with criteria that are homogenous across the state as a whole in order to ensure the balanced development that is required.

Evaluating the rate at which the process is taking place has to be based on the application of both quantitative and qualitative methodologies to allow reliable estimations of its different facets to be obtained. The first of these two methodologies must generate data, for example, about compliance with the schedules foreseen for setting up commissions and groups, about the design and development of the programmes of core and specific training, about the requirements for accrediting new teaching units, and about their composition, norms of operation and the equivalences of the processes of assessing core and specialty materials and areas of specific instruction. On the other hand, those of a qualitative nature must be designed in such a way as to offer instruments that allow continuous periodic monitoring of the general and local problems encountered by the process of implementation, and also the opinions and proposals of the different stakeholders collected through surveys or interviews, for example.

We must be aware of the need to anticipate the different problems that will be generated by the process of implementing the core curriculum model. The success of the change of model will largely depend on the extent to which both structural and organisational problems are anticipated. Moreover, before starting the process, it would also be necessary to define the resources required by the change of model and to foresee the unnecessary ones present in the current model. Table III shows some of the aspects that must be taken into account before putting the new core curriculum system into practice. At this point it is worth stressing that cooperation and trust among the different parties will play a key role in the success of the process of developing and implementing the core model.

We do not want to finish without one last reflection on the reasons why this RD has taken so long to enact when apparently there was unanimous agreement regarding the rigidity of the system of specialised training and calls were being made, also unanimously, for a solution involving a change of structure in which specialties were grouped according to the similarities among them. Indeed, the long period of gestation the different health care administrations forced the newborn RD 639/2014 to undergo is directly related to the belligerence (in favour, but above all against) that the change of model has caused within different collectives, associations, societies and institutions. As we understand it, this hostility has been disproportionate, firstly because it has lacked an overall perspective and secondly because it was based on giving priority to the interests of certain specific groups rather than those of more general ones. The absence of any solid reasoning and the presence of arguments fraught with presuppositions have been frequent in the above-mentioned theses. Furthermore, arguments against the reform have also been invoked, although in fact they were suggesting the need for a new structure.

In short, we believe that the reformation of specialised training, although complex and not devoid of its organisational difficulties, was advisable and represents an opportunity to improve. For this to occur, and for specialised training to reach excellence, the different collectives will have to work jointly and trustingly, and establish synergies and mechanisms of supervision and feedback in order to retune the processes that are proving to be difficult to fit in. The future does not lie in the BOE, but instead in the stakeholders' will. If we are not interested in succeeding, doing nothing will suffice, but if what we want is the best specialised training, then we must get on with it. Anyone going to refuse?

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Fundación Educación Médica

Departamento de Ciencias Fisiológicas I

Facultad de Medicina

Universitat de Barcelona

Casanova, 143

E-08036 Barcelona

E-mail: agual@fundacioneducacionmedica.cat

text in

text in