1. INTRODUCTION

Quality of life is a multidimensional concept with various interpretations over time; initially, it was limited to basic needs, and later it has been extended to health aspects. The World Health Organization has defined it as the individual's perception of their position in life within the cultural context and value system in which they live; and regarding their goals, expectations, norms, and concerns [1, 2]. There is interest in assessing the perception of sick and healthy populations' physical, mental, and social well-being, especially pregnant women [3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8].

The anatomical, physiological, and biochemical changes accompanying pregnancy, emotional maturation, and women's interaction with their environment contribute to the perception of well-being and quality of life [3, 4, 7, 8, 9, 10]. Quality of life assessment in pregnant women has preventive reasons since physical, psychological, and environmental health deterioration has negative obstetric and perinatal impacts such as preterm delivery and low birth weight [5]. In addition, Da Costa et al. [11] warn that pregnant women may have a significantly worse quality of life than the general population.

Several instruments are available to assess different spheres of health and measure the quality of life: World Health Organization Quality of Life BREF (WHOQOL-BREF), World Health Organization Quality of Life Questionnaire (WHOQOL-100), Short Form 36 Health Survey Questionnaire (SF-36), Short Form 12 Health Survey Questionnaire (SF-12), Nottingham Health Profile (NHP), Sickness Impact Profile (SIP) [2].

Assessing pregnant women's quality of life is an essential public health measure in reproductive health and prenatal care [7]. However, there are insufficient studies on Latin American pregnant women. The objective was to establish the frequency of deterioration of physical, psychological, social, and environmental quality of life and identify associated factors in pregnant women residing in cities of the Colombian Caribbean who attended an outpatient prenatal consultation.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

A cross-sectional study, part of the research project "Biopsychosocial health in low-risk pregnant women in prenatal consultation or hospital management". Pregnant women who had seven or more weeks of gestation (confirmed clinically and sonographically) and who attended outpatient prenatal care between the last quarter of 2019 and the first of 2021 were included. Patients were invited to fill out a form when they left the consultation with the obstetrician, who considered them fit to continue their daily lives. Previously trained nurses informed them of the anonymous and voluntary nature of the study, about the objectives, and collected the informed consent or assent signature if they were minors. Pregnant women lived in urban or rural populations from Bolívar, a department in the Colombian Caribbean region. Those who left the consultation and were referred to the emergency room or hospitalization units were not considered. Women who did not want to participate and those who reported limited literacy or did not understand the form questions were also excluded.

The form had two parts; the first had questions about sociodemographic characteristics and clinical history data. The second was the Spanish version of the World Health Organization Quality of Life BREF (WHOQOL-BREF) scale. This instrument allows for assessing perceived quality of life through 26 easy-to-interpret short questions. The first two questions ask the opinion about the quality of life and general health. The remaining questions are grouped into four domains that are assessed separately: physical health (items 3, 4, 10, 15, 16, 17, 18), psychological health (5, 6, 7, 11, 19, 26), social relationship (items 20, 21, 22), and environmental relationship (items 8, 9, 12, 13, 14, 23, 24, 25). Each item has Likert-type response options, from one to five points, according to their opinion and perception of the last month. The higher the score, the better quality of life. The facets incorporated within domains: physical health (activities of daily living, dependence on medicinal substances and medical aids, energy and fatigue, mobility, pain and discomfort, sleep and rest y work capacity); psychological health (bodily image and appearance, negative feeling, positive feeling, self-esteem, spirituality/religion/personal beliefs, thinking, learning, memory and concentrations); social relationships (personal relationships, social support, sexual activity); environmental (financial resource, freedom, physical safety and security, health and social care; accessibly and quality, home environment, opportunities for acquiring new information and skills, participation in and opportunities for recreation/leisure activities); physical environment (pollution/noise/traffic/climate, transport) [2]. For the present study, deterioration of each domain was considered when the score was below the average of the studied pregnant women. Validations of this scale in Spanish-speaking pregnant women were not found. The version applied in a healthy Colombian population of both sexes was used. They obtained Cronbach's Alpha of 0.85, 0.86, 0.84, and 0.83 for the physical health, psychological health, social, and environmental relationship domains, respectively [12].

The forms were applied daily until completion and reviewed weekly. Those filled out correctly were stored in the "accepted" folder and the incomplete ones in the "discarded" folder. When the application was completed, the accepted forms were entered into a Microsoft Excel© database.

The sample size calculation was performed using data from the vital statistics [EEVV] corresponding to the year 2018, reported by the National Administrative Department of Statistics (DANE) of Colombia, which estimated that the number of births in that year for the department of Bolivar was between the range of 28,841 to 49,160. https://www.dane.gov.co/files/investigaciones/poblacion/cifras-definitivas-2018.pdf. Births were used because information about the number of gestations was not identified. The upper range was considered, and a sample size of 382 participants was calculated with the EPIDAT 3.1 software (Epidemiological analysis from tabulated data), with a confidence level of 99%, an expected proportion of 50%, a significance of 1%, and absolute precision of 5%. One hundred fifty-two women (40%) were added to compensate for discarded documents; therefore, there were 534 forms available.

The statistical analysis was performed with Epi Info-7. Continuous variables are expressed as means and standard deviation, and categorical variables as absolute values, percentages, and 95%CI. Four adjusted logistic regression models were performed to estimate the association between the four domains of quality of life (dependent variable) with the sociodemographic and clinical aspects included in the study (independent variables). Associations are presented with OR [95%CI]. A value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The research project was conducted with the ethics committee of the Santa Cruz de Bocagrande Clinic, Cartagena approval, act 04-2018 of 5 February 2018. In turn, the project has the endorsement of the research vice-rector of the University of Cartagena, Colombia. The Declaration of Helsinki principles and the scientific, technical, and administrative standards for health research established in the Belmont Report and the Colombian Ministry of Health 8430 Resolution of 1993 were considered.

The ethics committee of the Santa Cruz de Bocagrande Clinic, Cartagena, Colombia, according to act 04-2018 of 5 February 2018, approved the study.

3. RESULTS

Of the 534 forms applied, 25 (4.6%) were incomplete, incorrectly filled out, or with erasures and, for this reason, were eliminated. The study was carried out on 509 pregnant women, 33.2% above the sample size.

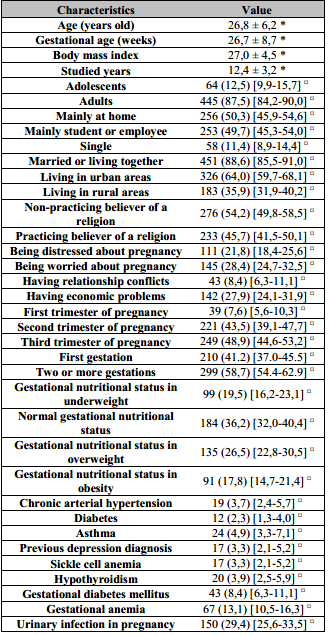

The mean age of the participants was 26.8±6.2 years, the minimum age was 13, and the maximum was 42; 12.5% of all were adolescents. Half of the respondents were housewives, 41.2% were first-time pregnant women, 64.0% lived in urban areas, 11.3% were single, and 8.4% had relationship problems. The mean gestational age was 26.7±8.7 weeks, and 48.9% were in the third trimester of pregnancy (Table 1).

Table 1: Sociodemographics characteristics of sample (n=509).

Values expressed as: *:mean ± SD;

¤:n (%) [IC95].

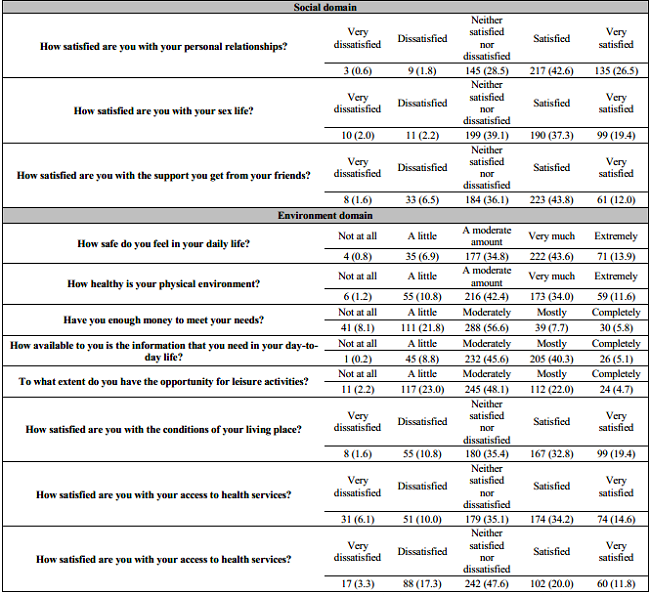

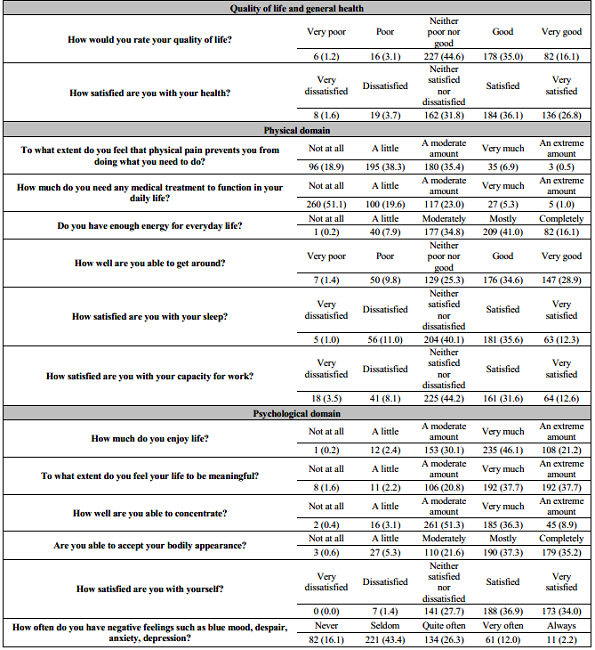

Of all, 4.2% of the pregnant women rated their quality of life as very poor or not very normal and 5.2% considered themselves dissatisfied or very dissatisfied with their health. Some of the answers to the WHOQOL-BREF items were: 40.5% stated that they had experienced sadness, anxiety or depression in a quite often, very often or always at some point during the pregnancy. They also stated that they were little or not at all satisfied: 12.0% with their sleep, 11.6% with their ability to work, 16.1% with access to health services and 8.1% with the support of his friends. On the other hand, 29.9% had little or no money to cover their needs. The Table 2 presents the opinions given to the items that are part of the quality of life and general health, as well as those that explore the physical and psychological domain. The responses to the items that are grouped into the other two domains, social and environmental, are shown in Table 3.

Table 2: WHOQOL-BREF scale. Quality mof life and general health, Physical domain and Psychological domain (n=509, %).

The scores obtained for the physical health, psychological health, social relationship, and environmental relationship domains were: 14.65±2.20, 15.38±2.37, 14.94±2.67, and 13.26±2.53, respectively. Of the total number of pregnant women: 250 (49.1%) presented deterioration of physical health or psychological health, 281 (55.2%) had deterioration of social relationships, and 270 (53.0%) had deterioration of environmental relationships. Cronbach's alpha was 0.70; 0.78; 0.70, and 0.85 for the domains of physical health, psychological health, and social and environmental relationships.

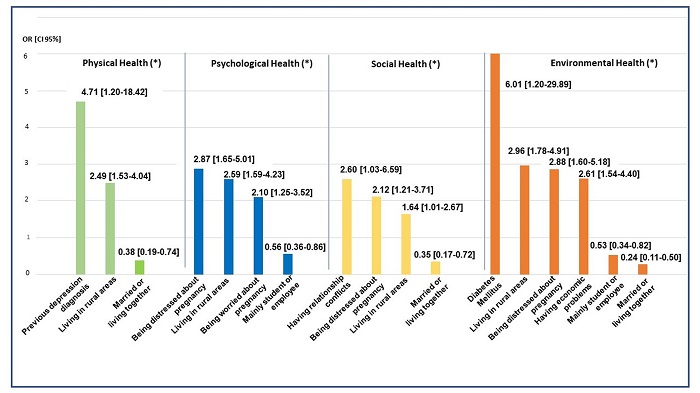

A significant association was found with impairment in at least one of the domains explored for the following situations: having a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus or depression, being distressed or worried about pregnancy, and having marital conflicts or economic problems. Living in rural areas, compared to urban areas, was associated with twice as much impairment in all domains. Being married or living together, compared to being alone, was associated with 62% less possibility of deterioration of physical health, 65% less deterioration of social relationships, and 76% less deterioration of environmental relationships. Being a student/employed versus being a housewife was associated with 44% less possibility of psychological health deterioration and 47% less environmental relationships deterioration (Figure 1). Being adolescents compared to adults, and having first pregnancy concerning having two or more, were not associated with deterioration in any of the domains (p>0.05).

4. DISCUSSION

Half of the evaluated pregnant women had physical health, psychological health, social relationships, or environmental relationships deterioration, in contrast to Dağlar et al. [13], who identified less deterioration in physical health: 13.1%, psychological health: 15.9%, social relationships: 10.4%, and environmental: 17.4%, using WHOQOL-BREF in Turkish pregnant women. The average score of the domains in our study was similar to the one identified in Brazilian women [14] and better than the one found in Polish pregnant women [9]. Cultural reasons, social, family, economic and educational influences, perceptions about the female role and motherhood, life experiences, and others can explain these differences [13].

We found that a previous depression diagnosis was associated with four times the odds of physical health impairment. Gariepy et al. [15] observed that a history of depression or anxiety in US pregnant women was associated with low scores on the physical domain of quality of life. Likewise, Mourady et al. [16], with WHOQOL-BREF, found that depression in pregnancy was associated with impairment in all four domains. Depression in pregnant women and quality of life have an inverse relationship; the worsening of depressive illness contributes to the loss of general, physical, and psychological health by affecting neuroendocrine pathways and altering the immune system [17, 18].

Being distressed or worried about pregnancy was associated with deterioration in psychological health, social relationships, and environmental relationships in the evaluated pregnant women. A study using WHOQOL-BREF in Iranian pregnant women observed a negative relationship between feeling worried about pregnancy and psychological health [18]. Lebanese pregnant women also reported that the more they worried about pregnancy, the more significant the decrease in quality of life with physical, psychological, and environmental deterioration (p<0.05) [16]. Several authors [16, 18, 19] pointed out that mental pressures and worries during pregnancy affect organic functioning and negatively impact health.

Couple of conflicts were associated with a greater possibility of deterioration in social relationships. In the same direction, Calou et al. [3], in Brazilian pregnant women, identified that a stable couple relationship was associated with better quality of life. We noted that being married/cohabiting with a partner, compared to being single, was associated with less deterioration in social and environmental relationships and physical health. Similar finding is reported by several authors, who point out that emotional support from the partner strengthens the affective connection and improves self-esteem, which is reflected in a better quality of life [13]. Economic problems affected the environmental relationship of the studied pregnant women, like the finding in Turkish pregnant women, who perceived that their income exceeded their expenses. They had better environmental relationships and psychological and social health [13]. Low socioeconomic status leads to late prenatal care, dissatisfaction with life, and affects mental health [20]. On the other hand, performing work activities, being independent, or having financial stability are associated with good self-esteem and self-sufficiency, which contribute to an adequate quality of life [3, 7, 13]. Among the pregnant women evaluated, having an occupation outside the home or being a student, compared to being a housewife, was associated with less deterioration in environmental relations and psychological health.

The only condition we found in the present study associated with impairment in all four domains was living in a rural area. The same finding was noted in pregnant women living in Pakistan [21]. Similar are the observations of Arute et al. [22]. They found in pregnant women in Nigeria that residents in rural areas, compared to urban areas, had deterioration that is more significant in the domains, except social relationships using WHOQOL-BREF. Urban pregnant women may have greater access to health services, transportation, education, and job opportunities and have fewer unmet needs, all of which are associated with a better quality of life [21, 22].

We found that having diabetes mellitus was associated with a greater possibility of environmental deterioration. Pregnant women affected by diabetes mellitus, especially when they lack sufficient education about the disease, often have a poor perception of their health, anxiety, and high worries, which deteriorates their quality of life [23]. We did not observe an association with maternal or gestational age or parity. Nor with other chronic or gestational pathologies, including gestational diabetes. However, Iwanowicz-Palaus et al. [9], in a case-control study using WHOQOL-BREF, reported that those affected by gestational diabetes had deterioration that is more significant in the four domains.

The strength of this study is to make visible in a population of Latin American pregnant women undergoing prenatal care, considered healthy by their obstetricians, the magnitude of the deterioration of their physical, psychological, social, and environmental health. It provides a group of biopsychosocial factors related to health deterioration, including situations that are not usually addressed in prenatal care. It is crucial to explore pregnant women beyond the purely medical or obstetric aspects and to require that health professionals with expertise in mental health or social issues join the team that cares for pregnant women. Finally, this is one of the few studies that has applied a scale proposed by the World Health Organization, widely used worldwide, to the Latin American population. It has limitations inherent to cross-sectional designs; it determines statistical associations, not causes. The results may be specific to the group studied, and extrapolations should be avoided. It is a limitation not to have asked about nausea or vomiting during pregnancy, which is associated with worse physical health [3, 13, 24], and neither about physical activity. Several authors [16] reported a positive and significant correlation between physical activity during pregnancy and good quality of life. Aerobic exercise during pregnancy contributes to positive feelings, reduces depression, and improves mood and well-being. Pregnancy planning was not questioned; Ali [25] points out that unwanted pregnancy is related to the health status of pregnant women.

It is recommended that the authorities who dictate health policies should keep in mind that pregnant women's care must be comprehensive and multidisciplinary [4]. Prenatal care protocols should provide guidelines for intervention on obstetric and non-obstetric factors that impair quality of life. It is necessary to emphasize that there are deficiencies in exploring pregnant women's mental, social, and environmental health. However, it has been identified as having a negative impact on maternal, fetal, and neonatal health [3, 5, 8, 10, 11, 17].

5. CONCLUSIONS

In a group of pregnant women from the Colombian Caribbean who attended a prenatal consultation and could continue with their regular activities, half presented deterioration of physical, psychological, social, and environmental health. Having a previous diagnosis of depression, feeling distressed or worried about pregnancy, having economic problems or relationship conflicts, or suffering from diabetes mellitus, were associated with impairment of any of the health domains. Living in rural areas was associated with deterioration in the four quality of life domains of the WHOQOL-BREF scale.

ACKNOWLEGEMENTS

To all patients who agreed to fill out the study forms. To Mabel Vergara Borja, for the supervision and logistics work. To the nursing staff and administrative officials of the care center chosen to carry out the study (Santa Cruz de Bocagrande Clinic, Cartagena, Colombia). To Mileydis Barrios Jiménez, for supervision and logistics work in the rural area.