INTRODUCTION

Osteoporosis is considered to be a public health problem characterized by low bone density and reduced bone quality through the deterioration of bone microarchitecture 1. As a consequence, sufferers have an increased susceptibility to osteoporotic fractures 2. Osteoporosis is a multifactorial and complex disease determined by both genetic and environmental factors 3.

Oxidative stress and low serum levels of antioxidants have been proposed to be contributors to osteoporosis. In vitro and animal studies have shown that oxidative stress could induce bone loss by modulating osteoclast activation and osteoblast suppression 4) (5) (6) (7. In this line, a number of epidemiologic studies have reported positive associations between oxidative stress and bone mineral density (BMD) 8) (9.

Evidence suggests that intake of antioxidants could positively influence bone mass by preventing bone metabolism against oxidative stress. Previous studies have investigated a relationship between antioxidants intake and BMD, fracture risk and osteoporosis reporting contradictory results 10) (11) (12) (13) (14. Most studies generally analyzed the association between single antioxidant intake and bone status. Little is yet known regarding diet quality indexes of antioxidant intakes and their potential relation with bone status. However, people consume foods with complex combinations of antioxidant nutrients 15 and therefore, this traditional approach misses information regarding interactions between different antioxidant contained in food.

Quantitative ultrasound (QUS) has been proposed as an alternative method to assess bone mass and provides parameters of bone structure (microstructure, elasticity and connectivity) 16. The QUS has been valued for its high correlation with BMD measured by DXA 17. Its portability, non-invasiveness, radiation-free and low cost nature make it a useful method for assessing bone status 18. Until now, no studies have examined the relationship between antioxidant intakes and bone mass assessed by QUS. Therefore, the aim of the current study was to investigate the influence of single antioxidant intakes and dietary antioxidant quality score (DAQs) on calcaneal QUS in young adults. We hypothesized that a high-quality antioxidant intake would be associated with a greater calcaneal QUS parameter.

METHODS

SUBJECTS

Six hundred and five individuals aged 18 to 25 (69.3% females and 30.7% males) agreed to participate in this study and were recruited from different academic centers of Granada (Spain). All participants were evaluated by means of a detailed medical history. Subjects with any of the following criteria were excluded from the study: history of bone disease, metabolic or endocrine diseases, hormone-replacement therapy or current treatments that could affect bone mass. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant and the study was approved by local ethics committees and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

ANTHROPOMETRIC MEASUREMENTS

Body weight (kg) and fat mass (%) were measured twice (without shoes and in light clothes) to the nearest 0.11 kg by bioelectrical impedance analysis (TANITA BC-418MA(r)). A Harpenden stadiometer (Holtain 602VR(r)) was used for height measurements. Height was measured twice without shoes to the nearest 0.5 cm. The averages of the two values for each measurement were used in the analysis. Anthropometric measurements were performed in the morning after a 12-h fast and 24-h abstention from exercise. BMI was calculated as weight over height squared (kg/m2).

CALCANEAL QUS

Bone mass status was measured by ultrasonography at the right calcaneus (BUA, dB/MHz) using the CUBA clinical ultrasound bone densitometer (McCue Ultrasonics Limited, Compton, Winchester, UK). The calcaneus is used for QUS assessment because it contains a high percentage of trabecular bone and it is easily accessible 19. Daily calibrations were made with physical phantom to control the long-term stability of the apparatus.

DAILY NUTRIENT INTAKE

Daily nutrient intake was assessed by a 72-hour diet recall interview considering intakes on Thursday, Friday and Saturday to capture weekly variations in weekdays and weekend. In a face-to-face interview with well-trained investigators, individuals were asked to recall all food consumed in the preceding 72 hours, including foods eaten outside the home, nutrition supplements and beverages. In order to improve the accuracy of the descriptions of meals, pictorial food models were employed. A computerized food analysis program (Nutriber 1.1.5) was used to assess completed food records 20. The food composition table reported by Mataix et al. was used for conversion of food into nutrients 21.

PHYSICAL ACTIVITY

Physical activity was assessed using a self-administered questionnaire (International Physical Activity Questionnaire-IPAQ). The questionnaire has proven to be a valid instrument for measuring PA in the European adult population 22. It was used to calculate the total hours of vigorous PA, moderate PA and walking over the last seven days. A MET-h was derived by multiplying the respective total hours by the metabolic equivalent of task (MET) value for vigorous PA (MET = 8.0), moderate PA (4.0) and walking (3.3), and then adding all three 22.

ANTIOXIDANT NUTRIENT INTAKE

A DAQs was used to calculate antioxidant nutrients 23. The test score assessed the consumption of vitamin C, vitamin E, vitamin A, selenium and zinc. Daily nutrient intake was compared to that of the daily recommended intake for the Spanish population (RDI) 24. When the nutrient intake was below 2/3 of the RDI, a value of 0 was obtained, and when the intake was above 2/3 of the RDI, a value of 1 was obtained. DAQs is scored with a final score range from 0 (very poor quality) to 5 (high quality).

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

SPSS Statistic version 21.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all the analyses. Mean and standard deviation (SD) where normally distributed and as median (interquartile range) where skewed are given as descriptive statistics. Sex-specific differences were assessed by independent t-test. Sperman's correlation coefficient (r) was used to test the correlation between antioxidant nutrients, DAQs and calcaneus QUS adjusted by age, body weight, height, calcium intake and physical activity. To analyze the associations between single antioxidants intake, DAQs and calcaneus QUS, multiple regression analysis was performed after adjusting by age, body weight, height, calcium intake and physical activity. Results are reported as standardized β-coefficient, R, R2, adjusted R2, t and p value. p-values < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

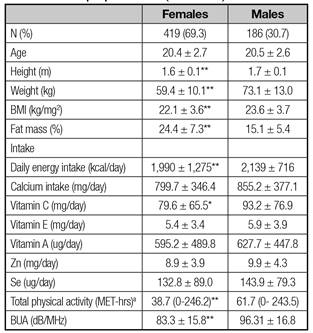

The basic characteristics were summarized separately for men and women in table I. The mean age for the study population was 20.4 ± 2.7, and the mean BMI was 22.6 ± 3.7 kg/m2. Significant differences between men and women were observed in height, weight, BMI, fat mass, physical activity and BUA values. Men had a significantly higher body height, weight, and BMI than women (p < 0.001), whereas women had a significantly higher fat mass than men (p < 0.001). The reported energy intake was higher in men than in women, but there was no evidence of any significant differences. Average calcium intake was below the recommended intake level (RDA) in both genders. The mean calcaneus BUA for the sample was 86.7 ± 17.6 (dB/MHz) and males had a significantly higher BUA than females (p < 0.001). Regarding the intake of antioxidant nutrients, the average intakes of vitamin E, vitamin A and zinc were lower than the recommended in both sexes. By contrast, the intake of vitamin C and selenium reached the dietary goals. Considering gender, a significant difference has been observed concerning the intake of vitamin C (p = 0.036).

Table I Basic characteristics of the study population (n = 605)

Data are shown as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05 between females and males; **p < 0.001 between females and males. All the nutrients were adjusted for energy intake. BMI: Body mass index mineral; MET: Metabolic equivalent of a task, representing energy expenditure per day. aMET-hrs are expressed as mean and range.

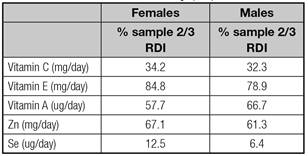

The percentages of young adults that are below 2/3 of the RDI for antioxidant nutrients are shown in table II. Regarding vitamin E, a higher percentage of women and men had inadequate antioxidant intake (defined as intakes below 2/3 of the DRI). As can be observed, most women were low antioxidant consumers (only 17.6% of women had a score of 4 or 5 in DAQs). In this line, only 20.3% of men showed a high-quality antioxidant intake (DAQs 4 or 5).

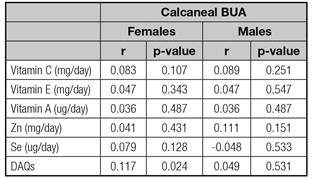

Sperman's correlation revealed a positive relationship between DAQs and calcaneus BUA in women (r = 0.117; p = 0.024) (Table III). In order to analyze the influence of DAQs and each antioxidants intake on calcaneal QUS, multiple regression models were applied after adjusting by body weight, height, calcium intake and physical activity (Table IV). Interestingly, the multiple regression analysis revealed that DAQs was significantly associated with BUA parameter in women (p = 0.035). No significant associations between single antioxidant nutrient and calcaneus QUS measurement were found.

Table III Spearman correlation coefficients (r) between antioxidant nutrients, DAQs and calcaneal QUS

DAQs: Dietary antioxidant quality score. Adjusted by age, weight, height, calcium intake and physical activity.

DISCUSSION

The present study explores the associations between DAQs and single antioxidant intakes on calcaneal QUS measurement in a sample of 605 young adults. Our findings provide evidence for the influence of DAQs on calcaneal BUA parameter in young women, supporting the hypothesis that a high-quality antioxidant intake could positively influence bone mass in young women. To our knowledge, there has been no previous study investigating the association of DAQs on bone mass assessed by calcaneal QUS measurement.

To date, only two studies have investigated the association between DAQs and bone status 11) (12. In agreement with our findings, Rivas et al. reported a significant positive association between DAQs and BMD among 280 healthy women aged 18 to > 45 (p = 0.021) 12. On the other hand, in the study of De França et al., 150 postmenopausal women over 45 years old with osteoporosis were included 11. In contrast to Rivas et al. and with our findings, any relationship was found between DAQs and BMD in any skeletal sites. One possible reason for this discrepancy may be attributed to the limited sample size or to the sample consisting of osteoporotic women. DAQs could not be suitable for assessing the association of antioxidant dietary intakes and bone mass in osteoporotic subjects since the antioxidant considered in this score could have a minimum effect on low BMD values. In addition, in this study they applied an adaption of the original DAQs since they used estimated averages requirements (EAR) instead of RDI. It should be noted that both previous studies used DXA for measurements of bone mass, none of them used calcaneal ultrasound, and hence, we could not compare our effect sizes for BUA.

This study is the first one to explore the association of DAQs with bone mass in a population of men. Although our study reported a lack of association, we cannot completely discard an association of DAQs with bone mass in men due to the relatively small sample size compared to that of women. Further studies including larger samples are required to assess the relationship between DAQs and bone mass in men.

In this study, when antioxidant nutrient intakes were analyzed separately, any association between single antioxidants and calcaneus QUS was observed. Previous studies have assessed the association between select dietary antioxidants, vitamin C 10) (14) (25) (26) (27) (28, vitamin E 14) (29, vitamin A 14) (30) (31) (32, zinc 33 and selenium 14) (29) (34 and bone mass, revealing inconsistent findings. One possible cause of inconclusive results could be differences in sample sizes and characteristics, study designs and dietary assessments among studies. It must be highlighted that these studies have focused on the effects of single antioxidants on bone health. By using this approach, potential interactions among different antioxidant dietary intakes have been ignored because people consume food with a complex combination of antioxidants, rather than single antioxidants. Consequently, in order to analyze the effect of overall diet and detect possible interactions, recent studies are using diet quality indexes as an alternative method 10) (35) (36.

The current study has a larger sample size than previous studies exploring the association of DAQs and bone mass. Moreover, this study provides the first investigation of DAQs and bone health in both men and women. Furthermore, all analyses were adjusted for relevant covariates known to affect bone mass. One limitation of our study was its cross-sectional design, from which causality could not be inferred. Another limitation is inherent to the assessment of dietary intake using a self-administered questionnaire. The literature supports the use of 72-hour recall as a pertinent method for assessing nutrient intake since it collects better data on the typical or average diet 37. However, evidence of underreporting of food intake in self-administered questionnaires has been reported previously 37) (38. In our study the 72-hour recall was interviewer-driven. Additionally, well-trained investigators asked study subjects to recall all food intakes and, in order to improve the accuracy of the descriptions of meals, pictorial food models were employed. Another potential limitation is the lack of data regarding the culinary treatments that might influence on the reported intake of antioxidants. Finally, the effect of other antioxidants such as flavonoids was not considered.

In summary, our findings of significant associations between DAQs and calcaneal ultrasound in young women reflect the protective role of high-quality antioxidant intakes as an environmental factor contributing to bone health. Future studies should further explore the potential influence of antioxidant nutrients against osteoporosis.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS AND INFORMED CONSENT

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964 and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Written informed consent was obtained for all participants.