My SciELO

Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Anales de Psicología

On-line version ISSN 1695-2294Print version ISSN 0212-9728

Anal. Psicol. vol.32 n.1 Murcia Jan. 2016

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.32.1.202601

Styles Questionnaire of Interaction between Parents and Practitioners in Early Intervention: content validity

Cuestionario de estilos de interacción entre padres y profesionales en atención temprana: validez de contenido

Claudia Tatiana Escorcia-Mora1, Francisco Alberto García-Sánchez2, María Cristina Sánchez-López2 and Encarnación Hernández-Pérez2

1 Grupo de Investigación en Educación, Diversidad y Calidad. Dpto. de Psicología y NEE. Universidad Católica de Valencia. (Spain).

2 Grupo de Investigación en Educación, Diversidad y Calidad. Dpto. Métodos de Investigación y Diagnóstico en Educación. Facultad de Educación. Universidad de Murcia. (Spain).

Work funded by the National Plan for Scientific Research, Development and Technological Innovation (I + D + i) (Spain). Project number: EDU2010-17786.

ABSTRACT

Nowadays, Early Childhood Intervention in Spain is taking interest in a family-centred approach. In this context, we present the Styles Questionnaire of Interaction between Parents and Practitioners in Early Intervention -known as SIPPEI (EIPPAT). This is a tool to identify actions, practices and interaction styles conducted by the practitioner to guide families (participative and relational practices). This paper shows the items set of the aforementioned Questionnaire -versions for practitioners and caregivers. Formerly, we detailed the hard work and effort invested to ensure content validity, as we had two focus group -consisting of 15 professionals and 11 parents) and a systematized expert judgment by 11 professionals and 5 mothers. Subsequently, an implementation of the questionnaire was developed by a group of 41 practitioners in order to assess the importance given to the items. The results show that the procedure followed to create the questionnaire accomplishes the main objectives. Thus, we got a questionnaire highly regarded by professionals in this area.

Key words: Early Childhood Intervention; family; family-centred services; parents-professionals relationship.

RESUMEN

En un momento en el que, la atención Temprana en España, esta empezando a interesarse por el enfoque centrado en la familia, presentamos el Cuestionario de Estilos de Interacción entre Padres y Profesionales en atención Temprana (EIPPAT). Un instrumento que permite identificar el grado de implementación de diferentes actuaciones, prácticas y estilos de interacción llevadas a cabo por el profesional de atención Temprana para orientar a las familias (prácticas relacionales y participativas). El trabajo presenta los ítems del EIPPAT, en sus versiones para profesionales y cuidadores principales del niño. Previo a ello, detalla los esfuerzos realizados para asegurar su validez de contenido: dos grupos focales de discusión (conformados por 15 profesionales y 11 padres/madres), que posibilitasen la construcción inicial del instrumento; un juicio de expertos sistematizado (11 profesionales y 5 madres); y una aplicación del EIPPAT, para la valoración de la importancia otorgada a sus ítems, por un grupo de 41 profesionales en ejercicio. Los resultados evidencian que el procedimiento seguido para la elaboración del instrumento cubre sus objetivos, disponiendo de un cuestionario altamente valorado por los profesionales en las dimensiones que evalúa.

Palabras clave: atención Temprana; familia; servicio centrado en la familia; relación padres-profesionales.

Introduction

Early Intervention is a rather new field which has just five decades of history. There is a consensus on placing its origins in the 60s in the United States (Bailey, Aytch, Odom, Symons & Wolery, 1999; Milla, 2005; Ramey & Ramey, 1998; Shonkoff & Meisels, 1990). Therefore, we are living changes aimed to improve Early Intervention practices, adjusting them to people's needs and to the substantive body of evidence demonstrated (Dunst, Trivette & Hamby, 2007).

Since the 90s in the United States (Odom & Wolery, 2003) and later in Europe, a progressive approach has been being developed internationally, to a family-centred practice (Espe-Sherwindt, 2008; Dunst 2000; Soriano & Kyriazopoulou, 2010). This approach promotes changes in the roles played by the practitioners and families, in the way practitioners use their knowledge, and in how practitioners pose to families the decisions about the objectives to achieve (Dunst, Johanson , Trivette & Hamby, 1991; Espe-Sherwindt, 2008; García-Sánchez, Escorcia-Mora, Sánchez-López, Orcajada & Hernández-Pérez, 2014). From this family-centred practice, practitioners consider families as equal partners and necessary collaborators to get support and enhance child's development. The Intervention is always individualized, flexible and responsive to each child and family needs. Early interventionist does not identify these needs, but rather families and practitioners working together. Family involvement and partnership are their working goals. Therefore, families are highly involved in Early Intervention practices; and professional intervention focuses on strengthening and supporting family functioning, especially creating learning opportunities for children which are contextually mediated. Hence, practitioners should take care families misunderstand their role, as they must not act as a practitioner at home. To achieve these objectives and the essential involvement, motivation and support of families, practitioners constantly care about families being who make decisions as a planned strategy to enhance their competence, support and commitment to the actions to be carried out.

Taking care of family needs requires specialized work by the Early Childhood practitioner. Consequently, the professional must be provided, among other skills, with an extensive knowledge to understand the personal and family dynamics, and a personal disposition to facilitate family motivation and empower the monitoring of the guidelines provided. Likewise, early intervention practitioner should be aware of communication and information strategies as a help (Knoche, Kuhn & Eum, 2013). Nowadays, we need a new deep professionalization about early interventionist action into Early Intervention Centre.

Until now, in our country most of the developed practices have remained largely oblivious to this approach focused on the family.

In the 80s, while Early Intervention increased in Spain, the effectiveness of therapist-family model was being questioned around the world since parents were sacrificing their natural roles, in exchange for a transformation in pseudotherapists (Espe-Sherwindt, 2008; García-Sánchez et al., 2014). As a consequence, a therapist-expert modified model was established based on some family counselling in Spain.

In our country, the involvement of families, working together in the child's natural environment, has remarkably appeared in the Paper White on Early Intervention (GAT, 2000), in subsequent documents of the State Federation of Early Intervention Professionals (GAT, 2005) and in other papers (De Linares & Rodríguez, 2005; Díez-Martínez, 2008; Perpiñan, 2009; Mendieta, 2005; Castellanos, García-Sánchez, Mendieta & Gómez-Rico, 2003; García-Sánchez, 2002a, 2002b, 2003). However, several authors have pointed out the need to continue evolving towards a more active family involvement in Early Intervention (Giné et al., 2006; García-Sánchez et al., 2014; Gutiez, 2010). It is where one of the major differences between this approach and others resides in.

Multiple studies (Dempsey & Dunst, 2004; Dunst, Boyd, Trivette & Hamby, 2002; Dunst, Trivette & Hamby, 2007; Espe-Sherwindt, 2008; García-Sánchez et al., 2014), have identified two related, but distinctly, components of family-centred practice -'relational practices' and 'participative practices'. The former are made up of those interpersonal behaviours such as cordiality, active listening, empathy, authenticity and of parents view from a positive view. These kind of dynamics is used by professionals to build effective relationships with families and promote working alliance.

Participatory practices, on the other hand, are more directed to encompass action, control and sharing: professionals share all information with families. Here is where the main difference among Early Intervention approaches is. In this context, practitioners encourage parents to make their own decisions, persuade them to use their existing knowledge and capabilities, and help them learn new skills.

Consequently, we will able to promote the necessary change that is being demanded from the European Association on Early Childhood Intervention (EURLYAID) and from the European Agency for Development in Special Needs Education (Pretis, 2010; Soriano, 2000; Soriano & Kyriazopoulou, 2010). The necessary change that is being demanded should be based on evidence. Consequently, nowadays, we need tools to understand the practices carried out, and to assess the skills Early Intervention includes with practitioners in their interactions with family. Generally, the survey is used in the Education and Social Sciences field. It is a highly useful tool to research problems, which enables the collection of diverse information about a large number of variables (Martín, 2010) and their transformation into empirical variables, about which to collect data (in our case, actions taken to provide guidance, difficulties, personal style to communicate, etc.) in specific questions, generating reliable, valid and sensitive responses to be quantified (Casas, Repullo & Donated, 2003).

The goal of this paper is to present the Styles Questionnaire of Interaction between Parents and Professionals in Early Intervention (SIPPEI). It was designed to assess how the relationships between professionals/practitioners and caregivers are built, the level of implementation of participatory and relational practices in Early Intervention, and the procedure followed to ensure content validity.

Method

Participants

We had three groups of participants in our study: focus groups, an expert judgment and a professionals group who assessed the item set importance.

Focus Groups

Two focus group discussions were organized. The goal was to create some draft items set to include into the questionnaire. The first one was integrated by Early Intervention practitioners, and the second one was constituted by parents, whose children needed Early Intervention, and primary caregivers.

The practitioners' focus group had 15 participants, all of them were women. Five of them were Psychologists and Speech Therapists; other five were only Speech Therapists; two were Educators (one of them was Speech Therapist, too); two were Occupational Therapists, and one was Special Education Teacher. All of them were working in an Early Intervention Centre in the region of Valencia: eleven practitioners were from that region, and the rest of them were from Castellon. These practitioners worked in four community centres, three centres which were dependent on parents associations, one dependent on Health Ministry, and another dependent on other institutions. They were aged between 26-56, being most of them -62%- between 30 and 45 years old. The professional experience in Early Intervention ranged from 3-25 years, with an average of 8.6 years (SD: 6.11).

In the families' focus group, 13 parents were involved (five fathers and eight mothers), whose children received Early Intervention services in Castellon (4 families) and Valencia (9 families). Practitioners' participants were from the Early Intervention Centres previously mentioned.

Through the practitioners, we conducted a non-probability and purposive sampling to select the families. Participants were voluntarily informed. Some rules were compulsory:

a. To be the primary caregiver of a child who had Early Intervention needs.

b. To have started the Early Intervention three months before.

c. Do not suffer from a physical or mental condition that prevents participation or attendance to the focus group.

d. Ability to communicate in Spanish and/or Valencian.

Regarding the children, they were requested to have communication and language disorders or difficulties, due to the fact that this kind of problems needs more guidance from families and caregivers. We chose these selection criterions due to these disorders or difficulties must involve family guidance and the participation of family is crucial for enhancing children languages skills. Children whose families were participants had a wide variety of problems: Autism / Pervasive Developmental Disorder (4 cases), Infant Cerebral Palsy (2 cases), Down Syndrome (2 cases), DiGeorge Syndrome (1 case) and Angelman Syndrome (1 case).

Expert judgment

To carry out the expert judgement, which were assessed original items, we count on the collaboration of sixteen participants: eleven practitioners and five mothers whose children needed Early Intervention.

From this group, six were Psychologists who worked in Early Intervention, with an experience higher than 23 years on the field. Five were Educators who were specialized in Guidance. They knew about the Early Intervention discipline and they were involved in research about this area. They had an experience of around 22 years.

The five mothers who acted as experts were selected through a non-probability and purposive sampling. Two people responsible into Early Intervention centres gave questionnaires to families. Once questionnaires were replied, they collected them. Mothers were aged between 33 and 38 years old (Mean= 35.4 years). Four of them had a University Degree and the last one had Professional Training. All of them had been actively involved in Early Intervention programs for their children. Their children had been in Early Intervention Centre since birth (3 cases), since they were 10 months old (1 case) and 20 months old (1 case). They suffered from some Plurimalformative Syndromes (3 cases), Encephalopathy, Fragile X Syndrome and Nemaline Myopathy.

SIPPEI Questionnaire items' assessment by professionals

Forty-one (41) Early Intervention practitioners, who worked in Early Intervention Centres (ASTRAPACE, Murcia; ASTUS Virgen de la Caridad, Cartagena and AIDEMAR, San Javier), participated.

Table 1 summarizes key socio-demographic characteristics.

The group was mostly comprised of women (95%) between 24 and 56 years old. 60% of participants were in an age range between 30 and 45 years. 71.05% of practitioners had experience in Early Intervention over 6 years (18.4%, over 25 years).

With regard to professional profile, we found Speech Therapists (23.1%), Physical Therapists (30.8%), Psychologists (23.1%), Educators (2.6%) and Stimulation Therapists (23.1%). 52.5% of practitioners had specialized training after their initial training: Master's Degree in Early Childhood (47.4%), training courses (31.6%) and other studies (21.1%).

24.3% of professionals had some charge of responsibility in the Early Intervention Centre: Management or Organization in the Early Intervention Centre. Four of them were technician coordinators, two of them were managers of the Early Intervention Centre and another one was a person in charge of Nurseries School Coordination.

Procedure

Focus groups

Once participants were selected, each focus group was independently convened. While carrying out, an observer and a moderator/facilitator were present. The facilitator's goal was redeploy when it was necessary. In the practitioners' focus group, the facilitator was an Occupational Therapist, working as a university professor with twelve years of experience in Early Intervention and team management. In the families' focus group, the facilitator was a Psychologist with 10 years of experience (six of them in Early Intervention). She was a university professor and an expert in conflict resolution. The observer role was played by a Speech Therapist, who works as a university professor and with an experience of about 24 years (12 years in Early Intervention area).

The sessions were held in the Speech Therapists College of Valencia (practitioners group) and in a classroom at the Catholic University of Valencia (family group). It lasted around 120 and 150 minutes. The whole meeting was audio recorded and later transcribed for analysis.

Expert Judgment

Professionals rated the items set (two versions). They were provided with a specifically designed tool which was completed independently. Similarly, the family's group assessed the item set designed to be distributed to the primary caregivers.

We also requested some suggestions and recommendations to improve the original items set. There were gaps enabled to collect that. Professionals had to evaluate the applicability of the questionnaire title, the accuracy and conciseness of the items about socio-demographic variables, the inclusion or exclusion of any item if convenient.

SIPPEI Questionnaire items' assessment by professionals

Firstly, to apply the Questionnaire (professionals version), we contacted with the management or coordination services into Early Intervention Centres. We explained our purpose to the Management/Organization professionals. Once they decided to help us, some copies of the Questionnaire were sent; after the established period of time, we contacted again to collect the completed Questionnaires.

Instruments

Focus groups

The focus groups' facilitator had a brief script, to encourage potential topics to discuss. These questions were used only when it was deemed necessary to refocus the discussion. Table 2 lists the questions collected.

Focus Groups Meetings were recorded through two digital tape recorders (SONY ICD-UX200 de 2Gb). They were placed into opposite side table or room.

Expert Judgment

To collect the expert judgment's assessment (two versions of the SIPPEI Questionnaire), a specific instrument for review and validation was prepared. Six dimensions byproduct of focus groups were thoroughly explained. This tool explained the main goal, the six dimensions -from the focus groups' results-, and the assessment process. Professionals had to evaluate the overall items through a 5-point Likert item (1-None; 2-Slight; 3-Enough; 4-Quite; 5-Total). Overall items had to be assessed according to two levels: clarity degree (understandable and unambiguous wording) and representation degree (suitability for the dimension where included).

SIPPEI Questionnaire items' assessment by professionals

The SIPPEI Questionnaire -in both versions (caregivers and professionals)- is divided into two sections. The first one includes socio-demographic data about the primary caregiver identification (gender, age, kinship to the child, attendance at Early Intervention Centre, education, occupation, marital status, nationality, and common language) and the child (age, gender, number of siblings, kind of treatment, disability and attendance time at Early Intervention Centre) or the professional (gender, professional profile, experience work, specialized training, responsibility charge: Management or Organization).

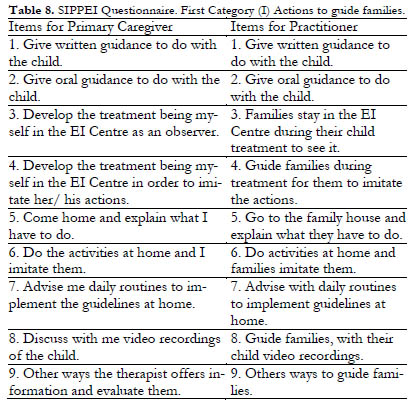

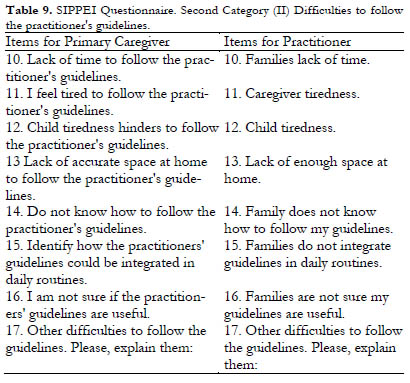

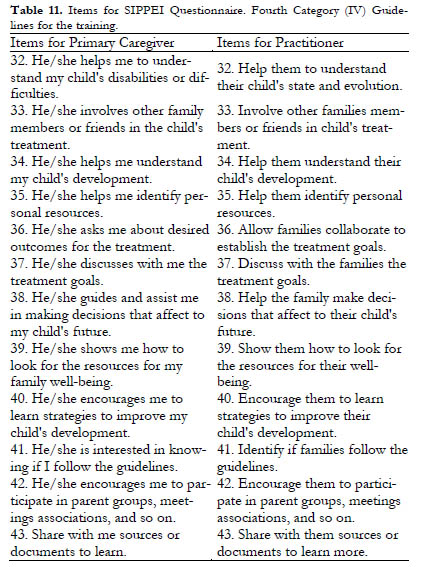

The second section includes forty-one 5-point Likert item, assessing a time criterion (1. Never; 2. Rarely; 3. Sometimes; 4. Almost always; 5. Always). There are also two free-answer items. Overall items rate four practitioners and family relationships' categories in Early Intervention: (I) Actions taken to provide family guidance (8 Likert-items and one free-answer item); (II) Difficulties to follow the guidelines (7 Likert-items and one free-answer item); (III) Practitioner personal style to give guidance (14 items); and (IV) Guidelines for training (12 items).

The original SIPPEI Questionnaire -practitioner's version- was modified to include a second level response (regarding importance level). Each item had to be assessed based on its importance degree (1. Not important 2. Little important 3. More or less important, 4.Quite important 5. Very important).

Results

Focus groups

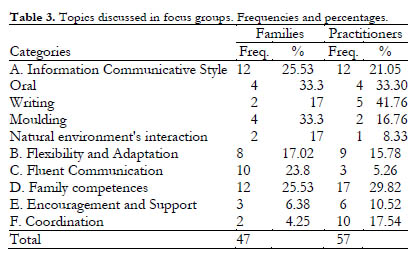

Table 3 presents the categories about relevant topics in practitioners and families relationships, as a result of the focus groups.

Family Competence is the most repeated discussion topic, both among family members (25.53%) and, especially, among professionals (29.82%). Information communicative styles are the second topic, more discussed in families (25.53%) than among professionals (21.05%). Regarding to Interaction Style, families debated most frequently about oral communication and modelling (33.3%). Nevertheless, professionals most frequently discussed on the information communication through written documents (41.76%) and orally (33.3%).

The topic less frequently discussed by practitioners is Fluent Communication (5.26%). This category is regarded with the practitioner's ability to generate a confident climate, closeness and respect with the families. It appeared most frequently into family groups than professionals groups. By contrast, families discussed most often about this topic than practitioners (23.38%). On the other hand, families rarely discussed (4.25%) about the Coordination with professionals in nursery schools, while professionals debated more often about that topic (17.54%).

By-product these information categories, which were identified through focus groups and according to the relevant literature reviewed, the items were written, adapted to each versión. The Questionnaire structure is summarized in Table 4.

Expert's Judgment

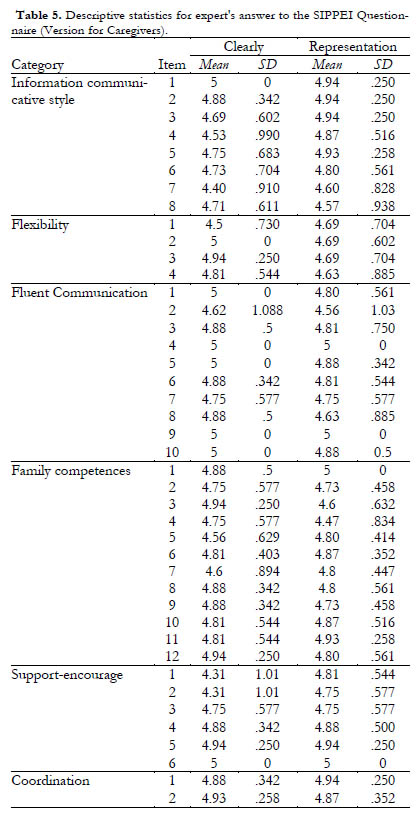

Means and Standard Deviations (SD) from Questionnaire's items are shown in Table 5. It shows caregiver's version according to proper composition level and their representation level for every category.

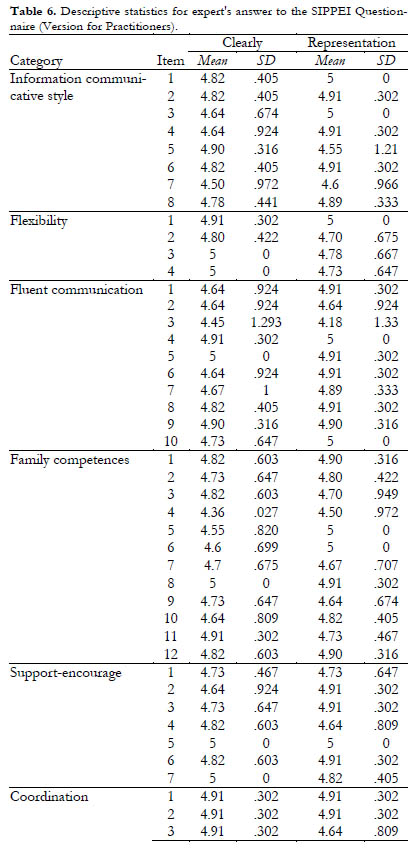

Table 6 shows Means and Standard Deviations (SD) from Questionnaire's items (version for Practitioners).

According to the results, the original items set was reconsidered. We decided to delete the items whose mean was 4.88 points or lower (versión for Caregivers, which was assessed by sixteen judges), and 4.82 points or lower (versión for Practitioners which was assessed by eleven judges). In both cases, we rethink the item or its original writing when two experts give 4 points or one of them gives 3 points. In addition, all free annotations were considered.

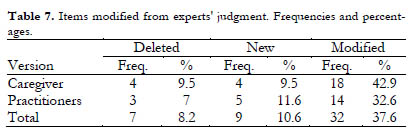

Table 7 summarizes the volume of deleted items, new items or redrafting items from expert judgment.

Through expert's assessment the original categories were reformulated, reducing them from six to four: (I) Actions taken to provide family guidance; (II) Difficulties to follow the guidelines; (III) Professional personal style to give guidance and (IV) Guidelines for training. Both versions of the Questionnaire were comprised of 43 items -similar content, each one adapted in writing to their recipients). Previously, socio-demographic questions were prepared about the primary caregiver and the child characteristics -in one case-, and about the practitioners' -in the other one-.

Tables 8 to 11 Items (both versions of SIPPEI Questionnaire) are shown for each of the final categories.

SIPPEI Questionnaire items' assessment by professionals

Professionals' opinion about the items set is presented in Table 12. They were asking for importance level, which they awarded to questionnaire items.

In the first category (I), the three lowest-average items are about the Visits to the family residence (Items 5 and 6) and the resource of video recordings to guide families (Item 8). In the second category (II), the item rated with the least important is number 13. It is focused on the lack of adequate space at home to follow the guidelines. Item 10, based on the lack of time in families, is also rated low. In third category (III), all the items are marked with a very high average. The lowest mark is for Item 30, which refers to flexibility in home visits.

Finally, in the fourth category (IV) means are also incredibly high. The lowest mark is found in Item 36, based on involvement of the family in establishing treatment goals. It is followed by Item 33, focused on other member's involvement -close to the child- in treatment.

Discussion and conclusions

In this paper, we showed the Styles Questionnaire of Interaction between Parents and Practitioners in Early Intervention (SIPPEI). In this context, it is a useful tool for practitioners' self-assessment, and for team assessment in the relationship between families and practitioners. We describe the way the questionnaire was created.

The questionnaire was developed to assess a variety of specific actions and practices which help to improve family's motivation and involvement, and adherence to the practitioners' guidelines. Therefore, the SIPPEI questionnaire is an accurate tool to analyze the resources and the practitioner's actions from a family-centred approach. Specially when the categories help to assess the implementation of both Relational and Participative practices, being the latter an important point for this (Depmsey & Dunst, 2004; Dunst et al., 2002, Espe-Sherwindt, 2008; García-Sánchez et al., 2014).

The first item set assessed, simultaneously, how information is shared with family and how family is involved and how this collaboration is organised (participative practices implementation). This item set reflects family-centred practices or nearness towards this approach, depend on guidelines would be more or less managerial. The second item set focuses on finding difficulties in following practitioner's guidance (concerning difficulties which could obstruct family duties). The third item set evaluates relational practices, while the fourth one continues assessing participative practices. It evaluates caregivers' competences and other members' abilities (people who live in the child's natural environment).

To achieve content validity of the items designed for the SIPPEI Questionnaire, we used different redundant and methodological processes.

Firstly, we used focus groups. They provided an opportunity to get close to a family-centred practice, approach that is not being found in most of the international literature (Dunst et al., 2007; Espe-Sherwinidt 2008; Odom & Wolery, 2003; Soriano & Kyriazopoulou, 2010). There is a consensus, into scientific community, that focus groups are a useful way to get information and describe a phenomenon. In addition, focus groups are available to analyse and explore joints, fairly steady, among own features; through a systematic observation (Escobar & Bonilla-Jiménez, 2009).

The focus group's work allowed identifying the main item sets. As a result, we started our items design. This methodological technique made possible analyzing factors which favour or complicate an effective relationship between families and practitioners. Furthermore, it helped to find professionals' strategies to share information with families.

As a result of these groups, we conducted an initial descriptive study where we collected the communication strategies, especially which had been used by Speech and Stimulation Therapists to share their recommendations to families in Early Intervention Centres in Valencia. Additionally, the families' feelings were analyzed regarding the relationships with practitioners, and when they receive information and recommendations about their children treatment.

Within their results, some qualitative differences have been found, interesting to understand the current situation which we are living. Families, in their meetings, paid less attention to some practices, such as written guidelines submission or coordination. On the other hand, they were more interested in the interaction and communication with practitioners in natural environments. Nevertheless, practitioners did just the opposite. Additionally, in their meetings, family spent more time to Fluent Communication. Nonetheless, they spent less time to Coordination category.

According to the relevant reviewed literature and the analysis of the six constructs identified in the focus groups (sharing information styles, flexibility, fluent communication, family responsibilities, helping-stimulating and coordination), the prototype for the SIPPEI Questionnaire was created. It had two versions: for caregivers and for practitioners.

It was subjected to a rigorous expert judgment, which allowed improving the original questionnaire. The items (sets) and their categories were defined more accurately, (items and categories for the definitive version). We deem expert judgment's technique quite positive, when it is precisely directed. In this way, judges can assess specific features where their opinion is especially relevant.

Involving in an expert judgment, besides the practitioners and also families, meets our requirements and point of view: family, as an active agent of change (García-Sánchez, 2002a, 2002b; Wilson & Dunst, 2006), is largely coresponsible for treatment (Perpiñán, 2009, 2003a, 2003b) and, therefore, their opinion has to be listened.

After the expert's judgment, we already had an operational questionnaire. Nevertheless, we required to ensure the questionnaire's content validity. Thus, we enquired a great number of experienced professionals about the importance given to the original items set. The conclusion was quite satisfactory. The items were rated with high marks. It is interesting that the items which received a lower mark were focused on the family-centred model (e.g. 'go to the family residence', 'child's natural environment and characteristics/concerns', 'family involvement',...). Precisely, these items are required to be incorporated (García-Sánchez et al., 2014; Giné et al., 2006; Gutiez, 2010; Pretis, 2010; Soriano, 2000; Soriano and Kyriazopoulou, 2010).

Therefore, we conclude that the Questionnaire we developed could identify interaction styles and relational and participatory practices between practitioners and families in Early Intervention. It is a useful tool both for professional's self-assessment or for more globalised researches about Early Intervention services. This is a tool to analyse strengths and weakness from services. Through them, once practitioners and caregivers opinions are corroborated, we will be ready to provide improvement suggestions.

Next studies will help us to improve the original Questionnaire, its validity, overcoming some limitations found in this case. For that reason, it could be interesting to apply the Questionnaire to broader population groups, with diverse social and regional realities.

References

1. Bailey, D. B., Aytch, L. S., Odom, S. L., Symons, F. & Wolery, M. (1999). Early intervention as we know it. Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 5, 11-20. [ Links ]

2. Casas, J., Repullo, R. & Donado, D. (2003). La encuesta como técnica de investigación. Elaboración de cuestionario y tratamiento estadístico de los datos. Atención Primaria, 527-538. [ Links ]

3. Castellanos, P., García-Sánchez, F. A., Mendieta, P. & Gómez-Rico, M. D. (2003). Intervención sobre la familia desde la figura del terapeuta-tutor del niño con necesidad de atención Temprana. Siglo Cero. Revista española sobre Discapacidad Intelectual, 34(3), 5-18. [ Links ]

4. De Linares, C. & Rodríguez, T. (2005). La familia como sujeto agente en la actual concepción de la atención Temprana. In M. G. Millá & F. Mulas, Atención Temprana. Desarrollo Infantil, Trastornos e intervención (pp. 767-788). Valencia: Promolibro. [ Links ]

5. Dempsey, I. & Dunst, C. J. (2004). Helpgiving styles and parent empowerment in families with a young child with a disability. Joumal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 29(1), 40-51. [ Links ]

6. Díez-Martínez, A. (2008). Evolución del proceso de Atención Temprana a partir de la triada profesional-familia-niño. Revista Síndrome de Down, 25, 46-55. [ Links ]

7. Dunst, C. J. (2000). Revisiting Rethinking Early Intervention. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 20(2), 95-104. [ Links ]

8. Dunst, C.J., Boyd, K., Trivette, C.M. and Hamby, D.W. (2002). Family oriented program models and professional helpgiving practices. Family Relations, 51(3), 221-229. [ Links ]

9. Dunst, C. J., Johanson, Trivette, C. M. & Hamby, D. W. (1991). Family oriented early intervention policies and practices: family-centered or not? Exceptional Children, 58, 115-126. [ Links ]

10. Dunst, C. J., Trivette, C. M. & Hamby, D. W. (2007). Meta-analysis of family-centered helpgivmg practices research. Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 13, 370-378. doi:10.1002/mrdd.20176. [ Links ]

11. Escobar, J & Bonilla-Jiménez, F. (2009) Grupos focales: una guía conceptual y metodológica. Cuadernos Hispanoamericanos de Psicología, 9(1), 51-67. [ Links ]

12. Espe-Sherwindt, M. (2008). Family-centred practice: collaboration, competency and evidence. Supportfor Learning, 23(3), 136-143. [ Links ]

13. Grupo de Atención Temprana (2000). White Paper on Early Intervention. Madrid: Real Patronato sobre Discapacidad. [ Links ]

14. Grupo de Atención Temprana (2005). Recomendaciones técnicas para el desarrollo de la Atención Temprana. Madrid: Real Patronato sobre Discapacidad. [ Links ]

15. García-Sánchez, F. A. (2002a). Atención Temprana: elementos para el desarrollo de un Modelo lntegral de intervención. Bordón, 54(1), 39-52. [ Links ]

16. García-Sánchez, F. A. (2002b). Reflexiones sobre el futuro de la Atención Temprana desde un Modelo Integral de intervención. Siglo Cero. Revista española sobre Discapacidad Intelectual, 32(2), 5-14. [ Links ]

17. García-Sánchez, F. A. (2003). Objetivos de futuro de la Atención Temprana. Revista de Atención Temprana, 6(1), 32-37. [ Links ]

18. García-Sánchez, F. A., Escorcia-Mora, C. T., Sánchez-López, M. C., Orcajada, N. & Hernández-Pérez, E. (2014). Atención Temprana centrada en la familia. Siglo Cero. Revista española sobre Discapacidad Intelectual, 45(3), 6-27. [ Links ]

19. Giné, C., Gràcia, M., Vilaseca, R. & García-Díe, M. T. (2006). Repensar la atención temprana: propuestas para un desarrollo futuro. Infancia y Aprendizaje, 29(3), 297-313. [ Links ]

20. Gutiez, P. (2010). Early Childhood Intervention in Spain: standard needs and changes. International Journal of Early Childhood Special Education (INT-JECSE), 2(2), 136-148. [ Links ]

21. Knoche, L. L., Kuhn, M. & Eum, J. (2013). "More Time. More Showing. More helping. That's how it sticks": the perspectives of early childhood coachees. Infants and Young Children, 26(4), 349-365. [ Links ]

22. Martín, J. F. (2010). Técnicas de encuesta: cuestionario y entrevista. En S. Nieto (Ed.). Principios, métodos y técnicas esenciales para la investigación educativa. (pp.145-168). Madrid: Dykinson. [ Links ]

23. Mendieta, M. P. (2005). Intervención familiar en atención Temprana. In M. G. Millá & F. Mulas, Atención Temprana. Desarrollo Infantil, Trastornos e Intervención (pp. 789-806). Valencia: Promolibro. [ Links ]

24. Millá, M. G. (2005). Reseña histórica de la Atención Temprana. In M. G. Millá & F. Mulas, Atención Temprana. Desarrollo Infantil, Trastornos e Intervención (pp. 255-266). Valencia: Promolibro. [ Links ]

25. Odom, S. L. & Wolery, M. (2003). A Unified Theory of Practice in Early Intervention/Early Childhood Special Education: Evidence-Based Practices. The Journal of Special Education, 37(3), 164-173. doi:10.1177/00224669030370030601. [ Links ]

26. Perpiñán, S. (2003a). La intervención con familias en los programas de Atención Temprana. En I. Candel. (Dir.), Atención Temprana. Niños con síndrome de Down y otros problemas de desarrollo (pp. 57-79). Madrid: FEISD. [ Links ]

27. Perpiñán, S. (2003b). Generando entornos competentes. Padres, educadores, profesionales de Atención Temprana: un equipo de estimulación. Revista de Atención Temprana, 6(1), 11-17. [ Links ]

28. Perpiñán, S. (2009). Atención Temprana y Familia. Como intervenir creando entornos competentes. Madrid: Narcea. [ Links ]

29. Pretis, M. (2010). Early Childhood intervention across Europe. Towards standars, shared resources and national changes. Ankara, Turquía: Manfred Pretis. [ Links ]

30. Ramey, C. T. & Ramey, S. L. (1998). Early intervention and early experience. American Psychologist, 53(2), 109-120. [ Links ]

31. Shonkoff, J. P. & Meisels, S. J. (1990). Early childhood intervention: the evolution of a concept. In S. J. Meisels & J. P. Shonkoff, Handbook of Early Intervention (pp. 3-31). Camnbridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

32. Soriano, V. (2000). Intervención Temprana en Europa. Tendencias en 17 países europeos. Agenda Europea para el Desarrollo de la Educación Especial. Madrid: Real Patronato de Prevención y atención a Personas con Discapacidad. [ Links ]

33. Soriano, V. & Kyriazopoulou, M. (2010). Atención Temprana. Progresos y desarrollo 2005-2010. (pp. 1-66). Middelfart: Agencia Europea para el desarrollo de la Educación Especial. [ Links ]

34. Wilson, L. L. & Dunst, C. J. (2006). Checklist for assessing adherence to family-centered practices. CASE tools, 1(1), 1-6. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Francisco Alberto García-Sánchez.

Grupo de Investigación en Educación, Diversidad y Calidad.

Dpto. Métodos de Investigación y Diagnóstico en Educación.

Facultad de Educación.

Universidad de Murcia.

Campus de Espinardo. 30100, Murcia (Spain).

E-mail: fags@um.es

Article received: 16-07-2014

revised: 25-02-2015

accepted: 25-02-2015