Introduction

Stressful life events are a set of experiences that result in a significant change in people’s lives and have an enormous effect on their health (Compas, Orosan & Grantz, 1993). They are associated with a large number of negative consequences (Troy & Mauss, 2011) and have been significantly related to alcohol abuse and other substance abuse (Chaudhury, Goel & Singh, 2006; Jose, Oers, Mheen, Garretsen & Mackenbach, 2000; Lijffijt, Hu & Swann, 2014). In this regard, substance abuse may be a mechanism with which to alleviate symptoms related to trauma and mitigate memories associated with the past and the abuse suffered (Caldentey et al., 2017; Heim et al., 2000; Lloréns, Morales, De Vicente & Calatayud, 2002; Ramos, Saldívar, Medina, Rojas & Villatoro, 1998).

The stressful life events associated with substance use that have been addressed most thoroughly in the scientific literature are related to poverty, the existence of economic problems, unemployment, social problems, and/or a history of violence in their family of origin (Balk, Lynskey & Agrawal, 2009; Buzawa & Buzawa, 2014; Lemaitre, García-Jaramillo & Ramírez 2014). In particular, those who have suffered violence-related trauma in childhood, such as psychological, physical, and/or sexual abuse develop behaviors related to substance abuse (Afifi, Henriksen, Asmundson & Sareen, 2012). The factors that seem to predict worse outcomes for victims who suffered sexual abuse in childhood are the presence of stressful life events throughout their lives, the frequency and duration of the abuse, possible rape, and if the aggressor was a family member (Finkelhor, 1999). Moreover, the consequences of child sex abuse are uncertain, although substance use is among the main aftereffects in adult victims of child sex abuse (Echeburúa & Corral, 2006).

Several studies have also found that experiencing significant family transitions, such as grief, results in serious problems both in adults and young people, which may be related to substance use (Sandler, Tein, Cham, Wolchik & Ayers, 2016), as events related to the death of family members interrupt balance in personal relationships and affect psychological wellbeing (Melhem, Walker, Moritz & Brent, 2008). Additionally, the loss of family members is followed by other stressful life events that would increase trauma (Nolen-Hoeksema & Ahrens, 2002).

However, some authors have found that the increase in addiction to said substances is proportional to the number of stressful life events experienced, regardless of the type of event (Siqueira, Diab, Bodian & Rolnitzky, 2000). Even without presenting a psychological disorder, people who have suffered an average of three or more stressful life events have more behaviors related to drug and alcohol consumption (Balk et al., 2009; Dawson, Grant & Ruan, 2005) compared to those who have experienced a lesser number of such events.

According to Lijffijt et al. (2014), trauma suffered as an adult predicts substance dependence, as said trauma may be more chronic and more closely related to addiction. For other authors, trauma experienced in childhood has a greater implication on one’s future. In this regard, when stressful life events occur at early ages they result in serious consequences, given that they threaten psychological wellbeing in response to the adversity resulting from events such as exposure to violence, chronic disease in parents, the death of family members, suffering from physical and/or sexual violence in childhood, and situations related to contexts of poverty (Grant et al., 2003; Grant et al., 2006). Additionally, research has indicated that there is a relationship between these life events suffered in childhood and substance use, especially alcohol use (Cuijpers et al., 2011; Nelson et al., 2002; Young-Wolff, Kendler & Prescott, 2012). However, there are difficulties in comparing such events at different moments of development, as the cognitive assessment of these events may vary over time (Grant et al., 2003).

Alcohol consumption appears to be more common among victims of gender violence (GV) than in the rest of the female population (Devries et al., 2014). The prevalence of alcohol consumption among victims of GV has been estimated at around 18.5%, which is much higher than the rate among women in the general population (4%-8%) (Golding, 1999). Other studies indicate that between 25%-75% of women addicted to alcohol or other substances have suffered from more types of violence with greater severity (Caldentey et al., 2017; Feingold, Washburn, Tiberio & Capaldi, 2015). Several studies report a higher probability of substance abuse among young women victims of GV (Howard & Wang, 2003; Kreiter et al., 1999; Silverman, Raj, Mucci & Hathaway, 2001). However, not all studies have found a greater tendency towards the consumption of substances, even in cases where the women have intense psychological malaise as a result of the abuse to which they have been subjected (Rincón, Labrador, Arinero & Crespo, 2004). It has also been reported that victims who succeed in leaving their violent environment tend to reduce their consumption levels, even without professional help (Walker, 1984). However, alcohol consumption has been linked to the perpetration of violence (Redondo & Graña, 2015) rather than to victimisation (Breiding, Black & Ryan, 2008).

Therefore, the combination of gender violence (GV) and stressful life events poses a risk to victims’ health. According to Sullivan et al. (2016), when these circumstances concur, it may cause women to be prone to frequent drug and alcohol use. Additionally, the relationship between violence and substance use may present as a vicious cycle, as substance use may be a coping mechanism, and at the same time, substance use may be a risk factor for suffering abuse in a more repeated, and more serious fashion (Simonelli, Pasquali & De Palo, 2014). In this regard, professionals who work with victims of violence play a fundamental role in detection and treatment and must consider the repercussions of the combination of these circumstances (Caldentey et al., 2017). However, while studies have been carried out in recent decades that address the relationship between substance abuse and suffering from violence, these studies are lacking in developing countries, where circumstances of vulnerability are increased (Vázquez & Panadero, 2016). Additionally, research on the impact of violence on women has been conducted in high-income countries, and therefore it is unknown to what extent these findings describe countries with lower development indicators (Ellsberg & Emmelin, 2014).

According to the WHO (2017), 150 million girls in the world (17%) are forced to have sexual relations and are subjected to other types of sexual violence every year. In Latin America, where rates of child sexual victimisation range between 26% and 38% (Ulibarri, Ulloa & Camacho, 2009), the increase is even greater. It is difficult to determine the real incidence of this problem, since it usually occurs in the private sphere (Noguerol, 1997). In Nicaragua (ranked 125th in the Human Development Index, (United Nations Development Programme, 2015), one in three women has experienced physical or sexual violence at some point in their life (DÁngelo & Molina, 2010). Although there have been limited studies on the prevalence of child victimisation in the country (Larraín & Bascunan, 2008). According to data reported by the professionals at the Nicaraguan Commissariat for Women (CW), there were more than 6,400 reports of domestic violence between 2012 and 2014 in León, the country's second most important city after the capital. 1,715 of these involved violence against victims under 18 years of age (around 50% were under 13 years of age). Several authors also report a correlation between violence and high rates of poverty (Arriagada, 2005; Ellsberg, Peña, Herrera, Liljestrand & Winkvist, 1999).

The purpose of this study is to analyze the risk of substance abuse in victims of GV exposed to various stressful life events throughout their lives in a context of extreme poverty in León (Nicaragua), a reality that is in need of receiving greater visibility in the scientific literature. The hypothesis is that there will be a relationship between experiencing stressful life events and substance use (Balk et al., 2009; Caldentey et al., 2017; Sandler et al., 2016; Siqueira et al., 2000), and that these events will result in a greater risk for substance use when experienced at early ages. It should be noted that the use of violence in Nicaragua seems to be part of the values developed in family dynamics, such that violence against women and girls is widespread (Tinoco et al., 2015), and is a problem exacerbated by extreme poverty, which is transmitted through the generations (Vázquez & Panadero, 2016).

Method

Participants

The participants in the study were 136 women in situations of extreme poverty who were the victims of GV in León (Nicaragua). This is a group that is difficult to access, as they are subject to a particularly serious set of adverse conditions related to their situation of poverty and having suffered stressful life events throughout their lives (Vázquez, Panadero & Rivas, 2015). The criterion for inclusion in the sample was being a woman over 18 years of age, a victim of GV and being in a situation of poverty. The interviewees, whose mean age was 31.67 years old (SD = 8.92), had 2.23 children (SD = 1.65). More than half (56.7%) were married or in a stable union. The educational level of the participants was basic education (68.4%). The primary breadwinner in the household, which contained a mean of 4.48 people, was the spouse or partner, in 43% of cases. 36% of the participants had no income of their own. The interviewees began to live with their abuser at an average age of 19.91 years (SD = 4.92), had been living with him - or had lived - with him for a mean of 9.16 years (SD = 6.78), and the abuse lasted for 6.25 years (SD = 5.48). 42% were living with their abuser when the interview took place. Furthermore, all the interviewees were victims of psychological and physical violence, and 66.9% had suffered from sexual violence. The abuse by the partner occurred on a daily basis in one out of four cases, and the abuse occurred several times a week for 44.7% of the sample of participants.

Instruments

Information regarding age, number of children, marital status, education level, as well as information related to the main income contributor, etc. was collected. Data were also collected on the situation of violence, the amount of time they lived with their assailant, duration of the situation of abuse, type of abuse, and the frequency with which it occurred.

An abbreviated version of the List of Stressful Life Events for socially excluded groups (L-SLE) was used (Vázquez & Panadero, 2016), which was created based on a revision of Brugha and Cragg’s (1990) instrument and on prior work used in research with socially excluded groups and groups in contexts of poverty (Panadero, Vázquez & Martín, 2017; Roca, Panadero, Rodríguez-Moreno, Martín & Vázquez, 2019; Vázquez, Panadero & Rincón, 2010; Vázquez et al., 2015). It consists of 26 items (10 suffered before age 18 and 16 from that age on). The different items had yes or no responses with regard to whether the events had occurred. The age at which they occurred for the first time was also included. The items related to violence suffered before 18 years of age were considered (physical abuse, sexual abuse, and exposure to violence suffered by the interviewee’s mother, as well as background regarding their parents’ substance use), as were items related to violence suffered throughout their lives not related to their partner (physical and sexual violence perpetrated by people other than their partner, the death of close family members, and circumstances related to poverty, such as having or having had significant economic problems). The chosen variables (having consumed alcohol and/or drugs in excess) were part of the L-SLE. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha (α = .85) indicates an acceptable level of internal consistency.

Procedure

Access to the interviewees was facilitated thanks to the support provided by different associations and public institutions that work with women in situations of poverty in León, including the National Police of Nicaragua. The information was obtained through a structured interview that lasted between 45 and 80 minutes. The interviews began by explaining the research objectives and participants were asked for their informed consent. The women were interviewed in different locations: 51.6% in their homes, 38.9% in the offices of the Precinct for Women in León, and 9.5% at the offices of various associations.

Data Analysis

The cases and controls method was used, with a quantitative focus and ex post facto design, in which the independent variables were compared with regard to alcohol and/or drug use. The database was developed and processed with SPSS (version 25.0 for Windows, IBM, Arnobk, NY). Chi-squared and Student’s t were used with the probability of making a type I error of p < .05. Odds ratio (OR) analyses were applied with confidence intervals of 95% (CI). A binary logistic regression analysis was carried out in order to predict which variables were related to the excessive consumption of alcohol and drugs by the interviewees. The required sample size was also calculated for the main analyses using G*Power Software (version 3.0 for Windows). Aspiring for an effect size of .5 (large), significance of .005, and a power of .95, the sample size surpasses the necessary size (n = 80).

Results

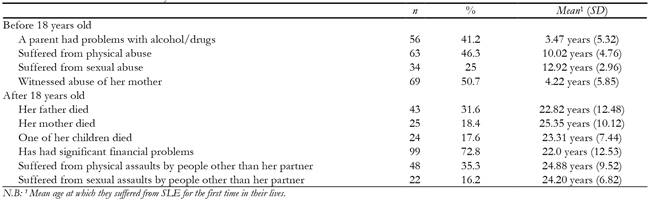

Table 1 shows the stressful life events suffered by the total of participants. With regard to the stressful life events suffered before age 18, it was found that there was a history of substance use in the family of origin in over 40% of the cases. Additionally, half of the sample suffered from physical abuse and was exposed to abuse from a very young age. This type of abuse also occurred after age 18, perpetrated by people other than their partner. In addition to these stressful life events, economic difficulties affected a high percentage of the sample.

Statistically significant differences were found with regard to alcohol use and the number of stressful life events suffered before age 18 (t = -3.046; p = .003). Those who used alcohol had suffered from a higher number of stressful life events (M = 2.03; SD = 1.581) than those who did not consume alcohol (M = 1.30; SD = 1.090). No differences were found between the two groups when these events occurred in adulthood (t = -1.606; p = .111). For drug use, statistically significant differences (t = -7.850; p = .000) were found with regard to the number of stressful life events suffered before age 18, where those who consumed drugs had suffered a higher number of these events (M = 3.42; SD = .851) than those who did not use drugs (M = 1.42; SD = 1.272). There are also differences with regard to the number of events experienced after age 18 (t = -2.719; p = .007) in terms of those who consumed drugs in excess (M = 2.78; SD = .892) and those who did not consume these substances (M = 1.81; SD = 1.292). Finally, there are statistically significant differences for alcohol use depending on the total number of stressful life events suffered before and after age 18 (t = -2.854; p = .004) between those who used alcohol (M = 4.14; SD = 2.434) and those who did not (M = 3.06; SD = 1.862). The differences are greater for excessive drug use (t = -5.235; p = .000), where those who consumed drugs (M = 6.21; SD = 1.423) had experienced a greater number of stressors than those who did not use drugs (M = 3.24; SD = 2.062).

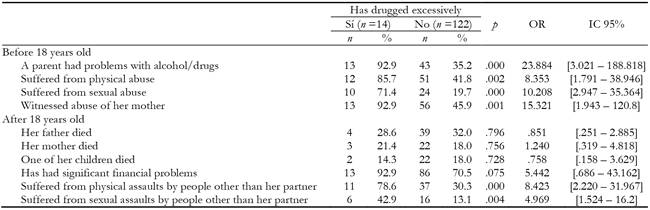

Table 2 shows the statistically significant differences with regard to drinking in excess according to experiences related to physical and sexual violence suffered before age 18. The odds ratio analyses show that the association with regard to alcohol use is large among those who had suffered physical and sexual abuse before age 18. Statistically significant differences were also observed with regard to the excessive consumption of alcohol in stressful life events experienced after age 18 with regard to experiencing abuse. Although the odds ratio analyses show that there is a high association between alcohol use and having suffered from physical and/or sexual abuse, the effect size is smaller when said abuse occurred in childhood. No relationship was observed between alcohol abuse and the parents having substance abuse issues, nor does there seem to be a relationship with the death of people in the family environment.

In order to determine which variables most exactly predict the excessive consumption of alcohol; a binary logistic regression analysis was carried out (Table 3). The predictor variables included in the analysis were the stressful life events suffered that were statistically significant and for which a strong association with alcohol abuse was found. The resulting model to predict alcohol use allows for a correct estimation of 55.1% of cases (( 2 = 22.99; p = .000). Furthermore, the Hosmer-Lemeshow test resulted in a significance of p = .962, showing an excellent goodness of fit for the model.

Therefore, sexual abuse before and after age 18 constitute two risk factors for alcohol abuse, even after incorporating physical abuse before and after that age into the model (Table 3).

As can be seen in Table 4, drug abuse is associated with more types of stressful life events. It is related to parents’ substance abuse and to suffering abuse before age 18. Drug abuse is also influenced by physical and sexual assault perpetrated by people other than their partner. The strength of the association between these events and drug abuse is high.

The predictive analysis for drug abuse included the stressful life events that were statistically significant (Table 5). The resulting model to predict drug abuse includes suffering from sexual abuse before age 18 and their parents having a history of substance abuse. The analysis allows for a correct estimation of 98.7% of cases (( 2 = 28.333; p = .000). Furthermore, the Hosmer-Lemeshow test resulted in a significance of p = .651, showing an acceptable goodness of fit for the model. The data show that suffering sexual abuse and parents’ substance abuse predicts drug abuse among participants.

Discussion and Conclusions

To begin, among the characteristics that describe the sample, the women interviewed suffered a set of especially serious stressful life events related to violence before and after age 18. Close to half of the interviewees were directly or indirectly exposed to different types of abuse at early ages. The numbers found in this study are higher than estimates given for the Latin American region (DÁngelo & Molina, 2010; Ulibarri et al., 2009), thereby providing data on the scope of this problem and adding information to the scant research done in developing countries (Ellsberg & Emmelin, 2014; Larraín & Bascunan, 2008; Vázquez & Panadero, 2016). Therefore, and along the same lines as indicated by Tinoco et al. (2015), in Nicaragua it seems that there is a normalization and tolerance of the use of violence in family dynamics.

Moreover, the prevalence of women who were the victims of GV who abused alcohol and drugs (45% and 10.3%, respectively) is higher than that found in prior studies performed in other contexts (Golding, 1999; Rincón et al., 2004; Walker, 1984). Some studies have found that this behavior is more common among assailants than victims (Breiding et al., 2008; Redondo & Graña, 2015), although prior research also indicates that substance abuse is more prevalent among women who have suffered from GV compared to the rest of the female population (Devries et al., 2014). However, it is significant that there is such a high percentage of substance abuse, given that substance use among women in Nicaragua is not very common (OPS, 2007).

Additionally, it seems that there is a relationship between the number of stressful life events suffered and substance use (Balk et al., 2009; Caldentey et al., 2017; Siqueira et al., 2000). Specifically, a greater number of these types of events experienced in childhood correlates to alcohol use, although there was no relationship found between the number of traumatic experiences suffered after age 18 and alcohol use. The number of stressful life events experienced before and after age 18 is related to drug use, such that the accumulation of adverse experiences, even at different periods of development, has serious implications for drug use (Afifi et al., 2012; Finkelhor, 1999). The total number of stressful life events experienced by those who abused alcohol was over four. In the case of drug use, the participants suffered an average of six stressful life events; therefore, there is a relationship between the number of stressful life events and substance use, although the numbers found here were much higher than those from prior studies (Balk et al., 2009; Dawson et al., 2005). Thus, the interviewees who had suffered a higher number of stressful life events consumed alcohol and drugs in excess. Furthermore, substance abuse is related to negative, adverse experiences throughout these women’s lives (Chaudhury et al., 2006; Heim et al., 2000; Jose et al., 2000; Ramos et al., 1998), which could be a response to the violence they have suffered and the convergence of other traumatic experiences throughout their lives (Caldentey et al., 2017; Lloréns et al., 2002).

The results seem to indicate that not all stressful life events had an influence on the interviewees’ excessive consumption of alcohol and drugs, and they provide relevant information with regard to what type of traumatic events may have a greater effect. In particular, physical and sexual assault seem to have had a greater impact on substance use, mainly when it occurs at an early age, as it had a greater effect then compared to when it occurs in adulthood (Cuijpers et al., 2011; Echeburúa & Corral, 2006; Finkelhor, 1999; Grant et al., 2003; Grant et al., 2006; Nelson et al., 2002; Young-Wolff et al., 2003). With regard to other types of events, although some studies have found that alcohol and drug use is related to the loss of people in the family environment (Melhem et al., 2008; Sandler et al., 2016), the death of a parent or child did not have an effect on substance use. Economic problems, which affected three out of every four women, were also not connected to substance abuse, unlike the findings of other studies, which have linked this circumstance to excessive consumption (Balk et al., 2009; Buzawa & Buzawa, 2014; Vázquez & Panadero, 2016). In this regard, the generalized situation of poverty in Nicaragua does not seem to be perceived as a stressor, although some studies have indicated that poverty and violence are closely related (Ellsberg et al., 1999; Roca et al., 2019). Lastly, the reproduction of substance abuse behaviors from parents is not related to alcohol use, although it does seem to have affected drug use.

Although this study contributes relevant information in terms of the factors associated with substance use in a developing country about which there are few prior studies, it also has several limitations. First, the type of substances used could be specified, as well as the time period during which the substance use occurred. Additionally, as this is a cross-sectional study, it is difficult to compare the impact of stressful life events experienced at different moments of development. In this regard, according to Grant et al. (2003), the assessment and interpretation of such events may have varied over time. It should also be noted that the conclusions cannot be generalized to other contexts, although from a psycho-social standpoint, substance use behaviors were studied in a sample that had suffered a great number of adverse experiences, and it was determined which of these experiences predicted alcohol and drug abuse. This study also generates future lines of research: a more clinical approach related to the victims’ psychological health could be added, as could factors that help protect against stressful life events, such as the mediating role of social support or factors related to the participants’ personality or capacity for resilience.

Overall, the results show that substance abuse, in addition to having a negative effect on healing processes under the especially adverse conditions these women have experienced, is mainly related to physical and sexual violence experienced in childhood. These findings contribute important information given the absence of studies in developing countries, where the impact of violence on the victims is unknown (Ellsberg & Emmelin, 2014). In this context, the issue is even more complex, as there are no support mechanisms that work with women and girls who have suffered different types of abuse, such that said substance abuse could result in victims’ declining psychological and physical health (Rincón et al., 2004). Additionally, substance use increases their vulnerability for suffering from further violence (Feingold et al., 2015), mainly when said substance use becomes a coping mechanism used to alleviate memories associated with especially adverse experiences (Caldentey et al., 2017; Heim et al., 2000; Lloréns et al., 2002; Ramos et al., 1998), making it difficult to embark upon recovery processes.

text in

text in