My SciELO

Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO  Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

Print version ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.96 n.2 Madrid Feb. 2004

| ORIGINAL PAPERS |

Infliximab induces clinical, endoscopic and histological responses

in refractory ulcerative colitis

F. Bermejo, A. López-Sanromán, J. Hinojosa1, L. Castro2, C. Jurado2 and A. B. Gómez-Belda1

Gastroenterology Department. Ramón y Cajal University Hospital. Madrid. 1Digestive Diseases Section. Hospital de

Sagunto. Sagunto, Valencia. 2Digestive System Department. Virgen Macarena University Hospital. Seville. Spain

ABSTRACT

Background: infliximab is a monoclonal antiTNF-α antibody that has repeatedly shown to be effective in the management of Crohn's disease. However, data are scarce about its efficacy in ulcerative colitis.

Aim: to describe the joint experience of three Spanish hospitals in the use of infliximab in patients with active refractory ulcerative colitis.

Patients and methods: we present seven cases of ulcerative colitis (6 with chronic active disease despite immunosuppressive therapy, and one with acute steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis) treated with infliximab 5 mg/kg of body weight. Clinical response was evaluated by means of the Clinical Activity Index at 2, 4 and 8 weeks after initial infusion. Biochemical (erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein), endoscopic, and histological changes were also assessed.

Results: mean age of patients was 45.8 ± 17 years (range 23-77); 4 were female. No adverse effects were recorded. Inflammatory activity diminished significantly in 6 of 7 patients (85.7%; CI 95%: 42-99%) both from a clinical (p = 0.01) and biochemical (p <0.05) point of view. Five out of six patients (83.3%; 36-99%) with corticosteroid-dependent disease could be successfully weaned off these drugs. Five patients were endoscopicly controlled both before and after therapy, and a positive endoscopic and histological response could be recorded in all of them.

Conclusion: infliximab may be an effective and safe therapy for some patients with ulcerative colitis refractory to other forms of therapy, although controlled studies are needed to assess its role in the general management of this disease.

Key words: Infliximab. Ulcerative colitis.

Bermejo F, López-Sanromán A, Hinojosa J, Castro L, Jurado C, Gómez-Belda AB. Infliximab induces clinical, endoscopic and histological responses in refractory ulcerative colitis. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2004; 96: 94-101.

Recibido: 06-05-03.

Aceptado: 03-09-03.

Correspondencia: Fernando Bermejo San José. C/ Ríos Rosas, 17-5º C. 28003 Madrid. Tel.: 9133992617. e-mail: fbermejos@medynet.com

INTRODUCTION

Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), a proinflammatory cytokine, plays a central role in the pathogenesis of chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), especially in initiating and maintaining a pathological level of inflammation (1). Infliximab is a chimeric monoclonal IgG1 antibody directed against TNF-α that blocks both its soluble and transmembrane fractions; in addition, it neutralizes TNF-α-synthesizing cells and induces apoptosis in activated T lymphocytes, which is down-regulated in patients with IBD (2). Infliximab has been shown to be efficacious and safe in the management of patients with both fistulous and luminal refractory Crohn's disease (3,4), where its use is widespread (5,6). Recent data suggest that it could also be of use in the management of ulcerative colitis (UC), although the number of studies and the amount of evaluated cases are still scant. Our aim was to describe the joint experience of three Spanish hospitals in the management of refractory UC with infliximab, and its effect on endoscopic and histological changes.

METHODS

Cases of patients with UC who were treated with infliximab in three Spanish hospitals were cross-sectionally analyzed. All had a definite diagnosis of UC according to widely accepted criteria (7,8). The following data were gathered: epidemiological characterization, time since UC diagnosis, extension of colonic involvement, concomitant therapies when infliximab was administered, previous treatments failing to induce clinical remission and, eventually, adverse effects following infliximab administration.

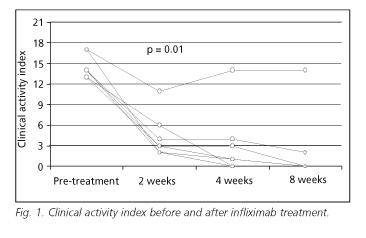

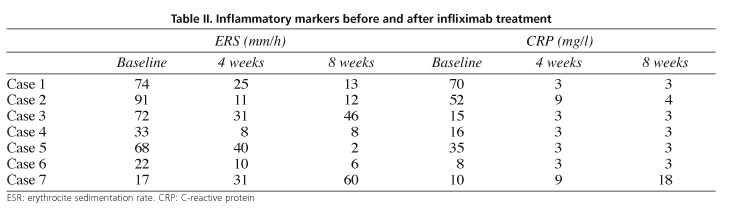

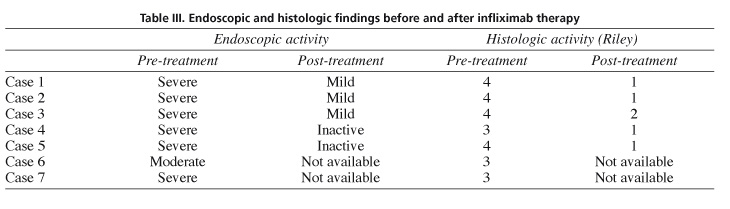

Disease activity was graded according to the Clinical Activity Index (CAI), by Lichtiger et al (9), with a highest possible score of 21. To evaluate the success of infliximab treatment (significant diminution of CAI), this index was calculated before infusion and at 2, 4 and 8 weeks thereafter; the success of steroid weaning was also investigated in steroid-dependent patients (defined as complete withdrawal of corticosteroids in oral or topical administration) (10). In all cases, complete blood count, liver enzymes, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and C-reactive protein were available before the infusion as well as 4 and 8 weeks thereafter. In all patients a colonoscopy with mucosal biopsies had been performed before infliximab therapy, and in 5 instances (all except numbers 6 and 7) a follow-up endoscopy with new biopsies was repeated at 6 to 8 weeks after infusion. To evaluate histological lesions, Riley's microscopic grading score was used (values from 0 to 4), a measure analyzing the degree of cellular inflammatory infiltrate and of tissue destruction present in the colonic mucosa (11).

Five of these patients were treated with a single IV infusion of infliximab, 5 mg/kg of body weight (Remicade®, Centocor, Malvern, PA, U.S.A.) strictly adhering to the manufacturer's instructions, and following the regular legal procedure for off-label administration established by the Spanish Ministry of Health. In one of the hospitals (patients 6 and 7) a three-dose schedule was chosen (0, 2 and 6 weeks), similar to what is widespread in the management of fistulous Crohn's disease refractory to immunosuppression (4,5).

The statistical study was carried out using the SPSS-10.0 pack. For qualitative variables, percentages and 95% confidence intervals (CI 95%) were calculated, and means and standard deviations were obtained for quantitative variables. A p value under 0.05 was considered statistically significant. An analysis of possible differences between pre- and post-treatment values was done by using Wilcoxon's test for paired data (signed rank test).

RESULTS

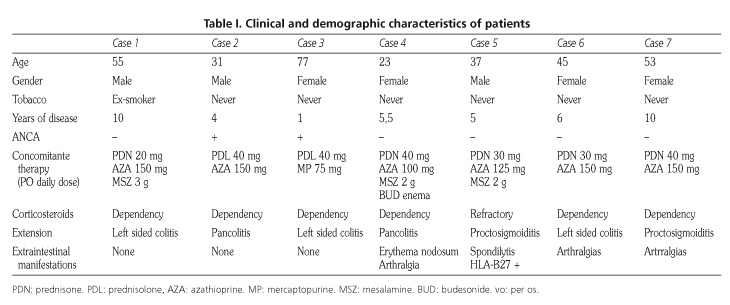

Seven patients were available for analysis: six cases of chronic active disease refractory to immunosuppressants and one case of acute severe colitis. In all of them baseline antinuclear antibodies were negative, as were the tests indicated to detect latent or active tuberculous infection (12). Prior to infusion, the diagnosis and the absence of cytomegalovirus superinfection were confirmed by endoscopy and biopsies in all cases. Mean age of patients was 45.8 ± 17 years (range 23-77); 4 were women. Clinical and demographic characteristics are defined in table I.

In case 1, cyclosporine had proved ineffective, and case 2 had unsuccessfully been treated with cyclosporine and tacrolimus. No adverse effects were detected during infliximab administration. During follow-up, one patient with a previous diagnosis of extrinsic asthma was admitted for mild, acute respiratory failure 8 weeks after infliximab infusion, and then discharged uneventfully.

Inflammatory activity significantly diminished (treatment success) in six out of seven patients (85.7%; CI 95%: 42-99%) both from a clinical and biochemical point of view. In figure 1, we depict the evolution of CAI, which significantly dropped two weeks after infusion (p = 0.01), a tendency kept for weeks 4 and 8. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein values also descended significantly (p < 0.05) at week 4 (Table II).

In five out of six patients with steroid-dependent disease, these drugs could be successfully withdrawn (83.3%; 36-99%). In cases 1 and 2 (6 months follow-up) and in case 3 (3 months follow-up), response was successfully maintained by infliximab infusions (5 mg/kg) every 8 weeks. Patients are treated with azathioprine and remain clinically asymptomatic (IAC: 0-2) and with normal values of C-reactive protein. In cases 4, 5 and 6, no maintenance infusions were administered, and all are still in clinical remission (6 months follow-up). The seventh patient still suffers from chronic active disease.

DISCUSSION

TNF-α is a key cytokine in the pathogenesis of IBD. It plays a leading role in inflammatory processes, with an important contribution to macrophage and neutrophil activation, increase of capillary permeability, extrinsic activation of coagulation pathways, and recruitment of various immunologic cells (13). Its role in the inhibition of T-lymphocyte apoptosis is also very striking. Classically, Crohn's disease and UC are described as corresponding to a Th1 (proinflammatory, TNF-α-mediated) and a Th2 (humoral) response, respectively (14). However, there is enough scientific evidence pointing at the important role played by TNF-α in UC (13), which supports the possible usefulness of anti-TNF-α therapy in this disease. Different authors have described active TNF-α synthesis both locally and systemically, as shown by an increased production in the colonic mucosa (15-17), and an increased detection in the stools, plasma, urine and rectal dyalisates of patients with active UC (18-20). Moreover, this increase correlates with disease severity as measured by clinical or laboratory parameters. A second line of evidence is supplied by the experimental treatment of animals with idiopathic UC using anti-TNF-α antibodies (CDP571). Such treatment is followed by weight gain and a partial reversal of histological mucosal changes (21).

Clinical situations where infliximab could be useful in UC include severe acute steroid-refractory disease, and chronic active disease refractory to immunosuppressants (azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine). In the first case, infliximab could be an alternative to cyclosporine, with the additional advantages of easier administration and no need to monitor blood levels (which makes the use of cyclosporine difficult in some settings). In such patients, data about infliximab efficacy are contradictory, with response rates varying between 33 and 100% (22-30). A recent placebo-controlled trial does not support the use of infliximab in this group of patients (29). Only one of our patients was treated for acute steroid-refractory colitis, with optimal results.

Another possible application is chronically active colitis that is refractory to immunosuppressive treatment, a situation where evidence is still more scarce and results very uneven, with response rates ranging from 0% (31) to 90% (25). In our series this indication was present in six patients, five of which showed a favourable response (83%) in accordance with observations by Su et al. (25). In our steroid-dependent patients those drugs were successfully withdrawn, as described by these authors (25).

The clinical response observed in a majority (85%) of our patients was supported by a significant descent in inflammatory markers. Endoscopic severity diminished significantly as well, and so did histological activity.

Finally, our results suggest that infliximab could be an alternative when other forms of treatment have failed. It is important to point out that, according to classical management, all our patients would have been candidates to colectomy, a procedure not free of morbidity and mortality (32). In spite of those promising results, it is important to be aware that the size of published series is small, severity of patients is not homogeneous, and doses and schedules vary. All this points to a need for multicenter, controlled, randomized studies to establish the true role infliximab may play for patients with UC mainly in two clinical situations: steroid-refractory disease, and chronic active colitis refractory to immunosuppressants.

REFERENCES

1. Hinojosa J. Anticuerpos anti-TNF en el tratamiento de la enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2000; 23: 250-7. [ Links ]

2. Sandborn WJ, Targan SR. Biologic therapy of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol 2002; 122: 1592-608. [ Links ]

3. Targan SR, Hanauer SB, van Deventer SJ, Mayer L, Present DH, Braakman T, et al. A short-term study of chimeric monoclonal antibody cA2 to tumor necrosis factor alpha for Crohn's disease. Crohn's Disease cA2 Study Group. N Engl J Med 1997; 337: 1029-35. [ Links ]

4. Present DH, Rutgeerts P, Targan SR, Hanauer SB, Mayer L, van Hogezand RA, et al. Infliximab for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med 1999; 340: 1398-405. [ Links ]

5. Domenech E, Esteve-Comas M, Gomollón F, Hinojosa J, Obrador A, Panés J, et al. Recomendaciones para el uso de infliximab (Remicade®) en la enfermedad de Crohn. GETECCU 2001. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2002; 25: 162-8. [ Links ]

6. Caprilli R, Viscido A, Guagnozzi D. Review article: biological agents in the treatment of Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2002; 16: 1579-90. [ Links ]

7. Lennard-Jones JE. Classification of inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol 1989; 170: S2-S6. [ Links ]

8. O'Morain C, Tobin A, Leen E, Suzuki Y, O'Riordan T. Criteria of case definition in Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol 1989; 170: S7-S11. [ Links ]

9. Lichtiger SC, Present DH, Kornbluth A, Gelernt I, Bauer J, Galler G, et al. Cyclosporin in severe ulcerative colitis refractory to steroid therapy. N Engl J Med 1994; 330: 1841-5. [ Links ]

10. Faubion WA, Loftus EV, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Sandborn WJ. The natural history of corticosteroid therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Gastroenterology 2001; 121: 255-60. [ Links ]

11. Riley SA, Mani V, Goodman MJ, Herd ME, Dutt S. Comparison of delayed release 5 aminosalicylic acid (mesalazine) and sulphasalazine in the treatment of mild to moderate ulcerative colitis relapse. Gut 1988; 29: 669-74. [ Links ]

12. Obrador A, López San Román A, Muñoz P, Fortun J, Gassull MA. Guía de consenso sobre tuberculosis y tratamiento de la enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal con infliximab. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2003; 26: 29-33. [ Links ]

13. Lichtenstein GR. Is Infliximab effective for induction of remission in patients with ulcerative colitis? Infl Bowel Dis 2001; 7: 89-93. [ Links ]

14. Fiocchi C. Inflammatory bowel disease: etiology and pathogenesis. Gastroenterology 1998; 115: 182-205. [ Links ]

15. Reinecker HC, Steffen M, Witthoeft T, Pflueger I, Schreiber S, MacDermott RP, et al. Enhanced secretion of tumour necrosis factor-alpha, IL-6, and IL-1 beta by isolated lamina propria mononuclear cells from patients with ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. Clin Exp Immunol 1993; 94: 174-81. [ Links ]

16. Masuda H, Iwai S, Tanaka T, Hayakawa S. Expression of IL-8, TNF-alpha and IFN-gamma m-RNA in ulcerative colitis, particularly in patients with inactive phase. J Clin Lab Immunol 1995; 46: 111-23. [ Links ]

17. Reimund JM, Wittersheim C, Dumont S, Muller CD, Baumann R, Poindron P, et al. Mucosal inflammatory cytokine production by intestinal biopsies in patients with ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. J Clin Immunol 1996; 16: 144-50. [ Links ]

18. Nielsen OH, Gionchetti P, Ainsworth M, Vainer B, Campieri M, Borregaard N, et al. Rectal dialysate and fecal concentrations of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin, interleukin-8, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol 1999; 94: 2923-8. [ Links ]

19. Saiki T, Mitsuyama K, Toyonaga A, Ishida H, Tanikawa K. Detection of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in stools of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol 1998; 33: 616-22. [ Links ]

20. Hadziselimovic F, Emmons LR, Gallati H. Soluble tumour necrosis factor receptors p55 and p75 in the urine monitor disease activity and the efficacy of treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 1995; 37: 260-3. [ Links ]

21. Evans RC, Clarke L, Heath P, Stephens S, Morris AI, Rhodes JM. Treatment of ulcerative colitis with an engineered anti-TNF alpha antibody CDP 571. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1997; 11: 1031-5. [ Links ]

22. Sands BE, Tremaine WJ, Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts PJ, Hanauer SB, Mayer L, et al. Infliximab in the treatment of severe steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis: A pilot study. Infl Bowel Dis 2001; 7: 83-8. [ Links ]

23. Chey WY, Hussain A, Ryan C, Potter GD, Shah A. Infliximab for refractory ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroentrol 2001; 96: 2373-81. [ Links ]

24. Kaser A, Mairinger T, Vogel W, Tilg H. Infliximab in severe steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis: A pilot study. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2001; 113: 930-3. [ Links ]

25. Su C, Salzberg BA, Lewis JD, Deren J, Kornbluth A, Katzka DA, et al. Efficacy of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in patients with ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2002; 97: 2576-84. [ Links ]

26. Kohn A, Prantera C, Pera A, Cosintino R, Sostegni R, Daperno M. Anti-tumour necrosis factor alpha (infliximab) in the treatment of severe ulcerative colitis: result of an open study on 13 patients. Dig Liver Dis 2002; 34: 626-30. [ Links ]

27. Actis GC, Bruno M, Pinna-Pintor M, Rossini FP, Rizzetto M. Infliximab for treatment of steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis. Dig Liver Dis 2002; 34: 631-4. [ Links ]

28. Castro Fernández M, García Díaz E, Romero M, Galán Jurado V, Rodríguez Alonso C. Tratamiento de la colitis ulcerosa corticorrefractaria con infliximab. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2003; 26: 54-5. [ Links ]

29. Probert CSJ, Hearing SD, Schreiber S, Kühbacher T, Ghosh S, Arnott IDR, et al. Infliximab in moderately severe glucocorticoid resistant ulcerative colitis: a randomised controlled trial. Gut 2003; 52: 998-1002. [ Links ]

30. Gornet JM, Couve S, Hassani Z, Delchier JC, Marteau P, Cosnes J, et al. Infliximab for refractory ulcerative colitis or indeterminate colitis: an open-label multicentre study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2003; 18: 175-81. [ Links ]

31. Kugathasan S, Prajapati DN, Kim JP, Saeian K, Emmons J, Knox J, et al. Infliximab outcome in children and adults with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2002; 122: A-615. [ Links ]

32. Binderow SR, Wexner SD. Current surgical therapy for mucosal ulcerative colitis. Dis Colon Rectum 1994; 37: 610-24. [ Links ]

text in

text in