My SciELO

Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

Print version ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.109 n.8 Madrid Aug. 2017

https://dx.doi.org/10.17235/reed.2017.5137/2017

Assessing medication adherence in inflammatory bowel diseases. A comparison between a self-administered scale and a pharmacy refill index

Valoración de la adhesión terapéutica en la enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal. Comparación entre una escala de autoevaluación y un índice farmacéutico de dispensación de medicamentos

María-Luisa de-Castro1, Luciano Sanromán1, Alicia Martín2, Montserrat Figueira1, Noemí Martínez2, Vicent Hernández1, Víctor del-Campo3, Juan-Ramón Pineda1, Jesús Martínez-Cadilla1, Santos Pereira1 and Ignacio Rodríguez-Prada1

Departments of 1Gastroenterology, 2Pharmacy, and 3Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine. Hospital Alvaro Cunqueiro. Complexo Hospitalario Universitario de Vigo. Instituto de Investigación Biomédica. Estrutura Organizativa de Xestión Integrada de Vigo. Vigo, Spain.

Institutional review board statement: The study was reviewed and approved by the Galician Clinical Research Ethics Committee, under resolution dated 4th June 2014 (registry code 2014/298). Patients' clinical histories were accessed for study purposes in accordance with the research protocols laid down by the clinical documentation department.

Grant support: This work was supported by a grant: 2015 Esteve Grant in Health Innovation.

ABSTRACT

Background: Medication non-adherence in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) has a negative impact on disease outcome. Different tools have been proposed to assess non-adherence. We aimed to compare a self-administered scale and a pharmacy refill index as a reliable measure of medication adherence and to determine what factors are related to adherence.

Methods: Consecutive non-active IBD outpatients were asked to fill in the self-reported Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS-8) and the Beliefs about Medication Questionnaire (BMQ). Pharmacy refill data were reviewed from the previous three or six months and the medication possession ratio (MPR) was calculated. Non-adherence was defined as MMAS-8 scores < 6 or MPR < 0.8.

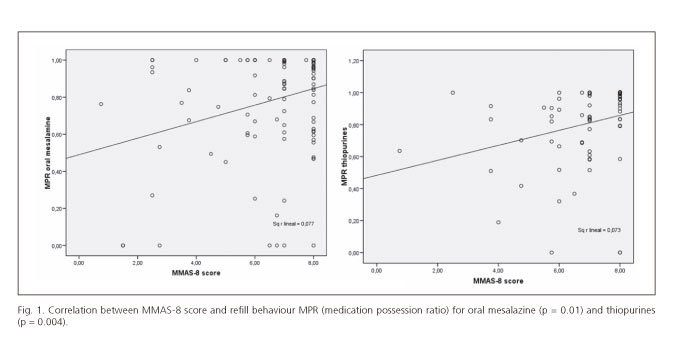

Results: Two-hundred and three patients were enrolled (60% ulcerative colitis, 40% Crohn's disease); 51% were men, and the mean age was 46.3 (14) years. Seventy-four per cent of patients were on monotherapy and 26% on combination therapy; altogether, 65% received mesalazine, 46% thiopurines and 16% anti-tumor necrosis factor alfa. Non-adherence rate assessed by MPR was 37% and 22.4% by MMAS-8. Receiver operator curve analysis using a MMAS-8 cut-off of six gave an area under the curve of 0.6 (95% CI 0.5-0.7), p = 0.001. This score had an 85% sensitivity and 34% specificity to predict medication non-adherence, with negative and positive predictive values of 57% and 70% respectively. High scores in the BMQ potential for harm of medication were significantly associated with MPR non-adherence (p = 0.01).

Conclusion: The accuracy of MMAS-8 to identify medication non-adherence in inactive IBD outpatients in our setting is poor due to a low specificity and a negative predictive value. Psychosocial factors such as beliefs about medication seem to be related to IBD non-adherence.

Key words: Inflammatory bowel disease. Medication adherence. Patient compliance. Surveys and questionnaires. Reproducibility of results. Pharmacy.

RESUMEN

Introducción: la falta de adhesión terapéutica en la enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal (EII) tiene un impacto negativo en el control de la enfermedad. Existen diferentes herramientas para evaluar la falta de adhesión. Nuestro objetivo fue comparar una escala de autoevaluación con un índice de posesión de medicación, e identificar los factores relacionados con falta de adhesión.

Métodos: solicitamos a pacientes ambulatorios con EII inactiva que rellenasen los cuestionarios de adhesión MMAS-8 y de opiniones sobre medicación BMQ. Revisamos los registros de dispensación farmacéutica en los 3-6 meses anteriores calculando el índice de posesión de medicación (MPR). Consideramos no adhesión terapéutica valores de MMAS-8 < 6 y MPR < 0,8, respectivamente.

Resultados: incluimos a 203 pacientes (60% colitis ulcerosa, 40% enfermedad de Crohn), 51% varones, edad 46,3 (14) años. Un 74% empleaba monoterapia y un 26%, terapia combinada; el 65% recibía mesalazina, el 46% tiopurinas y el 16% fármacos anti-TNF. La no adhesión fue 37% evaluada con MPR y 22,4% con MMAS-8. El área bajo la curva ROC del valor 6 de MMAS-8 fue 0,6 (IC 95%: 0,5-0,7, p = 0,001). Esta puntuación mostró una sensibilidad del 85% y una especificidad del 34% para predecir no adhesión terapéutica, con valores predictivos negativos y positivos del 57 y 70% respectivamente. Las puntuaciones altas en la subescala de daño del cuestionario BMQ se asociaron a no adhesión en MPR (p = 0,01).

Conclusión: la precisión de MMAS-8 para identificar falta de adhesión en pacientes con EII inactiva en nuestro entorno es pobre dada su baja especificidad y valor predictivo negativo. Las opiniones sobre la medicación parecen estar relacionadas con la adhesión terapéutica en EII.

Palabras clave: Enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal. Adhesión terapéutica. Cumplimiento del paciente. Encuestas y cuestionarios. Reproducibilidad de los resultados. Farmacia.

Introduction

Adherence to prescribed medication is a key factor for an effective disease management of many chronic conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Clinically non-active IBD patients are required to maintain medication adherence, as low adherence in IBD increases the risk of relapses and complications, the use of health services and healthcare costs (1,2).

Non-adherence rates in IBD range from 7 to 72%, with most studies reporting non-adherence rates of 30-40% (3). These large differences in adherence rates can be explained by differences in patient characteristics or in the methods used to measure adherence, as there is no single metric to investigate this and none are considered as the gold standard. Adherence can be measured via different methods such as validated self-administered surveys, metabolite measurements, pill counts or prescription claims, and the degree of agreement among these assessment methods can vary (4).

The eight-item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS-8) is a screening tool recently developed from the original 4-question Morisky survey (5), as this scale was considered as accusatory and often evoked defensiveness from patients. It has been shown to be reliable for non-adherence with a good sensitivity and specificity and correlated well with patient adherence as measured by pharmacy refills in some diseases (6,7). However, there is conflicting data for patients with IBD. The few published studies have shown a fairly good correlation between MMAS-8 and pharmacy fill rates (8,9) but it appears to be limited for a specific drug class (9,10).

Among the diverse factors related to non-adherence, a patient's beliefs about medication have been recently highlighted (3,11). The Beliefs about Medication Questionnaire (BMQ) is a standardized scale assessing specific concerns about medication that a person is taking and general beliefs about the importance of medication (12,13).

The aim of this study was to assess therapeutic adherence in clinically non-active IBD patients comparing the MMAS-8 scale with a pharmacy refill rate (the medication possession ratio [MPR]) as reliable methods to measure medication adherence and to determine which factors are related to adherence in this population.

Materials and methods

Study population and data collection

All consecutive patients with Crohn's disease (CD) or ulcerative colitis (UC) attending the IBD outpatient clinic of the Department of Gastroenterology at the Xerencia de Xestion Integrada de Vigo (Vigo, Spain) from November 2014 to April of 2015 were invited to participate in this study.

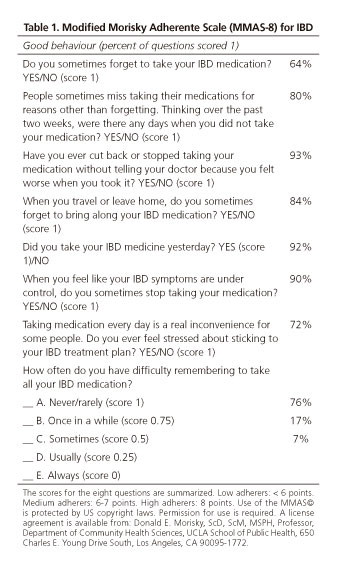

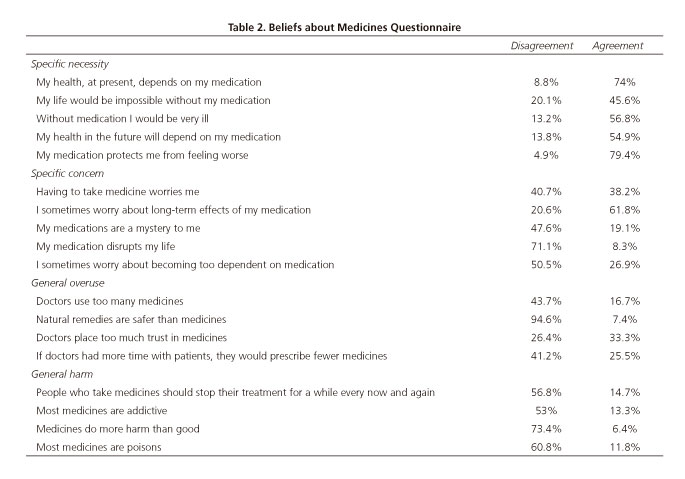

Patients were included if they consented to participate and were under treatment with any of the following drugs: topical or oral mesalazine, immunomodulators (thiopurines or methotrexate) and anti-tumour necrosis factor alfa (anti-TNFα). Exclusion criteria for the study were: age under 18 years, clinically active IBD defined as a modified Mayo score ≥ 2 in UC or a Harvey-Bradshaw index ≥ 5 in CD, changes of treatment in the three months prior to the visit or patients unable to understand or fill out the questionnaires correctly. Trained IBD nurses collected demographic and social data (age, sex, employment, level of education), habits (tobacco, alcohol, drugs), use of alternative therapies for IBD and concomitant medication. They assessed clinical activity on the day of enrollment by calculating the Mayo or the Harvey-Bradshaw scores as appropriate, and the patients were asked to answer the MMAS-8 (Table 1) and the BMQ (Table 2) questionnaires (official Spanish versions) anonymously. These were kept separately from any clinical information in a closed box. In a nearby room, an IBD physician filled-in additional IBD related data such as disease location and extent, time from diagnosis, prescribed treatment, hospitalizations or surgery requirements during the previous six months.

The MMAS-8 and BMQ surveys

The MMAS-8 is an eight-question self-reported survey and each item measures a specific medication-taking behavior (Table 1). Response categories are YES/NO for each item (i.e., a dichotomous response) and a five-point Likert response for the last item. In previous reports, a score of less than six points was interpreted as low adherence, six/seven as medium adherence and eight points as high adherence (7). As in other studies, we grouped together medium and high adherers and labelled them as MMAS-8 good adherers as there is neither a clear definition of medium and high adherence in the literature nor a clear clinical discrimination between the scores six to eight. Permission for the use of the MMAS-8 was granted by Dr. Donald Morisky, the copyright holder of the scale.

The Beliefs about Medication Questionnaire (BMQ) is an 18-item standardized scale assessing specific concerns about medication that a person is taking and the general beliefs about the importance of that medication (5-items each) (Table 2). It also measures beliefs about the potential for harm and overuse of medication in general (4-items each). Individual scale items are scored using a five-point Likert-type scale and computed by adding individual item scores to provide a total score in each category (13).

Medication adherence by pharmacy refill index

Medication adherence prior to study enrollment was calculated for all IBD drugs during the previous three months except for anti-TNFα drugs. In this case, adherence was calculated for the previous six month due to its dosage. Information on dispensed medication was obtained from the pharmacy databases and hospital pharmacy electronic records when the medication was dispensed by the hospital (anti-TNFα drugs). The evaluation of adherence was assessed by the mean medication possession ratio (MPR), which is defined as the proportion or percentage of days supply of drugs obtained during the specified time period or over a period of refill intervals. Patients were considered as adherent if the MPR was at least 80% (value ≥ 0.8) (14). This dichotomous cut-off is somewhat arbitrary, however, it has been used for the majority of the studies in the medication adherence literature with data from both observational and randomized controlled clinical trials. MPR values were computed separately for each drug of every individual patient, although patients on IBD combination therapy were considered to be adherent only if they reached a MPR of ≥ 0.8 in every drug they were expected to take.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS software (version 15.0, San Diego, CA USA). All analyses were two-tailed and p values under 0.05 were considered as significant. Quantitative variables were expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed data and as median and interquartile range for non-normally distributed data. Categorical variables were expressed as a total number and frequencies (%). Quantitative variables were analyzed using the Student's t-test or Mann Whitney test and qualitative variables using the Chi-squared test. For stepwise forward multivariate binary logistic regression analysis, only candidate variables with p values ≤ 0.05 on univariate analysis were included. Receiver operator curve analysis was used to determine the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV) and overall accuracy of MMAS-8 to detect MPR non-adherence.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Galician Clinical Research Ethics Committee, under resolution dated 4th June 2014 (registry code 2014/298). Patients' clinical histories were accessed for study purposes in accordance with the research protocols laid down by the clinical documentation department.

Results

Overall characteristics of patients

Three hundred and forty-two IBD patients attended our IBD outpatient clinic in 54 scheduled appointments during the study period. One hundred and fourteen patients had clinically active IBD or had recently changed treatment, 15 showed difficulties with reading or understanding the questionnaires and ten did not sign the informed consent. Altogether, 203 consecutive patients were recruited to the study. One hundred twenty-one patients (60%) had ulcerative colitis, 82 (40%) had Crohn's disease and 103 patients (51%) were men. The mean age was 46.3 (13.7) years and the mean duration of the disease was 10.3 (7.6) years. One hundred and forty-nine IBD patients were on monotherapy (73.8%) and 52 (26.2%) were receiving combination therapy with two or more drugs. Of these, 131 patients (65%) were on mesalazine, 94 (46.5%) on thiopurines and 32 (15.8%) on anti-TNFα drugs. Seven patients did not fill out the MMAS-8 survey properly, and MPR could not be calculated in two other cases, hence a total of 194 patients were compared with MMAS-8 and MPR data.

Medication non-adherence measured by MMAS-8

According to the MMAS-8 survey, 36% of patients admitted that they sometimes forgot to take their IBD medication and 20% admitted to non-adherence in the two weeks before their medical appointment. Ten per cent said they stopped taking medication when they felt well and 7% did the same because they felt worse when they took the medication (Table 1). The mean MMAS-8 score was 6.7 (1.6), 44 patients (22.4%) had a score < 6 and were classified as low adherers, 73 (37.2%) scored > 6 to 8 and were considered as medium adherers, and 79 (40.3%) were high adherers as they scored 8. Among the MMAS-8 low adherent patients, 57% had non-persistent medication fill rates (MPR < 0.8), whereas this value was 38.4% in medium and 27.8% in high adherers. The differences among the three groups were statistically significant (p = 0.007).

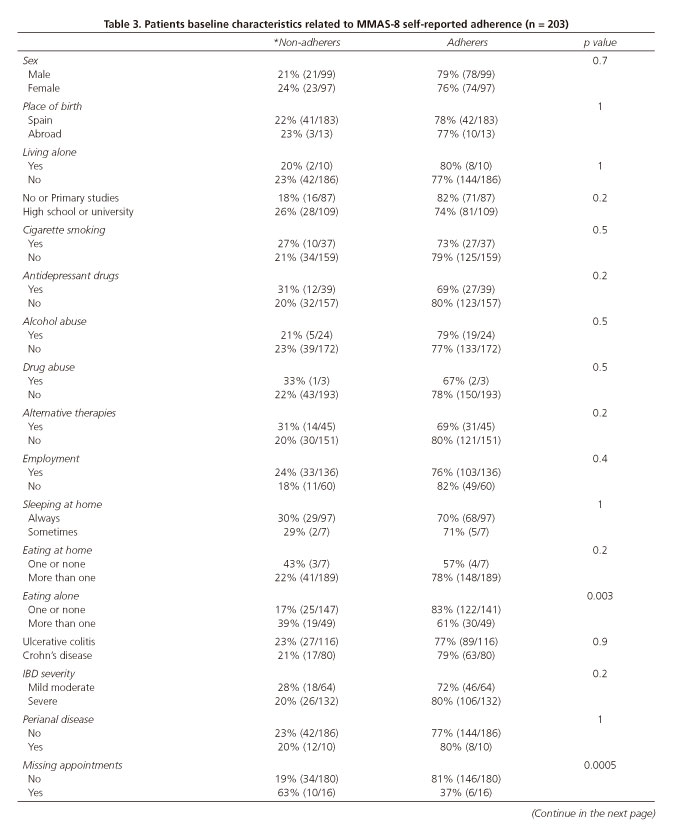

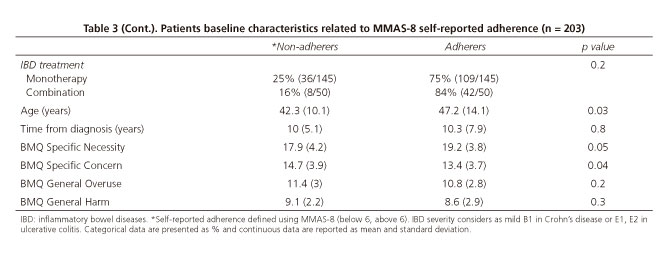

Patients with MMAS-8 scores < 6 were labelled as MMAS-8 non-adherers. The clinical characteristics of these patients are shown in table 3.

BMQ answers (Table 2) revealed that 38.2% of IBD patients were worried about taking medicines and 61.8% were worried about long-term potential adverse effects of the medication. Nevertheless, they did not have doubts about their personal need for IBD medication (45.6%-79.4%). Participants were prone to disagree with statements suggesting that all medication is harmful (60.8%) or addictive (53%) and they tended to deny statements such as "doctors usually overuse medication" (43.7%).

Univariate analysis showed that young age, eating alone, missing scheduled medical appointments and high levels of concern about IBD medication in BMQ were significantly associated with MMAS-8 non-adherence (p < 0.05) (Table 3). Multivariate logistic binary regression analysis (OR, 95% CI, p value) confirmed that eating alone more than once per day (OR 3.3 [1.5-7.2], p = 0.002), missing scheduled medical appointments (OR 13.9 [3.7-52.5], p = 0.0001) and a lower perception of necessity for IBD medication (OR 1.1 [1-1.2], p = 0.01) were associated with self-reported MMAS-8 medication non-adherence.

Medication non-adherence measured by MPR

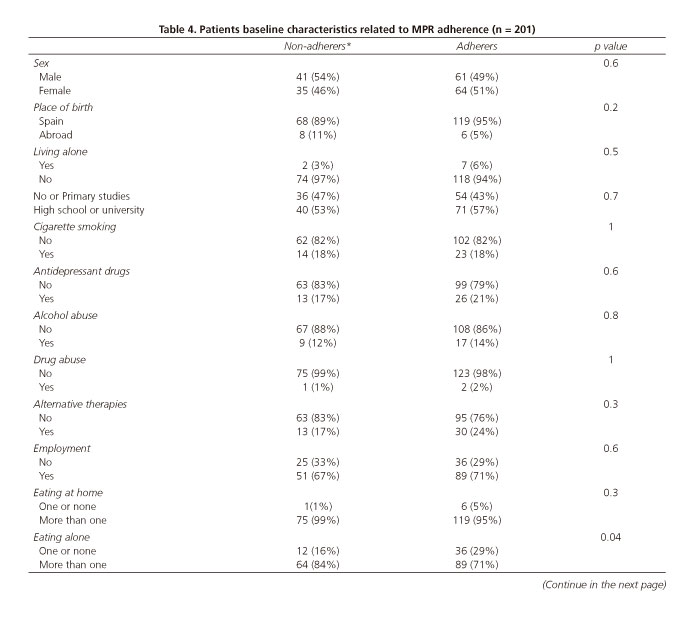

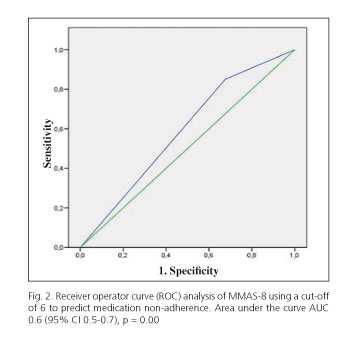

When assessing adherence by a MPR score ≥ 0.8, we classified 74 patients as non-adherers (37%). The clinical characteristics of these patients are shown in table 4.

The MMAS-8 score of MPR adherers was significantly higher than MPR non-adherers, 7 (1.4) versus 6.2 (2.2) (p = 0.001). Univariate analysis showed that only a higher score on the BMQ potential for harm of medication in general (p = 0.01) was significantly associated with MPR non-adherence (p = 0.004) (Table 4).

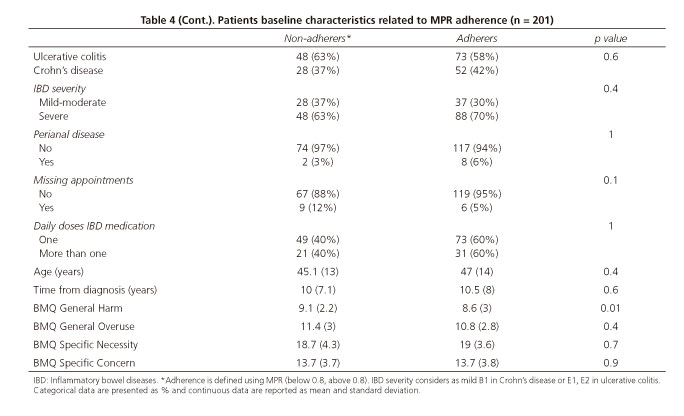

Regarding drug class, anti-TNF-α had the highest MPR adherence percentage (97%), which was statistically significant (p = 0.001), whereas thiopurines (66.3%), oral mesalazine (63%) and topical mesalazine (66.5%) had lower values. When combination therapy was evaluated, only 59% of patients on oral plus topical mesalazine, 60% on mesalazine plus thiopurines and 38% on anti-TNF-α plus thiopurines were considered as MPR adherers. The values of MPR percentage and MMAS-8 scores were significantly correlated for thiopurines (p = 0.004) and oral mesalazine (p = 0.01), although the data was very variable, even with higher MMAS-8 scores (Fig. 1).

Receiver operator curve (ROC) analysis of MMAS-8 scores using a cut-off value of six to predict MPR non-adherence gave an area under the curve of 0.6 (95% CI 0.5-0.7), p = 0.001. This cut-off value had a sensitivity of 85.5% and a specificity of 34% to detect MPR non-adherence, and the negative predictive value was 57% and the positive predictive value was 70% (Fig. 2).

ROC analysis using different MMAS-8 cut-off values from five to seven did not give a higher area under the curve, with values from 0.52 to 0.6 (data not shown).

Discussion

Even though therapy compliance is mainstay in IBD patients, only a minority of physicians check medication adherence on a regular basis (15) and the lack of validated screening tools may be the reason. Measuring metabolite levels in blood or urine is costly and has a high intra-patient variability. Pharmacy refills are time consuming and the clinician assessment seems unreliable (8,16). Self-reported adherence scales are accessible, inexpensive and easy to obtain while waiting to see the physician, although some reports have demonstrated that they tend to overestimate adherence when compared to objective monitoring methods (17).

In this study, the self-reported survey MMAS-8 identified 22% of patients as medication non-adherers, whereas pharmacy refill databases showed that 37% IBD patients had a MPR < 0.8. Therefore in our non-active IBD population, 15% of non-adherers were incorrectly identified as good adherers by MMAS-8.

However, MMAS-8 correlates with refill behavior, as good pharmacy refill adherers have higher MMAS-8 scores and MPR values are higher when the MMAS-8 score increases. However, its accuracy as a clinical screening tool to identify non-adherence behavior in non-active IBD patients is limited due to its low specificity (34%) and negative predictive value (57%). One explanation could be the fact that many patients tend to overestimate their adherence when questioned about it, thus decreasing the specificity and increasing the false positive results of this test.

When evaluating medication adherence among new therapy users, chronic users or mixed populations, we would expected to find different estimates of adherence, even if the same definitions and methods are employed for evaluation (14). Moreover, in non-active IBD patients, medication adherence declines over time and is harder to maintain than in active disease (4,18). These factors may explain why previous studies comparing MMAS-8 and MPR in IBD patients have shown contradictory data.

Trindade et al. found a very good accuracy of MMAS-8 to detect adherence behavior in IBD patients (8). They included both inpatients and outpatients only on monotherapy with varying degrees of disease severity. In contrast, this study enrolled clinically non-active IBD patients on both monotherapy and combination therapy, and deliberately excluded inpatients and patients recently diagnosed or that had active IBD, as this population is more likely to adhere to the medication. In this real life situation we found that MMAS-8 failed to detect 15% of non-adherent patients.

On the other hand, Kane et al. concluded that MMAS-8 might be helpful for the short term for certain classes of therapy, but not globally and not for long-term prediction of adherence in IBD patients, as only patients on thiopurines had a survey score that positively correlated with refill behavior in MPR (9). Similarly to Kane et al., we found a better relationship between MMAS-8 and MPR in relation to drug class as both methods showed a statistically significantly correlation in non-active IBD patients on thiopurines or mesalazine. However, the variability in the data and the fact that the data points in the graph do not closely cluster around the line of origin means that these results are not reliable even within a drug class.

Recently, Goodhand et al. reported that MMAS-8 reliably predicted thiopurine non-adherence compared to blood metabolite levels (10). Immunomodulator therapy has been previously associated to a better adherence (19,20), but the reasons are not clearly understood. Patients on immunomodulators usually suffer from a more severe disease, which is associated with a better adherence, and these patients are recommended to follow a strict medical control which could exert a positive effect on adherence.

Regarding drug class, patients on biological anti-TNF drugs showed a significantly high adherence with regard to other medication. This is likely due to the fact that these cases often suffer from a more complicated disease and many of these therapies are administered under controlled conditions in an outpatient clinic. However, an interesting observation in our study was that closely monitored patients on combination therapy with anti-TNF plus thiopurines showed a high rate of non-adherence with regard to thiopurine therapy. This could be due to patients' views about its potential toxicity and their ignorance to the additional benefits of thiopurines on their disease. In light of these results, we can consider these patients as a risk group for medication non-adherence.

Demographic characteristics and treatment variables have not been previously associated to non-adherence behavior (3). We found that IBD patients missing clinical appointments or eating alone frequently were prone to self-report MMAS-8 non-adherence. Although none of these characteristics were associated with MPR non-adherence. With regard to oral IBD medication, we did not find any relationship between the number of daily doses and adherence.

Moreover, patient attitudes and negative views about medication play an important role in voluntary non-adherence in chronic diseases (21), and a low perceived personal need for treatment and a high concern about potential adverse effects of treatment were associated to non-adherence in IBD patients (22). In this study, self-reported MMAS-8 non-adherence was associated with high levels of concern about IBD medication in BMQ, whereas high scores in potential for harm of medication in general were significantly associated with MPR non-adherence. Understanding the reasons given by patients for non-adherence could help to develop suitable programs to optimize treatment adherence, in which it will be necessary to introduce other important factors like the improvement of patients' knowledge of their disease (23,24).

With regard to the weaknesses of this study, MPR is a pharmacy refill index that measures medication availability but not consumption. However, this index is considered to have a high specificity for the identification of patients that do not consume their medication if patients are unlikely to obtain their medication from other sources that are not captured by the automated pharmacy databases (14), as is the case in our IBD patient cohort. Moreover, 22 non-active IBD patients did not fill out the MMAS-8 and BMQ questionnaires correctly, mainly due to the difficulties in understanding some of the language. Although we do not consider this as a bias, this fact should be taken into account in the development of future research tools to study adherence.

The main strength of the present study is that medication adherence in IBD patients has been assessed under real-life conditions. We have enrolled a homogeneous outpatient population with a non-active disease having to maintain chronic medication, mainly with multiple drugs.

Identification of non-adherers is the main goal in non-active IBD patients in order to identify different aspects that could improve adherence. We consider that a suitable screening tool to detect non-adherence must have a high specificity and negative predictive values, and not to be limited to the medication being taken. Our results indicate that MMAS-8 has a low accuracy to identify medication adherence in non-active IBD outpatients in our setting, due to its low specificity and negative predictive value. Thus, the search for an appropriate clinical tool continues. On the other hand, as demographic, clinical and treatment variables have not been consistently associated with non-adherence, we must focus on psychological and psychosocial factors such as beliefs about medication in future studies.

References

1. Kane S, Hou D, Aikens J, et al. Medication nonadherence and the outcomes of patients with quiescent ulcerative colitis. Am J Med 2003;114:39-43. DOI: 10.1016/S0002-9343(02)01383-9. [ Links ]

2. Kane S, Shaya F. Medication non-adherence is associated with increased medical health care costs. Dig Dis Sci 2008:53:1020-4. DOI: 10.1007/s10620-007-9968-0. [ Links ]

3. Jackson CA, Clatworthy J, Robinson A, et al. Factors associated with non-adherence to oral medication for inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol 2010;105:525-39. DOI: 10.1038/ajg.2009.685. [ Links ]

4. Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med 2005;353:487-97. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMra050100. [ Links ]

5. Morisky DE, Green LW, Levine DM. Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Med Care 1986;24:67-74. DOI: 10.1097/00005650-198601000-00007. [ Links ]

6. Krousel-Wood MA, Islam T, Webber LS, et al. New medication adherence scale versus pharmacy fill rates in seniors with hypertension. Am J Manag Care 2009;15(1):59-66. [ Links ]

7. Morisky DE, Ang A, Krousel-Wood M, et al. Predictive validity of a medication adherence measure in an outpatient setting. J Clin Hypertens 2008;10:348-54. DOI: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.07572.x. [ Links ]

8. Trindade AJ, Ehrlich A, Kornbluth A, et al. Are your patients taking their medicine? Validation of a new adherence scale in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and comparison with physician perception of adherence. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2010;17(2):599-604. DOI: 10.1002/ibd.21310. [ Links ]

9. Kane S, Becker B, Harmsen WS, et al. Use of a screening tool to determine nonadherent behavior in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:154-60. DOI: 10.1038/ajg.2011.317. [ Links ]

10. Goodhand JR, Kamperidis N, Sirvan B, et al. Factors associated with thiopurine non-adherence in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013;38:1097-108. DOI: 10.1111/apt.12476. [ Links ]

11. Horne R, Parham R, Res M, et al. Patients' attitudes to medicines and adherence to maintenance treatment in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2009;15:937-844. [ Links ]

12. Horne R, Weinman J, Hankins M. The Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire: the development and evaluation of a new method for assessing the cognitive representation of medication. Phychol and Health 1999;1-24. DOI: 10.1080/08870449908407311. [ Links ]

13. Beléndez-Vázquez M, Hernández-Mijares A, Horne R, et al. Evaluación de las creencias sobre el tratamiento: validez y fiabilidad de la versión española del "Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire". Int J Clin Heal Psychol 200;7:767-79. [ Links ]

14. Andrade SE, Kahler KH, Frech F, et al. Methods for evaluation of medication adherence and persistence using automated databases. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Safety 2006;15:565-74. DOI: 10.1002/pds.1230. [ Links ]

15. Trindade AJ, Morisky DE, Ehrlich AC, et al. Current practice and perception of screening for medication adherence in inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Gastroenterol 2011;45:878-82. DOI: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3182192207. [ Links ]

16. Wright S, Sanders DS, Lobo AJ, et al. Clinical significance of azathioprine active metabolite concentrations in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 2004;53:1123-8. DOI: 10.1136/gut.2003.032896. [ Links ]

17. Shi L, Liu J, Koleva Y, et al. Concordance of adherence measurement using self-reported adherence questionnaires and medication monitoring devices. Pharmacoeconomics 2010;28:1097-107. DOI: 10.2165/11537400-000000000-00000. [ Links ]

18. López-Sanromán A, Bermejo F. Review article: How to control and improve adherence to therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2006;24(S3):45-9. [ Links ]

19. Jason P, Ediger D, Walker JR, et al. Predictors of medication adherence in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2007;102:1417-26. DOI: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01212.x. [ Links ]

20. Bermejo F, López-San Román A, Algaba A, et al. Factors that modify therapy adherence in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohn Colitis 2010;4:422-6. DOI: 10.1016/j.crohns.2010.01.005. [ Links ]

21. Khanderia U, Townsend KA, Erickson SR, et al. Medication adherence following coronary artery bypass graft surgery: Assessment of beliefs and attitudes. Ann Pharmacother 2008;42:192-9. DOI: 10.1345/aph.1K497. [ Links ]

22. Moshkovska T, Stone MA, Clatworthy J, et al. An investigation of medication adherence to 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy in patients with ulcerative colitis, using self-report and urinary drug excretion measurements. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009;30:1118-27. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04152.x. [ Links ]

23. Argüelles-Arias F, Carpio D, Calvet X, et al. Conocimiento de la enfermedad y acceso al especialista descrito por pacientes españoles con colitis ulcerosa. Encuesta UC-LIFE. Rev Esp Enferm Digest 2017;109(6):421-9. [ Links ]

24. Robinson A. Review article: Improving adherence to medication in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008;27(Suppl 1):9-14. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03604.x. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

María-Luisa de-Castro.

Department of Gastroenterology.

Hospital Álvaro Cunqueiro.

Estrada Clara Campoamor, 341.

36212 Vigo, Spain

e-mail: maria.luisa.decastro.parga@sergas.es

Received: 23-02-2017

Accepted: 06-06-2017

text in

text in