My SciELO

Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

Print version ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.110 n.6 Madrid Jun. 2018

https://dx.doi.org/10.17235/reed.2018.4503/2016

SPECIAL ARTICLE

Spanish Consensus Document on Bariatric Endoscopy. Part 1. General considerations

1Hospital Universitario Quirón Dexeus. Barcelona. Spain

2Hospital Universitario Madrid Sanchinarro. Madrid. Spain

3Clínica Diagonal. Barcelona. Spain

4Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra. Pamplona. Spain

5Hospital Quirón Teknon. Barcelona. Spain

INTRODUCTION

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines overweight and obesity as an abnormal or excessive fat accumulation that presents a risk to health, in association with considerable morbidity and mortality 1. It currently represents the main health problem in developed countries 2, and has been dubbed the great epidemics of the 21st century. The European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO) reported in 2005 that in countries such as Spain 30% of the child population (7-11 years of age) was obese, with a prevalence of overweight and obesity above 39% and 15%, respectively, among the adult population (25-60 years of age) 3. According to this trend, the prevalence of overweight is expected to rise up to > 70% of the population, and that of obesity to > 40%, by 2020 4. Furthermore, the cost of expenses derived from this condition nearly surpass 10% of the total health care budget in the European Union 5.

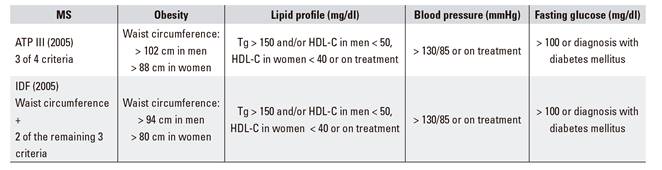

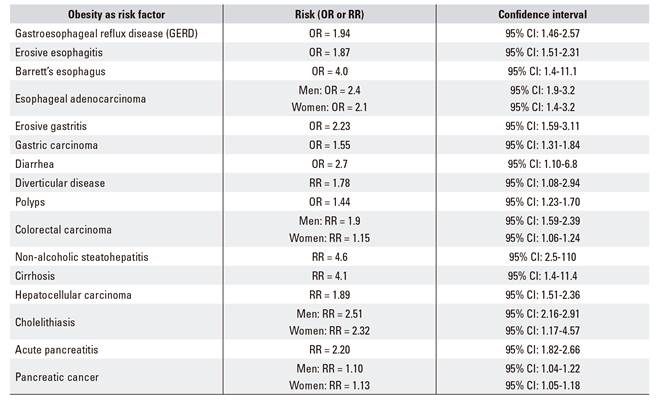

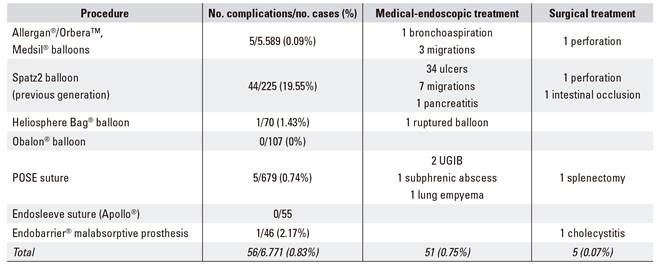

Obesity is a risk factor for multiple chronic diseases, including metabolic syndrome (type-2 diabetes mellitus, blood hypertension, dyslipemia) and its associated cardiovascular threats (Table 1A and Table 1B). Other digestive diseases (Table 1C), respiratory disorders, joint conditions, social stigma, etc., and even its association with some cancers (esophagus, colon, pancreas, prostate, breast), condition a significant decrease in quality of life and life expectancy as compared to non-obese patients, this being the primary preventable cause of mortality after tobacco smoking 6.

Table 1A Major and minor comorbidities associated with obesity, according to the SECO

OSAS: obstructive sleep apnea syndrome; OHS: obesity-hypoventilation syndrome.

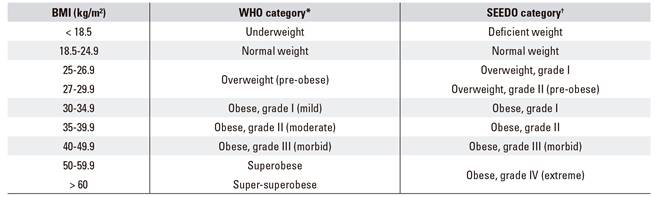

While obesity extent may be expressed in several ways, the most simple and practical approach during adulthood consists of calculating the body mass index (BMI, expressed as kg/m2) 7, which allows to establish an objective quantitative relationship (Table 2). Thus, the WHO and scientific societies alike consider there is overweight when the BMI is at or higher than 25 kg/m², and obesity when it is at or higher than 30 kg/m².

Table 2 Obesity grades

*Obesity grade according to the WHO. †Obesity grade according to the Sociedad Española para Estudio de la Obesidad (SEEDO) criteria.

Several therapeutic strategies exist according to obesity extent 8,9. Adequate dietary re-education, lifestyle modification, and physical exercise are key for all patients. This may be supplemented with drug therapy and/or specialist psychological support whenever necessary or indicated. Bariatric surgery remains the most effective long-term therapeutic alternative for patients with severe obesity (grade II) and associated metabolic conditions, and for patients with morbid obesity and superobesity (grade III-IV). However, despite its effectiveness, it has been estimated that less than 1-2% of obese patients potentially eligible for bariatric surgery eventually undergo these procedures as of today 10: high cost, associated morbidity (15-20% of major complications), potential mortality (strongly reduced over the past few years), and some persistent social "fear" might be some of the causes involved 11.

According to the Fobi-Baltasar criteria 12,13,14, which define quality indicators for the surgical treatment of obesity, there is agreement that the surgical procedure should: a) be safe (mortality < 1%, morbidity < 10%); b) be useful for 75% of patients (loss of excess weight > 50%, target BMI < 35 kg/m²); c) be durable (benefit persisting beyond five years); d) be reproducible by most surgeons, easy learning curve; e) offer good quality of life; f) require few revisions (< 2% of reinterventions annually); g) have minimal side effects; and h) be easily reversible (from an anatomical or functional perspective). We consider that all these criteria should be applicable to bariatric endoscopy, bearing in mind that effectiveness and benefit durability might be lower, as this represents a less aggressive, radical approach; endorsing its viability because of better tolerance, fewer complications, and potential for sequential therapies to optimize clinical outcome; and assuming that a weight loss of around 10% already prevents or reduces the risk for cardiovascular conditions and other comorbidities 15.

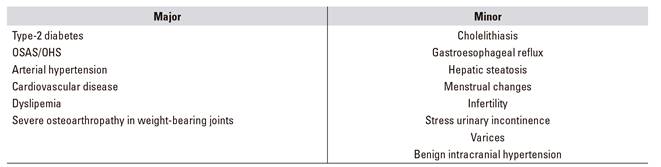

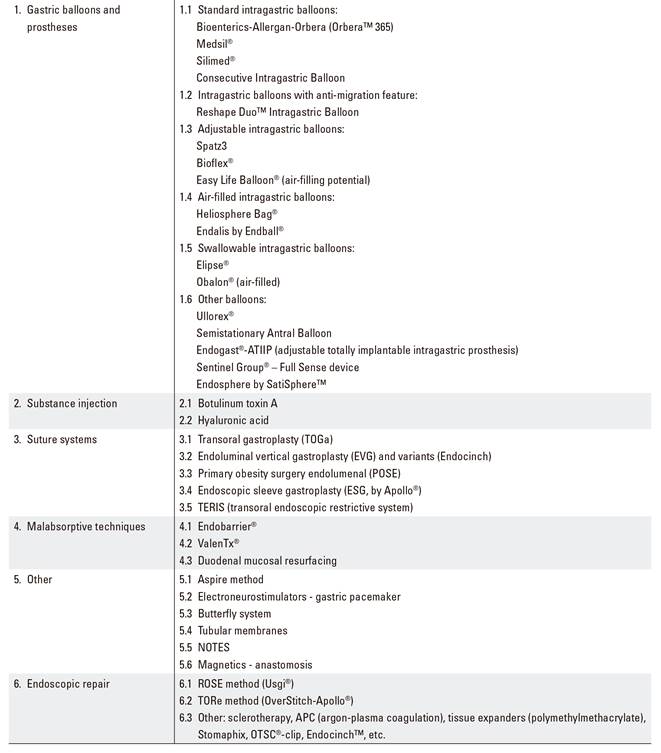

Over the last few years a number of endoluminal endoscopic techniques emerged, which to a large extent attempted to replicate the anatomic changes induced by bariatric surgery; less invasive and more cost-effective, their initial results look promising 16,17 (Table 3). All bariatric endoscopic procedures must be performed in specialist, accredited endoscopy units with adequate structural and human resources. Close multidisciplinary coordination must be available with nutrition/dietetics, endocrinology and/or anesthesiology departments. An around-the-clock Emergency Room with endoscopic and surgical capabilities, staffed by experts in obesity, should be available to solve potential complications 18. Moreover, liaison with psychology or psychiatry services for the assessment and/or follow-up of selected patients is advisable.

Table 3 Main endoscopic alternatives currently available for the management of obesity (modified from Espinet-Coll et al. 16))

CONSENSUS DOCUMENT. GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

Indications and contraindications of endoscopic obesity treatment

Obesity is a chronic multifactorial disease with no currently available cure. Dietary re-education, lifestyle modification, and physical exercise (key treatment components together with drug therapy and/or specialist psychological support) are estimated to result in weight losses of only 10% (mean loss, 5 kg) mid-term 19,20, which often are reversed within the next five years 21,22. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) consensus conference convened in 1991 concluded that "diet alone cannot be considered a reasonable option to achieve steady weight loss" 23. Until recently, bariatric surgery was the only treatment able to improve long-term expectations, primarily in subjects with morbid obesity. However, less than 1-2% of obese patients potentially eligible for bariatric surgery eventually undergo these procedures 10. Furthermore, mean weight regains involving over 30% of lost weight are commonly seen at ten years after surgical gastric bypass, with almost all weight regains affecting 25% of individuals 24,25.

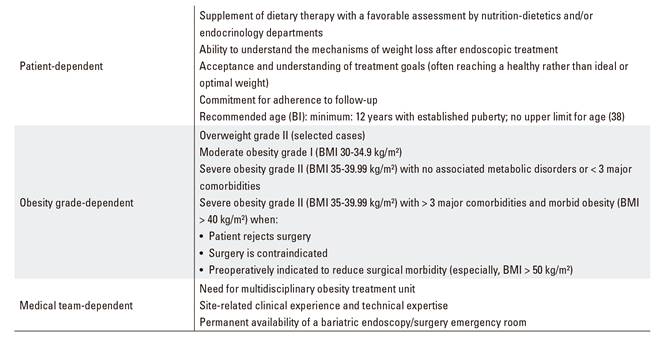

A number of endoscopic treatments for obese patients not eligible for surgery who respond insufficiently to medical therapy alone have been developed, and become popular, in the last few years 16,17. These are basically patients with grade-II overweight, or grade-I/II obesity, failing to respond to medical therapy, or undergoing bariatric endoscopy to supplement medical therapy 26,27,28,29. Patients with morbid obesity (grade III/IV) who reject surgery, or where surgery is contraindicated or entails excessive risk, might also benefit from endoscopic treatment. Finally, patients with morbid obesity (mainly superobesity with BMI > 50 kg/m2) requiring preoperative weight loss to reduce bariatric surgery-related morbidity are also eligible for endoscopic treatment 29,30,31,32,33,34. Table 4 lists the selection criteria that, in our view, should be used for patients who are candidates to metabolism- or obesity-related endoscopic treatment. Each patient should be individually assessed by a multidisplinary team.

Studies are now being designed to research potential predictive factors of good response for each bariatric endoscopy procedure: age, sex, social status, gastric emptying, hormone levels, etc., which might contribute to facilitate improved patient and endoscopic modality selection, hence optimized results.

There is a subgroup of patients who, having previously undergone bariatric surgery (primarily gastric bypass), experience stoma and pouch dilation over time, which favors weight regain. Endoscopic repair techniques are available for these patients, which allow to endoscopically reduce the diameter of these structures, and ease these individuals back into their weight loss curve 35,36,37.

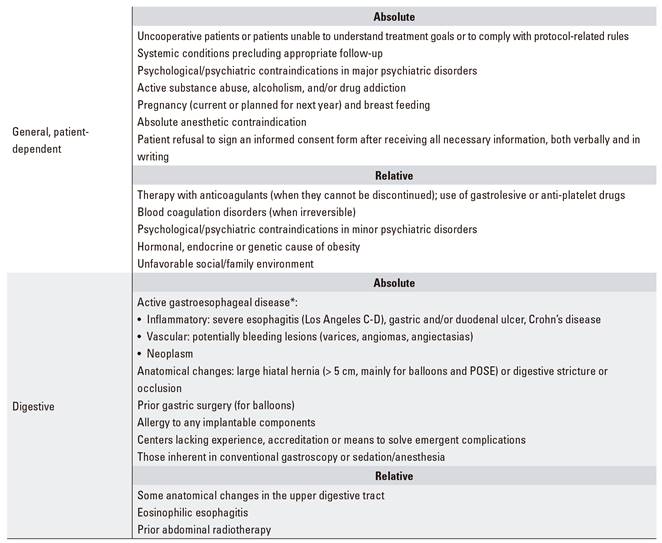

In some clinical, laboratory, or endoscopic settings endoscopic obesity treatment may be contraindicated (Table 5). Performing these therapies in centers without adequate infrastructure, accredited minimal experience, or capability to overcome potential complications is also deemed inadvisable.

Prior study, assessment and examinations. Informed consent

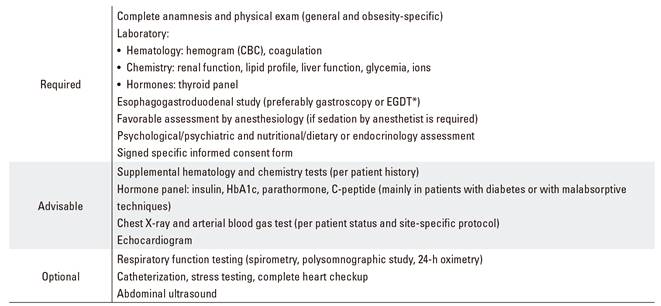

The following prior assessment should be performed for all patients meeting the criteria of and eligible to undergo endoscopic obesity treatment (Table 6):

Table 6 Recommended assessments before endoscopic treatment

*EGDT: radiographic esophagogastroduodenal transit.

Medical assessment, which should include:

Anamnesis and physical examination: general and obesity-specific.

Diagnostic tests: protocolized, specific study (Table 6). In the absence of gastric exclusion, routine H. pylori eradication is not required unless the patient's medical history or previous endoscopic mucosal findings make it advisable. Therefore, infection with H. pylori represents no contraindication for bariatric endoscopy 38.

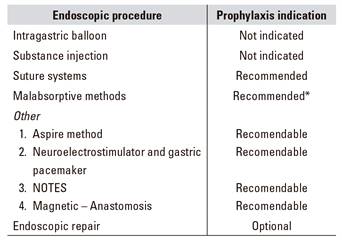

Recommendations: the treating doctor should discuss the endoscopic technique of his or her choice with the patient, including results to be expected (the ideal goal may not always be reached despite appropriate technique and follow-up), alternatives available, and potential adverse effects and complications. While no consensus exists, depending on endoscopic technique a decision should be made whether antibiotic prophylaxis is required (Table 7), mainly when sutures or anchors are full thickness and across the mucosa are used and for ostomies.

Table 7 Antibiotic prophylaxis in bariatric endoscopy

*Primarily when anchors go across the serous layer. Parenteral (i.m. or i.v.) route, 30 minutes before endoscopy: ampicillin i.m. or i.v. 2 g. In case of penicillin allergy, assess: cefazolin i.m. or i.v. 1 g or cefotaxime i.v. 2 g; vancomycin i.v. 1 g.

Nutritional, dietary, and/or endocrine assessment: anthropometry, nutrition habits, physical activity. Dietary, physical exercise, and lifestyle changes to be introduced after endoscopic treatment will be assessed and discussed.

Psychological assessment: any psychological conditions that might difficult or contraindicate adequate medico-dietary follow-up after endoscopy should be assessed. This should include a semi-structured interview dealing with the history, dietary symptoms, and current status of the condition. A psychometric study should also be carried out with questionnaires on eating disorder symptoms (EAT-40, EDI-II, BITE), associated psychopathology (SCL-90-R, BDI), and personality issues (TCI-R).

Anesthesiologic assessment: overall, it is recommended that sedation for obese patients be performed by an experienced anesthetist, since most of these individuals are ASA-III because of their weight issue and common metabolic comorbidities. A thorough preanesthetic assessment should be carried out to establish the type of sedation (superficial, deep, orotracheal intubation [OTI]) and drugs that will be administered. Most important in this setting is an evaluation of the patient's respiratory, cardiovascular, digestive, and endocrine-metabolic systems. In selected cases, the endoscopist may perform the sedation procedure with the help of a specifically trained nurse 39.

Endoscopic assessment: all patients should previously undergo an esophago-gastro-duodenal assessment with an esophago-gastro-duodenal radiologic transit study or, ideally, an esophagogastroduodenoscopy to rule out organic lesions that might pose a challenge to or contraindicate the intended bariatric procedure.

Prior assessment must include a specific informed consent form for each endoscopic technique, including details on the indication, favorable results of previous assessment, procedure characteristics, outcomes to be expected (including potential failure despite appropriate indication and follow-up), available alternatives, risks, potential adverse effects, and both technique-related and patient-related complications. Including a recommendation of, and patient commitment to, protocolized medical-dietary follow-up after the procedure is advisable. For reversible procedures (balloons, prostheses, etc.) an approximate date of explantation should be included. Consent must be obtained verbally and in writing, and consent withdrawal should be included as an option. The form should be signed by the physician administering the informed consent, the endoscopist involved, and the patient; if feasible, also by a patient's witness. The form should be given to the patient with sufficient time to read and understand its contents, and to answer any questions or concerns the patient may have, ideally, at least 24 hours before the procedure 40,41.

It is advisable to annex an additional informed consent form to authorize the potential inclusion of images in the endoscopy report and in scientific journals, meetings and conferences anonymously, for medical-scientific purposes, and over an unlimited period of time 40.

Refusal to undergo any previous study or to sign the informed consent will formally contraindicate the suggested endoscopic technique.

Quality criteria and outcome assessment

The goal of bariatric endoscopy is to supplement dietary therapy in order to correct or control both obesity and its associated metabolic conditions, which in turn will improve quality of life. Agreeing with the patient the endoscopy technique better suited to meet his or her needs, taking patient preferences and site experience and resource availability into consideration, is of utmost importance.

In order to obtain a good level of satisfaction it is important to agree a real weight target with the patient from the very outset, advising against ideal weight targets that often prove almost impossible to reach. It should be remembered that weight loss above 10% is highly beneficial in terms of cardiovascular disease prevention 15, and that reducing excess weight by 35% actually resolves most comorbidities associated with early mortality 42.

In April 2003, Deitel and Greenstein published in Obesity Surgery 43 recommendations to adequately express weight loss using the following:

Percentage of overweight / excess weight loss (%EWL)

Percentage of BMI loss (%BMIL)

Percentage of excess BMI loss (%EBMIL)

100 - [Final BMI - 25) / (Initial BMI - 25) x 100]

(Initial BMI - Current BMI) / (Initial BMI - 25) x 100

Recent reviews further recommend that results be expressed as percentage of total body weight loss (%TBWL).

In parallel with Fobi-Baltasar criteria, which are used in bariatric surgery 12,13,14, we may compile a number of characteristics and requirements to define an ideal endoscopic technique:

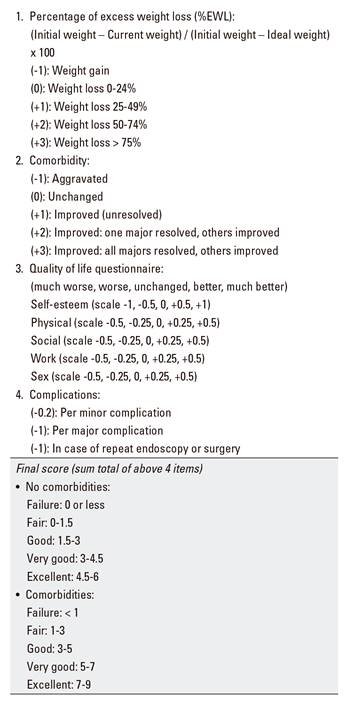

Efficacy: useful in 75% of patients with minimal excess weight loss (EWL) above 25% and/or with improved (particularly major) comorbidities, quality of life, and dietary habits. This may be measured, for instance, using the Bariatric Analysis and Reporting Outcome System (BAROS) scale as adapted to endoscopic treatment 42,43,45 (Table 9). Outcomes might thus be defined as: Excellent: EWL > 75% or EBMIL > 65%. Good: EWL 50-74% or EBMIL 50-65%. Fair/Acceptable: EWL 25-49% or EBMIL 25-49%. Poor: EWL < 25% or EBMIL < 25%. Results should be expressed using the standard deviation of estimations (rather than upper and lower limits), number of patients involved, and number of patients at each study time point.

Duration: since endoscopic treatment is less aggressive and radical than surgical treatment, the fact that equal long-term benefits are not to be expected stands to reason. In our view, we should pursue at least mid-term results, that is, through one year after explantation for reversible procedures (balloons, prostheses, etc.) and above two years for irreversible procedures (suture systems, etc.), also detailing the percentage of patients lost to follow-up during the period involved. The potential use of sequential endoscopic treatments may manage to sustain or increase favorable efficacy results mid- or long-term.

Reproducibility by most specifically trained endoscopists. "Doctor-to-doctor" training should be established in reference sites. Learning curves differ for the various techniques and, in our view, training should ensue as follows: five balloon procedures under supervision, ten endoscopic repairs, and 15 procedures using malabsorptive techniques and primary sutures. A minimum load of patients/month should be required for a center to maintain their accreditation (estimated minimum of 30 treatments/year).

Tolerability: good tolerability with adequate quality of life, especially regarding food intolerance, vomiting or diarrhea after 72 hours post-procedure.

Need for few revisions (< 1% of reinterventions after one year).

Few side effects, most of them mild, transient effects with response to and resolution with conservative medical therapy.

Reversible, either anatomically or functionally.

As a patient-centered quality marker, following the procedure all patients should be provided with a real-time, typewritten discharge report including specific recommendations and scheduled care and follow-up visits.

Every center should keep a record of complications and adverse events for each procedure performed, including severity and resolution characteristics.

Multidisciplinary follow-up: dietary and psychological assessment. Lifestyle modification. Other specialties involved

The first step in the treatment of obesity is improving feeding habits and increasing physical activity to reduce fat. Mid-term, the aim is to maintain the weight loss achieved and to reduce associated complications and metabolic conditions. To meet this end, regular follow-up by a dietician is important 38, and further follow-up by a specialized psychologist is recommended.

By way of guidance, and according to the surgical protocol 46, a minimum follow-up schedule would consist of visits at 15 days and 1, 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months after the procedure, and in the absence of complications, annual review visits thereafter. In addition to weight losses, comorbidity course/improvement and medication reduction/discontinuation should also be recorded.

Eating plan

Regular follow-up by a nutrition, dietetics specialist, not necessarily an endocrinologist, is key for success 38. Overall, diet should be individualized according to patient characteristics (age, sex, comorbidities, job, preferences, time schedule, etc.) and the procedure performed (particularly during the initial adjustment period: liquid diet, progressive diet, etc.).

While non-strict diets are presently recommended, an intake of 1,200-1,500 kcal/day is recommended, with varied contents and balanced nutrients: 55% carbohydrates (mostly complex), 20-30% lipids (< 10% saturated, > 10% monounsaturated, rest polyunsaturated fat), and 15-25% proteins. Furthermore, water is recommended with a minimum intake of 1.5 liters/day. Diets with very low calorie contents must be prescribed under stringent medical supervision, for periods shorter than 60 days, and occasionally for early morbid obesity and refractory obesity.

Physical exercise is important, and should be adapted to patient age and fitness by combining daily activities (walking, stair climbing, etc.) with aerobic (walking, swimming, running, dancing, cycling, etc.) and/or anaerobic (weightlifting, speed running, tennis, martial arts, etc.).

While more frequent diet-adjusting visits are usually required during the first month after the procedure, we recommend regular follow-up, tentatively on a monthly or bi-monthly basis, according to the needs of each individual patient. Patients with reversible devices (balloons, prostheses) must be followed on until device removal, including an optional minimum follow-up for one year thereafter. Patients undergoing irreversible or definitive procedures (suture systems) should be offered follow-up for at least two years.

Psychological management

Initial psychological assessment is indispensable for obese patients. Psychological follow-up is also usually recommended, and it has been associated with increased effectiveness and both mental and physical quality of life, and is strictly necessary when severe personality, anxiety, or depressive disorders are present.

Individual, group, or family psychoeducational counselling or cognitive-behavioral therapy may be used to enhance patient support, motivation, adherence to recommended meal plan, positive stimulation, self-esteem, anxiety suppression, and improved body image.

Drug therapy

Bariatric endoscopy must be considered as a supplement to hygienic-dietary treatment, and in this context drug therapy is restricted to tolerance optimization within the first few hours. However, new drugs are being investigated that might help maintain weight loss following endoscopy.

In general, drug supplementation of dietary measures is not an indication today, neither as a primary target for obesity nor as a supplement for nutritional deficiencies.

Other specialties involved

Depending on the present underlying conditions and comorbidities, it is recommended that patients undergo parallel follow-up by their specialists for each associated disorder for the duration of the endoscopic device.

It is essential that patients be aware of and have open access to a 24-hour emergency service staffed by an endoscopist and surgeon experienced in the management of potential complications 18.

Scientific development and research

It is recommended that bariatric endoscopy units meet minimum requirements to accredit sufficient training capabilities for bariatric endoscopists in different endoscopic techniques. They should as far as possible accept and train endoscopists interested in mastering bariatric procedures.

Endoscopists should work within a team, with enough workload to guarantee adequate results in terms of safety and effectiveness (a minimum of 30 treatments/year is recommended), with obesity-related clinical sessions, preferably including all professionals involved in the management of obese patients.

They should keep up-to-date in bariatric knowledge by participating in bariatric endoscopy societies, attending courses and meetings on obesity, discussing their results (both favorable and untoward) in various scientific fora, publishing papers in specialist journals, and taking part in the development of renowned books and manuals on obesity.

They should demonstrate enough research capacity and experience to facilitate the development of novel bariatric endoscopy techniques. Predisposition to collaborate with other sites for the benefit and advancement of bariatric endoscopy is also essential.

Compliance with these rules may in the future facilitate accreditation for bariatric endoscopy units.

Structural resources of a bariatric endoscopy unit

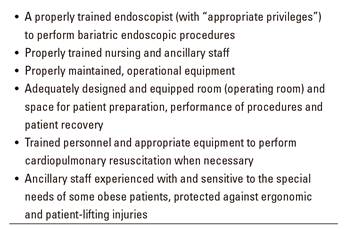

Patients with obesity require more and more varied health care resources, both structural and human, as compared to non-obese individuals. In this regard, bariatric endoscopy units must address special design and equipment needs always in compliance with the regulations set forth by the Ministry of Health and/or regional health care authority.

Currently, most endoscopy units do not include specific protocols for obese patients. However, hospital endoscopy units with bariatric surgery and/or endoscopy programs are expected to be fitted with all the necessary items to ensure proper obese patient care 47, including appropriate and adapted furniture, equipments, and medical-endoscopic instruments (Table 10). A bariatric endoscopy accreditation system should be considered, as suggested by the SEEDO 48, for centers meeting these rules.

Table 10 Requirements for safe and effective gastrointestinal and bariatric endoscopy (adapted from C. Thompson, MD, PhD; Harvard Medical School 47))

We classified the required resources into three distinct categories: a) offices and common areas; b) endoscopy area; and c) human resources.

Offices and common hospital areas

The reception-access area should have furniture, doors, bathrooms, and wheelchairs appropriate and comfortable for obese patients and their families. Family members of obese patients are usually obese too, and their lodging facilities when accompanying their relatives should also be taken into consideration.

The outpatient clinic should also be well differentiated, and have a sufficient weekly workload. Adapted materials include: scales capable of measuring up to 200 kg, sphygmomanometers with assorted cuffs (including extra-large sizes), reinforced gurneys, adapted beds, etc. It is recommended that body composition be established with dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA), bioelectrical impedance, or other widely recognized method. Laboratory, electrocardiogram (ECG), and imaging test areas should also be easily accessible for obese individuals.

Radiology rooms should include equipment capable of testing obese patients (weighing over 200 kg); manufacturer specs should be documented and made available to the involved staff 49.

As regards bathrooms, while the American Institute of Architects (AIA) issued specific recommendations, we could find no such guidelines in Spain. In the US, floor-mounted toilets with a drop weight rating of 700 lb (317 kg) and a clearance of five feet (1,520 mm) are recommended 50. Wall-mounted, reinforced sinks with a weight rating of 300 lb (136 kg) are also recommended.

Specific systems developed for safe patient mobilization and transfer should be available, including appropriate ergonomics, ample free space around beds and seats, elevators and lifts. The staff must be trained to operate these devices and to shuttle these patients without injuring them or themselves.

Endoscopy area

In the endoscopy area doors, corridors, and preparation/recovery rooms must be larger than standard, and allow the passage and maneuvering of large beds, gurneys and wheelchairs. Patient and staff safety must be considered in its layout.

Examination rooms

Size: an endoscopy room should have at least enough square meters to accommodate endoscopy (videoendoscope, monitors, etc.), anesthesia, and occasionally radiology (51,52) equipment and materials, hence it is recommended that procedures be carried out when possible in a specifically designed endoscopy room, an interventionist room, or an operating room.

Gurneys: in addition to transportation, gurneys must also serve as examination tables or table carts. This is very important for the system and its overall efficiency, and adds to patient safety by avoiding patient transfers to and from examination tables.

Endoscopy team: we consider that any hospital including a bariatric surgery or obesity unit should also have a specific bariatric endoscopy unit addressing the following:

Diagnostic endoscopy for the preoperative assessment of patients eligible for bariatric surgical or endoscopic treatment.

Management of postoperative complications (strictures, fistulae, leaks, bleeding, etc.) and revision procedures (stoma closure, etc.) after bariatric surgery, which are increasingly addressed in a less invasive manner, that is, endoscopically 50,51,52,53,54,55.

Primary endoscopic treatment of obesity, an emerging setting that includes a wide variety of procedures presently available in our country (Table 3).

Endoscopes

A conventional gastroscope suffices for the preoperative assessment of patients eligible for bariatric endoscopy or surgery, as well as for most primary endoscopic obesity treatments (mostly balloons, prostheses, substance injections, sleeves).

Also for most patients with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery a standard gastroscope is enough to assess the esophagus, gastric pouch, gastro-jejunal anastomosis, and proximal Roux loop. A pediatric gauge colonoscope or an enteroscope may be necessary to evaluate the jejuno-jejunal anastomosis. In case of ERCP, balloon enteroscopy may facilitate examination of the biliopancreatic loop and excluded stomach 55. Other options are available for a transparietal hepatic approach or laparoscopy-assisted transgastric ERCP (primarily when cholecystectomy is required).

Special endoscopes are required for some primary suture systems and for surgical stomas repairs. Thus, Usgi(r) suture anchors (POSE method, ROSE repair) require an ultrathin gastroscope < 5 mm in diameter, whereas the OverStitch-Apollo(r) system (vertical gastroplasty or TORe repair) requires a dual channel gastroscope (currently only feasible with Olympus Medical devices: GIF-2T160, GIF-2T180 or GIF-2T240).

Accessories

Bariatric endoscopy, whether elective or emergency, requires endoscopic accessories as usually available in endoscopy units, including overtubes, foreign body forceps, endoscopic hoods, hemostatics, etc. For prolonged procedures (using primarily suture methods), insufflation with CO2 seems to reduce bloating and discomfort, and should thus be made available 55.

For post-gastric bypass endoscopy revision, and for complications such as bleeding, strictures, fistulae, and dehiscence, a variety of endoscopic clips, dilators, stents, glues, sutures, and thermal or abrasive devices may be used.

Furthermore, each primary bariatric endoscopy approach may require specific accessories that will be specifically designed.

Human resources

Staffing models should be developed and sustained to provide an efficient staff/patient ratio. There should be sufficient staff to properly assist in the preparation, procedure, recovery, ambulation, transfer, and mobilization of obese patients.

According to the SEEDO, an obesity unit should be headed by a physician adequately trained and experienced in this field, and made up of at least three professionals with at least three years of documented experience. We consider that a bariatric endoscopy unit should include at least two endoscopists with bariatric expertise, two qualified nurses/assistants, an anesthetist specialized in sedation for obese patients, and two porters available for the endoscopy room. There should be direct liaison with a nutritionist/dietician and/or endocrinologist to provide adequate patient follow-up, and with the Psychology/Psychiatry Department. It is key that the unit be part of or in direct contact with a hospital to provide hospitalization wards, 24-hour emergency care, and endoscopists and surgeons with experience in bariatric complications to also provide post-procedure care, treatment, and follow-up, and/or solve potential complications.

Similarly, units performing bariatric endoscopy procedures on a regular basis should offer training opportunities for interested professionals (see "Scientific development and research"), with "doctor-to-doctor" training being particularly recommended. In the near future, some endoscopy units meeting minimal requirements might be accredited as bariatric endoscopy units.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This Consensus Document was presented, discussed, and approved during the "XXXVII Jornada Nacional de la Sociedad Española de Endoscopia Digestiva" (Zaragoza, Spain, November 2015) with the participation of the following specialist physicians: Drs. Abad Belando, Calahorra Medrano, Castellot Martín, Cervera Centelles, Ducons García, Espinet Coll, León Montañés, Mata Bilono, Nebreda Durán, Rodríguez Téllez, Sánchez Gómez, Sánchez Muñoz, Silva González, Turró Arau, Vascónez Peña, Vázquez Sequeiros and Vicente Benede.

Reviewed by Dr. Andrés J. Acosta Cárdenas, M.D., Ph.D., Clinical Enteric Neuroscience Translational and Epidemiological Research (C.E.N.T.E.R.), Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, USA, and by Dr. Ferrán González-Huix, President (currently ex-President), Spanish Society of Digestive Endoscopy (SEED), Digestive Endoscopy Unit, Hospital Arnau de Vilanova, Lérida, Catalonia, Spain.

REFERENCES

1. Organización Mundial de la Salud. Obesidad y sobrepeso. Nota descriptiva nº 311. Génova: OMS; 2006. [ Links ]

2 .World Health Organization. Diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases. Report of a Joint FAO/WHO Expert consultation. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 2003;916:1-149. [ Links ]

3. Aranceta-Bartrina J, Serra-Majem L, Foz-Sala M, et al.; grupo colaborativo SEEDO. Prevalencia de obesidad en España. Med Clin (Barc) 2005;125:460-6. DOI: 10.1157/13079612 [ Links ]

4. Ruhm CJ. Current and future prevalence of obesity and severe obesity in the United States (June 2007). Natural Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) working paper no. 13181. [ Links ]

5. Estudio prospectivo Delphi. Costes sociales y económicos de la obesidad y sus patologías asociadas (hipertensión, hiperlipidemias y diabetes). Madrid: Gabinete de Estudios Sociológicos Bernard Krief; 1999. [ Links ]

6. Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, et al. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA 2004;291:1238-45. DOI: 10.1001/jama.291.10.1238 [ Links ]

7. Garrow JS, Webster J. Quetelet's index as a measure of fatness. Int J Obes 1985;9:147-53. [ Links ]

8. World Health Organization. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation on obesity. WHO/NUT/NCD/98.1. Geneva: WHO Technical Support Series; 1998. pp. 1-276. [ Links ]

9. National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute Education Initiative (review). Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults. The evidence report. Obes Res 1998;6(Suppl. 2):51S-209S. [ Links ]

10. Buchwald H, Oien DM. Metabolic/bariatric surgery worldwide 2011. Obes Surg 2013;23:427-36. DOI: 10.1007/s11695-012-0864-0 [ Links ]

11. Chang SH, Stoll CR, Song J, et al. The effectiveness and risks of bariatric surgery: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis, 2003-2012. JAMA Surg 2014;149:275-87. DOI: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.3654 [ Links ]

12. Larrad A, Sánchez-Cabezudo C. Indicadores de calidad en cirugía bariátrica y criterios de éxito a largo plazo. Cir Esp 2004;75:301-4. DOI: 10.1016/S0009-739X(04)72326-X [ Links ]

13. Fobi MAL. The Fobi pouch operation for obesity. Booklet. Quebec: 13th Annual Meeting ASBS; 1996. [ Links ]

14. Baltasar A, Bou R, Del Rio J, et al. Cirugía bariátrica: resultados a largo plazo de la gastroplastia vertical anillada. ¿Una esperanza frustrada? Cir Esp 1997;62:175-9. [ Links ]

15. Pi-Sunyer FX. A review of long-term studies evaluating the efficacy of weight loss in ameliorating disorders associated with obesity. Clin Ther 1996;18:1006-35. DOI: 10.1016/S0149-2918(96)80057-9 [ Links ]

16. Espinet-Coll E, Nebreda-Durán J, Gómez-Valero A, et al. Técnicas endoscópicas actuales en el tratamiento de la obesidad. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2012;104:72-87. DOI: 10.4321/S1130-01082012000200006 [ Links ]

17. Abu Dayyeh BK, Sarmiento R, Rajan E, et al. Tratamiento endoscópico de la obesidad y los trastornos metabólicos: ¿una realidad? Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2014;107:467-76. [ Links ]

18. García Ruiz De Gordejuela A, Madrazo González Z, Casajoana Badia A, et al. Descripción de la asistencia en urgencias de pacientes intervenidos de cirugía bariátrica en un centro de referencia. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2015;107:23-8. [ Links ]

19. Anderson JW, Konz EC, Frederich RC, et al. Long-term weight-loss maintenance: A meta-analysis of US studies. Am J Clin Nutr 2001;74:579-84. DOI: 10.1093/ajcn/74.5.579 [ Links ]

20. Padwal R, Li SK, Lau DCW. Long-term pharmacotherapy for overweight and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Obes 2003;27:1437-46. DOI: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802475 [ Links ]

21. Wadden TA, Sternberg JA, Letizia KA, et al. Treatment of obesity by very low calorie diet, behaviour therapy, and their combination: a five-year perspective. Int J Obes 1989;13:39-46. [ Links ]

22. Sumithran P, Prendergast LA, Delbridge E, et al. Long-term persistence of hormonal adaptations to weight loss. N Engl J Med 2011;365:1597-604. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105816 [ Links ]

23. Gastrointestinal surgery for severe obesity: National Institute of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement. Am J Clin Nutr 1992;55:615S-9S. [ Links ]

24. Christou N, Look D, Maclean LD. Weight gain after short- and long-limb gastric bypass in patients followed for longer than 10 years. Ann Surg 2006;244:734-40. DOI: 10.1097/01.sla.0000217592.04061.d5 [ Links ]

25. Sjöström L, Lindroos A, Peltonen M, et al. Lifestyle, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk factors 10 years after bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med 2004;351:2683-93. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa035622 [ Links ]

26. Doldi SB, Micheletto G, Perrini MN, et al. Intragastric balloon: another option for treatment of obesity and morbid obesity. Hepatogastroenterology 2004;51:294-7. [ Links ]

27. Carbonelli MG, Fusco MA, Cannistra F, et al. Body composition modification in obese patients treated with intragastric balloon. Acta Diabetol 2003;40:S261-2. DOI: 10.1007/s00592-003-0081-3 [ Links ]

28. Roman S, Napoléon B, Mion F, et al. Intragastric balloon for "non-morbid" obesity: a retrospective evaluation of tolerance and efficacy. Obes Surg 2004;14:539-44. DOI: 10.1381/096089204323013587 [ Links ]

29. Tsesmeli N, Coumaros D. Review of endoscopic devices for weight reduction: old and new balloons and implantable prostheses. Endoscopy 2009;41:1082-9. DOI: 10.1055/s-0029-1215269 [ Links ]

30. Zago S, Kornmuller AM, Agagliato D, et al. Benefit from bio-enteric intra-gastric balloon (BIB) to modify lifestyle and eating habits in severely obese patients eligible for bariatric surgery. Minerva Med 2006;97:51-64. [ Links ]

31. Genco A, Cipriano M, Bacci V, et al. BioEnterics Intragastric Balloon (BIB): a short-term, double-blind, randomised, controlled, crossover study on weight reduction in morbidly obese patients. Int J Obes 2006;30:129-33. DOI: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803094 [ Links ]

32. De Waele B, Reynaert H, Urbain D, et al. Intragastric balloons for preoperative weight reduction. Obes Surg 2000;10:58-60. DOI: 10.1381/09608920060674139 [ Links ]

33. Evans JD, Scott MH. Intragastric balloon in the treatment of patients with morbid obesity. Br J Surg 2001;88:1245-8. DOI: 10.1046/j.0007-1323.2001.01840.x [ Links ]

34. Alfalah H, Philippe B, Ghazal F, et al. Intragastric balloon for preoperative weight reduction in candidates for laparoscopic gastric bypass with massive obesity. Obes Surg 2006;16:147-50. DOI: 10.1381/096089206775565104 [ Links ]

35. Espinet Coll E, López-Nava Breviere G, Nebreda Durán J, et al. Eficacia y seguridad del TORe mediante sutura endoscópica para tratar la reganancia ponderal tras bypass gástrico quirúrgico en Y-de-Roux. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2018. En prensa. DOI: 10.17235/reed.2018.5419/2017 [ Links ]

36. Gitelis M, Ujiki M, Farwell L, et al. Six month outcomes in patients experiencing weight gain after gastric bypass who underwent gastrojejunal revision using an endoluminal suturing device. Surg Endosc 2015;29:2133-40. DOI: 10.1007/s00464-014-3954-3 [ Links ]

37. Jirapinyo P, Slattery J, Ryan MB, et al. Evaluation of an endoscopic suturing device for transoral outlet reduction in patients with weight regain following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Endoscopy 2013;45:532-6. DOI: 10.1055/s-0032-1326638 [ Links ]

38. Neto MG, Silva LB, Grecco E, et al. Brazilian Intragastric Balloon Consensus Statement (BIBC): practical guidelines based on experience of over 40,000 cases. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2018;14(2):151-9. DOI: 10.1016/j.soard.2017.09.528. [ Links ]

39. Igea F, Casellas JA, González-Huix F, et al. Sedación en endoscopia digestiva. Guía de práctica clínica de la Sociedad Española de Endoscopia Digestiva. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2014;106:195-211. [ Links ]

40. Dolz Abadía C. Consentimiento informado en endoscopia digestiva: información para el paciente, protección para el endoscopista. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2016;108:13-23. [ Links ]

41. Nebreda Durán J, Espinet Coll E. GETTEMO position statement on bariatric endoscopic techniques as a voluntary medicine. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2017;109(12):875-6. DOI: 10.17235/reed.2017.5144/2017 [ Links ]

42. Deitel M. How much weight loss is sufficient to overcome major co-morbidities? Obes Surg 2001;11:659. [ Links ]

43. Deitel M, Greenstein RJ. Recommendations for reporting weight loss. Obes Surg 2003;13:159-60. DOI: 10.1381/096089203764467117 [ Links ]

44. Espinet E, Nebreda J, López-Nava G, et al. Multicenter study on the safety of bariatric endoscopy. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2017;109(5):350-7. DOI: 10.17235/reed.2017.4499/2016 [ Links ]

45. Oria HE, Moorehead MK. Bariatric analysis and reporting outcome system (BAROS). Obes Surg 1998;8:487-99. DOI: 10.1381/096089298765554043 [ Links ]

46. Rubio MA, Martínez C, Vidal O, et al. Documento de consenso sobre cirugía bariátrica. Rev Esp Obes 2004;4:223-49. [ Links ]

47. Thompson CC, editor. Bariatric Endoscopy (eBook). Springer New York Heidelberg Dordrecht London. Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA. NY: Springer; 2013. [ Links ]

48. Sociedad Española para el Estudio de la Obesidad (SEEDO). Criterios de reconocimiento de una unidad hospitalaria de obesidad. Acceso 19-9-2014. Disponible en: http://www.seedo.es/images/site/documentacionConsenso/Criterios-de-reconocimiento-de-una-unidad-hospitalaria.pdf. [ Links ]

49. Brethauer SA, Chand B, Schauer PR, et al. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) Centers of Excellence Program. En: Nguyen NT, Maria EJ, Ikramuddin S, Hutter MM, eds. The SAGES manual. New York: Springer; 2008. pp. 257-60. [ Links ]

50. Andrew Collignon JD, American Institute of Architects (AIA). Strategies for accommodating obese patients in an acute care setting - Planning and design guidelines for bariatric healthcare facilities: 2004-2005. Spring 2008. Acceso 10-01-2016. Disponible en: http://www.aia.org/aiaucmp/groups/aia/documents/pdf/aiab090827.pdf [ Links ]

51. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Establishment of gastrointestinal endoscopy areas. Gastrointest Endosc 1999;50:910-2. DOI: 10.1016/S0016-5107(99)70193-8 [ Links ]

52. Marasco JA, Marasco RF. Designing the ambulatory endoscopy center. Ambulatory endoscopy centers. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2002;12:185-204. DOI: 10.1016/S1052-5157(01)00002-2 [ Links ]

53. Harrell JW, Miller B. Big challenge: designing for the needs of bariatric patients. Health Facil Manage 2004;17(3):34-8. PMID: 15058082 [ Links ]

54. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Role of endoscopy in the bariatric surgery patient. Gastrointest Endosc 2008;68:1-10. DOI: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.01.028 [ Links ]

55. Joint Task Force Recommendations for Credentialing of Bariatric Surgeons. Guidelines for institutions granting bariatric privileges utilizing laparoscopic techniques. Guidelines Committee Society of American Gastrointestinal Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES). Acceso 19-9-2014. Disponible en: http://www.sages.org/publications/guidelines/guidelines-for-institutions-granting-bariatric-privileges-utilizing-laparoscopic-techniques/ [ Links ]

56. Acosta A, Camilleri M. The year in diabetes and obesity. Gastrointestinal morbidity in obesity. Ann NY Acad Sci 2014;1311:42-56. [ Links ]

57. SAGES Guidelines for office endoscopic services. 2010. Disponible en: http://www.sages.org/publication/id/09/ [ Links ]

58. SAGES Guidelines Committee Society of American Gastrointestinal Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES). [ Links ]

59. SAGES Guideline for clinical application of laparoscopic bariatric surgery. 2010. Disponible en: http://www.sages.org/ publication/id/30/ [ Links ]

60. Cir Esp. Recomendaciones de la SECO para la práctica de cirugía bariátrica (Declaración de Salamanca). Cir Esp 2004;75:312-4. [ Links ]

61. Conferencia de consenso. Consenso SEEDO'2000 para la evaluación del sobrepeso y la obesidad y el establecimiento de criterios de intervención terapéutica. Sociedad Española para el Estudio de la Obesidad (SEEDO). Med Clin (Barc) 2000;115:587-97. [ Links ]

62. ASGE Bariatric Endoscopy Task Force, Sullivan S, Kumar N, et al. ASGE position statement on endoscopic bariatric therapies in clinical practice. Gastrointest Endosc 2015;82:767-72. DOI: 10.1016/j.gie.2015. 06.038 [ Links ]

63. ASGE Bariatric Endoscopy Task Force, ASGE Technology Committee, Abu Dayyeh BK, et al. Endoscopic bariatric therapies. Gastrointest Endosc 2015;81:1073-86. DOI: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.02.023 [ Links ]

64. ASGE Bariatric Endoscopy Task Force, ASGE Technology Committee, Abu Dayyeh BK, et al. ASGE Bariatric Endoscopy Task Force systematic review and meta-analysis assessing the ASGE PIVI thresholds for adopting endoscopic bariatric therapies. Gastrointest Endosc 2015;82:425-38. DOI: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.03.1964 [ Links ]

Received: June 22, 2017; Accepted: March 19, 2018

text in

text in