My SciELO

Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

Print version ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.110 n.10 Madrid Oct. 2018

https://dx.doi.org/10.17235/reed.2018.5605/2018

ORIGINAL PAPERS

Economic evaluation of a population strategy for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C with direct-acting antivirals

1Unidad de Investigación AP-OSIs Gipuzkoa. Organización Sanitaria Integrada Alto Deba. Mondragón, Guipúzcoa. Spain

2Red de Investigación en Servicios de Salud en Enfermedades Crónicas (REDISSEC). Bilbao Spain

3Instituto de Investigación Biodonostia. San Sebastián, Donostia. Spain

4Instituto de Salud Pública de Navarra - IdiSNA. Pamplona. Spain

5CIBER Epidemiología y Salud Pública (CIBERESP). Madrid. Spain

6Departamento of Farmacia. Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra - IdiSNA. Pamplona. Spain

INTRODUCTION

The availability of the new direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C has significantly changed its natural history 1,2. Until 2012, the treatment was based on the use of peg-interferon and ribavirin, which achieved efficacy of 40% to 80%, depending on the genotype and stage of liver fibrosis, with marked side effects 3,4. In 2012, the first-generation DAAs (boceprevir and telaprevir) were introduced, improving efficacy but worsening the safety profile (5,6). The second generation of DAAs available in 2014, radically changed the therapeutic approach to chronic hepatitis C 7. The possibility of including these molecules in shorter, well tolerated interferon-free treatments with efficacies higher than 95% prompted the demand for treatment. At the same time, their high cost generated financial tensions in health systems, and in Spain, prompted the launch in March 2015 of the "Strategic Plan for Tackling Chronic Hepatitis C in the Spanish National Health System (SPCHC)" 8.

The SPCHC was accompanied by the largest budget in the history of Spanish health care to be directed at the pharmacological treatment of a specific disease 8. From the viewpoint of the economic evaluation, the problem was not the cost-effectiveness of the drugs, but their budgetary impact 8,9. The budget impact analysis (BIA) is a planning tool that estimates the expected changes in the spending of a health system after the adoption of a new intervention. It can be independent or part of a comprehensive economic evaluation, together with a cost-effectiveness study (CES) 9.

The CES based on clinical trials showed that the new DAAs were, in general, efficient from the perspective of the Spanish health system 2,10,11,12. However, important differences may appear between the real-world practice and clinical trials regarding parameters of efficacy, safety, consumption of healthcare resources, or cost of medicines. Moreover, the clinical and epidemiological heterogeneity of cases of chronic hepatitis C could also affect the cost-effectiveness of the new treatments 13. The lack of information from real-world practice about the therapeutic effectiveness of DAAs was noted in the SPCHC, and so, our study seeks to respond to it 8). Based on administrative, epidemiological and clinical databases, the resident population of Navarre with active hepatitis C virus infection has been monitored and information collected on the stage of liver fibrosis and its treatment and outcome 14. This information is the gateway to determining the economic and health-benefit impact of the new DAAs.

The objective of this study was the economic evaluation of the application of the SPCHC in Navarre in its first two years of operation by estimating the cost-effectiveness ratio and the BIA with the parameters obtained from clinical practice ("real-world data") in the population of patients with chronic hepatitis C treated with new DAAs.

METHODS

By means of a discrete events simulation model based on patient-level data, 15 the change produced in the natural history of hepatitis C by sustained viral response (SVR) was compared to an alternative without treatment. The model allowed the calculation of health outcomes measured in quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) and costs to obtain the cost-effectiveness ratio and budgetary impact from the perspective of the Navarre Health Service. The time horizon for the calculation of the cost-effectiveness ratio was patient lifetime and 30 years for the AIP. The application of the national strategy was compared with the alternative of the absence of treatment, since the SPCHC has established that the previous treatments are ineffective and new treatments should be gradually applied to all the patients 8. The CEA was performed at a discount of 3%, both for costs and for effectiveness, and without discount in the sensitivity analysis 16. For the AIP, no discount was applied to the cost estimates 9.

Study population

The population included the group of patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection with stable residence in Navarre who were treated with DAAs between April 1, 2015, and December 31, 2016. The model reproduced individually the clinical and epidemiological characteristics (sex, age, degree of fibrosis, coinfection by human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), SVR and cost of treatment) of each patient. The selected treatment was updated periodically, depending on the appearance of new treatments. The available therapeutic options were prioritized based on evidence of their efficacy and safety, as well as their cost, in order to select the most efficient options. The regimens used were chronologically sofosbuvir / simeprevir, ombitasvir / paritaprevir / ritonavir +/- dasabuvir, sofosbuvir / ledipasvir, elbasvir / grazoprevir or sofosbuvir / daclatasvir. In the case of genotype 3, the sofosbuvir / daclatasvir combination was used. Other more recent pangenotypic combinations were unavailable during the study period.

Discrete events simulation model

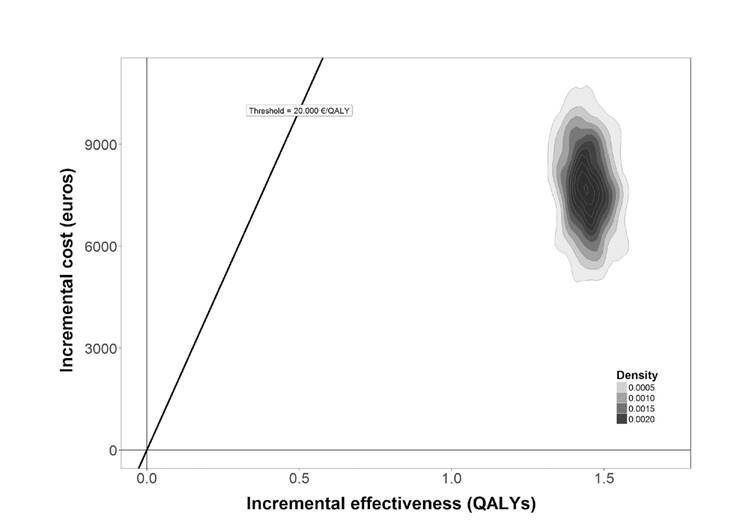

Discrete events simulation is a modeling technique that allows building of population models that can be used for both CEA and BIA 9,15,17. The software for the programming was R. The model was structured in two steps (Fig. 1). In the first, the patient's fibrosis evolves in stages through annual cycles until it reaches the first level of decompensated cirrhosis. These parameters were obtained from the international literature because of the lack of specific studies in the Spanish population. Transition probabilities among the different stages of fibrosis were adjusted by age and sex (1, 18). Subsequently, patients progressed from cirrhosis to decompensated cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma also on the basis of transition probabilities from the literature 18. In the second step, the phase of advanced chronic liver disease was modeled with parameters from a study that analyzed the survival of the different stages of decompensated cirrhosis in the Navarre population. This study allowed us to calculate the specific functions of time until the occurrence of new decompensation, hepatocarcinoma and liver transplantation 19. Based on cause, the initial decompensation was categorized into four groups: ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, bacterial infection and esophageal varices. Costs were calculated according to the number and type of re-hospitalization among patients with decompensated cirrhosis. As a probabilistic sensitivity analysis, 1000 simulations of the cohort of patients were carried out to obtain the cost-effectiveness plane 15,16. This plane is a diagram of the cost against the effectiveness of each simulation and consists of a scatter plot of points in which the values of the abscissa represent the incremental effectiveness (measured in QALYs) and the values of the ordinate axis the incremental cost (expressed in euros) 20.

Fig. 1 Flow diagram of the natural history model of hepatitis C (SVR: sustained viral response; HE: hepatic encephalopathy; GHPH: gastric hemorrhage due to portal hypertension; IB: bacterial infection).

Patients who achieved SVR were considered cured. In cases of fibrosis stages 3 and 4 with negative viremia, the progression of the disease towards decompensated cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma was maintained with a lower probability 18. However, patients with failed or no treatment evolved throughout the natural history of the disease. The model considered differential survival conditioned on the existence of coinfection with HIV 21. Extrahepatic mortality was incorporated in the model by assigning time to death by extrahepatic causes via a Gompertz parametric survival function calculated from the mortality rates of the general popu-lation of Navarre through a life density function 22. Given that the parameters were calculated in the general population, an adjustment was applied to patients with chronic hepatitis C by means of a hazard ratio, because their extrahepatic mortality rate is higher 23. Patients with decompensated cirrhosis on the waiting list for liver transplantation were treated with the new drugs according to the usual clinical practice. Transplant patients treated successfully were considered recovered, with an evolution equal to any patient transplanted for a cause other than infection by C virus 18.

Costs and utilities

The cost of the drugs varied according to the combinations used and decreased over the two years. For each patient in the study, the real cost of the therapeutic scheme was applied from the records of the Pharmacy Service.

To estimate the costs of disease progression, a distinction was made between transition or event costs and costs derived from each health state. The first corresponds to hospital care for complications of chronic liver disease, and the second includes the resources used during patient follow-up. The costs for patients admitted for decompensated cirrhosis, hepatocarcinoma and liver transplant were obtained from the fees for services provided by the Navarre Health Service, which were based on the classification of patients by diagnostic related groups (DRG) in 2014 24. The monitoring costs were calculated according to the usual medical practice and unit costs of the Navarre Health Service 24. The 12-week treatments included an initial medical visit and 4 subsequent visits at weeks 4, 8 and 12 and at 12 weeks post-treatment. Samples for biochemical analysis and blood count were included in all visits. The determination of the viral load was included at the initial visit, at weeks 4 and 12, and at 12 weeks post-treatment. The 24-week treatments included two additional visits in weeks 8 and 24, which included a biochemical analysis, blood count and a determination of viral load at week 24.

Each health state included in the model received a specific utility value according to the severity of the disease. In the absence of information from the Spanish population, utility values were obtained from a British study that was based on the EQ-5D and time trade-off rates 25.

The external validation of the model was carried out by estimating the percentage of patients who progressed to cirrhosis starting from a population composition similar to that of the treated patients. Due to the different progression by sex incorporated in the model 2, this parameter was calculated separately for men and women. In addition, life expectancy was calculated in several stages of chronic liver disease, the mortality rate due to hepatic causes (advanced liver disease, liver transplantation and/or related liver mortality) and the mortality rate due to causes other than liver disease in a theoretical cohort of patients aged 49 years.

RESULTS

The study population included 656 patients with chronic hepatitis C infection and treated in Navarre between April 1, 2015 and December 31, 2016. Among those patients, 78% were 40 to 59 years old, and 68% were men; 68% of the patients had genotype 1 infection, 20% had HIV co-infection, 30% had fibrosis stage 0 to 1, 29% had fibrosis stage 2 to 3, and 38% had a diagnosis of cirrhosis without a history of decompensation (Table 1).

Table 1 Characteristics, treatment costs and sustained virological response of the cohort of patients treated for hepatitis C virus infection in Navarre

F0-F4: fibrosis stages 0 to 4. *Percentage calculated from the number of patients in each stage of the disease.

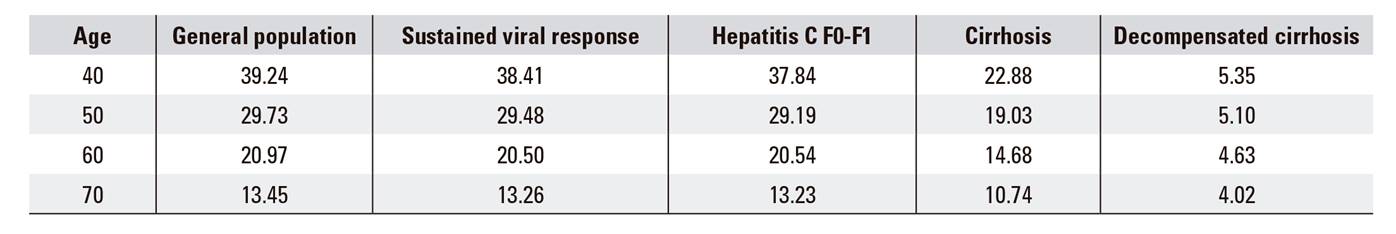

The validation results showed that, since the time of diagnosis, 10% and 15% of women progressed to cirrhosis in the first 20 and 30 years, respectively, compared to 13% and 16% of men. Life expectancy validation decreased as chronic liver disease progressed (Table 2). In the early stages, the deaths were mainly due to causes other than liver disease, while liver complications gained relevance in decompensated cirrhosis.

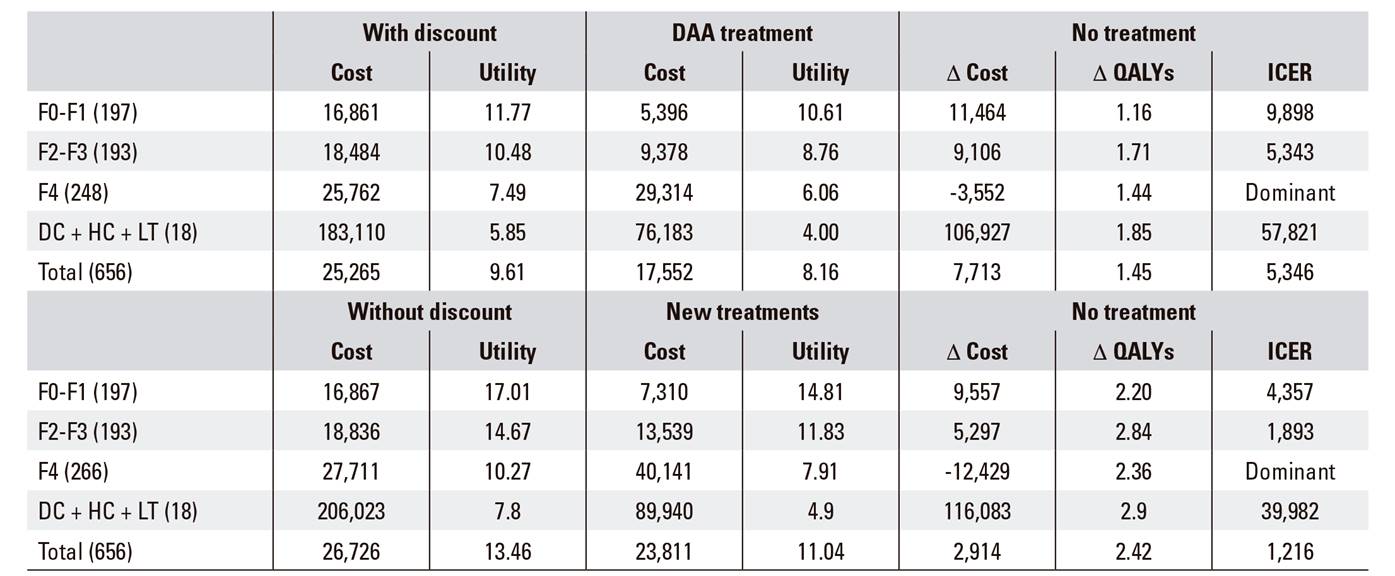

The average incremental cost-effectiveness (ICER) ratio with a discount for the whole cohort was 5,346 euros / QALY, being more efficient as the level of fibrosis increased, until reaching levels of dominance in fibrosis stage 4 (Table 3). The ICER was notably higher in the group with decompensated cirrhosis and hepatocarcinoma pending transplantation, reaching 57,821 euros / QALY. The ICER estimates in the probabilistic model were in the quadrant of the cost-effectiveness plane with positive incremental costs and effectiveness, and all the ICERs moved in the same direction, i.e., much lower than the efficiency threshold of 20,000 euros / QALY (Fig. 2). The result without discount was along the same line, although the lower incremental costs indicated that the costs savings from avoided advanced liver disease could be expected in the long term (Table 3).

Fig. 2 Probabilistic sensitivity analysis. Cost-effectiveness plane comparing the strategy of treatment versus no treatment (QALYs: quality adjusted life years).

Table 3 Cost-effectiveness analysis with and without discount of the application of the national hepatitis C strategy in Navarre

DAA: direct acting antivirals; QALYs: quality adjusted life years; ICER: incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; F0-F4: fibrosis stages 0 to 4; DC: decompensated cirrhosis; HC: hepatocarcinoma; LT: liver transplant.

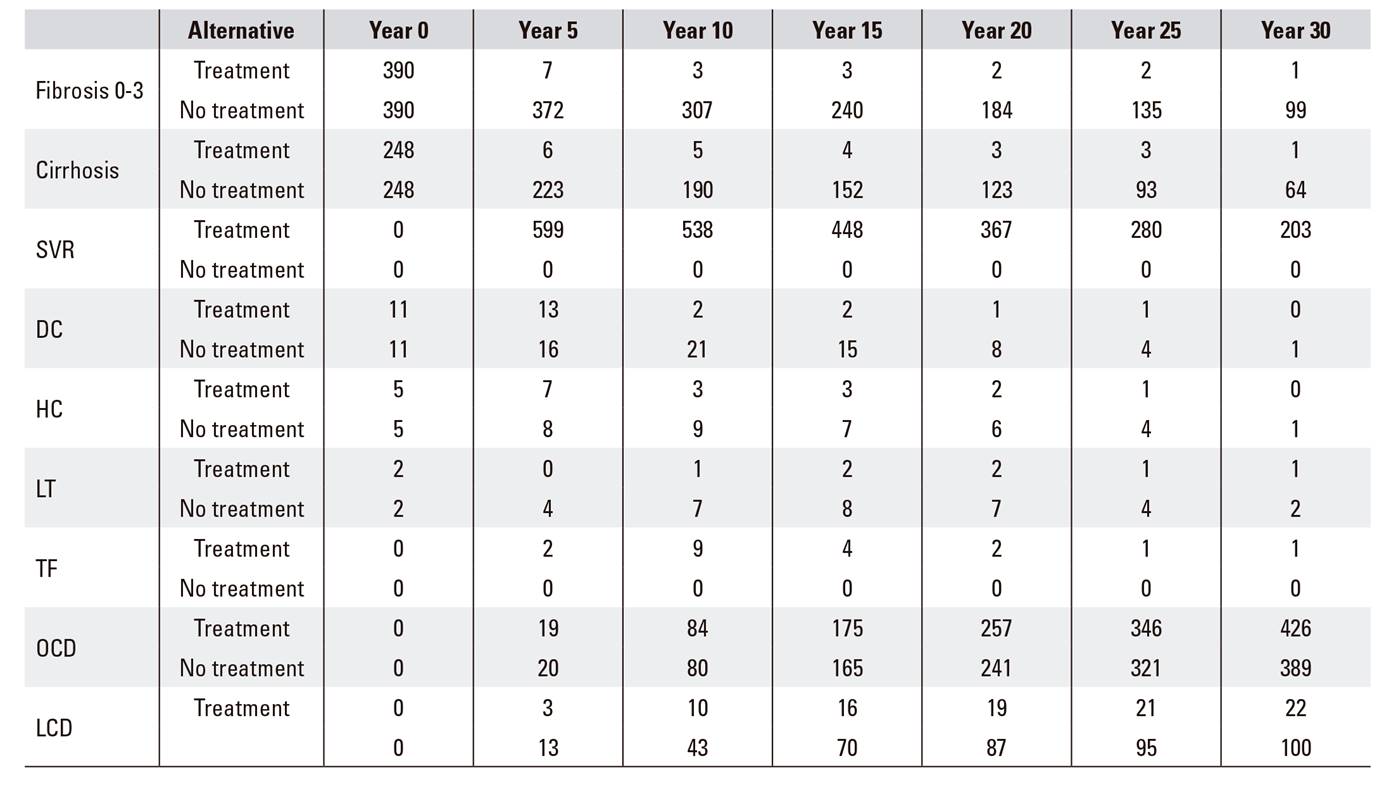

The epidemiological impact (Table 4) and the budgetary impact (Fig. 3) were calculated with a population approach. The total cost of the treatments in the study period was 13 million euros. The costs associated with chronic liver disease diminished as the benefit of the treatment was apparent and, consequently, increased the savings due to the avoided cases of decompensated cirrhosis, hepatocarcinoma and liver transplantation. Table 4 shows the five-year evolution in each stage of chronic liver disease in the 656 patients, according to the applied alternative. The number of patients dying at 30 years of age due to liver disease went from 100 in the non-treatment alternative to 22 in the treatment option, and the total number of deaths decreased from 489 to 448. The number of patients in cirrhosis dropped markedly with treatment.

Table 4 Epidemiological impact of the application of the national hepatitis C strategy in Navarre. Evolution of the number of individuals per stage and treatment option

SVR: sustained virological response; DC: decompensated cirrhosis; HC: hepatocarcinoma; LT: liver transplant; TF: transplant free of hepatitis C virus; OCD: death due to causes other than liver complications; LCD: death due to liver complications.

DISCUSSION

The application of the Strategic Plan during its first two years has been a cost-effective intervention, with an ICER well below the threshold of acceptability for our healthcare environment. This result is due to the compensation of the cost of treatment owing to avoided consumption of health resources in the medium and long terms that, in turn, is due to the reduction of events related to the complications of advanced liver disease. Although the Spanish health authorities have never defined a reference figure or a methodology to support a threshold of willingness to pay in economic evaluations, an ICER of 5,400 euros / QALY is considered very efficient. According to a review of the literature, the threshold of 30,000 euros / QALY proposed by Sacristán et al. in 2002 has been used for years 27. Recently, Vallejo-Torres et al. have updated this figure by taking into account the health expenditure of the different Spanish regions, and they estimated it between 22,000 and 25,000 euros / QALY 10. Our work showed an ICER much more favorable than in previous analyses estimated from the results of clinical trials 2,11,12,18, which is explained by the reduction in the cost of DAAs and the use of the absence of active treatment as reference. Both the analysis of the whole sample and that of patients with fibrosis stages 0 to 3 showed a result below the threshold. Moreover, it is noteworthy that the treatment of patients with fibrosis stage 4 was dominant. The concept of dominance in economic evaluation implies that the intervention or decision under evaluation must be adopted, because it improves the health outcomes measured in QALYs and saves costs 16,20. In contrast, in patients pending transplantation due to decompensated cirrhosis and hepatocarcinoma, the ICER is above the threshold. The reason for this lack of treatment efficiency is that in untreated patients, the costs of transplantation are saved when patients die before receiving the transplant. When the new DAAs appeared, those patients on waiting lists for transplant were given priority for treatment precisely because of that high risk of death.

The two determining parameters in the cost-effectiveness models of hepatitis C treatment were the percentage of SVR and the cost of treatment 28. The effectiveness of treatments to close to 100% in real-life data has been decisive for the reduction of the ICER. The cost of the first combinations of interferon-free DAAs reached 100,000 euros in the initial phases of market access, such as the 24-week regimen with sofosbuvir and simeprevir 2. However, the cost of drugs has been much lower in recent years as a result of negotiations for public financing of these treatments within the SPCHC. On the other hand, the low ICER is conditioned on the use of the "no treatment" option as a comparator. The "population view" of large-scale treatment developed by the SPCHC did not include a treatment based on peg-interferon and ribavirin for two reasons: in patients with advanced fibrosis the use of interferon would be contraindicated, and treatment of patients with a low stage of fibrosis was rejected because of partial efficacy and significant adverse reactions. Our results are consistent with those of the study by Turnés et al. that analyzed the economic and health impact of the first year of application of the SPCHC 29. However, because we used parameters from the real world instead of clinical trials in our study, the SVR was higher (98%). In addition, by using the actual price of medicines that decreased in price in the second year, the average cost per patient was lower.

From the viewpoint of follow-up costs, our estimates are conservative, since less intensive monitoring has been carried out for the second-generation DAAs, which has demonstrated good tolerance and safety 6,30. In our study, we considered a greater consumption of resources associated with medical and analytical consultations than that in current clinical practice. However, the initial phase of its therapeutic use was conditioned on the previous therapeutic management of peg-interferon and ribavirin, associated with boceprevir and telaprevir, which required close monitoring 3. Subsequently, the duration of the treatments was reduced, and the low incidence of adverse effects relaxed the follow-up of the therapy with the DAAs, which has rarely been associated with ribavirin.

The BIA allowed us to anticipate the financial stream needed to address the cost of hepatitis C treatment in Navarre. The balance began to be positive with a net savings from the third year 31. The total cost of treatment of the 645 patients was 12.1 million euros; that sum would prevent the evolution to advanced stages of chronic liver disease, which would reduce the total number of deaths by 30 years 32. The peak cost in the sixth year would be due to the necessary transplants in patients treated in the states of decompensated cirrhosis or hepatocarcinoma.

Most studies of economic evaluation of the treatment of hepatitis C have been based on Markov models that model natural history in patient cohorts 33. In this study, we used the discrete event simulation model, which incorporates individually the characteristics of patients 15,17,33 and exactly reproduces the cohort treated and the time of treatment. Two cohorts have been modeled, one in year 1 and another in year 2, with a multi-cohort approach that is not possible with Markov models 15,17,33.

The analysis of the differences of the ICER according to the stage of the patient's condition at the time of treatment supports the decision to prioritize patients at higher vital risk, as already considered by the SPCHC 8. The explanation of the efficiency gradient as the stage of fibrosis advances is due to the fact that in the early stages the probability of reaching the final stage of chronic liver disease is lower, because death may occur earlier due to other competitive causes. The treatment of patients with cirrhosis has an increased impact on rates of survival, since it decreases the probability of death due to hepatic disease, which in these patients is especially high. The result is a situation of dominance, with a negative incremental cost and a positive incremental effectiveness 16,20.

One limitation of the study is the use of health-related quality of life values from a study conducted in the United Kingdom. This study was used because of the lack of measurement studies of utilities carried out in Spain 25.

In conclusion, the implementation of the SPCHC is cost-effective, with an ICER well below the threshold of acceptability, since the cost of treatment is largely offset by savings in long-term health expenditure. The budgetary impact anticipated a net saving from the third year on. The two determining parameters were the decrease in the price of the treatment and the SVR close to 100% in the patients treated.

REFERENCES

1. Razavi H, Waked I, Sarrazin C, et al. The present and future disease burden of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection with today's treatment paradigm. J Viral Hepat 2014;21(Suppl. 1):34-59. DOI: 10.1016/S0168-8278(14)61324-6 [ Links ]

2. San Miguel R, Gimeno-Ballester V, Blázquez A, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of sofosbuvir-based regimens for chronic hepatitis C. Gut 2015;64:1277-88. DOI: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307772 [ Links ]

3. Fried MW. Side effects of therapy of hepatitis C and their management. Hepatology 2002;36(5 Suppl. 1):S237-44. DOI: 10.1053/jhep.2002.36810 [ Links ]

4. McHutchison JG, Ware JE Jr, Bayliss MS, et al; Hepatitis Interventional Therapy Group. The effects of interferon alpha-2b in combination with ribavirin on health related quality of life and work productivity. J Hepatol 2001;34(1):140-7. DOI: 10.1016/S0168-8278(00)00026-X [ Links ]

5. Blázquez-Pérez A, San Miguel R, Mar J. Cost-effectiveness analysis of triple therapy with protease inhibitors in treatment-naive hepatitis C patients. PharmacoEconomics 2013;31:919-31. DOI: 10.1007/s40273-013-0080-3 [ Links ]

6. Hézode C, Fontaine H, Dorival C, et al. Effectiveness of telaprevir or boceprevir in treatment-experienced patients with HCV genotype 1 infection and cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2014;147:132-142.e4. [ Links ]

7. Lawitz E, Mangia A, Wyles D, et al. Sofosbuvir for Previously Untreated Chronic Hepatitis C Infection. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1878-87. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214853 [ Links ]

8. Secretaría General de Sanidad y Consumo. Plan estratégico para el abordaje de la hepatitis C en el sistema nacional de salud. Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales y Consumo; 2015. Disponible en: https://www.msssi.gob.es/ciudadanos/enfLesiones/enfTransmisibles/docs/plan_estrategico_hepatitis_C.pdf Acceso 01/03/2018. [ Links ]

9. Sullivan SD, Mauskopf JA, Augustovski F, et al. Budget impact analysis-principles of good practice: report of the ISPOR 2012 Budget Impact Analysis Good Practice II Task Force. Value Health 2014;17(1):5-1. DOI: 10.1016/j.jval.2013.08.2291 [ Links ]

10. Vallejo-Torres L, García-Lorenzo B, Castilla I, et al. On the Estimation of the Cost-Effectiveness Threshold: Why, What, How? Value Health 2016;19:558-66. [ Links ]

11. Gimeno-Ballester V, Mar J, O'Leary A, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of therapeutic options for chronic hepatitis C genotype 3 infected patients. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;11(1):85-93. DOI: 10.1080/17474124.2016.1222271 [ Links ]

12. Mar J, Mar-Barrutia L, Gimeno-Ballester V, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of sofosbuvir-simeprevir regimens for chronic hepatitis C genotype 1 patients with advanced fibrosis.Med Clin (Barc) 2016;146(2):61-4. DOI: 10.1016/j.medcle.2015.09.005 [ Links ]

13. Garrison LP Jr, Neumann PJ, Erickson P, et al. Using real-world data for coverage and payment decisions: the ISPOR Real-World Data Task Force report. Value Health 2007;10(5):326-35. DOI: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00186.x [ Links ]

14. Aguinaga A, Díaz-González J, Pérez-García A, et al. The prevalence of diagnosed and undiagnosed hepatitis C virus infection in Navarra, Spain, 2014-2016. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin 2017. DOI: 10.1016/j.eimc.2016.12.008 [ Links ]

15. Karnon J, Stahl J, Brennan A, et al. Modeling using discrete event simulation: a report of the ISPOR-SMDM Modeling Good Research Practices Task Force-4. Med Decis Making 2012;32:701-11. DOI: 10.1177/0272989X12455462 [ Links ]

16. López-Bastida J, Oliva J, Antoñanzas F, et al. Spanish recommendations on economic evaluation of health technologies. Eur J Health Econ 2010;11(5):513-20. DOI: 10.1007/s10198-010-0244-4 [ Links ]

17. Arrospide A, Rue M, van Ravesteyn NT, et al. Economic evaluation of the breast cancer screening programme in the Basque Country: retrospective cost-effectiveness and budget impact analysis. BMC Cancer 2016;16:344. DOI: 10.1186/s12885-016-2386-y [ Links ]

18. Younossi ZM, Park H, Saab S, et al. Cost-effectiveness of all-oral ledipasvir/sofosbuvir regimens in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015;41:544-63. DOI: 10.1111/apt.13081 [ Links ]

19. Mar J, Martínez-Baz I, Ibarrondo O, et al. Survival and clinical events related to end-stage liver disease associated with HCV prior to the era of all oral direct-acting antiviral treatments. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;0:1-10. DOI: 10.1080/17474124.2017.1383155 [ Links ]

20. Mar J, Antoñanzas F, Pradas R, et al. Los modelos de Markov probabilísticos en la evaluación económica de tecnologías sanitarias: una guía práctica. Gac Sanit 2010;24:209-14. DOI: 10.1016/j.gaceta.2010.02.006 [ Links ]

21. Sawinski D, Forde KA, Locke JE, et al. Race but not Hepatitis C co-infection affects survival of HIV+ individuals on dialysis in contemporary practice. Kidney Int 2018;93(3):706-15. DOI: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.08.015 [ Links ]

22. Román R, Comas M, Hoffmeister L, et al. Determining the lifetime density function using a continuous approach. J Epidemiol Community Health 2007;61(10):923-5. [ Links ]

23. Liu S, Cipriano LE, Holodniy M, et al. New protease inhibitors for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Ann Intern Med 2012;156:279-90. DOI: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-4-201202210-00005 [ Links ]

24. RESOLUCIÓN 626/2014, de 5 de junio, del Director Gerente del Servicio Navarro de Salud-Osasunbidea, por la que se actualizan las tarifas por los servicios prestados por el Servicio Navarro de Salud-Osasunbidea. 2014. Disponible en: https://www.navarra.es/home_es/Actualidad/BON/Boletines/2014/133/ [Acceso 01/03/2018]. [ Links ]

25. Grieve R, Roberts J, Wright M, et al. Cost effectiveness of interferon alpha or peginterferon alpha with ribavirin for histologically mild chronic hepatitis C. Gut 2006;55(9):1332-8. DOI: 10.1136/gut.2005.064774 [ Links ]

26. Salomon JA, Weinstein MC, Hammitt JK, et al. Empirically calibrated model of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States. Am J Epidemiol 2002;156:761-73. DOI: 10.1093/aje/kwf100 [ Links ]

27. Sacristán JA, Oliva J, Del-Llano J, et al. ¿Qué es una tecnología sanitaria eficiente en España? Gac Sanit 2002;16:334-43 [ Links ]

28. Chhatwal J, He T, Lopez-Olivo MA. Systematic Review of Modelling Approaches for the Cost Effectiveness of Hepatitis C Treatment with Direct-Acting Antivirals. Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34(6):551-67. DOI: 10.1007/s40273-015-0373-9 [ Links ]

29. Turnes J, Domínguez Hernández R, Casado MA. Value and innovation of direct-acting antivirals: Long-term health outcomes of the strategic plan for management of hepatitis C in Spain. Rev Esp Enferm 2017;109(12):809-17. DOI: 10.17235/reed.2017.5063/2017 [ Links ]

30. Juanbeltz R, Goñi Esarte S, Úriz-Otano JI, et al. Safety of oral direct acting antiviral regimens for chronic hepatitis C in real life conditions. Postgrad Med 2017;129(4):476-483. DOI: 10.1080/00325481.2017.1311197 [ Links ]

31. Brosa M, Gisbert R, Rodríguez Barrios JM, et al. Principios, métodos, y aplicaciones del análisis del impacto presupuestario en sanidad. Pharmacoecon Spanish Res Artic 2005;2:65-79. DOI: 10.1007/BF03320900 [ Links ]

32. Fattovich G, Giustina G, Degos F, et al. Morbidity and mortality in compensated cirrhosis type C: a retrospective follow-up study of 384 patients. Gastroenterology 1997;112:463-72. DOI: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.pm9024300 [ Links ]

33. Stahl JE. Modelling methods for pharmacoeconomics and health technology assessment: an overview and guide. Pharmacoeconomics 2008;26(2):131-48. DOI: 10.2165/00019053-200826020-00004 [ Links ]

SOURCES OF FUNDING This work is part of the EIPT-VHC study, funded by an unrestricted grant from the National Strategic Plan of Hepatitis C of the Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality through CIBER of Epidemiology and Public Health of the Carlos III Health Institute. It has also been funded in part by the Carlos III Health Institute with the European Regional Development Fund (CM15/00119, CM17/00095 and INT17/00066).

Received: March 22, 2018; Accepted: April 17, 2018

text in

text in