Introduction

The armamentarium available for treating the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) is increasingly larger and more effective; said population presents overall survival rates very superior to those recorded in previous years1,2.

This increase in life expectancy entails, logically, an increase in comorbidities: those inherent to age and those that might be associated with the infection3,4. Currently, the management of this concomitant medication represents a challenge for clinicians at the time of initiating an antiretroviral treatment (ART) free of pharmacological interactions1,5,6 . This new patient, multi-pathological and polymedicated, demands a multidisciplinary approach, and the Hospital Pharmacy becomes a key agent in the task to prevent as much as possible any drug-related problem (DRP)7.

In our HIV patient consultations, intervention strategies have been historically focused on patient information and the improvement in treatment adherence. Now, we must also face the challenge of an aging population and the management of concomitant treatments and their potential interactions, that might compromise the safety and/or efficacy of ARTs as well as of the rest of treatments8,9.

The objective of this study is to understand, in real clinical practice, the frequency of potential pharmacological interactions in our patient cohort, and to identify those drugs most frequently involved, as well as their mechanisms and potential consequences. Obviously, this will help us to prevent them.

Methods

Design. A descriptive, retrospective study in a cohort of > 50-year-old patients on ART. The article has been prepared following the recommendations in the STROBE guidelines, available in: http://www.strobe-statement.org.

Study setting, population and period of time. Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena de Sevilla ( HUVM), a tertiary hospital with 800 beds and an assigned population as regional hospital of referral of 657,759 inhabitants.

Among other patients, 1,000 patients with HIV infection are seen per year at the external outpatient units, from Monday to Friday in the morning, and Mondays and Thursdays in the afternoon. There is one Pharmacy Technician and 1.5 Pharmacists in these units.

All > 50-year-old patients on ART were included, who had visited said units between January and December, 2014.

Sources of information. The Computer System by the Andalusian Public Health System, Diraya®, was used in order to identify home treatment, as support for the electronic clinical record and the application for outpatient dispensing by Farmatools®. In order to identify interactions, we used DRUGS. COM (www.drugs.com)10, an on-line database of information on medications, feeding off four independent providers (WoltersKluwerHealth, American Society of Health-System Pharmacist, Cerner Multum and Micromedex), and the product specifications available at https://www.aemps.gob.es.

Study variables and data collection. The variables collected were: age, gender, home treatment, ART and potential pharmacological interactions. The classification by Drugs.com was used, selecting those Moderate and Severe. Finally we analyzed the number, type and mechanism of action of interactions, as well as their potential effects described in the sources of information.

For this study, those patients with five or more molecules as outpatient prescriptions were considered “polymedicated” patients.

Statistical analysis. A descriptive analysis using the statistical package SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, version 18.0, with absolute and relative frequency used in order to describe the qualitative variables and the median, and the interquartile range for quantitative variables.

A univariate analysis was conducted in order to determine the association between the presence of potential pharmacological interactions and polymedication. For this objective, Square-chi test was used for the comparison of qualitative variables (Fisher’s Exact test in case of non-parametric variables), with statistically significant differences when p-value was < 0.05.

Ethical considerations. The collection of retrospective data from the Clinical Record for research purposes was conducted by the investigators, who were also in charge of data anonymization. The Research Ethics Committee was requested to approve the study protocol, as well as the exemption for obtaining informed consent, as stated in current legislation (SAS Order 3470/2009 of December, 16th, and BOE 310, of December, 25th, 2009).

Results

The study included 242 patients; 189 (78%) were male. Their median age (interquartile range) was of 57.5 (54-62) years. The number of patients with home treatment was 148 (61.2%), and 117 were polymedicated (48.3% of the total number). There was a considerably higher frequency of pharmacological interactions in polymedicated patients vs. non-polymedicated patients: 81.2% vs. 18.8% (p < 0.005). Table 1 describes the ARTs used in our patient cohort.

Table 1 Active antiretroviral agents (593) in our cohort (N = 242 patients)

*Ritonavir: 112 (18.9%).

Of the 243 potential interactions detected, 197 were considered moderate and 46 were severe, affecting 110 patients with the following distribution: 2 patients presented 7 potential interactions; 2 with 6; 3 with 5; 13 with 4; 18 with 3; 24 with 2, and 48 patients with one interaction. Thirty-four (34) patients (14% of the total number of patients) presented potentially severe interactions, with 46 interactions in total.

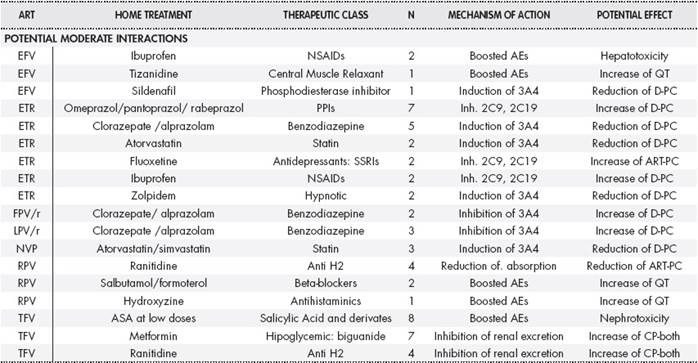

Table 2 and Table 2cont describes the interactions detected according to severity, antiretroviral drug, home medication, therapeutic group, interaction mechanisms, and their potential effects.

Table 2 Description of the potential interactions detected according to severity, antiretroviral drug, concomitant medication and therapeutic class, interaction mechanisms and potential effects

Table 2 (cont.) . Description of the potential interactions detected according to severity, antiretroviral drug, concomitant medication and therapeutic class, interaction mechanisms and potential effects

PPIs: Proton Pump Inhibitors. SSRIs: Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors. NSAIDs: Non-steroid antiinflammatories. ARBs: Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers. ACE inhibitors: Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors. AEs: Adverse Effects. Inh: Inhibition of and the relevant subsequent P450 cytochrome (or the relevant enzyme). Ind: Induction of and the relevant subsequent P450 cytochrome (or the relevant enzyme). Increase of D-PC: Increase of the plasma concentration of the other drug. Reduction of D-PC: Reduction of the plasma concentration of the other drug. Increase of ART-PC: Increase of the plasma concentration of the antiretroviral. Reduction of ART-PC: Reduction of the plasma concentration of the antiretroviral. Increase of D-EF: Increase of the clinical efficacy of the other drug. Reduction of D-EF: Reduction of the clinical efficacy of the other drug. Increase of ART-EF: Increase of the clinical efficacy of the antiretroviral. Reduction of ART-EF: Reduction of the clinical efficacy of the antiretroviral. DOAC: Direct oral anticoagulant.

The ARTs most frequently involved were boosted PIs (49.3%), followed by NNRTIs (38.3%). Considering severe interactions only, boosted PIs were responsible for 76% of cases. Regarding home treatment, most interactions involved psychiatric medication (28.4%), followed by cardiovascular drugs (25.5%).

Regarding severe interactions, statins were the group of drugs with higher involvement (24%), followed by inhaled corticosteroids (15%).

Regarding the consequences of these interactions, the outcome in 48% of them was an increase in the plasma concentration / effect of outpatient medication, in 24.3% there was a reduction, while in only 7.2% there was an impact on ART levels. In 23.4% of them, this consequence translated into boosted adverse effects: we must highlight the risk of QT interval elevation and an increase in hypotensive effect with risk of falls.

Discussion

The median age (IQR) in our cohort of patients was 57.5 (54-62) years, and the majority were male (81.8%). These characteristics are similar to those described by Álvarez Martín et al.11. These authors included > 55-year-old patients, with a mean age of 60 years, and 78% of them were male. Over half of the patients were on some prescribed home treatment (61.2%), and in almost half of patients more than five different molecules were identified. In the study by Álvarez Martín et al.11 almost 70% of patients had some associated medication.

We must highlight the high percentage of patients who presented some type of potentially moderate/severe interaction (44.6%), similar to the findings by Álvarez Martín et al.11. In over half of patients, more than one interaction was identified, and there were even patients with seven simultaneous potential interactions.

In the review by Manzardo C et al.6, boosted PIs were the ARTs more frequently associated with severe interactions. Equally, Molas E et al.13 revealed that PIs were the group of drugs with higher interactions, with a 47% rate which is similar to the one in our cohort. And at the same time, in the study by Yiu P et al.12 , PIs were again the agents with more interactions present, both in young (44%) and in elderly patients (42%). In this study, these were followed by Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (NRTIs) and Non-nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (NNRTIs). In our case, however, there was a wide superiority of NNRTIs vs. NRTIs, 38.3 vs. 10.3% respectively.

Regarding outpatient treatments, outcomes were similar to ours both in the studies by Martín11 and in the study by Marzolini C14, given that psychiatric and cardiovascular medication presented the higher percentage of interactions. And this is also comparable with the study by Tseng A15 where cardio-vascular medication occupied the first place (37%).

We have detected a high frequency of interactions classified as severe in Drugs (18%); this rate is superior to the one described in other studies, and we must highlight the involvement of statins.

One of the main limitations in our study could be its retrospective nature; but given the fact that it is merely descriptive, it is not considered very relevant.

Finally, we must highlight that this knowledge of the drugs involved, as well as of the mechanisms of interactions and their potential effects, will allow us to design strategies targeted to an early detection of patient-medication groups at higher risk, and ultimately to an improvement in health outcomes.

Contribution to scientific literature

This article shows the clinical reality in our patients, and analyzes in detail an area of growing interest with limited scientific production. Given the aging in the HIV population, fortunately this is a matter that presents particular relevance: a better knowledge of pharmacological interactions and their potential effects will allow us to select and classify our patients / higher-risk medication, and anticipate strategies targeted to improving health outcomes. The importance of the Pharmacist role is also highlighted; through pharmacotherapeutical follow-up and due to their closeness and access to patients, they will play a key role from the Pharmacy Outpatient Units, beyond mere dispensing.

text in

text in