My SciELO

Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Enfermería Global

On-line version ISSN 1695-6141

Enferm. glob. vol.21 n.67 Murcia Jul. 2022 Epub Sep 19, 2022

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/eglobal.491001

Originals

Analysis of cases of sexual violence in school adolescents

1Federal University of Paraíba. Brazil

2Federal University of Piauí. Brazil

Methodology:

The investigation originated from a macro-project, transversal, descriptive and quantitative, carried out in public schools in the city of Picos, Piauí, Brazil, with schoolchildren aged 13 to 17 years. The collection of data takes place in 2018, through a self-completed questionnaire by the participants. From the sample of 1,051 adolescents, 38 questionnaires were evaluated who reported victimization for sexual violence at some point in their lives.

Results:

In the analysis of these cases of sexual violence, it was noticed that they are mainly perpetrated by an ex-boyfriend (13.2%) or friend (10.5%), with more than a third of the episodes occurring in childhood (49.9%), some still persist to the present day (5.3%). As for the sociodemographic profile, there was a prevalence of females (81.6%), brown (42.1%), aged 10 to 12 years at the time of the episode, residents with father and mother (44.7%), Catholic (60.5%) and with economic weakness (23.7%). Regarding sexual and reproductive aspects, heterosexuality (86.8%), lack of a steady boyfriend (65.8%), had consented sexual intercourse (55.3%), and used condoms at the time (36 .8%). Also, in relation to the violence suffered, the adolescents reported the awakening of negative feelings, such as: sadness and fear (50%), shame (44.7%) and anger (42.1%) after the episode(s).

Conclusion:

The theme is surrounded by cultural taboos and social prejudices. Therefore, it is expected that this study will contribute to the denunciation of cases, dissemination of knowledge and breaking these sociocultural precepts in civil society and the scientific community.

Keywords: Cross-sectional studies; Sex offenses; Adolescent

INTRODUCTION

According to the Statute of Children and Adolescents (ECA) (1990) an adolescent is considered to be one between the ages of 12 and 181. The World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Society for the Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect (ISPCAN) state that adolescents are more susceptible to sexual violence, since by the developmental stage they are unable to give consent to such a practice2.

Sexual violence comprises any type of sexual act and the actions that precede it, such as flirting, comments and caresses, being practiced by any person, as long as it is used with coercion3. Therefore, it is a problem that affects not only physical health but also mental health, which can cause temporary or permanent damage4. In this context, there are several actions that are characterized as sexual violence, not only restricted to rape itself, such as: verbal harassment, exposure to pornographic material, exhibitionism, voyeurism, sexual exploitation, touches, caresses, and physical contact with interfemoral intercourse, with or without penetration2.

Even though Brazil has been one of the pioneer countries in the construction of public policies aimed at combating sexual violence against children and adolescents, with landmarks such as the Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989), the enactment of the Child and Adolescent Statute (1990) and the approval of the National Plan to Combat Sexual Violence against Children and Adolescents (2000), cases of sexual violence against adolescents still persist in the daily life of Brazilian society1.

In this scenario, according to the Department of Informatics of the Unified Health System in Brazil (DATASUS), from 2010 to 2017, there were more than 90,000 compulsory reports of sexual violence against adolescents. The Southeast, North and South regions are responsible for the highest rates with 32.7%, 21.9% and 18.5%, respectively. There is also a higher prevalence of victims aged between 12 and 14 years (67.9%), with the victim's own residence as the main place of occurrence (58%)5.

Sexual violence is recognized as a public health problem and a violation of universal human rights, with high prevalence6. Still in this context, studies indicate that despite the large number of underreported cases and their increasing incidence, there is a difficulty in obtaining a number of cases that are really compatible with reality, since victims are too afraid to report the episode(s) due to the deep pact of silence, cultural taboos and, usually, proximity to the aggressor. This contributes to the lack of knowledge of its real incidence and mechanisms, thus making it difficult to capture cases by health, police, and justice services7.

In short, the proposed study aims to analyze cases of sexual violence among school adolescents, and it becomes relevant as the theme worked on is still considered a controversial issue for society, with deficient preventive strategies, in addition to the difficulty in identifying and handling these cases.

MATERIAL AND METHOD

This is a descriptive study with a cross-sectional design and a quantitative approach. This study is part of a broader research that was carried out with the adolescent population in 26 schools in the municipality of Picos, Piauí, 16 of which are administered by the state and 10 by the municipality.

To select these schools, the following inclusion criterion was followed, having more than 10 students enrolled in the age group from 13 to 17 years old. And as an exclusion criterion, having a high school education integrated into the vocational technical course and the Education for Youth and Adults (EJA) program. After that, we started to compose the sample by applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria of the participants.

In this context, in order for the sample to faithfully represent the population, a maximum sampling error of approximately 3% was calculated, in absolute values, and a confidence level of 99%. The calculation used to obtain the sample was the formula for cross-sectional studies with a finite population9, in which a sample of 1073 adolescents was obtained, 881 from state schools and 192 from municipal schools, in which the sample it was random by cluster for the selection of schools and census for the approach of the participants.

For the participants, the following inclusion criteria were considered: adolescents duly enrolled in regular state and municipal schools in the urban area of Picos, Piauí, in the morning and afternoon shifts; with the age group of 13 to 17 years. This age was chosen because it is similar to the one used in the 2015 National School Health Survey (PeNSE), which allowed for better comparisons with this and other studies8. Regarding the exclusion criteria, the following were followed: the student was not present in the classroom on the day the questionnaire was applied; the student has a disability or disorder that prevents him from answering the questionnaire alone.

In this way, it is noteworthy that the choice was made to select the school and not the adolescent to guarantee the anonymity of the participant, given that the subject addressed in this research (sexual and reproductive health) is still considered a taboo for society. Thus, data collection was carried out in the selected schools through self-completed questionnaires by adolescents who voluntarily agreed to participate in the study and which their parents previously released through the Informed Consent Term (ICF), with the student signing the Free Informed Assent Term (TALE) before completing the questionnaire.

It should also be noted that, before data collection, the researcher responsible for the macro-project trained Nursing students to apply the questionnaires in schools and then carried out the first visit to the selected schools to explain the importance of developing this study to the board and to teachers. At that moment, a new survey of the formation of classes of each school was carried out, and in a second visit to the schools, the research was presented to the students and the Free and Informed Consent Term (ICF) was delivered to those who wished to participate, took it to the parents to sign releasing their children's participation in the research, since the population is adolescents under 18 years of age.

Also on the second visit, the adolescents were asked to inform the telephone number of their parents or guardians and to authorize the researcher in charge to call them and explain about the research and the importance of the adolescents' participation, provided that the parents or guardians have authorized it. of the ICF. There was also a third visit, previously scheduled to collect the signed ICF. Thus, on the day of data collection, being the fourth visit to the schools, all adolescents present in the classes of the selected schools, duly authorized by their parents, were invited to answer the instrument.

The collected data were entered and tabulated in the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software, version 20.0 and their results were presented in Tables and graphs, using descriptive statistics.

In this perspective, it is worth mentioning that a total of 1,051 adolescents enrolled in state and municipal schools participated in the macro-project. However, only 38 adolescents who claimed to have suffered some types of sexual violence were included in this study. It is important to emphasize that the investigated adolescents did not always suffer violence at their current age, that is, they may have been victims during childhood.

To carry out this research, all ethical and legal principles proposed by Resolution No. 466/12, which governs research involving human beings, were respected. In addition, the project was submitted and approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of the Federal University of Piauí with the Opinion Report No. 2,429,523.

RESULTS

There is an assessment of 38 questionnaires whose participating adolescents said they had already suffered sexual violence.

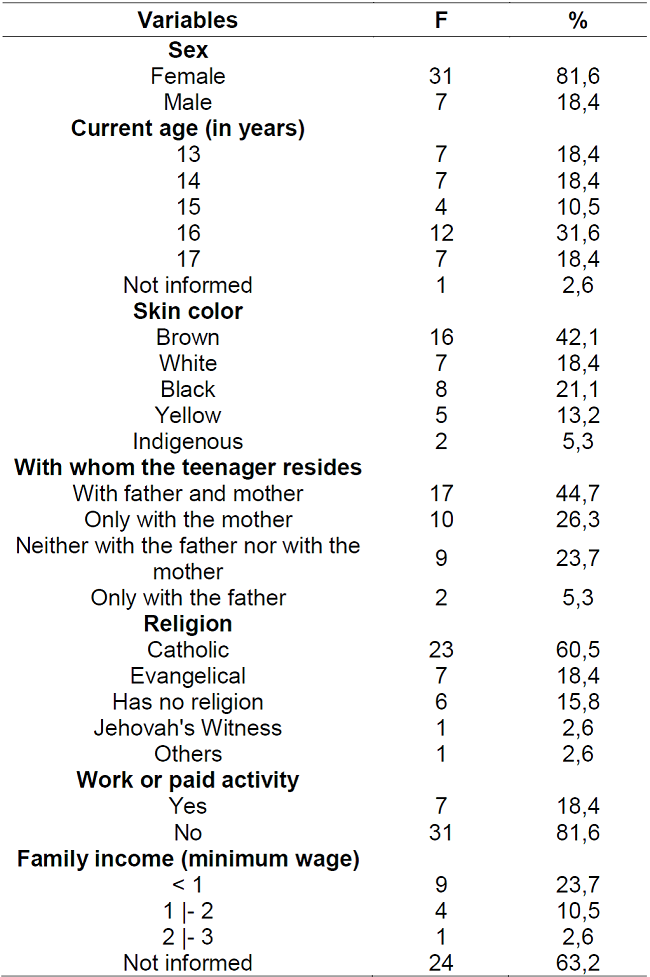

According toTable 1, female adolescents prevail (81.6%), aged 16 years (31.6%) and brown skin color as the most mentioned (42.1%). More than 1/3 of these adolescents live with their parents (44.7%), followed by 26.3% who only live with their mother. Approximately ¼ of adolescents have a family income of less than one minimum wage and more than half have Catholicism as their religion. Although a small percentage declares to work (18.4%), most of these adolescents stated that they do not have any paid activities (81.6%).

Table 1: Profile of the adolescents surveyed, according to sociodemographic and economic variables. Picos - Piauí, Brazil, 2020. n= 38

Source: Research data

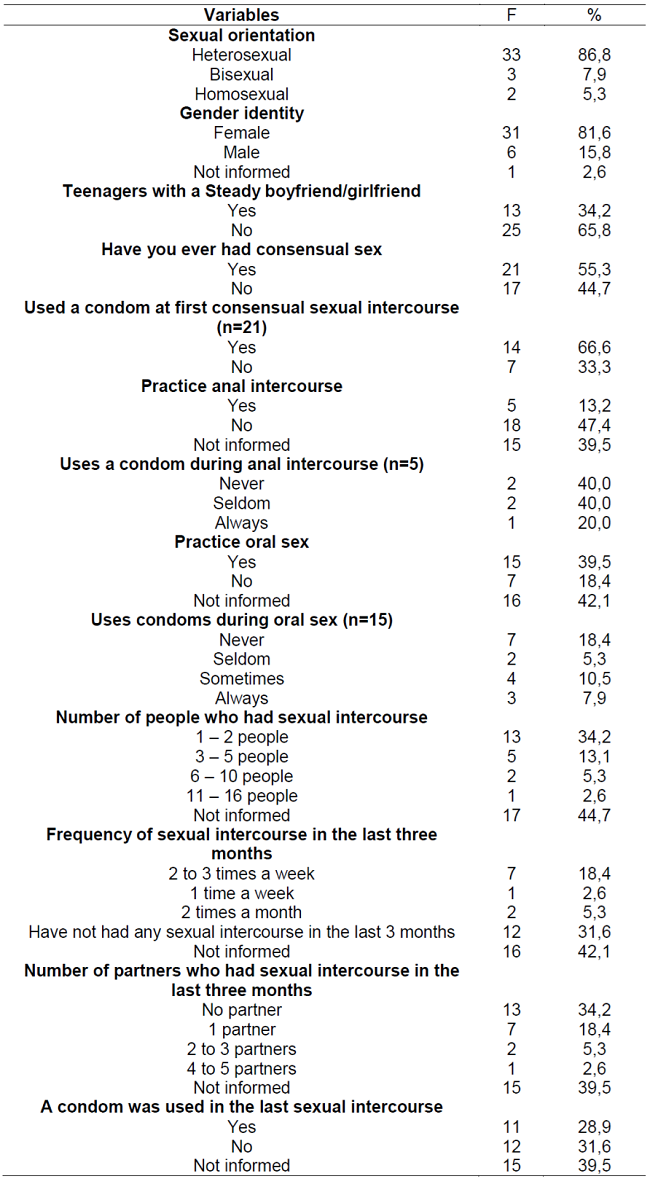

According toTable 2, about 86.8% of the adolescents are heterosexual, with female being the prevailing gender identity (81.6%). Most of them reported not having a steady boyfriend (65.8%). About 55.3% reported having already performed consensual sexual practice and 44.7% had not performed this practice consensually. Still in this context, it is observed that 66.6% of the adolescents claimed to have used condoms during this practice.

Table 2: Sexual and reproductive history of school adolescents. Picos - Piauí, Brazil, 2020. n= 38

Source: Research data

Of the adolescents surveyed, a relevant percentage does not usually practice anal sex (47.4%), but of those who use this practice (13.2%), a small portion reported that they never used condoms (5.3%). However, the majority preferred not to inform whether or not they use condoms during anal intercourse (86.8%). As for the practice of oral sex, more than1/3said they performed it (39.5%), with 18.4% without a condom. Furthermore, 34.2% of the adolescents said they had one to two sexual partners in their lifetime.

Regarding the prevalent findings in the last three months, adolescents reported having had no sexual partner (34.2%), followed by a sexual partner (18.4%). Also in this context, they claimed to have a frequency of sexual intercourse between 2 and 3 times a week (18.4%) and that in the last sexual intercourse 31.6% did not use a condom.

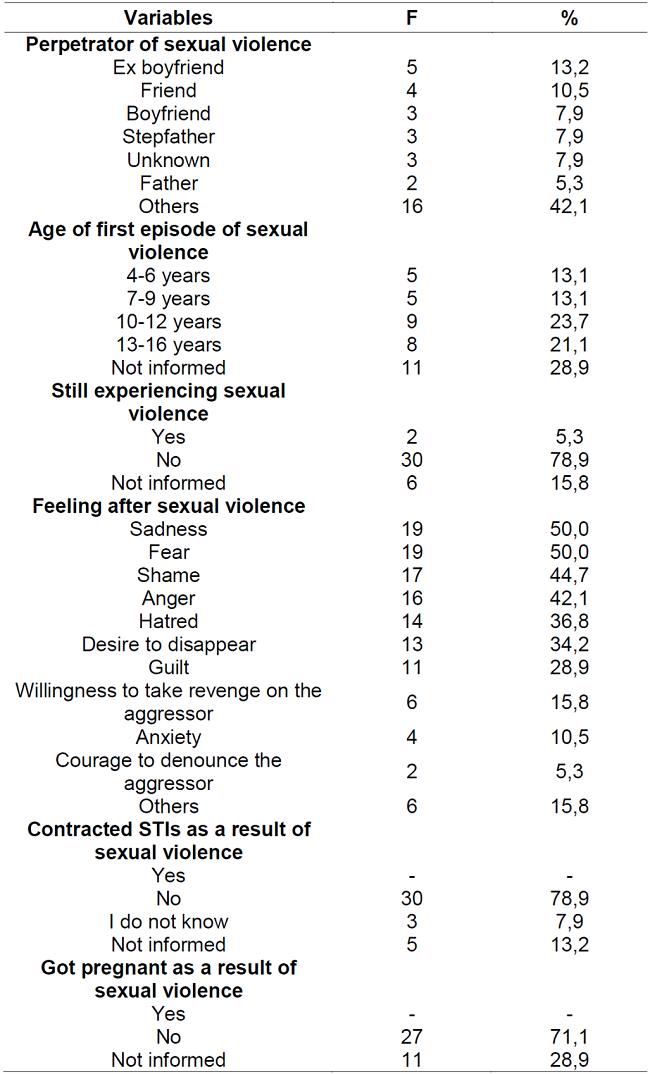

According toTable 3, it is observed that, among the perpetrators of the investigated sexual violence, the ex-boyfriend (13.2%) and the friend (10.5%) stand out, an act that prevails in victims who have from 10 to 12 years (23.7%). Among the feelings aroused after the episode(s) of sexual violence, half of the adolescents felt sadness and fear (50%), followed by shame (44.7) and anger (42.1%). Although most claim not to have become pregnant (71.1%) or to have contracted any STIs (78.9%) as a result of abuse, there are still those who do not know if they have contracted any STIs (7.9%) and those who still suffer sexual violence (5.3%).

Table 3: Characterization of sexual violence suffered by the adolescents surveyed. Picos - Piauí, Brazil, 2020. n= 38

Source: Research data

Table 4: Family Context of the surveyed adolescents. Picos - Piauí, Brazil, 2020. n= 38

Source: Research data

Regarding the last 30 days,1/3of the adolescents stated that their parents or guardians always know what they do with their time on a daily basis (31.6%), but they never check if they have done their homework. (50%), do not even touch their belongings without their permission (39.5%). Also in this event, about 44.7% reported that they did not miss a day of school without their parents' permission. Furthermore, 39.5% reported that parents never talk about sex.

DISCUSSION

It is known that sexual violence against adolescents is a serious public health problem, which often refers to events that occurred in childhood. Knowing that this type of violence is still underreported throughout the country, it is observed that according to DATASUS only in 2017 more than 130 cases of children (29.8%) and adolescents (70.1%) victims of sexual violence were reported5. When this problem considers larger populations, such as the capital of Amazonas, there is an exponentially greater number of cases, being the most reported form of violence among children and adolescents, corresponding to 135.3 cases per 100,000 and 194.2 cases/100 thousand respectively only in 201310.

In view of the data presented, it is understood that sexual violence against children and adolescents is present in different scenarios, and its mechanisms are not yet fully known. However, the search for the characterization of cases of sexual violence becomes the first step to subsidize policies capable of reducing the number of cases, enabling the identification of cases in a timely manner and possible forms of prevention10.

As for the characteristics of the victims, there is connivance with the literature regarding the prevalence of female victims, since an integrative literature review that analyzed the world scientific evidence about risk factors related to the exposure of adolescents to sexual violence, determined that female adolescents are more affected when compared to males, with rates of 8-31% and 3-17%, respectively11. In this scenario, a qualitative study that includes the theme of sexual violence, narrated from the point of view of adolescents, attributed this phenomenon as a consequence of the perpetuation of the sexist culture, degrading the female sex12.

The prevalence of self-declared brown victims in this study was understood as a regional characteristic, since it has this prevalent characteristic in common with a study based on the same theme carried out in Pernambuco, a state geographically neighboring Piauí13. And, in turn, it is contrasted when compared to a North American study that used sociodemographic data referring to approximately 657,719 thousand emergency room visits due to sexual violence and obtained white skin color as the most prevalent among the victims14.

A study carried out in Brazil found a high prevalence of victims of sexual violence who reported not living with their parents3. Thus, it is understood that adolescents who live with their father and mother, theoretically, have a sTable family nucleus, composed of blood and emotional relationships that should constitute a protective factor against the occurrence of sexual violence against children and adolescents. However, there are findings from studies stating that it is not uncommon for parents themselves to commit it, since they establish a relationship of power over the victim, preventing the process of breaking the silence and making it difficult to identify and report cases11. Thus, it is observed that, although this protective factor is present in the findings of this study, all adolescents who answered the instrument questionnaire of this study (n=38) at some point in their lives were victims of sexual violence.

Low family income is pointed out as one of the risk factors that predispose children and adolescents to suffer sexual violence11. This is a factor portrayed in the present study by highlighting that more than ¼ survive on less than one minimum wage per family. Thus, in an attempt to explain the large percentage of low-income adolescent victims of sexual abuse presented in this study, a research that examined the association between income inequality and intimate partner violence, through population surveys from several countries, determined a significant positive association15. Furthermore, studies claim that performing paid activities are important supporting factors in the lives of sexually abused people3,11. However, it is worth noting that the low family income found in this study is probably due to the fact that the research was carried out in a public school, where students, in most cases, belong to families with lower socioeconomic status.

Sexual violence, in any of its presentations, must be understood as a serious problem in the lives of all people, regardless of their sexual orientation. Thus, even though the findings of this study indicate a prevalence of heterosexual victims, the LGB population (lesbians, gays, and bisexuals), even if added together, represent a population minority, but it constitutes an important data, considering what was discussed in a Chinese study in which the LGB population minority has a greater tendency to develop mental and physical problems as a result of sexual violence when compared to the heterosexual population16. Still in this context, there is a scarcity of research on this topic that addresses the LGBT public and, mainly, Transsexuals17.

Still on the irregular use of condoms in sexual practices, it is supposed to be a prevalent behavior in adolescence, since studies point to failures in this public's knowledge about the protection and prevention of their sexual and reproductive health, evidenced by the absence of condom use as a means capable of preventing sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and unwanted pregnancies18,19.

Regarding the last three months, most of the adolescents studied said they did not have a steady boyfriend and had a frequency of sexual intercourse between two and three times a week. Considering that more than1/3preferred not to inform the number of sexual partners, therefore, these data were considered important and suggestive of casual sexual activities, characterizing one of the risk factors present in the occurrence of sexual violence among adolescents3.

Based on the above, it is estimated that the reproduction of social gender patterns, in the experiences of casual relationships, affects both sexes in different ways and contributes to the maintenance of hierarchies and inequalities, strengthening the silencing on the subject, making sexual violence invisible. before this way to relate, which may be related to the lack of knowledge of the compliance of the number of cases20.

While trying to characterize the victims of sexual violence, it is sought to know the relationship between victim and aggressor, it is identified that the main aggressors mentioned in the results of this work, such as the (ex) boyfriend, friend, and stepfather, corroborate with the findings of a systematic review carried out in Chile, which determined a high prevalence of aggressors as people known to the victim. These findings are even aligned through the aggressor's point of view, when reporting as common categories of victims: (ex) partners, friends, and acquaintances21. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that a Swedish study highlighted persuasion, intimidation and/or the use of social position as the main tools used by adults in the perpetration of sexual violence against children and adolescents22.

In this context, most studies establish a high probability that the aggressor is male, especially when there is an intimate relationship10,23as stated in a study carried out in Nigeria, in which men were twice as likely to commit sexual violence when compared to women24.

Corroborating the aforementioned data, it is known that intimate relationships can provide a means for the occurrence of sexual violence against adolescents, especially in females. Thus, a survey that used demographic and health data from Nepal, in order to study the prevalence of sexual violence and unintentional pregnancy and its association among married women aged 15 to 24 years, identified that about 22.7% of women already had an unwanted pregnancy and almost one in 10 women has experienced sexual violence from their husbands25. On the other hand, in the United States, the prevalence of known aggressors (24.8%) by the victim is lower than the percentage of unknown aggressors (37.5%), as stated in a retrospective study that considered the years 2005 to 201314.

According to a survey carried out in Manaus from 2009 to 2016, the role of males as the main perpetrator of sexual violence is reaffirmed, and it is inferred that victims aged between 10 and 14 years are prevalent (10). In addition, a cross-sectional study that used data from the National School Health Survey (PeNSE) conducted in 2015 determined that there is a high prevalence of sexual violence in schoolchildren under the age of 13 years3. Thus, the low schooling and age presented by these victims are understood as factors that contribute to the culture of silence in these cases of violence. In this sense, a study found that for each additional year of age, adolescents have approximately 9% lower chances of revealing the episode(s) of sexual violence, a fact that may be related to social factors and fear of moral judgments20,26

The data discussed in this research state that a minority of 5.3% of adolescents still suffer sexual abuse. This phenomenon can be explained due to the difficulty in breaking the chain of occurrence of these episodes, as it involves intimidation mechanisms that result in the victim's silence, being probably intensified by the social taboos involved in the theme and because they are discredited by the family or community. To cite, the reported in a study that, in the search to identify the limits of tolerance of women in the face of sexual abuse suffered in childhood, found that there were cases that happened in childhood and remain a secret from the family until today, about 36 years old12 27.

In relation to the emotional state of the victims, through a qualitative analysis, the main feelings aroused in these women, who experienced sexual violence as children, were listed: disgust, shame, anger, desire for revenge, hurt, worthlessness, disgust.27. In this sense, it is understood that there is an alignment between the findings in the literature and those presented in this study.

Bullies are likely to develop mental health problems, as intimate partner perpetration is strongly associated with the development of severe sadness and suicidal ideation in female perpetrators, and feelings of worthlessness and increased use of alcohol by male perpetrators24. While victims are constantly involved by negative feelings, clinically expressing symptoms related to depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress21.

Still in this context, another study pointed to an increased risk of suicidal ideation, attempts and death associated with the occurrence of sexual violence in childhood28. In addition, another study linked sexual violence victimization with personality disorders and intimate behavioral problems29. Thus, it is emphasized that sexual violence must be understood as a trauma that leads to complex and individual complications throughout the victims' lives21.

Still on the damage caused by this type of violence, even if adolescents claim not to have contracted an STI and/or become pregnant as a result of the episode(s), study findings express that these are common consequences involved in cases of sexual violence25.

In the family context, the adolescents reported a significant degree of disinterest on the part of parents or guardians in relation to the adolescents' school and routine activities. From this perspective, studies show a high rate of adolescents who suffered sexual violence and who did not have their activities constantly supervised by the family or guardians3.

In this context, the family and the school are defended as protective factors against the occurrence of sexual violence against children and adolescents12. This scenario has the potential to favor interdisciplinary professional action in health, guided by nursing, in order to make it possible to meet health education and face the vulnerabilities that permeate the full development of children and adolescents13.

Given the strong influence of sexual violence on people's lives, effective strategies are suggested to face this problem and prevent it. Thus, a strategy is highlighted, carried out through an action research on the islands of Trinidad and Tobago, which, by counting on a media campaign added to community efforts to break the silence of the victims, it was possible to promote new guidelines of good practices to service providers, of culturally relevant and context-sensitive, adapTable and implemenTable content, and allowed a continuous multidisciplinary response to the complications resulting from this violence, even modifying public policies, in order to support victims and enable better knowledge of the cases30.

In addition to the above, a study carried out in the capital of Pernambuco evaluated the media as a relevant influencing tool in breaking the silence, a behavior constantly adopted by victims of sexual violence. This medium has the potential to enable similar strategies throughout Brazil12. Thus, it is expected that the data can support public policies aimed at the reported aggravation, emphasizing the importance of promoting other studies to improve the understanding of the complexity of the mechanisms that encompass sexual violence against children and adolescents.

CONCLUSIONS

The investigation of the factors involved in sexual violence suffered by adolescents allowed a glimpse of the scenario in which this violence takes place, enabling the understanding of sociodemographic, relational, behavioral, and sentimental aspects corresponding to the proposed objectives.

Among the main difficulties of this study, we highlight the taboo involved by the theme, which often inhibits the participation of adolescents, permission from the family and/or non-collaboration on the part of teachers and principals; the extensive conFiguration of the adapted questionnaire; the large number of participating adolescents; in addition to the geographic barriers to access to schools, even though they are only schools in the urban area. The probable underreporting of cases is also highlighted, considering that of the 1073 adolescents evaluated, only 38 reported having suffered some type of sexual violence at some point in their lives, which also demonstrates an important difficulty in discussing the subject.

The present work was limited to descriptive factors, making tests and statistical associations impossible, given the discrepancy between the population that claimed to have already suffered sexual violence and the one that denied experiencing it. In addition, memory bias may or may not be present in the findings and the fact that the research was carried out only in public schools, does not allow a real identification of students from all economic classes.

Among the main contributions, there is the approach to the theme, as it is still an area little addressed and consequently minimally disseminated in civil society and can be considered a sociocultural taboo perpetuated in time.

Other contributions are related to the knowledge produced by the scientific community and the contribution to the understanding of the factors that surround child sexual violence. Thus, studies are suggested that specifically address both the mechanisms of occurrence of the episode(s), explaining them and the impacts suffered by adolescents as a result of sexual violence.

REFERENCIAS

1. Brasil. Lei n° 8.069, de 13 de julho de 1990. Estatuto da Criança e do adolescente. Diário oficial da União. Julho de 1990. Disponível em:http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l8069.htm [ Links ]

2. Hohendorff JV, Patias, ND. Violência sexual contra crianças e adolescentes: identificação, consequências e indicações de manejo. Barbarói [Internet]. 2017; 49: 239-257. Disponível em:https://online.unisc.br/seer/index.php/barbaroi/article/view/9474 [ Links ]

3. Santos MJ, Mascarenhas MDM, Malta DC, Lima CM, Silva MMA. Prevalência de violência sexual e fatores associados entre estudantes do ensino fundamental -Brasil, 2015. Ciênc. saúde coletiva [Internet]. 2019; 24(2): 535-544. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232018242.13112017 [ Links ]

4. Silva LMP, Sousa TDA, Cardoso MD, Souza LFS, Santos TMB. Violência perpetrada contra crianças e adolescentes. Rev. enferm. UFPE on line [Internet]. 2018; 12(6): 1696-1704. Disponível em: https://periodicos.ufpe.br/revistas/revistaenfermagem/article/view/23153/29215 [ Links ]

5. DATASUS. Ministério da Saúde. Departamento de Informática do Sistema Único de Saúde. Epidemiológicas e morbidades. Brasília, DF: Ministério da Saúde, 2019. [ Links ]

6. Delziovo CR, Bolsono CC, Nazário NO, Coelho EBS. Características dos casos de violência sexual contra mulheres adolescentes e adultas notificados pelos serviços públicos de saúde em Santa Catarina, Brasil. Cad saúde pública [Internet]. 2017; 33(6): e00002716. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311x00002716 [ Links ]

7. Batista VC, Back IR, Monteschio LVC, Arruda DC, Rickli HC, Grespan LR, et al. Perfil das notificações sobre violência sexual. Rev. enferm. UFPE on line [Internet]. 2018; 12(5): 1372-1380. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.5205/1981-8963-v12i5a234546p1372-1380-2018 [ Links ]

8. Brasil. Ministério do Planejamento, Desenvolvimento e Gestão, Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística-IBGE, Coordenação de População e Indicadores Sociais. Pesquisa nacional de saúde do escolar: 2015 / IBGE. Ministério da Saúde, Rio de Janeiro, 2016. Disponível em: https://www.unicef.org/brazil/pt/br_cadernoBR_SOWCR11(3).pdf [ Links ]

9. Miot HA. Tamanho da amostra em estudos clínicos e experimentais. J Vasc Bras [Internet]. 2011; 10(6): 275-278. Disponível em: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1677-54492011000400001 [ Links ]

10. Oliveira NF, Moraes CL, Junger WL, Reichenheim ME. Violência contra crianças e adolescentes em Manaus, Amazonas: estudo descritivo dos casos e análise da completude das fichas de notificação, 2009-2016. Epidemiol. Serv. Saúde [Internet]. 2020; 29(1): e2018438. Disponível em: http://dx.doi.org/10.5123/s1679-49742020000100012 [ Links ]

11. Souza VP, Gusmão TLA, Neto WB, Guedes TG, Monteiro EMLM. Fatores de risco associados à exposição de adolescentes à violência sexual. Av Enferm [Internet]. 2019; 37(3): 364-374. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/aven/v37n3/0121-4500-aven-37-03-364.pdf [ Links ]

12. Souza, VP, Gusmão TLA, Frazão LRSB, Guedes TG, Monteiro EMLM. Protagonismo de adolescentes no planejamento de ações para a prevenção da violência sexual. Texto contexto - enferm [Internet]. 2020; 29: e20180481. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-265x-tce-2018-0481 [ Links ]

13. Abreu PD, Santos ZC, Lúcio FPS, Cunha TN, Araújo EC, Santos CB, et al. Análise especial do estupro em adolescentes: Características e impactos. Cogitare Enferm [Internet]. 2019; 24. Disponível em: http://dx.doi.org/10.5380/ce.v24i0.59743 [ Links ]

14. Loder RT, Robinson TP. The demographics of patients presenting for sexual assault to US emergency departments. J Forensic Leg Med [Internet]. 2020; 69:101887. Disponível em: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jflm.2019.101887 [ Links ]

15. Yapp E, Pickett KE. Greater income inequality is associated with higher rates of intimate partner violence in Latin America. Public Health [Internet]. 2019; 175: 87-89. Disponível em: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2019.07.004 [ Links ]

16. Li X, Zheng H, Tucker W, Xu W, Wen X, Lin Y, et al. Research on Relationships between sexual identity adverse childhood experiences and non-suicidal self-injury among rural high School students in Less developed áreas of China. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. 2019; 16(17): 3158. Disponível em: http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16173158 [ Links ]

17. Caswell RJ, Ross JD, Lorimer K. Measuring experience and outcomes in patients reporting sexual violence who attend a healthcare setting: a systematic review. Sex Transm Infect [Internet]. 2019; 95(6):419-427. Disponível em: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/sextrans-2018-053920 [ Links ]

18. Almeida RAAS, Corrêa RGCF, Rolim ILTP, Hora JM, Linard AG, Coutinho NPS, et al. Conhecimento de adolescentes relacionados às doenças sexualmente transmissíveis e gravidez. Rev. Bras. Enferm. [Internet]. 2017; 70(5): 1033-1039. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-7167-2016-0531 [ Links ]

19. Brasil M, Cardoso F, Silva L. Conhecimento de escolares sobre infecções sexualmente transmissíveis e métodos contraceptivos. Rev Enferm UFPE [Internet]. 2019; 13(0): e242261. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.5205/1981-8963.2019.242261 [ Links ]

20. Carvalhaes RDS. Entre laços e nós: Narrativas de violência nas relações afetivo-sexuais de adolescentes de uma escola na região Costa Verde (RJ) [Dissertação]. Rio de Janeiro (RJ): Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro; 2019. 141 f. Disponível em: http://www.bdtd.uerj.br/tde_busca/arquivo.php?codArquivo=16216 [ Links ]

21. Schuster I, Krahé B. Prevalence of Sexual Aggression Victimization and Perpetration in Chile: A Systematic Review. Trauma Violence Abuse [Internet]. 2019; 20(2): 229-244. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838017697307 [ Links ]

22. Tordön R, Svedin CG, Fredlund C, Jonsson L, Priebe G, Sydsjö G. Backgroud, experience of abuse, and mental health among adolescents in out-of-home care: a cross-sectional study of a Swedish high school national sample. Nordic J Psychiatry [Internet]. 2019; 73(1): 16-23. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1080/08039488.2018.1527397 [ Links ]

23. Perdomo-Sandoval LA, Cardona-Gómez GDP, Urquijo-Velásquez LE. Situación de la violencia sexual en colombia, 2012-2016. Rev. Colomb. Enferm [Internet]. 2019; 18(1): 1-11. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.18270/rce.v18i1.2340 [ Links ]

24. Stark L, Seff I, Weber AM, Cislaghi B, Meinhart M, Bermudez LG, et al. Perpetration of intimate partner violence and mental health outcomes: sex- and gender-disaggregated associations among adolescentes and young adults in Nigeria. J Glob Hhealth [Internet]. 2020; 10(1): e010708. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.10.010708 [ Links ]

25. Acharyal K, Paudel YR, Silwal P. Sexual violence as a predictor of unintended pregnancy among married young women: evidence from the 2016 Nepal demographic and health survey. BMC pregnancy childbirth [Internet] 2019; 19(1): 196. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2342-3 [ Links ]

26. Dillard R, MaguirreJack K, Showalter K, Wolf KG Letson MM. Abuse disclosures of youth with problem sexualized behaviors and trauma symptomology. Child Abuse Negl [Internet]. 2019; 88: 201-211. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.11.019 [ Links ]

27. Lira MOSC, Diniz NMF, Couto TM, Vieira MCA, Justino TMV, Barbosa KMG. Limites e intolerâncias de mulheres sobreviventes do abuso sexual infantil. Rev. Enferm. UFPE [Internet]. 2019; 13: e239787. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.5205/1981-8963.2019.239787 [ Links ]

28. Lamis DA, Kapoor S, Evans APB. Childhood Sexual Abuse and Suicidal Ideation Among Bipolar Patients: Existential But Not Religious Well-Being as a Protective Factor. Suicide Life Threat Behav [Internet]. 2019; 49(2): 401-412. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12438 [ Links ]

29. Charak R, Tromp NB, Koot HM. Associations of specific and multiple types of childhood abuse and neglect with personality pathology among adolescents referred for mental health services. Psychiatry research [Internet] 2018; 270: 906-914. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.11.016 [ Links ]

30. Reid SD, Reddock R, Nickenig T. Action research improves services for child sexual abuse in one Caribbean nation: An example of good practice. Child abuse & Neglect [Internet]. 2019; 88: 225-234. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.11.018 lll [ Links ]

Received: September 03, 2021; Accepted: January 21, 2022

text in

text in