My SciELO

Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Enfermería Global

On-line version ISSN 1695-6141

Enferm. glob. vol.21 n.68 Murcia Oct. 2022 Epub Nov 28, 2022

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/eglobal.502451

Reviews

Early warning scales to track clinically deteriorating in emergency medical services: an integrative review

1Federal University of Triângulo Mineiro, Uberaba - MG, Brazil

Objective:

To identify the scientific evidence in the literature on the use of early warning scales in the identification of adult and elderly patients in clinical deterioration in emergency medical services.

Methods:

Integrative review, supported by the recommendation Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses, with a search mnemonic based on the Populacion - Interest Phenomenon - Context (PICo) strategy, performed in the sources: US National Library of Medicine National Institutes Database Search of Health, Web of Science, SciVerse Scopus, Latin American and Caribbean Literature in Health Sciences and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature. Rayyan was used in selection and content analysis to analyze the findings.

Results:

691 articles were identified, of which 22 composed the sample and 27 scales were listed, with emphasis on the National Early Warning Score, National Early Warning Score 2, Quick Sepsis Related Organ Failure Assessment and Modified Early Warning Score. The scales had similar assessment parameters, characterized by heart rate, respiratory rate, systolic blood pressure, temperature, oxygen saturation and level of consciousness.

Conclusion:

27 scales were listed with similar evaluation parameters, in which four were the most prevalent and of these the National Early Warning Score proved to be the most accurate, however evidence shows that the Modified Early Warning Score is the most used in emergency medical services.

Keywords: Clinical Deterioration; Emergency Medical Services; Patient Safety; Vital Signs

INTRODUCTION

Most patients admitted to critical care units who evolve to cardiorespiratory arrest (CRA) or clinical worsening present early signs and symptoms of clinical deterioration, characterized by altered vital signs associated with other neurological, respiratory, and cardiovascular clinical signs1.

Clinical deterioration, in most cases, occurs due to the lack of adequate monitoring and recording of vital signs, which makes it difficult for the healthcare team to recognize the worsening process of the patient's clinical condition, leading to an increase in CRA and death in the hospital environment2.

To detect clinical deterioration of critically ill patients during their stay in the hospital, in the last decades scales have been developed with resources to establish parameters that identify worsening of the clinical picture and point out signs that demonstrate instability3. In view of the above, several early warning scales known as "Early Warning Scores" (EWS) have been developed and used with the purpose of identifying the patient at risk of clinical deterioration4. These scales are tools applied at the bedside to systematize monitoring and allow early intervention in the patient, enabling the determination of risk scores for clinical deterioration4.

EWS include vital sign data such as respiratory rate (RR), heart rate (HR), systolic blood pressure (SBP), peripheral oxygen saturation (SaO2), temperature (T), and level of consciousness, and some include criteria such as age, urine output, and laboratory values, among others1)(2)(3)(4.

Each parameter receives a specific score that, added to the others, determines the severity of the condition, and higher scores portray greater clinical instability5. Some scales, in face of the score obtained, indicate a conduct to be taken by the professional, such as: immediate assessment by the nurse or physician, more frequent observation and monitoring, or referral to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU)5.

It is observed in the literature that the monitoring of patients is still deficient in Emergency Medical Services (EMS), hindering early detection of clinical deterioration6. Public health services show a daily context of overcrowding, shortage of material and human resources, patients with unknown history and heterogeneous profile, besides an intense and unpredicTable demand for care6.

In this scenario, it is important to apply the EWS as a strategy to organize the process of patient care in critical care environments, thus enhancing the quality and safety of care, as well as contributing to paving the way for a better prognosis with shorter hospitalization and lower resource consumption1)(2)(3)(4.

In the literature search, it was found that there is a scarcity of national publications on the application and performance of assessment scales for recognition of cases of clinical deterioration6. Given this scientific gap, the need arises to investigate what scientific evidence exists in the literature on the use of EWS in the identification of adult and elderly patients in clinical deterioration in EMSs?

Thus, this study aimed to identify the existing scientific evidence in the literature on the use of early warning scales in identifying adult and elderly patients in clinical deterioration in emergency medical services.

METHOD

This is an integrative literature review, supported by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) recommendation7, which gathers and synthesizes the results of research on a theme or delimited question in a systematic and orderly manner, contributing to the deepening of knowledge on the investigated theme and to support decision making and improvement of clinical practice8.

The following steps were followed: (1) identification of the research question; (2) establishment of the inclusion and exclusion criteria; (3) database search; (3) categorization of the information to be extracted from the studies; (4) evaluation of the studies included in the review; (5) interpretation of the results; and (6) synthesis of knowledge8.

In the first step, the topic that addressed the EWSs used in EMSs to screen patients in clinical deterioration was identified and the research question was formulated based on the Population - Interest Phenomenon - Context (PICo) strategy(9). The acronym "P" (Population) was represented by adult and elderly patients; the acronym "I" (Phenomenon of Interest) was conFigured by the identification of EWSs to identify patients in clinical deterioration; and the acronym "Co" (Context of the study) was represented by SMEs. Thus, the research question emerged: what scientific evidence exists in the literature on the use of EWSs in identifying adult and elderly patients in clinical deterioration in EMSs?

In the second step, the inclusion criteria were defined: primary studies that answered the research question. Reviews, theses, dissertations, opinion articles, commentaries, essays, preliminary notes, manuals, books, and book chapters were excluded.

Utilizaram-se as seguintes fontes de informação: US National Library of Medicine National Institutes Database Search of Health (PubMed®/Medline), Web of Science, SciVerse Scopus, Latin American and Caribbean Literature on Health Sciences (LILACS) and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL).

The search for scientific evidence occurred in May 2021 using the health descriptors available in the Health Sciences Descriptors Portal (DeCS) in the Virtual Health Library (VHL) and by the controlled descriptors from the Medical Subject Headings, detected through the respective search strategy, specific for each database selected and validated by a librarian.

For the PubMed® database search, we adopted the controlled descriptors, in the English language, identified in the Medical Subjects Headings (MeSH): Adult; Aged; "Clinical Deterioration"; “Emergency Medical Services”; “Early Warning Score”. The strategies were used: (Adult AND Aged AND “Clinical Deteriorations” OR “Deterioration, Clinical” AND “Early Warning Score” OR “Early Warning Scores” OR “Score, Early Warning” OR “Scores, Early Warning” AND “Emergency Medical Services” OR “Emergency Services, Medical” OR “Medical Emergency Service” OR “Service, Medical Emergency” OR “Service, Emergency Medical”).

In Web of Science the following English language descriptors were adopted: Adult; Aged; "Clinical Deterioration"; “Emergency Medical Services”; “Early Warning Score”. The strategies were carried out: TS=(Adult AND Aged AND “Clinical Deteriorations” OR “Deterioration, Clinical” AND “Early Warning Score” OR “Early Warning Scores” OR “Score, Early Warning” OR “Scores, Early Warning” AND “Emergency Medical Services” OR “Emergency Services, Medical” OR “Medical Emergency Service” OR “Service, Medical Emergency” OR “Service, Emergency Medical”).

In SCOPUS, we used the controlled descriptors in the English language and identified in the Medical Subjects Headings (MeSH) Adult; Aged; "Clinical Deterioration"; “Emergency Medical Services”; “Early Warning Score”. Strategies were elaborated: TITLE-ABS-KEY=(Adult AND Aged AND “Clinical Deteriorations” OR “Deterioration, Clinical” AND “Early Warning Score” OR “Early Warning Scores” OR “Score, Early Warning” OR “Scores, Early Warning” AND “Emergency Medical Services” OR “Emergency Services, Medical” OR “Medical Emergency Service” OR “Service, Medical Emergency” OR “Service, Emergency Medical”).

In LILACS, the controlled descriptors were present in the Health Sciences Descriptors (Decs) in Portuguese Adult; Elderly; "Clinical Deterioration"; "Emergency Medical Services"; "Early Warning Scale" and their versions in English and Spanish. The strategies: (Adult OR Elderly AND "Clinical Deterioration" AND "Emergency Medical Services" AND "Early Warning Scale") and their versions in English and Spanish were adopted.

In CINAHL, the following controlled descriptors were identified in Titles/Subjects in English: Adult; Aged; "Clinical Deterioration"; "Emergency Medical Services"; "Early Warning Score". The strategy was adopted: SU=((Adult OR Aged AND ("Clinical Deteriorations") AND ("Early Warning Score") AND ("Emergency Medical Services")).

To select the studies following the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the titles, and abstracts of 691 studies were read a priori by two researchers independently, using the free, single-version web review software called Rayyan Qatar Computing Research Institute (Rayyan QCRI), which eliminates duplicate articles, speeds up the initial screening using a reliable semi-automation process, and incorporates a high level of usability and efficiency in the process10. After the selection by titles and abstracts, 38 studies that caused disagreement among researchers were given to a third party, responsible for making the decision of inclusion or exclusion, and then 57 articles were read in full by the same researchers, independently, to define the final sample of 22 manuscripts.

Next, the information to be extracted from the selected studies was defined. To this end, we used the criteria of a validated instrument11 and adapted to the context of this study, extracting the following information: author, early warning scale, year of publication, objective, type of study, results and conclusion, and level of evidence12.

In the next step, the included studies were read in their entirety and a critical evaluation of the methodological quality was performed using the Critical Appraisals Skills Programme (CASP) instrument, which includes 10 items related to: objective; adequacy of the method; presentation of the theoretical and methodological procedures; sample selection criteria; sample detailing; relationship between researchers and respondents (randomization/blinding); respect for ethical aspects; rigor in data analysis; property to discuss results; and contributions and limitations of the research. Subsequently, the studies were classified as level A (score between 6 and 10 points), being considered of good methodological quality and reduced bias or level B (up to 5 points), meaning satisfactory methodological quality, but with considerable risk of bias13. After this step, the interpretation of results and synthesis of knowledge occurred.

RESULTS

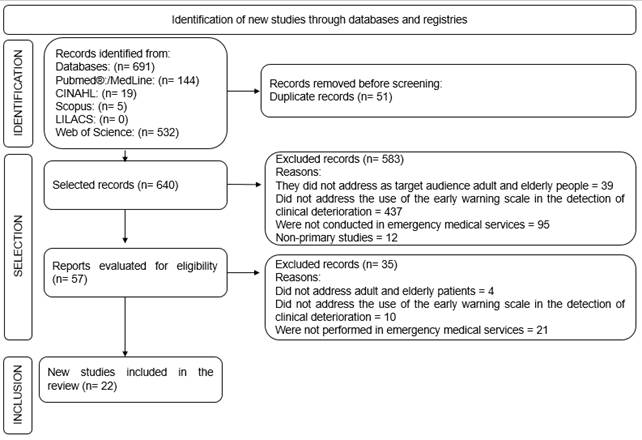

A priori, 691 studies were identified and, of these, 22 made up the final sample of this research. The selection process is shown in Figure 1, below.

Source: authors, 2021. CINAHL: Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; LILACS: Latin American and Caribbean Literature on Health Sciences.

Figure 1: Flowchart of identification, selection, and inclusion of studies, based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) recommendation. Uberaba, MG, Brazil, 2021.

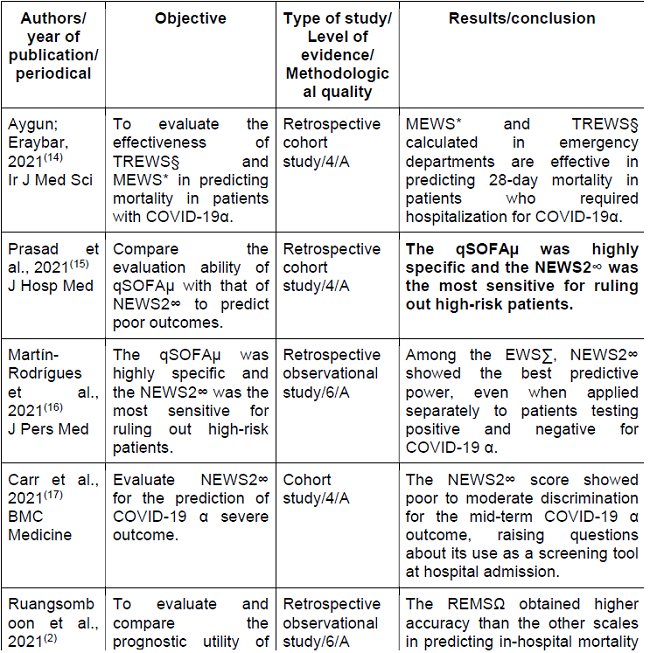

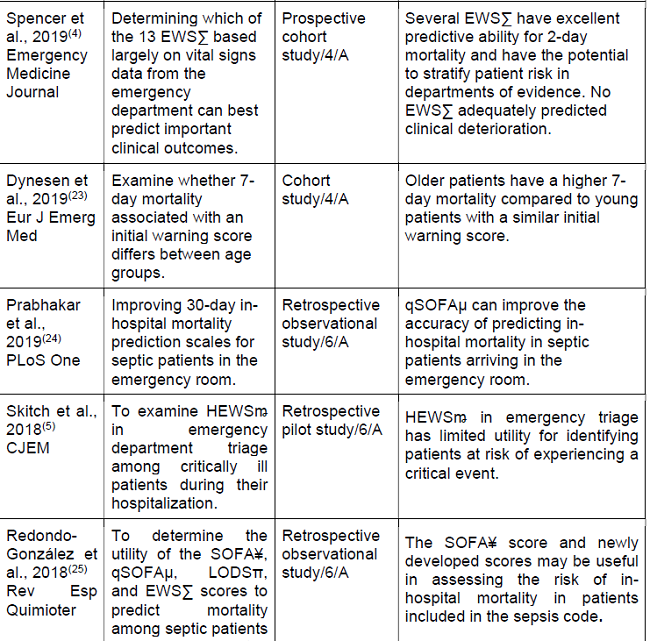

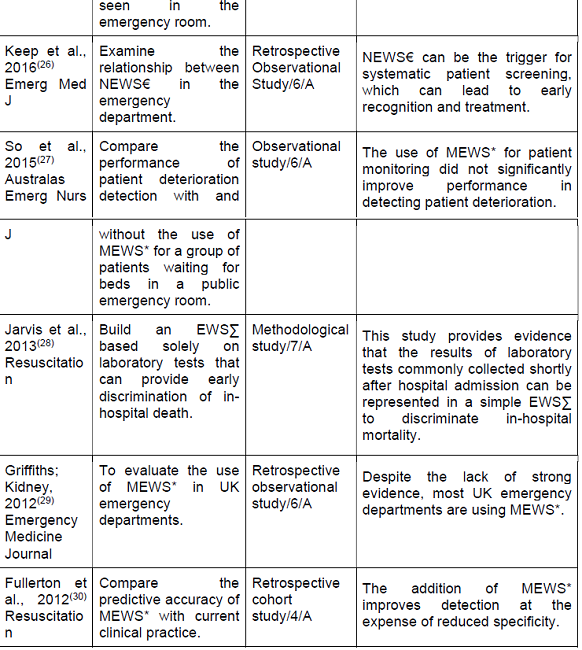

Chart 1 below presents the characterization of the studies included in the sample.

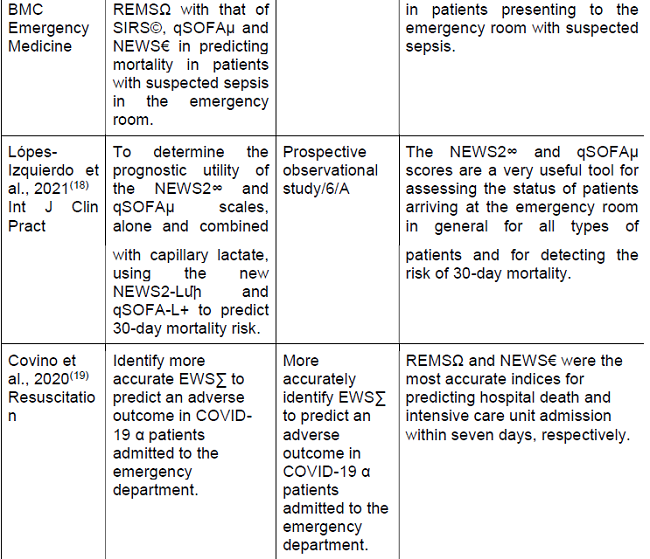

Chart 1: Characterization of the studies that comprised the sample of the integrative literature review. Uberaba, MG, Brazil, 2021.

Chart 1 (cont.): Characterization of the studies that comprised the sample of the integrative literature review. Uberaba, MG, Brazil, 2021.

Chart 1 (cont.): Characterization of the studies that comprised the sample of the integrative literature review. Uberaba, MG, Brazil, 2021.

Chart 1 (cont.): Characterization of the studies that comprised the sample of the integrative literature review. Uberaba, MG, Brazil, 2021.

Chart 1 (cont.): Characterization of the studies that comprised the sample of the integrative literature review. Uberaba, MG, Brazil, 2021.

Source: authors, 2021.

*Modified Early Warning Score;

§Triage Early Warning Score;

αCoronavirus Disease;

∑Early Warning Score,

€National Early Warning Score,

¥Sequential Organ Failure Assessment,

µQuick Sepsis Related Organ Failure Assessment,

πLogistic Organ Dysfunction System;

∞National Early Warning Score 2;

ΩRapid Emergency Medicine Score;

©Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome Criteria;

™Tidling Opsporing af Kritisk Sygdom;

ↄEarly Warning Score O2;

¬National Early Warning Score C;

ꬺHamilton Early Warning Score;

+Quick Sepsis Related Organ Failure Assessment Lactato;

ﬕNational Early Warning Score 2 - Lactato

The studies were published between 2012 and 2021 internationally and were mostly characterized by level 6 evidence and rated level A for good methodological quality and reduced bias.

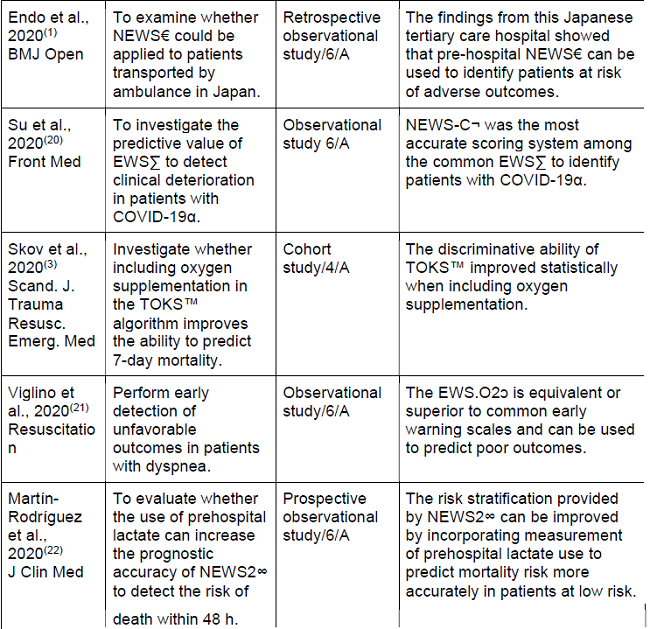

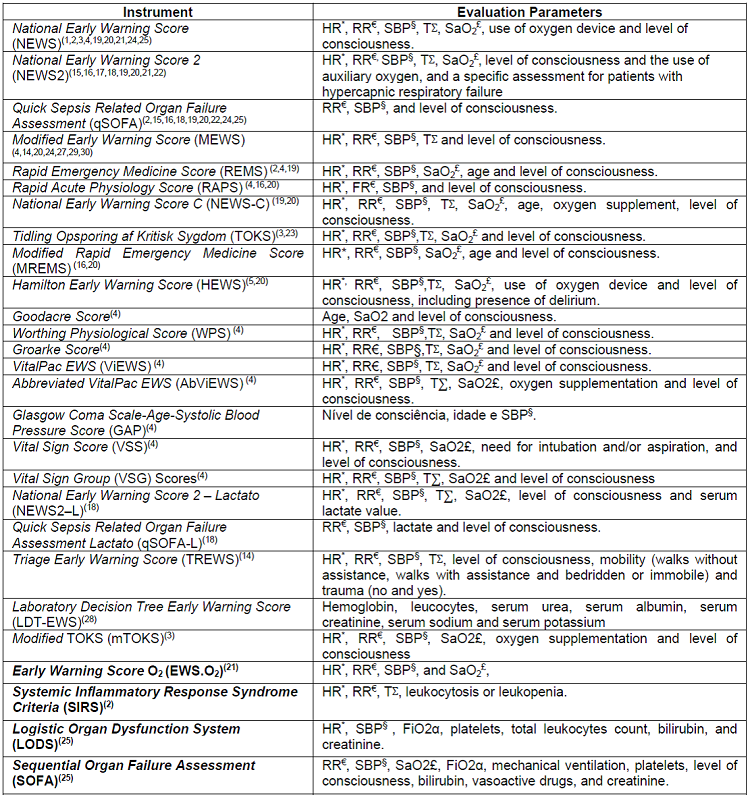

Chart 2, following, presents the main scales and the parameters used in identifying adult and elderly patients in clinical deterioration addressed in the scales.

Chart 2: Identification parameters of adult and elderly patients in clinical deterioration presented by the scales identified in the sample. Uberaba, MG, Brazil, 2021.

Source: authors, 2021.

*Heart Rate,

€Respiratory Rate,

§Systolic Blood Pressure,

£Oxygen Saturation,

∑Temperature,

αFraction of Inspired Oxygen

Among the 27 scales identified, NEWS1)(2)(3)(4)(19)(20)(21)(24)(26, NEWS 215)(16)(17)(18)(19)(20)(21)(22, qSOFA2)(15)(16)(18)(19)(20)(22)(24)(25 and MEWS4)(14)(20)(24)(27)(29)(30 were the most frequently mentioned by the studies that comprised the sample of the present review. Regarding the EWS assessment parameters, there was a predominance of physiological parameters characterized by heart rate, respiratory rate, systolic blood pressure, temperature, oxygen saturation and level of consciousness1)(2)(3)(4)(5)(14)(15)(16)(17)(18)(19)(20)(21)(22)(23)(24)(25)(26)(27)(28)(29)(30.

DISCUSSION

The use of early warning scales based on physiological parameters allows the detection of clinical deterioration and the assessment of the risk of severe events such as unexpected death, cardiac arrest, and transfers to ICU beds4.

The sample of identified findings is mostly supported by observational level 6 manuscripts, with good methodological quality and reduced bias. However, the low level of evidence implies the incentive for the development of methodologically well-designed studies, characterized by experimental studies, to explore and compare the effectiveness of EWSs, enabling an evidence-based clinical decision in favor of prevention, resolution, management and reduction of risks and complications13.

This study is unprecedented in nursing science because it brings together in a single article scientific evidence citing the use of scales to identify adult and elderly patients in clinical deterioration in EMSs and their assessment parameters to contribute to the development of new scientific research, methodologically well designed.

Twenty-seven scales comprised the sample of the present study. Of these, NEWS1)(2)(3)(4)(19)(21)(24)(26 was noteworthy, in which an observational study of patients with COVID-19 and admitted to an emergency department of a university hospital in Rome showed that NEWS is among the most accurate tools to predict deterioration of the patient outside the ICU19.

In line with the present research, an observational, retrospective study carried out in the emergency department of a university hospital, located in the United Kingdom, complements the point that NEWS, can also be used to detect and triage patients in clinical deterioration due to septic shock26.

It is noteworthy that NEWS has been updated, which contributed to the development and validation of NEWS2, which was also highlighted in this review15)(16)(17)(18)(19)(20)(21)(22. This scale was evidenced by an observational study carried out with adult patients with suspected COVID-19 infection, admitted to an emergency department in Spain, where it was shown that when compared to the other EWSs, NEWS2 stands out for having a better predictive capacity and a higher sensitivity for COVID-19 cases regarding the detection of clinical deterioration16.

NEWS2, also stood out in an observational, prospective, multicenter study conducted in four nursing departments when it evidenced that this scale is a tool with significant utility to assess the status of patients who are admitted to the emergency room, regardless of their clinical condition, in addition, they are useful to detect the risk of mortality within 30 days22.

Like NEWS2, a prevalence of qSOFA was identified in this review2)(15)(16)(18)(19)(20)(22)(24)(25. A cohort study in an emergency department demonstrated that the qSOFA is highly specific for detecting high-risk patients15. In contrast, a Wuhan study of patients infected with COVID-19 has shown that the qSOFA, although relevant, is less sensitive than other EWS to predict early deterioration of respiratory function in patients diagnosed with COVID-1922.

In addition to the scales presented, the literature has highlighted the MEWS as a useful tool to predict early deterioration4)(14)(20)(24)(27)(29)(30. Research aimed to evaluate the use of MEWS in UK emergency departments indicates that this scale is the most used in hospital settings29. Furthermore, an observational study conducted in an emergency department in Hong Kong adds that the use of the MEWS may be beneficial for health professionals who have less clinical experience in identifying clinical deterioration in patients because it is a tool that is easy to apply and understand27.

Regarding the evaluation parameters of the early warning scales, most of them are composed of physiological parameters characterized by heart rate, respiratory rate, systolic blood pressure, temperature, oxygen saturation and level of consciousness. Scientific evidence shows that assessment by physiological parameters is effective and reliable in detecting clinical deterioration of adult and elderly patients admitted to EMSs14)(15)(16)(17)(19)(24)(25.

In summary, it was identified that the ideal scale for identifying clinical deterioration is one that broadly covers physiological parameters and can accurately identify what it is intended to measure, that is easy to handle, has a high level of interobserver agreement, reproducibility, and predictive value, and rapidly predicts patient deterioration, morbidity, and mortality1)(2)(3)(4)(19)(20)(21)(24)(26.

In this context, the multi-professional team, specifically the nursing professional, must choose the tool that best fits the health service, besides the fact that they must be aware of the signs and symptoms that characterize the clinical deterioration of adult and elderly patients because they are often in the front line, which leads them to be considered one of the professionals who can early identify the patient's evolution to CRA and, especially, outline possible behaviors that prevent a poor prognosis1)(2)(3)(4)(19)(20)(21)(24)(26.

A priori, the low level of evidence of the studies and the lack of clarity in the description of the assessment parameters are considered a limitation of the present study, which made it difficult to understand and identify the form of assessment of the listed scales. In addition, it is noteworthy that most scales do not establish a protocol of conduct to be adopted when assessing the patient in clinical deterioration. Therefore, it is suggested that research be conducted with a high level of evidence, characterized by experimental and quasi-experimental studies that seek to investigate the effectiveness of the scales and that can establish a plan of care for patients who present worsening of clinical condition.

CONCLUSION

We identified 27 early warning scales used to identify clinical deterioration in adult and elderly patients, of these, the most prevalent were NEWS, NEWS 2, qSOFA and MEWS. Among those that stood out, NEWS proved to be the most accurate, however, evidence shows that MEWS is the most used in EMSs. The scales, in general, have similar assessment parameters, characterized by heart rate, respiratory rate, systolic blood pressure, temperature, oxygen saturation, and level of consciousness.

This study contributes to teaching, research, and assistance in health and nursing, a priori, by structuring a theoretical framework about the main scales for identifying adult and elderly patients in clinical deterioration in EMSs and presenting their assessment parameters, which can help the work of nursing, favoring better decision making for clinical practice, for deployments, use, and training, and also to subsidize the development of new scientific research, methodologically well designed, which propose to validate them and compare their effectiveness.

REFERENCIAS

1. Endo T, Yoshida T, Shinozaki T, Motohashi T, Hsu H-C, Fukuda S, et al. Efficacy of prehospital National Early Warning Score to predict outpatient disposition at an emergency department of a Japanese tertiary hospital: a retrospective study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(6):e034602. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034602. [ Links ]

2. Ruangsomboon O, Boonmee P, Limsuwat C, Chakorn T, Monsomboon A. The utility of the rapid emergency medicine score (REMS) compared with SIRS, qSOFA and NEWS for Predicting in-hospital Mortality among Patients with suspicion of Sepsis in an emergency department. BMC Emerg Med. 2021;21(1):2. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-52232/v1. [ Links ]

3. Skov MJ, Dynesen J, Jessen MK, Liesanth JY, Mackenhauer J, Kirkegaard H. Including oxygen supplement in the early warning score: a prediction study comparing TOKS, modified TOKS and NEWS in a cohort of emergency patients. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2020;28(1):26. doi: 10.1186/s13049-020-00720-1. [ Links ]

4. Spencer W, Smith J, Date P, Tonnerre E de, Taylor DM. Determination of the best early warning scores to predict clinical outcomes of patients in the emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2019;36(12):716-21. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2019-208622. [ Links ]

5. Skitch S, Tam B, Xu M, McInnis L, Vu A, Fox-Robichaud A. Examining the utility of the Hamilton early warning scores (HEWS) at triage: Retrospective pilot study in a Canadian emergency department. Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2018;20(2):266-74. doi: 10.1017/cem.2017.21. [ Links ]

6. Considine J, Rawet J, Currey J. The effect of a staged, emergency department specific rapid response system on reporting of clinical deterioration. Australas Emerg Nurs J. [on line]. 2015;18(4):218-26. doi: 10.1016/j.aenj.2015.07.001. [ Links ]

7. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bussoyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [ Links ]

8. Mendes KDS, Silveira RC de CP, Galvão CM. Revisão integrativa: método de pesquisa para a incorporação de evidências na saúde e na enfermagem. Texto contexto - enferm. 2008;17:758-64. doi: 10.1590/S0104-07072008000400018. [ Links ]

9. Sousa LMM, Marques JM, Firmino CF, Frade F, Valentim OS, Antunes AV. Modelos de formulação da questão de investigação na prática baseada na evidência. Revista investigação em enfermagem. [Internet] 2018 [cited 2021 Jan 18];(N Esp):31-39. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325699143_MODELOS_DE_FORMULACAO_DA_QUESTAO_DE_INVESTIGACAO_NA_PRATICA_BASEADA_NA_EVIDENCIA [ Links ]

10. Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews. 2016;5(1):210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4. [ Links ]

11. Ursi ES, Gavão CM. Prevenção de lesões de pele no perioperatório: revisão integrativa da literatura. Rev Latino-Am Enfermagem. 2006;14:124-31. doi: 10.1590/S0104-11692006000100017. [ Links ]

12. Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt E, organizadores. Evidence-based practice in nursing & healthcare: a guide to best practice. Fourth edition. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2019. 782 p. [ Links ]

13. Alencar DL, Marques APO, Leal MCC, Viera JCM. Fatores que interferem na sexualidade de idosos: uma revisão integrativa. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva. 2014;19(8):3.533-42. doi: 10.1590/1413-81232014198.12092013. [ Links ]

14. Aygun H, Eraybar S. The role of emergency department triage early warning score (TREWS) and modified early warning score (MEWS) to predict in-hospital mortality in COVID-19 patients. Ir J Med Sci. 1-7, 2021. doi: 10.1007/s11845-021-02696-y. [ Links ]

15. Prasad PA, Fang MC, Martinez SP, Liu KD, Kangelaris KN. Identifying the Sickest During Triage: Using Point-of-Care Severity Scores to Predict Prognosis in Emergency Department Patients With Suspected Sepsis. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(8):453-61. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3642. [ Links ]

16. Martín-Rodríguez F, Martín-Conty JL, Sanz-García A, Rodríguez VC, Rabbione GO, Cebrían Ruíz I, et al. Early Warning Scores in Patients with Suspected COVID-19 Infection in Emergency Departments. J Pers Med. 2021;11(3):170. doi: 10.3390/jpm11030170. [ Links ]

17. Carr E, Bendayan R, Bean D, Stammers M, Wang W, Zhang H, et al. Evaluation and improvement of the National Early Warning Score (NEWS2) for COVID-19: a multi-hospital study. BMC Med. 2021;19(1):23. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01893-3. [ Links ]

18. López-Izquierdo R, Martín-Rodríguez F, Santos Pastor JC, García Criado J, Fadrique Millán LN, Carbajosa Rodríguez V, et al. Can capillary lactate improve early warning scores in emergency department? An observational, prospective, multicentre study. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75(4):e13779. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.137. [ Links ]

19. Covino M, Sandroni C, Santoro M, Sabia L, Simeoni B, Bocci MG, et al. Predicting intensive care unit admission and death for COVID-19 patients in the emergency department using early warning scores. Resuscitation. 2020;156:84-91. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2020.08.124 [ Links ]

20. Su Y, Ju M, Xie R, Yu S, Zheng J, Ma G, et al. Prognostic Accuracy of Early Warning Scores for Clinical Deterioration in Patients With COVID-19. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;7:624255. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.624255. [ Links ]

21. Viglino D, L'her E, Maltais F, Maignan M, Lellouche F. Evaluation of a new respiratory monitoring tool "Early Warning ScoreO2" for patients admitted at the emergency department with dyspnea. Resuscitation. 2020;148:59-65. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2020.01.004. [ Links ]

22. Martín-Rodríguez F, López-Izquierdo R, Delgado Benito JF, Sanz-García A, Del Pozo Vegas C, Castro Villamor MÁ, et al. Prehospital Point-Of-Care Lactate Increases the Prognostic Accuracy of National Early Warning Score 2 for Early Risk Stratification of Mortality: Results of a Multicenter, Observational Study. J Clin Med. 2020;9(4):E1156. doi: 10.3390/jcm9041156. [ Links ]

23. Dynesen J, Skov MJ, Mackenhauer J, Jessen MK, Liesanth JY, Ebdrup L, et al. The 7-day mortality associated with an early warning score varies between age groups in a cohort of adult Danish emergency department patients. Eur J Emerg Med. 2019;26(6):453-7. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000623. [ Links ]

24. Prabhakar SM, Tagami T, Liu N, Samsudin MI, Ng JCJ, Koh ZX, et al. Combining quick sequential organ failure assessment score with heart rate variability may improve predictive ability for mortality in septic patients at the emergency department. PLoS One. 2019;14(3):e0213445. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0213445. [ Links ]

25. Redondo-González A, Varela-Patiño M, Álvarez-Manzanares J, Oliva-Ramos JR, López-Izquierdo R, Ramos-Sánchez C, et al. Assessment of the severity scores in patients included in a sepsis code in an Emergency Departament. Rev Esp Quimioter. 2018;31(4):316-22. [ Links ]

26. Keep JW, Messmer AS, Sladden R, Burrell N, Pinate R, Tunnicliff M, et al. National early warning score at Emergency Department triage may allow earlier identification of patients with severe sepsis and septic shock: a retrospective observational study. Emerg Med J. 2016;33(1):37-41. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2014-204465. [ Links ]

27. So S-N, Ong C-W, Wong L-Y, Chung JYM, Graham CA. Is the Modified Early Warning Score able to enhance clinical observation to detect deteriorating patients earlier in an Accident & Emergency Department? Australas Emerg Nurs J. 2015;18(1):24-32. doi: 10.1016/j.aenj.2014.12.001. [ Links ]

28. Jarvis SW, Kovacs C, Badriyah T, Briggs J, Mohammed MA, Meredith P, et al. Development and validation of a decision tree early warning score based on routine laboratory test results for the discrimination of hospital mortality in emergency medical admissions. Resuscitation. 2013;84(11):1494-9. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.05.018. [ Links ]

29. Griffiths JR, Kidney EM. Current use of early warning scores in UK emergency departments. Emerg Med J. 2012;29(1):65-6. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2011-200508 [ Links ]

30. Fullerton JN, Price CL, Silvey NE, Brace SJ, Perkins GD. Is the Modified Early Warning Score (MEWS) superior to clinician judgement in detecting critical illness in the pre-hospital environment? Resuscitation. 2012;83(5):557-62. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.01.004. [ Links ]

Received: November 24, 2021; Accepted: February 09, 2022

text in

text in