Introduction

Most of the research on violence in dating relationships has focused on the study of physical aggression. However, after more than a decade of research, it has been confirmed that psychological violence in any of its forms (verbal aggression, dominance, and jealousy) is much more prevalent in young population (Cascardi & Avery-Leaf 2015; Cascardi, Avery-Leaf, O’Leary, & Smith Slep, 1999; Hird 2000; Jackson, Cram, & Seymour, 2000; Muñoz-Rivas, Graña, O’Leary, & González, 2007b; Orpinas, Nahapetyan, Song, McNicholas, & Reeves, 2012; Shook, Gerrity, Jurich, & Segrist, 2000; Ybarra, Espelage, Langhinrichsen-Rohling, Korchmaros, & Boyd, 2016). Moreover, with regard to its relation with other types of aggression, such as physical or sexual aggression, psychological violence is considered a good indicator of these other types of violent behaviors aimed at the partner (Cano, Avery-Leaf, Cascardi, & O’Leary, 1998; Muñoz-Rivas, Graña, O’Leary, & González, 2009).

It is possible to identify different forms of psychological violence in dating relationships between young people and adolescents. O’Leary & Smith Slep (2003) conducted a study with adolescents finding three subtypes of psychological violence: (1) verbal aggression, (2) dominant, coercive and controlling behaviors, and (3) jealous behaviors. Verbal aggression is the most studied form of psychological aggression and includes insults, threats, saying something to the couple with the intention of bothering him/her, and periods of aggressive silence. Dominant tactics consist of controlling the activities of the couple in their social and family area. Among the most common control tactics is the isolation of the victim, that is, making him/her feel that he/she must break him/her relationship with friends and family or that it is not appropriate to have friends of the opposite sex (Smith & Donnelly, 2001). While jealous tactics can be defined as the desire to control and possess the couple and the subsequent behaviors that are carried out, such as checking what the couple does and demanding that they inform him/her of where he/she has been (Muñoz-Rivas et al., 2007b). Although there are still few studies that analyze these other forms of psychological violence in dating relationships, those that are carried out indicate that the prevalence of the use of dominant and jealous tactics is quite high in Spanish samples, with percentages between 60%-70% for the use of jealous tactics and around 30%-40% for dominant tactics (Muñoz-Rivas et al., 2007b; Sebastián, Verdugo, & Ortiz, 2014).

Hence, in recent years, emphasis has been placed on the need to have valid and reliable instruments to assess the presence of this type of behaviors in intimate relations established at early ages. One of the first instruments created for this purpose was the Psychological Maltreatment of Women Inventory (PMWI; Tolman 1989, 1999) which had 58 items and two subscales: Dominance/Isolation and Emotional/Verbal Abuse. Years later, Kasian and Painter (1992) administered a modified version of the PMWI to a sample of 1625 college students of both sexes, analyzing the construct validity of the instrument and concluding that the PMWI had 6 differentiated factors, among which were dominance and jealousy. Drawing on these factors, Kasian and Painter proposed the Dominating and Jealous Tactics Scale (DJTS), made up of 11 items and 2 subscales: dominant and jealous tactics.

The DJTS has been used in numerous investigations both in adult population (Kar & O’Leary, 2013; Ruiz-Hernández, García-Jiménez, Llor-Esteban, & Godoy-Fernández, 2015) and in samples of young adults and adolescents (Cascardi & Avery-Leaf, 2015; Cascardi et al., 1999; Muñoz-Rivas et al., 2007b, 2009), although in Spain, this instrument has not been adapted to this type of population. Therefore, the goal of the present study was to adapt and validate the DJTS in a broad sample of adolescents and young adults from Spain, in order to determine the psychometric guarantees of the instrument for this population. The hypotheses that we propose in this study are: (1) the scale is made up of two correlated factors: Dominant Tactics and Jealous Tactics, as in the original study; (2) both factors will present satisfactory reliability; (3) regarding convergent validity, DJTS will correlate with physical and psychological aggression towards partner measured with the Modified Conflict Tactics Scale; (4) regarding known groups validity, we expect to find significant differences in DJTS as a function of age and sex.

Method

Participants

The total sample of the study was made up of 8105 adolescents and young adults, 54.7% females and 45.3% males, aged between 14 and 26, mean age 19.11 years (SD = 3.29). By frequencies, 48.9% of the sample was aged between 14 and 18, and 51.1% between 19 and 26. With regard to occupation, 75.6% are studying, 14% are working, 10.3% are studying and working, and 0.2% does not know or does not reply. The participants in this study stated that they had a partner at the time of the evaluation or had had one previously.

Instruments

Sociodemographic Questionnaire. We collected information by means of different questions concerning sociodemographic data such as age, sex, and occupation, as well as information about couple relations such as whether they had had a partner previously or whether they had one currently at the time of the assessment.

The Dominating and Jealous Tactics Scale (DJTS; Kasian & Painter, 1992). This scale is made up of 11 items and 2 subscales: (a) Dominant Tactics, which included 7 items that assess controlling or coercive behaviors in the couple relationships of adolescents and young adults (e.g., "I have tried to prevent my boyfriend/girlfriend from talking to or seeing his/her family”); and (b) Jealous Tactics, made up of 4 items referring to jealous behaviors (e.g., "I have been jealous and suspicious of my boyfriend's/girlfriend's friends”). The DJTS is rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (very frequently), with bidirectional questions that provide two measures: perpetration or what the respondent does to his/her partner, and victimization or what the partner does to the respondent. With regard to the psychometric properties of the DJTS in samples of young adults and adolescents, significant correlations between the two subscales, dominant and jealous tactics, and physical and psychological aggression measured with the Modified Conflict Tactics Scale (M-CTS; Neidig, 1986) were found in high school students (Cascardi et al., 1999), and satisfactory reliability data with Cronbach alpha coefficients of .72 for Dominant Tactics and of .76 for Jealous Tactics, also in samples of high school students (Cano et al., 1998).

The Modified Conflict Tactics Scale (M-CTS; Neidig, 1986; Spanish adaptation of Muñoz-Rivas, Andreu, Graña, O’Leary, & González, 2007a). The modified version of the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS; Straus, 1979) was validated, supporting 2-factor models for males and females: Psychological and Physical Aggression (Cascardi et al., 1999). The Spanish version yielded a 4-factor model for males and females: Negotiation, Verbal/Psychological Aggression, Minor Physical Aggression and Severe Physical Aggression. It is made up of 18 items, with bidirectional questions (victim/aggressor), and a 5-point Likert-type response format, with frequencies ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (very frequently). In the Spanish adaptation, reliability, measured through Cronbach's alpha coefficient in the subscales of Aggression, ranged from .65 to .82 for Perpetration and from .63 to .82 for Victimization.

Procedure

The Spanish adaptation of the DJTS in young adults and adolescents of the Region of Madrid was performed in the following phases: (a) Linguistic and cultural adaptation of the scale, following the guidelines of the International Tests Commission, (ITC; Hambleton, 2001). Two groups of experts in both languages and cultures, as well as in the topic of violence and aggression in dating relationships translated the scale independently. Subsequently, a consensual version was reached by the translators and the research team. (b) Administration of the scale within the framework of an investigation centered on the analysis of aggressive behaviors in dating relationships of adolescents and young adults. The entire sample was extracted from a total of 26 schools belonging to the Region of Madrid. There were 20 public schools of Secondary Education and Vocational Training, 3 public universities, and 3 private universities. The participants were selected as a function of the centers’ possibilities of collaborating, and sampling was carried out taking each classroom as sample unit, such that once numbered, the classrooms were randomly selected to obtain a sufficient sample for the present adaptation.

Data Analysis

All the statistical analyses were performed with the statistical packages SPSS 19.0 and AMOS 20. The reliability of the scale was analyzed by means of Cronbach’s internal consistency alpha coefficient. To assess construct validity, we used three methods: (a) convergent validity, for which we calculated Pearson’s correlation coefficients between the DJTS scores and the scores of the subscales of Verbal Aggression and Physical Aggression of the M-CTS; (b) Known-groups validity, for which we calculated Student's t in order to confirm the existence of differences in the DJTS as a function of participants' age and gender. These two analyses, along with the descriptive statistics, were performed with the SPSS 19.0 software; (c) Confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) with the AMOS 20 program, to analyze three possible models to determine which provided a better fit to the data. The fit indexes used were: adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and comparative fit index (CFI). GFI, AGFI and CFI values equal to or higher than .90, are considered acceptable, and for RMSEA, values equal to or lower than .05 are considered excellent (Bentler, 2006; Byrne, 2012; García-Ael, Recio, & Silván-Ferrero, 2018; Hu & Bentler, 1999; Kline, 2010-, López-Ramos, Navarro-Pardo, Fernández-Muñoz, & da Silva-Pocinho, 2018).

Results

Confirmatory Factor Analyses

In order to validate the structure of the DJTS, we performed three CFAs, using the maximum-likelihood estimation, with three possible models to determine which one fits better to the data. The first hypothesis is that the data would fit a one-factor model; the second was that of the original version of the scale, that is, that the data would fit a model made up of two correlated factors: Dominant Tactics and Jealous Tactics; and, lastly, the third possible model is that the data would be organized in two factors, Dominant tactics and Jealous Tactics, but in this case, both integrated in a second-order factor (hierarchical model).

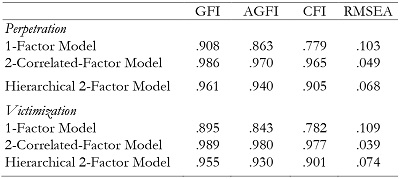

The goodness-of-fit indexes for the three solutions are shown in Table 1. In the models for perpetration, the indexes obtained indicated that the fit was not optimal either for a single-factor model (GFI = .908, and RMSEA = .103) or for the hierarchical two-factor model (GFI = .961, and RMSEA = .068). Likewise, the victimization models also indicated that the fit was not optimal either for a one-factor model (GFI = .895, and RMSEA = .109) or for the hierarchical two-factor model (GFI = .955, and RMSEA = .074).) However, the two-correlated-factor model had the best fit to the data both for perpetration (GFI = .986, and RMSEA = .049) and for victimization (GFI = .989, and RMSEA = .039). In both cases, GFI index was higher than .90, and the RMSEA was below .05, which allows us to conclude that the best model is the the two-correlated-factor proposed by Kasian and Painter (1992) in the original version of the scale. Although some adjustment indexes in the 6 models are acceptable, comparing RMSEA in the 3 models for perpetration and the 3 for victimization, the best adjustment is provided by the two-correlated-factor (see Table 1).

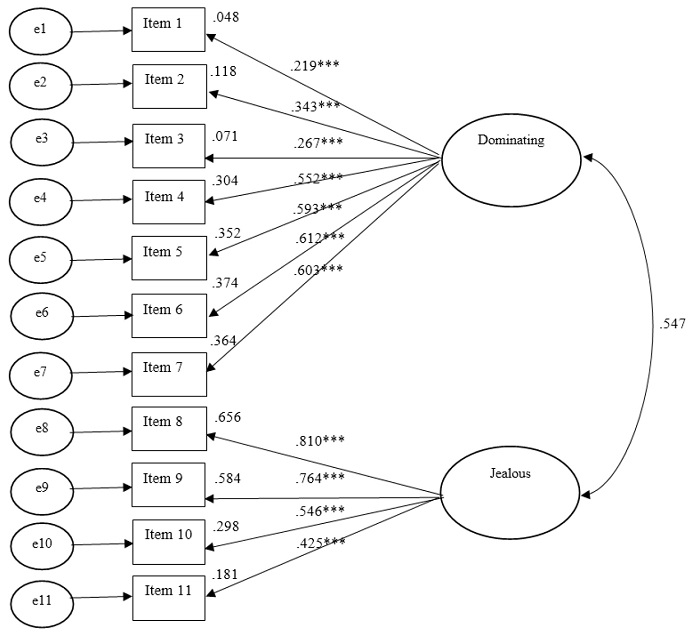

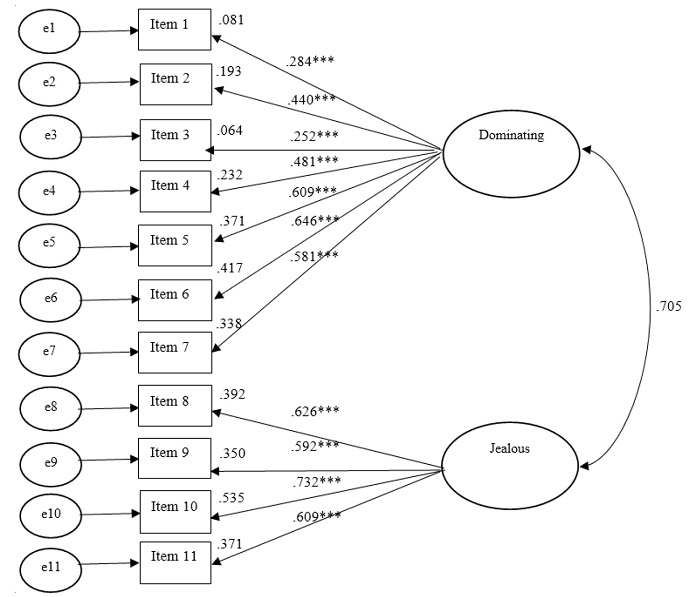

The standardized regression coefficients (standardized factor loadings) and squared multiple correlations are shown in Figure 1 (2-correlated-factor model for perpetration) and Figure 2 (2-correlated-factor model for victimization). The factor loadings of the items on each one of the factors were statistically significant and sufficiently high (> .40), except for Items 1, 2, and 3 in perpetration and Items 1 and 2 in victimization, despite which the structural validity of the two models was not affected.

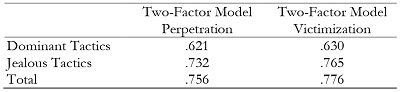

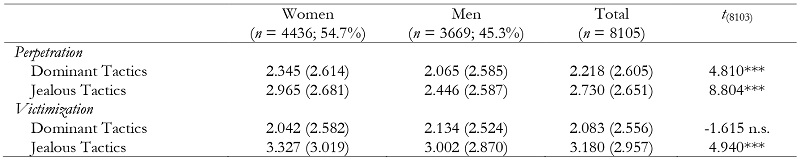

Regarding reliability analysis, it can be observed in Table 2 that the reliability of the scale was good both for perpetration and victimization (Cronbach α = .756 and .776, respectively). The reliability of the Dominant and Jealous Tactics subscales was acceptable (Bagozzi & Yi, 1988), with α-values between .621 and .765, taking into account that they are both made up of a relatively small number of number of items (7 and 4 items, respectively).

Convergent validity

Next, we analyzed the convergent validity of the DJTS by calculating the Pearson correlations between the scale and the scores in Verbal and Physical Aggression measured with the M-CTS. As can be observed in Table 3, all calculated correlations were high and statistically significant, both for perpetration and victimization (p < .001), although the correlations between the two factors of the DJTS and the Verbal Aggression subscale of the M-CTS were higher in comparison with the Physical Aggression subscale.

Known-groups validity

To analyze known groups validity and appraise the capacity of the DJTS to discriminate between different groups

Table 3. Pearson´s Correlations among Dominating and Jealous Tactics Scale and Measures of Verbal and Physical Aggression. Perpetration and Victimization.

Note. DJTS = Dominating and Jealous Tactics Scale; M-CTS = Modified Conflict Tactics Scale; M = mean; SD = standard deviation; α = Cronbach´s Alpha;***p < .001

of participants, we firstly analyzed the relation between age and perpetration and victimization of dominant and jealous tactics and, secondly, the relation between aggression and the sex of the participants in the study.

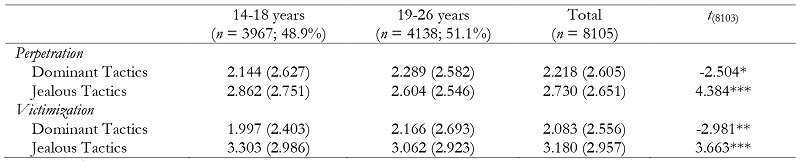

Different studies on dating violence in adolescents and young adults indicate that physical aggression decreases with age, whereas psychological aggression increases, and becomes a key aspect in middle-to-late adolecence (16-17 years), where a maximum peak of physical and sexual aggressive behavior is produced (Fernández, O’Leary, & Muñoz-Rivas, 2014; Foshee et al., 2009). Taking these data into account, in this study, we divided the sample into two age groups: adolescence (14-18 years; 48.9% of the sample) and early adulthood (19-26 years; 51.1% of the sample). The results revealed statistically significant differences as a function of age group in perpetration of dominant, t(8103) = -2.504, p < .05, and jealous tactics, t(8103) = 4.384, p < .001, with the age group of 19- to 26-year-olds using more dominant tactics and the age group of 14- to 18-year-olds using more jealous tactics. Results in victimization were similar, with younger individuals being more frequently victims of jealous tactics, t(8103) = 3.663, p < .001, and older ones, of dominant tactics, t(8103) = -2.981, p < .01 (see Table 4).

Table 4. Means, Standard Deviations and Differences by Age in the Subscales of the Dominating and Jealous Tactics Scale.

Note.*p < .05 **p < .01 ***p < .001

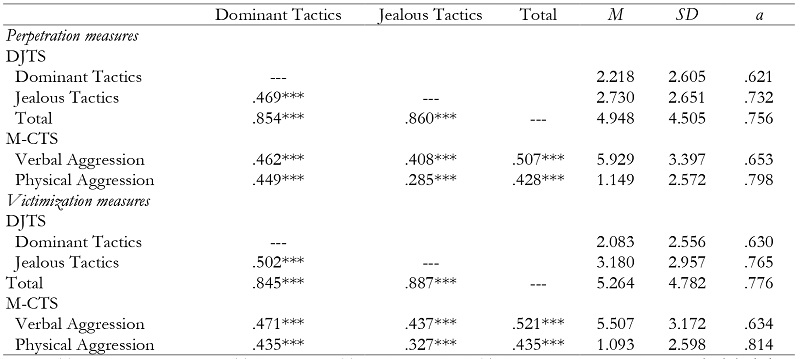

Regarding sex, various studies with this type of samples reveal differences between males and females in the use of dominant and jealous tactics in dating relationships (Muñoz-Rivas et al., 2007b; Orpinas et al., 2012; Ybarra et al., 2016) being women the ones that make the most use of such tactics. The results of the present study indicate that women, compared with men, perpetrate more dominant, t(8103) = 4.810, p < .001, and jealous tactics t(8103) = 8.804, p < .001, and are also more frequently victims of jealous tactics, t(8103) = 4.940, p < .001 (see Table 5).

Discussion

The main goal of this study was to adapt the DJTS (Kasian & Painter, 1992) in a sample of young adults and adolescents of Spain, analyzing the reliability of the scale and its construct validity by means of three methods: confirmatory factor analysis, convergent validity, and known groups validity. In spite of the fact that the DJTS is frequently used to measure dating violence (Cascardi et al., 1999; Muñoz-Rivas et al., 2007b, 2009), no previous investigation has analyzed the structure and the psychometric properties of this scale in Spanish young adults and adolescents. Therefore, we performed CFA with the three possible models that could fit the data: 1-factor model, 2-correlated-factor model, and hierarchical 2-factor model. The 2-correlated-factor model offered the best fit to the data of this study. Thus, the factor structure of the scale coincides with the proposal by Kasian and Painter (1992) in the original study, and is a valid measure to assess dominant and jealous tactics in dating relationships of Spanish young adults and adolescents.

With regard to the reliability of the DJTS, firstly, it could be affected by the number of items in the two subscales: 7 items in Dominant Tactics and 4 in Jealous Tactics. In spite of not being a large number of items, the reliability of the two subscales was acceptable both in the model of perpetration and in that of victimization, with Cronbach alpha values ranging from .621 to .765. The reliability of the total scale of the DJTS was .756 for perpetration and .776 for victimization, very similar results to those obtained in other studies of samples with young adults and adolescents (.72 and .76, respectively) (Cano et al., 1998).

With regard to convergent validity, the two subscales and the total DJTS scale correlated significantly and positively with physical and verbal aggression measured with the M-CTS, which again is in line with findings of other studies (Cascardi et al., 1999). The correlations with verbal aggression were higher, as could be expected from the theoretical viewpoint because dominant and jealous tactics are two forms of psychological violence in dating relationships (O’Leary & Smith Slep, 2003).

Lastly, known groups validity was analyzed in order to determine whether DJTS discriminates between groups of participants according to their age or sex. With regard to age, the results indicate that both perpetration and victimization of dominant and jealous tactics tend to increase with age (Ybarra et al., 2016), with the use of jealous tactics being more frequent in the younger group (14-18 years) whereas dominance is used more frequently as individuals age (19-26 years). Regarding sex, the results again indicate that, in this population sector, the percentage of females who admit using dominant and jealous tactics in their intimate relationships is greater than that of males (Cascardi & Avery-Leaf, 2015; Fernández et al., 2014; Foshee et al., 2009; Hernando, García, & Montilla, 2012; Holditch et al., 2015; Muñoz-Rivas et al., 2007b; Orpinas et al., 2012; Ybarra et al., 2016).

To conclude, the results of this study confirm the DJTS as a valid and reliable instrument for use in research of dating violence, with different goals: (a) to measure perpetration and victimization of this type of behaviors, (b) to orient prevention programs on this issue more precisely, (c) to assess the efficacy of different intervention programs of dating violence with this population. Nevertheless, in view of future research, it would be interesting to explore some additional psychometric aspects (test-retest reliability and predictive validity), as well as the extent to which the responses are affected by participants' social desirability.