INTRODUCTION

Modern Judo has evolved from its Japanese martial roots, to the point of allowing real fighting, both in training and competition scenarios. We ground this investigation in features of modern competitive Judo, namely: (a) few competitions over the season and relatively long periods of preparation, depending however on the athlete's level of competition; (b) largely an amateur sport, especially at the bottom levels of competition, although a slight progress is becoming evident in the past years, towards some degree of professionalization at the upper levels of competition - e.g., introducing prize moneys; (c) despite Judo being an individual sport, it is impossible for a competitor to carry out specific training without partners, which explains the attendance of athletes at training camps with rival competitors from other Clubs or Nations; (d) it is a contact sport with one-on-one combat simultaneously demanding decision-making, due to its uncertain and unpredictable nature (Rogowska & Kuśnierz, 2012), requiring technical resourcefulness and according to Franchini, Del Vecchio, Matsushigue, and Artioli (2011) a mixture of physiological qualities; (e) during fights verbal communication between coach and athlete is one-sided, since only the coach is allowed to talk, and usually limited to scarce seconds due to the refereeing rules; (f) at the top level competition, towards Olympic qualification, one single mistake or a split-second distraction is enough to end a fight (Ziv & Lidor, 2013) and be eliminated of a competition, since a second chance in repechage is only allowed to athletes defeated at quarter-finals or semi-finals.

Outstanding competitors make potential into skill (Butt, Weinberg, & Culp, 2010) and are able to perform at the best of their possibilities, not only tactical-technically and physically speaking, but also psychologically. There is a considerable scientific evidence base, which asserts the determinant role of psychological aspects in the performance of elite athletes (Gould, Dieffenbach, & Moffett, 2002; MacNamara, Button, & Collins, 2010). Mental toughness allows athletes to express their training competence consistently in evaluation moments such as competition (Gucciardi, Gordon, & Dimmock, 2008). A landmark study in sport's mental toughness defined it as a natural or developed psychological edge, presenting competitors with more advanced and consistent skills in terms of determination, focus, confidence and control under pressure, as they coped with all the demands that top level sport places on athletes (Jones, Hanton, & Connaughton, 2002). Coulter, Mallett, & Gucciardi (2010) have defined the construct differently, without making comparison with other competitors' psychological skills:

Mental toughness is the presence of some or the entire collection of experientially developed and inherent values, attitudes, emotions, cognitions and behaviours that influence the way in which an individual approaches, responds to and appraises both negatively and positively construed pressures, challenges and adversities to consistently achieve his or her goals (p. 715).

So when competitors face tough demands, mental toughness seems to emerge as a decisive edge for success. Against similar levels of tactical-technical skill and physical preparation among competitors, it is plausible to consider that mental toughness distinguishes between good athletes and those who achieve excellence (Gucciardi et al., 2008).

However, Andersen (2011) raises the debate concerning the conceptualization of the construct, asking if mental toughness may not simply be a slogan that sells the image of a perfect and thus unrealistic athlete. Furthermore, it is reasonable to accept that high performance in sports does not depend merely on psychological attributes, but also on sport knowledge (technique, tactic, strategy) and physiological or physical variables. Such as we accept that physical talent alone does not guarantee success (Gucciardi et al., 2008), neither do psychological aptitude by itself. Therefore, although mental toughness has been to some degree conceptually associated with competition outcome (Jones et al., 2002, 2007), we consider that a mentally tough competitor can fail to achieve top level results due to other non-psychological performance variables. This is exactly the case in Judo, being a complex sport. In fact, to reach top-level competition in Judo, an array of factors must be developed in athletes, ranging from technical and tactical skills to psychological dimensions and physiological variables (Santos, Fernández-Río, Almansba, Sterkowicz, & Callan, 2015). In this context, it is reasonable to accept that being a mentally tough judoka may be a competitive edge. Otherwise, it will be one more weakness to be explored by the opponents.

According to Gucciardi, Hanton, Gordon, Mallett, & Temby (2014), of all mental toughness research papers, chapters or conference presentations which included mental toughness in its title or topic, over 95% of the publications have emerged since the end of the twentieth century. In recent years research developments on mental toughness were too evident, through both qualitative and quantitative methods. Various general attributes of mental toughness have already been identified in multisport researches (Butt et al, 2010; Jones et al., 2002, 2007; Weinberg, Butt, & Culp, 2011). Beyond that, several studies have already focused on some Sport Psychology issues applied to Judo, including self-esteem, self-efficacy, self-confidence, trait and state anxiety, somatic and cognitive anxiety, intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, perceived precompetitive stress, coping strategies and styles of coping with stress (e.g., Amoedo & Juste, 2016; Gillet, Vallerand, Amoura, & Baldes, 2010; Interdonato, Miarka, & Franchini, 2013; Rogowska & Kuśnierz, 2012). However, no previous research was found investigating mental toughness in Judo. Even despite understandings that pointed out slight variants within mental toughness behavioural manifestations, according to the specific mindset required in each sport (Bull, Shambrook, James, & Brooks, 2005; Jones, Hanton, & Connaughton, 2007). In fact, being aware of that, several authors have inquired about the psychological qualities of sport-specific mental toughness, including in sports such as Cricket (e.g., Gucciardi & Gordon, 2009), Soccer (e.g., Cook, Crust, Littlewood, Nesti, & Allen-Collinson, 2014), Australian Football (Gucciardi et al., 2008) and Ultramarathon (Jaeschke, Sachs, & Dieffenbach, 2016). Besides that, following the reasoning of Gucciardi, Gordon, and Dimmock (2009), some authors underpinned their researches on the Personal Construct Psychology theory (Kelly, 1991) in an attempt to better qualitatively understand the construct of mental toughness.

Knowing that mental toughness attributes within sport-specific boundaries have been investigated in current literature, we undertook a qualitative approach, considering the absence of any research on mental toughness within a population of Judo competitors. Thereby, in line with previous single-sport qualitative research, the purpose of this study was to explore perceptions of athletes, identifying and conceptualizing mental toughness attributes within the specificity of Olympic Judo. Through which we also deal with the lack of qualitative studies focused on Judo as highlighted by Ziv and Lidor (2013), while aiming at gaining an in-depth understanding of the judokas' perspective. Furthermore, considering that some sport-specific qualitative researches have already contributed with new attributes to the extant literature (e.g., Driska, Kamphoff, & Armentrout, 2012), we aim to do the same through this study in Judo, due to the sport's particular features at the modern competitive setting. Hence, we expect to collect some evidence beyond the sport-specific characteristics resulting from previous single-sport studies.

Following the reasoning of recent literature (cf. Jaeschke et al., 2016), we included participants with different levels of involvement. Cook et al. (2014), on their turn, although valuing research within the elites, considered that “different sports, different settings, different levels of competition, and different participants are likely to produce different results”. Thus, in order to frame a wide understanding of mental toughness in this particular sport, we collected perceptions of Judo athletes with different levels of competitive achievement (i.e., podium results at regional, national and international levels of competition). Along these lines we expanded our study sample beyond an elite group of medallists at Olympics and/or world and continental championships. By doing so we avoided the assumption, seen by some authors as a limitation in studies, that elite competitors are invariably the only ones either mentally tough (Crust, 2008) or knowledgeable about the subject. Considering, therefore, that mental toughness should not only be studied in elite or super elite athletes, but also examined in amateurs who did not reach competitive top level success (Gucciardi, Gordon, & Dimmock, 2009).

METHOD

Participants

In order to assemble a holistic insight into the subcultural domain of competitive Judo, we used a purposive sampling technique (Patton, 2002). Given the extent of the interview protocol and the length and depth of the conducted interviews, a total of 12 Judo athletes were interviewed in person once by the same researcher. The first author invited the athletes directly, either personally or by phone, to anonymously take part in the research, explaining its purpose.

As the heterogeneous sampling was meant to gain the desired richness in the collected data, we selected a sample of Judo athletes with different levels of competitive results, within the population of Portuguese Judo competitors. Thus, the non-elite group (NEG) was comprised of medallist judokas in regional championships, who have never had a medal at the Portuguese national championships. In the sub-elite group (SEG) were Judo competitors who had won at least a medal at the senior or junior national championships, but had not accomplished any podium result in the European and world championships neither at the Olympics. In contrast, medallists at the Olympics and/or at world and European championships, including both senior and junior age groups, established the elite group (EG). From the EG, only one athlete did not have Olympic participation.

Our sample included four non-elite, four sub-elite and four elite judo athletes, comprising a total of three females and nine males. Only two from the EG were former athletes while the remaining ten were competitors in active. The athletes' ages ranged between 17-40 years, with an average of 20.8 ± 3.2 years (M ± SD) for the NEG, 20.8 ± 3.3 years for the SEG and 28.5 ± 9.7 years for the EG. Experience of Judo practice ranged between 9-21 years, with an average of 11.3 ± 2.2 years for the NEG, 14.5 ± 5.0 years for the SEG and 18.3 ± 3.1 years for the EG. Considering competitive experience, athletes competed nationally between 5 to 17 years, for an average of 7.0 ± 1.8 years for the NEG, 7.5 ± 3.1 years for the SEG and 11.8 ± 4.1 years for the EG. As for international competitive experience it ranged from 0 to 16 years, in an average of 1.3 ± 1.9 years for the NEG, 5.0 ± 4.2 years for the SEG and 9.8 ± 4.9 years for the EG.

Instrument

In the context of the exploratory nature of our endeavour, we conducted individual, semi-structured interviews. In addition to exploring the participants' understanding, the semi-structured interview was identified as a frequent qualitative method used to investigate mental toughness in sport (Jaeschke et al., 2016; Thelwell et al., 2005). Prior to that, two pilot interviews, conducted with Brazilian judokas disconnected from the study, served as training for the interviewer. These pilot interviews took place, in order to verify the relevance of the open-ended questions within the interview guide and so that athlete's perceptions about sport-specific mental toughness attributes in Judo could be extensively and deeply collected. No subsequent changes were made to the interview protocol.

Participants were given a copy of the interview guide, sent by e-mail, one week prior to the date scheduled for the face-to-face interview, alongside with explanations regarding the nature and purpose of the study, so that they would had the chance to get familiar with the questions. Before being interviewed, all the participants signed a consent form authorizing for data audio recording. Ethical approval for this investigation was also granted from the relevant committee at the interviewer's University.

For the elaboration of the interview protocol we took in consideration principles from Personal Construct Psychology (PCP), mainly sociality and dichotomy corollaries (Kelly, 1991), thus following previous applied research to mental toughness (Coulter et al., 2010). Through the sociality corollary applied to our interview protocol the interviewees sought to perceive the vision that other athletes have of their surrounding world (cf. Gucciardi & Gordon, 2008). As for the dichotomy corollary it was useful since athletes experienced at lower levels of competition, were likely to understand the concept of mental toughness in light of what it is not. The interview guide comprised five sections (i.e., conceptual definition, situations, characteristics of mental toughness, athlete's introspection and mental toughness trainability) and consisted of 17 questions, seeking to collect not only but also the participants conceptual understanding of mental toughness (e.g., can you summarize in a definition what describes your understanding about mental toughness in Judo?), their perceptions about the attributes required in competitive Judo (e.g., which attributes of mental toughness allow to differentiate between the mentally stronger and the least strong athletes?) and additionally requesting the judoka for an introspection (e.g., what mental toughness characteristics do you possess and on which ones do you feel that you need to progress?). During each interview, meaningful notes were taken by the interviewer. That allowed follow-up questions to be timely addressed as needed, including clarification probes to make clear any dubious expressions or jargon presented by participants, elaboration probes for gathering more detailed information and, seldom, counterfactual questions. Non-verbal and short verbal cues were also employed, encouraging interviewees to keep sharing thoughts.

Interviews took place mainly at different Club facilities' and, alternatively, at public locations of each athlete's choice. All interviews started by collecting demographic and sporting data of the athlete. In all conducted interviews, the first author and interviewer adopted a neutral stance, questing for elaboration without influencing participants' points of view. All interviews were conducted in the native Language of the judokas (Portuguese) and took in average 60 minutes, ranging from 25 to 105 minutes in length. The full content was digitally audio recorded and afterwards transcribed verbatim, generating 148 single-spaced pages of typed transcript with one inch of margins.

Data analysis

The 12 interview transcripts were individually read and listened to by three members of the research team, gaining an overall view of the data. In order to reach the goals of this research, inductive content analysis was the research technique employed by our investigation team. The analytic process of uncovering and delimitate concepts through “open coding” (Corbin & Strauss, 1998, 2008) did not leave any text segment uncoded. Qualitative research software NVivo11 was used to categorize and manage the vast data collected. Categories naturally arose based upon raw data and, being mutually exclusive, did not overlap with each other, since consistent definitions were given, differences between categories were attained and multiple reviews were made. Properties and dimensions of each category were developed in line with key methodological aspects underlined by Corbin and Strauss (2008). Inferences were made towards the conceptualization of a mental toughness overview specific to the sport of Judo.

The interviewer, known in the sport, was himself a Judo practitioner for almost 27 years and a former athlete during 14 years. The fact that the interviewer was known in the National Judo community helped him in building rapport with the interviewees, thus assuring an informal climate prone to honest conversation between each of the participants. The other members of the investigation team were not knowledgeable in Judo, but were experienced researchers in qualitative methods.

Not infrequently it was easy for interviewees to explain mental toughness characteristics based on their opposites. For example, self-doubt described by athletes (definitely not being a mental toughness feature) was interpreted by the research team as being an opposite attribute of self-confidence, interestingly corroborating previous investigations (Coulter et al., 2010; Gucciardi et al., 2008). Indeed, the coding process of the raw data benefited from the dichotomy corollary of Kelly's (1991) PCP theory, thus overcoming, to some extent, a “notable limitation of previous research on mental toughness” (Gucciardi & Gordon, 2008). Codification was done by the first author, making inferences and developing theory based on the collected data. Trustworthiness through investigator triangulation (Patton, 2002) was later assured in the coding process and along inductive analysis, taking in two more members of the research team experienced in this qualitative technique, but not involved in the literature review for the study. The very few inconsistencies that arose among the three researchers, if not harmonized between all, were settled by the main author, valuing his familiarity with the sport and its competitive setting.

RESULTS

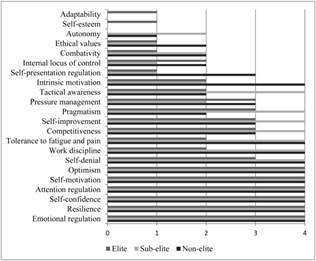

Figure 1 presents our findings in terms of mental toughness characteristics and its frequency among the sample (n = 12), according to the athletes' different levels of achievement (elite, sub-elite and non-elite). In the text below, each of the 22 mental toughness attributes is described and presented in descending order of frequency through which it was mentioned by the athletes. All judokas cited are identified in reference to their respective achievement level. We have noticed that six of those characteristics arose through the whole sample and three did not emerge through all achievement levels.

Table 1 presents a summary conceptual description for each attribute phrased with words of the judokas, indicating the frequency that each mental toughness characteristic was mentioned by the participants of the sample.

Emotional regulation. This attribute resembles a state of calmness, as explained by one of our Olympic athletes interviewed: “Within the winning athletes, world and Olympic champions, for some it's just another day at the office.” It represents the efficient and effective performance of the physical body irrespective of the contextual demands. That is, to control useless thoughts and negative emotions (e.g., anger, fear, anxiety), so that they do not interfere negatively while performing (e.g., avoiding choking under pressure), but rather favorably to the competitor. For instance, one sub-elite athlete referred “the anger of being behind result” as an underlying emotional weakness to tackle, in that it caused him to do “irrational offensive actions” during the fights, resulting in undesirable competitive outcomes.

Resilience. The concept emerges as a positive adaptation in the presence of adversity, either being mistakes or very difficult and hard to overcome situations. It consists in suffering, persisting and surpassing adversities, instead of giving up easily or letting go quickly as it will be the case with the more fragile judokas, noticed one sub-elite athlete: “The psychologically weak judoka simply does not insist on overcoming difficulties.” The contrasting reality is put into context by another sub-elite competitor:

Once, in a competition in Poland, I was losing until a few seconds from the end. And I kept putting pressure on the athlete, trying to see if he made any mistake and trying to do the technique I wanted to do. And even in the last second I threw him with a [name of Judo technique] and I scored a [highest advantage which ends a fight]. I was able to be strong enough psychologically to keep trying until the end and trying to find solutions to the end. And do not let the fact, that I was losing and few seconds were remaining, affect me.

Moreover, winning when an athlete is not at his best level of preparation was depicted as an example of resilient behaviour, where the athlete endures any low moments in either physiological or tactical conditioning and still performs effectively in competition. Resilience stood out as relevant also when judokas were struggling through a bad training day, being especially evident when in the presence of fatigue and when an athlete was feeling unable to throw anyone during simulated practice of competition fighting (i.e., during randori).

Self-confidence. It consists in believing that one can perform successfully in a given situation and has the abilities that will lead him to success. In a more specific sense, it also covers self-efficacy in decision-making during Judo bouts, which requires tactical-technical knowledge. An example of that was given by an elite competitor:

Has confidence in his capacities, so that in moments of competition accompanies one hundred percent a decision making. That is, when we make a technical-tactical decision, to believe a hundred percent, not to hesitate - whether to do or not to do, whether to risk, whether I am strong or I am weak, whether I am able to throw.

Based on our findings, the opposite of being confident was doubt, hesitation, insecurity about oneself. Moreover, having the impression that no task has been left undone and that preparation met the highest standards of demand is an important part of being self-confident, because, consequently, this nurtures a strong belief in victory. However, an athlete's confidence is also dependent on competitive results, as well explained by one sub-elite athlete: “It is not enough to train at a high level and do many intense training sessions. One must also have results, materializing the athlete's training. Otherwise he may begin to lose confidence.”

Attentional regulation. Our results underlined as crucial the ability to constantly shift the attentional focus on whatever is essential in every moment, within the fight itself and also outside the competition day, throughout practice and daily routines. A practical example was given by one sub-elite athlete:

Be focused on the work that I am doing, do not let me be distracted. For example, we have finished a task, we go to drink water and I do not get into conversation with colleagues or let myself be distracted from the moment that is the training.

An athlete must be able to adapt his focus accordingly, in order to overcome the multiple and ever-changing demands he faces, particularly while fighting: “When I go to the randoris I am concentrated. I'm thinking about what I'm going to do. How am I going to hold, the attack I'm going to make, how I want to throw or not.”

Interestingly, our accounts indicated that proper concentration allows an efficient emotional regulation. For instance, if a thought is useless, mentally tough judokas simply don't give it any attention. Instead, they focus at the tactical and strategic variables concerning the “here” and “now” of the fight. For the athlete is more productive to concentrate at the sport-specific decision making involved in a Judo bout. Rather than losing his focus in subjects or thoughts with no practical relevance (e.g., lack of luck in the draw, the high competitive level of the opponent in the first contest, bad referee call). In the words of a non-elite athlete, a mentally tough judoka “is someone who shows… coldness, who does not let himself get out of control with the interference of the public and other distractions, which are inherent in a combat.”

Self-motivation. This concept consists of having self-initiative and the will to define its own goals: “A strong judoka is one who aspires to reach the world championships and reach the Olympic Games and make good results.” It is about being determined, even stubborn and obsessed in struggling to achieve ambitions and objectives, including performance goals, towards which the athlete directs his energies and actions. Poorly defined goals may compromise intense training exercises, as explained by one non-elite competitor: “When it starts to hurt, if the person is training aimlessly, it will result in letting himself down.”

Optimism. Having a belief that things will work out well is a quality of the mentally tough athletes. One elite female judoka gave us a good example in the training context: “Today's training is not what I was expecting, but tomorrow will be.” Optimistic athletes go by without worries about coming events, emphasizing the need to live in the present. They do not fear failure in general neither do they feed expectations of failure about the future. One elite athlete elaborated well on this notion, narrating a short story of driving abroad with two athletes and how differently one and another shared their thoughts on the upcoming event: “In an approach to a competition, the negative athlete begins to predict everything that can go wrong. The most positive athlete will focus on finding solutions and opportunities.”

Self-denial. This concept was reported as being an inherent attribute evident across the toughest competitors: “… after a strong workout at night, you need to get up early in the morning to go to school. It costs, because I'm tired of my muscles, I'm sleepy and it takes a lot of effort to get up.” Therefore, for an athlete to acknowledge self-denial he must be willing to sacrifice his personal and social life, his own comfort and many of the comforts of contemporary life, in favor of its progression and strengthening as a competitor. Sometimes even an athlete's personal preferences have to be sacrificed, like it was revealed by one sub-elite judoka: “Sometimes I do not have much patience to do weight training, but you have to do it.” This demonstrates the importance of making certain sacrifices so that Judo is given priority.

Work discipline. According to the judokas interviewed, being disciplined with tasks enables one to fulfill goals according to its level of priority (i.e., first things first). Thus, discipline regarding diet and social lifestyle was emphasised. Though being disciplined is mainly as simple as completing the work that is supposed to do and to seriously undertake the tasks that they are assigned to by coaches. This idea was interestingly elaborated by one sub-elite athlete: “Going to the training session and training [effectively] are two completely different things. Going to training is the characteristic of less strong judokas… He went. He didn't do ‘anything'. But he went there.”

Tolerance to fatigue and to physical pain. This phrase summarizes the main idea of the concept: “An athlete who trains to compete has a constant struggle with pain.” A mentally tough competitor must withstand situations of injury related pain and states of discomfort and fatigue, either accumulated over time or due to intense occasional demands, both in training and competition.

Competitiveness. It is about aiming to be the best at the sport. A competitive judoka has the will to win and to challenge oneself, in order to become the best at the sport. In training, for instance, this means “being the one who projects the most and falls the least”. Hating to lose was also evident for this concept.

Self-improvement. This comprises a set of performance dimensions, such as physical, physiological, technical, decisional variables. It was mainly related to athletic progression, level up through loyal practice. In the words of a non-elite participant, “a judoka is always learning.” The concept included also an attitude to interpret learning and training challenges as opportunities, by which athletes fostered their own athletic growth and knowledge of the sport.

Pragmatic. A large number of our studied athletes implied on the importance of realistically identifying what has to be done to succeed and simply doing it for every situation, even if that implies having to admit any transient weaknesses. “A stronger judoka does not even complain, he simply complies”, because, as it was stated by another athlete, “…what has to be done, has to be done.” Pragmatic competitors are action-oriented and hold “the ability to simplify adversity”, instead of contributing to amplify and problematize already challenging circumstances. Sometimes, harsh behaviours can be confused with egoism, since pragmatic judokas prioritize their own interests as it was well exemplified by one female sub-elite athlete, when competing alongside teammates of the National Team: “Although I have teammates who also compete, I'm first.”

Pressure management. The mentally stronger competitors are able to deal with various potentially stressful situations and deliver the desirable outcome, despite being under pressure. Major pressures perceived by judokas came from the need to obtain predefined results in competition. In the words of a non-elite judoka, handling pressure during a fight against a superior opponent can be as simple as managing his thoughts: “... I will not fight against an Olympic champion; I will fight against a judoka just like me.” Moreover, as stated by an elite athlete, even a remark or comment someone says to a competitor, if not well managed, may result in pressure and can turn out to be stressful for a mentally weaker judoka: “Interference can be someone telling me that I will not qualify for the Olympic Games.”

Tactical awareness. This was emphasized by judokas of all levels of achievement as an attribute that consisted in the ability to make good tactical decisions. Thus, related to the sport tactical-technical specificity and as a sport skill based upon decision-making that allowed an athlete, at some extent, to control the unfolding of a Judo fight through superior tactics. A non-elite judoka elaborated well on the concept: “In the moment that he noticed a single carelessness from the opponent, he scored [the maximum advantage in Judo] and won the final.”

Intrinsic motivation. The assertion of a sub-elite athlete makes the conceptualization of this category unequivocal: “I think that when a judoka is truly passionate about the sport he turns out to be psychologically stronger…” It rests simply in an intense passion for Judo, enjoying the fight itself due to the satisfaction they draw from it. Some athletes also considered the pleasure in practicing and perfecting the game of Judo.

Self-presentation regulation. The convenient physical expression of thoughts and emotions lies in this quality elaborated by judokas. Whereas adopting a rough appearance is the visible part of actually being mentally tough, body language also sends a message to the opponents of being in control, especially when facial expressions cannot be interpreted. Indeed, one interviewee gave the example of the 2016 Olympic champion at the under 73 kg weight category that during competition was not seen frowning or smiling till the last fight was over. Moreover, this quality can assist in strategically hiding casual weaknesses (e.g., fatigue, injury) as it was explained by a non-elite judoka: “An athlete who is injured needs to demonstrate mental toughness to be able to stay in the fight without showing the opponent that weakness.”

Internal locus of control. This concept was conveyed as a perception of control over the unfolding and outcome of certain events that typify the life of the Judo competitor. It is also about assuming responsibilities for one's bad results. A non-elite athlete elaborated on that: “Is to accept the error, to accept that we were insufficient in that moment and that it was our fault, not throwing it away [the guilt] like a hot potato.” Contrariwise, said a sub-elite participant, “an athlete who is psychologically not strong is that type of judoka which always gives excuses…”, as a mentally tough competitor does not make excuses neither tends to attribute faults to external causes. Besides, if some aspect of competition is clearly out of the athlete's control, he simply does not direct his focus to it.

Combativity. It was presented as a vigorous style of fighting, physically speaking, but while maintaining tactical sense. It rests in seeking to dominate the opponent, restrict their actions in the struggle through a physically intense, rather aggressive attitude towards fighting, constantly pressing the opponent's game. This was evident in the words of a sub-elite athlete: “Aggressive in the sense of taking the initiative. In competition we go towards him. We do not allow the opponent to grip [first] or bend us.”

Ethical values. These were identified in athletes as a firm conduct based upon humble, respectful and hardworking morals. In reference to doping one elite athlete elaborated on this concept: “I believe there are other sports in which the pressure is so great that athletes may tend to take shortcuts, if their character and values are not strong.”

Autonomy. This quality was pointed out in relation to one's athletic progression, either directly in practice or any other relevant sport career aspects that a competitor may independently decide on, apart from coach guidance. While according to one sub-elite athlete “the psychologically weak [athlete] can only follow the coach's instructions.”

Self-esteem. This was one of the only two mental toughness concepts solely referred by a single judoka, stressing how important was for the athlete to feel good with himself and in the context of his relationship with significant others. This elite athlete explained the concept as “the position of oneself before other people; how we feel about everything.”

Adaptability. Interestingly, this concept was appointed only by the same elite athlete that reported self-esteem. To become over time comfortable throughout defying sport-specific circumstances (e.g., dieting and losing weight, training abroad) was described as a quality inherent to the mentally tough judokas. The concept was based on the ability to progressively transform one's habits and thus adapt to the demands of the sport, to the point of accepting and normalizing certain initially uncomfortable situations. This phrase summarizes the concept: “… it's not just a stressful situation that I'm waiting for it to end, but it is something that I have already internalized as a standard of living.”

DISCUSSION

Elite athletes are expected to seek to learn more about popular understandings of mental toughness than their lower achievement counterparts (Gucciardi et al., 2008). Yet studies only focus at top level competitors. This trend was seen as a limitation by Cook et al. (2014), which we addressed through this research. Thus, our heterogeneous sample, composed of athletes from different levels of achievement and both genders, allowed us a more genuine and deeper understanding of mental toughness, in the particular context of competitive Judo, from bottom to the top level competitive involvement.

Considering Portugal's level at the international competitive setting, being able to interview three Portuguese Olympic judokas, including a medallist, was a strength of our research. The fact that we conducted extensive and in-depth interviews was also a strong point of our research. However, having interviewed once each one of the 12 athletes may stand out as a limitation in our study, since it may have hindered our goal to obtain all the scope of understanding truly possessed by each athlete. Thus, some minor details may have escaped our comprehension of mental toughness in Judo. That may have been the case when two attributes (i.e., adaptability and self-esteem) were accounted by one single elite athlete, across a sample of 12 competitors. However, those attributes were conveyed by the only Olympic medallist of our sample.

We aimed at identifying the distinctive nature of being mentally tough in Judo. Thus, considering literature which addressed sport-specific mental toughness attributes (Bull et al., 2005; Cook et al., 2014; Gucciardi et al., 2008; Jaeschke et al., 2016; Thelwell et al., 2005), large conceptual similarities were found between Judo and those four sports studied in the four single-sport publications mentioned above. Identical matches were also detected relating Judo attributes of mental toughness with results from multisport researches on mental toughness (Jones et al., 2007) and over the importance of psychological qualities in elite sport (Gould et al., 2002; MacNamara et al., 2010).

Nevertheless, some differences in terminology were identified, since other labels were used while reporting to the same attributes conceptualized in our study (e.g., controlling emotions; perseverance; self-belief; concentration and focus; self-set challenging targets; sacrifices; work ethic; physical toughness; handling pressure; sport intelligence; accountability; independence). Along these lines, differences on our results in reference to extant literature are discussed below either being subtle ones or more pronounced. Accordingly, seven conceptual categories arising from our data are considered one by one.

Optimism. No apparent reference to optimism as a mental toughness attribute was found in English Cricket (Bull et al., 2005) neither in British Soccer (Thelwell et al., 2005) and neither in Australian Football (Gucciardi et al., 2008). Contrary to that, research in Australian Soccer identified “optimism” among an extensive list of mental toughness elements and within an higher order attribute labelled “tough attitude” (Coulter et al., 2010). Conceptually, our definition of optimism overlapped the one given by these authors (i.e., to “have a hopeful outlook that the future will be positive and will present with it opportunity”). Interestingly, in a sample of Uruguayan judokas, low level of optimism was found to be correlated with burnout symptomatology (Reche García, Tutte Vallarino, & Ortín Montero, 2014).

Self-improvement. In the pioneer work of Jones et al. (2002), there is no direct mention to self-improvement as a mental toughness attribute. Contrariwise, according to Australian Football coaches, the opposite pole of “determination” was “being easily satisfied with mediocrity” (Gucciardi et al., 2008). Conceptually, this constitutes an attribute partially related with the self-improvement mindset portrayed in our research, by which judokas supposedly would be able to develop their perceived competence. Indeed, those findings concerning this attribute appear to be aligned with the human need of competence as proposed in the self-determination theory conceptualized by Ryan and Deci (2000), since dissatisfaction against mediocrity is likely to foster competence and, therefore, framing a self-improvement mindset. Yet, comparing our results to a recent study conducted by Cook et al. (2014) in an English Premier League Soccer Academy, the “commitment to excellence” mindset appears to be a far more evident conceptual overlap, but only in what it was related to progression, learning and improvement on weaknesses. Since having the “highest working rate and work ethic” and “pushing physical limits”, two qualities which these authors subordinated to “commitment to excellence”, appear to be conceptually different from judokas' notion of self-improvement. Besides, the equivalents of both qualities in our study were, respectively, work discipline and tolerance to fatigue and pain. Indeed, at least in Judo, one can push his physical limits (e.g., losing extra weight to fit in a competition category; see Sitch & Day, 2015) without really searching for excellence. The same logic can be employed in relation to work discipline, as an athlete can exhibit a high work rate to simply recover from an injury or to maintain his already acquired top level technical abilities. If that still is considered to be commitment to excellence, then that separates it from the learning attitude clearly underlying self-improvement found in Judo. However, our results were conceptually coincident with the “exploit learning opportunities” quality found in Cricket, explained in terms of “a clear desire to use learning opportunities and keep learning” (Bull et al., 2005). Interestingly, the scarce available sport-specific literature on this topic suggested that increases in self-perception of competence were more likely to occur from task-oriented motivational climates among female judokas than in male Judo athletes (Ortega, et al., 2017). Moreover, in general terms, Gyomber, Kovacs, & Lenart (2015) particularly highlighted male sportsmen due to their hard work capacity to improve on skills.

Pragmatism. Cricket presented subconcepts of the pragmatism identified in our judokas. One of those was “honest self-appraisal” by which cricketers acknowledged their strengths and limitations (Bull et al., 2005), in a way we may qualify as pragmatic, realistic and harsh. The other overlapping subconcept with the pragmatism of our judokas was the “maintain self-focus” attribute referred in the same study conducted in Cricket. Likewise, some judokas in our study stressed the importance of being self-centered in their own performance. Another quality that appears to be partially encapsulated in our judokas' pragmatism was previously reported among players of Australian Football, namely, the characteristic “positivity” in the sense of focusing on what can be done (Gucciardi et al., 2008). The same authors also reported “self-awareness” amongst footballers, giving it the same meaning of "honest self-appraisal" above mentioned in the cricketers. Of all three aforementioned pragmatism subconcepts, this last one was the only which was transversal to all sports here analysed, thus signalling slightly divergent conceptual understandings between sports.

Self-presentation regulation. Strategies by which athletes self-present to others are seen as having functional implications in regulating both performance (e.g., concentration) and emotions (e.g., anxiety), that if trained intentionally may be developed into deliberate behaviours rather than spontaneous (Hackfort & Schlattmann, 2002). These authors contrasted, for example, between a figure skater whose expressive aspects are a part of explicit performance requirements and a boxer whose presentation and staring conveys useful fight meanings, in an attempt perhaps to destabilise his opponent. According to our results, during a Judo fight, being able to not express any kind of emotions through facial expressions and to express no other message than the control over the situation through body language is regarded as a characteristic only within reach of the mentally stronger competitors. Our finding is reinforced by Hackfort and Schlattmann (2002), who considered that athletes expressed or concealed their emotions as well as demonstrated emotions actually not being experienced. The kind of emotionally neutral self-presentation showed by judokas that may unsettle weaker opponents may be related with findings obtained in Soccer, stating importance in “having a presence that affects opponents” (Thelwell et al., 2005). Ultimately, self-presentation may assign a psychological dimension to the task of establishing a strategy for a fight, that is beyond its obvious tactical essence.

Combativity. Cricketers reported that a strong physical condition of the body was a source of self-confidence (Bull et al., 2005). In the case of judokas, we may also consider “feeding-off physical condition” as a vital part of combativity during fights. Nevertheless, conceptually, combativity goes beyond mere good physical or physiological conditioning. Indeed, combativity was nowhere to be found in a sport like Ultramarathon where pushing physical limits is crucial (cf. Jaeschke et al., 2016). On the other hand, the Soccer attribute of “wanting the ball at all times (when playing well and not so well)” (Thelwell et al., 2005) seems to be more related with the physically intense and somehow aggressive style of fighting that combative judokas embody. Despite the aforementioned wording differences between Soccer and Judo, the essence of the two sport-specific concepts appears to be shared. That is, both attributes are based on dominating the game, its pace and direction, physically speaking, without neglecting its tactical sense. In support of our results, Escobar-Molina, Courel, Franchini, Femia, & Stankovic (2014) had already highlighted combativity as crucial in order to avoid receiving penalties during a fight. Although behaviours embodying combativity are suggested to be rather peculiar to Judo, this attribute is expected to be evident in other combat sports.

Aiming at a “greater specificity in tailoring interventions” (Crust, 2007), the knowledge on a peculiar attribute of mental toughness found amongst judokas (i.e., combativity) becomes of utmost importance. Some caution is however convenient, because fighting styles may vary according to the culture of the country where Judo is practiced, despite the rules being the same worldwide. If training methods employed by elite Judo coaches were found to be influenced a lot by the coach's sport culture (Santos et al., 2015), particular subcultural domains can also be expected to exert influence over the athletes' fighting styles. For instance, in general the Japanese judokas are traditionally known for their overall technical efficiency, the French judokas gained fame for emphasizing tactics and the Georgians are recognized by their physical power and aggressive fighting style. Furthermore, aggressiveness in young Spanish male judokas with higher competitive achievements was found to be greater than that of their lower achievement counterparts (Suay, et al., 1996). According to these authors, aggressive behavior was also higher among judokas with more years of Judo practice, suggesting influence of competitive involvement in the development of aggressive behavior. Overall, this raises discussion about the importance of aggressive attitude towards fighting which characterized, partially, combativity in our judokas. Thus, further research on the concept of combativity is of interest in Judo and also in different combat sports.

Self-esteem. The concept appears as a novelty in the literature of mental toughness in sport. Nonetheless, the positive and moderated correlation that has been established between Spanish judokas' self-esteem and their competitive results (Amoedo & Juste, 2016) supports our finding among Portuguese Judo athletes.

Adaptability. Dieting and cutting extra weight to meet subcultural expectations of competitive Judo was a given example of adaptability. The concept itself was conveyed as a quality that promoted an athletic progressive evolution of a judoka within the cultural subdomain specific to Judo. Indeed, it was implicitly acknowledged as being a mid-term process of acculturation. Thus adding up evidence to the influence of sport-specific subcultural demands for building mental toughness in the elite, such as it was presented by Tibbert, Andersen, and Morris (2015). To our knowledge, an evident conceptual parallel does not seem to have been reported in any other mental toughness single-sport study. Moreover, considering that adaptability in the aforementioned sense cannot be mistaken for the ability to adapt, when faced with tough circumstances, that according to Galli and Vealey (2008) typifies resilience.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

The need for mental toughness may be less evident, if everything within an athlete's life is going very well and smoothly. However, a competitor is bound to face challenges, pressures and adversities. In this predominantly rough context, our results suggested that the mentally toughest judokas were acknowledged for performing accordingly to their level of preparation. This conceptual notion conveyed by the judokas interviewed is reinforced by the fact that sportsmen in general, but men particularly put pressure on themselves with concerns about performing poorly and making mistakes (Gyomber et al., 2015). Accordingly, among the mentally stronger Judo athletes underperforming was not expected, as consistent performances between non-testing training scenarios and evaluative sport competitions were considered key in our contribution to the concept of mental toughness. This consistence notion was simply a matter of competing within the limits of one's current fighting competence, regardless of both the opponents' performance and final outcome. One could lose a match to a more competent opponent and still exhibit mental toughness. Thus, tackling recent criticisms (e.g., Andersen, 2011), our contribution to the conceptual comprehension of mental toughness, emerging surprisingly from the raw data, distanced itself from the notion of being better than the opponents.

Our findings suggested that general elements of mental toughness across sports are likely to exist (e.g., emotional regulation, resilience, high motivation, self-confidence and concentration). Accordingly, to express an “aggressive” fighting style, intended to dominate the opponent physically and tactically (i.e., combativity) was suggested to be a mental toughness attribute distinctive in Judo. Along these lines, we found that the specific features of a sport can generate demand for psychological qualities not recognizable in many other sports as well as dismiss the need for generally recognized qualities. For instance, comparing our findings with the work of Jaeschke et al. (2016) it was clear the absence in Ultramarathon of explicit references to self-confidence and attention regulation as determinant mental toughness attributes. On the other hand, “team role responsibility” was one psychological quality not at all reported by the interviewed judokas in this study, but was understood to be a mental toughness characteristic in Australian Football (Gucciardi et al., 2008). This particular contrast between Judo as a predominantly individual sport and Australian Football as a team sport lends evidence on the hypothesis that some peculiar characteristics of mental toughness may exist across sports. Still, this does not support the existence of unique or exclusive characteristics of a sport, contrary to the understanding of Gucciardi et al. (2008). Nevertheless, our conclusions were consistent with those of Cook et al. (2014), insofar as similarities were predominant when comparing mental toughness attributes across sports so far studied.

Our results were based upon understandings of athletes ranging from lower to upper levels of competition, considering the nature of this combat sport. From a practical viewpoint, the knowledge resulting from this study will direct Judo coaches in their training practices towards the development of mental toughness characteristics particular to the sport. For instance, taking into account that for a consistent performance it will be important to minimize errors during combat in Judo, coaches should address athletes' attentional regulation capability according to sport-specific tactical-technical aspects. Even more, considering the work of Weinberg, Freysinger, Mellano, & Brookhouse (2016), sport psychologists will also benefit from this sport-specific knowledge, particularly by enabling them to tailor their interventions in accordance with the slightly divergent attributes of judokas' mental toughness hereby discussed (e.g., pragmatism, self-esteem). And, at the same time, allowing practitioners to address the development of mental toughness attributes in general recognized as such, regardless of the sport (e.g., emotional regulation, resilience, self-confidence).

This study may be useful to researchers' further efforts to conceptualize, measure and develop judokas' mental toughness. Nonetheless, further single-sport research based on different subcultural realities, other than the Portuguese community, would bring a greater insight about mental toughness in Judo. Since “mental toughness lends itself to being an umbrella term under which athletes conform to the sport's subcultural ideals” (Tibbert et al., 2015).