Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO  Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Nutrición Hospitalaria

versión On-line ISSN 1699-5198versión impresa ISSN 0212-1611

Nutr. Hosp. vol.18 no.3 Madrid may./jun. 2003

Nutritional assessment of adult patients admitted to a hospital of the Amazon region

K. Acuña*, M. Portela**, A. Costa-Matos***, L. Bora****, M. Rosa Teles*****, D. L. Waitzberg****** y T. Cruz*******

* Physician of FUNDHACRE. Clinical Nutrition Specialist (Brazilian Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (SBNPE).** Assistant Professor. Department of the Science of Nutrition. Nutrition School. Bahia Federal University. *** Medical student. Bahia Federal University Medical School. Special Training Program (PET). **** and ***** Medical residents in Internal Medicine. FUNDHAGRE. ****** Associate Professor. Division of Surgery of the Digestive System. Department of Surgery. São Paulo University Medical School. ******* Chief. Division of Endocrinology. Professor Edgard Santos University Hospital (HUPES). Bahia Federal University Medical School, Brasil.

| Abstract Changes in nutritional status are important in clinical practice because they relate to an increase in morbidity and mortality. Studies about nutritional problems in hospitalized adults have been reported since the 1970s. The prevalence of malnutrition has varied from 10 to 70%, depending on the diagnostic criteria used. The hospital studied and the duration of admission. (Nutr Hosp 2003, 18:138-146) Keywords: Nutritional assessment. Nutritional evaluations.

| EVALUACIÓN NUTRICIONAL DE PACIENTES ADULTOS INGRESADOS EN UN HOSPITAL DE LA REGIÓN AMAZÓNICA Resumen Los cambios del estado nutricional son importantes en la práctica clínica porque se relacionan con un aumento de la morbilidad y de la mortalidad. Desde los años 1970 se han comunicado estudios sobre los problemas nutricionales de los adultos hospitalizados. La prevalencia de la malnutrición varía del 10 al 70% según los criterios diagnósticos empleados, el hospital en cuestión y la duración del ingreso. (Nutr Hosp 2003, 18:138-146) Palabras clave: Evaluación nutricional. Evaluaciones nutricionales. |

Correspondencia: Katia Acuña.

Caixa Postal 152, Correio Central.

Rio Branco. Acre 69908-970, Brasil.

Tel.: 55 (68) 224 71 69; Fax 55 (68) 223 70 55.

Correo electrónico: ms.katia@ac.gov.br

Recibido: 19-VII-2002.

Aceptado: 20-X-2002.

Introduction

Malnutrition predisposes to several severe complications, including a tendency to infection, difficulty of scar formation, respiratory failure1, cardiac failure, a decrease in hepatic protein synthesis, reduction of glomerular filtration and of gastric acid production2. Malnutrition also contributes to increasc morhidity in hespitalized patients (slow scar formation with fistulas3, elevation of the rate of hospital infection)4. These complications lead to a delay in the duration of hospital stay, arise in coasts and in mortality, especially in surgical patients5. From this association the concept of .complications associated with the nutritional status. emerged3, 5-7, usually known as nutritional risk5. Some authors3 use this basis to consider the recognition of these complications as golden standard to classify patients as low or high risk. By doing so, the nutritional assessment of hospitalized patients is converted from a diagnostic tool into a prognostic tool3. Therefore several prognostic indexes of varied complexity combining anthropometric measurements with laboratory tests apeared in the pertinent literature8.

Otherwise, overweight and obesity are also risk factors for a varied number of health injuries, the most frequent being: ischemic heart disease, arterial hypertension, cerebral vascular accident, type 2 diabetes mellitus, cholelithiasis, osteoarthritis (especially of knees), postmenopausal breast cancer, endometrial cancer, reflux esophagitis, hiatus hernia and psychological problems9, 10.

Studies on malnutrition prevalence in hospital environment started in the eight decade of the last century, departing from the classical work of Butterworth11 entitled .The skeleton in the hospital closet., which arouse the attention for the possibility of finding malnutrition in inpatients12. Since then, several studies were developed but, nevertheless, the prevalence of malnutrition has presented wide variation depending of different parameters used for classification, as the type of population studied and the duration of hospital stay13-15.

Thus, the prevalence of malnutrition in American hospitals varied from 15 to 70%14. So that classifying malnutrition continues to be a controversial theme in the literature13. For this reason several authors recommended the creation of standards16, 17. Jeejeebhoy e tal.18 state that when malnutrition is recognized based only in one parameter, around a quarter of the population would be considered abnormal and, because of that, they suggested using at least three criteria.

In Brazil, a sectional, multicentric study with random choice of 4000 patients, entitled Inquerito Brasileiro de Avaliação Nutricional (IBRANUTRI), Brazilian Inquiry of Nutritional Assessment was performed. Its aims were: 1) to determine the prevalence of malnutrition in hospitals for adults belonging to the Sistema Único de Saúde (SUS) - Single Health System; 2) to examine closely the preoccupation of the health staffs with the nutritional status of these patients; 3) to evaluate the use of nutritional therapy13. The technique of nutritional assessment used was the .Avaliação Nutricional Subjetiva. (Subjective Nutritional Assessment) or .Avaliação Subjetiva Global, (Global Subjective Assessment) GSA, proposed by Detsky et al.19 This study revealed that almost half (48.1%) of hospitalized patients was malnourished; severe malnutrition was found in 12.5% of them; hospital related malnutrition progressed in proportion to the duration of hospital stay; that only in 18.8% of the medical charts there was any report on nutritional status of the patient and only 7.3% patients received nutritional therapy (6.1% enteral nutrition; 1.2% parenteral nutrition)4.

Taking into consideration the IBRANUTRI4 results and the lack of studies on nutritional assessment of hospitalized patients in the Northern region of Brazil, it was decided to performed the present study with the aim of assessing the nutritional status of adult patients hospitalized for surgical treatment in a public hospital from the State of Acre, located in Western Amazon Region.

Cases and methods

The present sectional study was performed from April 7 to May 27, 2002, in the Fundação Estadual do Acre (FUNDHACRE) - Acre State Foundation - Hospital, in the town of Rio Branco. This is an 150 beds general tertiary public institution that averages 650 monthly admissions. A pilot study had been done, in February and March 2002, for evaluation of the methodology to be used and reevaluation of sample size calculation by Epi-info (Version 6.0).

The sample of the study included 155 adult patients (age 20 to 59 years)20, consecutively admitted for elective surgical treatment. The nutritional assessment was performed within less than 24 hours of ad- mission in order to avoid possible progression of malnutrition1, 4, 21. Thus, the patients were evaluated in the day af admission, on the eve of surgery, after signing the Informed Consent (Termo de Consentimento Livre e Esclarecido), approved by the Ethics Committee in Research, FUNDHACRE.

Exclusion criteria comprised patients younger than 30 years and older than 60 years9, and those with motor handicap, mental deficit or impaired alertness, as well those unable to standup for anthropometric measurements (weight and height). Were also excluded patients transferred from another hospital or from other FUNDHACRE service where they had been hospitalized for more than 24 hours and those readmitted during the study but who had been already evaluated, besides those who refused to participate of the study.

A standard questionnaire was initially applied. It contained demographic data (age, gender, racial group, socio-economic status indicators), surgical diagnosis, associated conditions (arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, etc.), continuous use of medications, alcoholism, smoking, illegal drugs use. Physical examination intended to detect specific nutritional deficits22. Socio-economic status was determined by the sum of scores obtained by the analysis of the following items: occupation, school level, housing conditions. Minimal score possible was 0 (zero); maximal, 15 (fifteen). Using the median (six) as a limit, two categories of socio-economic status were established: zero to six- low; seven to fifteen - high.

The Global Subjective Assessment (GSA) proposed by Detsky et al.19, modified by Garavel et al.23, as suggested by Waitzberg and Ferrini24 and Coppini et al.25 was utilized. This methodology was preferred because it offers points for each item and the ultimate category is obtained by the sum of the scores. The GSA classification distinguishes the following categories: a) malnourished < 17 points; b) moderately malnourished or in nutritional risk - from 17 to 22 points; and c) severely malnourished > 22 points24, 25.

In the evaluation of the nutritional status of patients several parameters were used once in the pertinent literature there is lack of an universally accepted golden standard for the diagnosis of malnutrition and it has been suggested that the best method is the an organized way of multifatorial approach15.

Anthropometric data were gathered by three previously trained physicians. A beam scale with mobile weights26 (Brand Filizola®), previously submitted to metrological verification valid for one year by INMETRO-ACRE was used for weighing. This procedure was done after calibration of the gamut of the scale to zero22, the patient wearing standard hospital clothes, without shoes and with the bladder empty27. Two measurements were obtained and their average was registered9, 22, 26-28. Height was measured using the stadiometer of the scale28, following the same details as for weighing, besides not using anything in the head9, 26, 28. The average of two measurements was used. Body mass index was obtained using the formula BMI = weight (kg)/height (m)2, as preconized by WHO. Its 1985 ranges for underweight9 and the 1998 for obesity10 were used. These included the following categories: grade III underweight (severe): BMI < 16.0; grade II underweight (moderate): BMI 16.0 to 16.99; grade I underweight (mild): BMI 17.00 to 18.49; normal range: BMI 18.5 to 24.99; pre-obesity (overweight): BMI 25.0 to 29.99; grade I (moderate) obesity BMI 30.0 to 34.99; grade II (severe) obesity: BMI 35 to 39.99; and grade III (very severe, morbid) obesity BMI = 40.00 kg/m2.

Other anthropometric data were: (1) arm circumference (AC), obtained with a non stretchable metric scale in centimeters9, 22, 29; (2) triceps skin fold (TSF) was measured using the skin fold caliper or the Lange adipometer (with a 0.1 mm approximation, calibrated before and after the daily data collection using a calibrator block30). Both AMC and TSF were measured in the right arm of the patient in standing position9, 29, 30, 21; the average of three lectures was considered the final measurement24; (3) arm muscle circumference (AMC) was calculated using the formula9: AMC (cm) = AC (cm) - [II X TSF (cm)].

A blood sample of approximately 8 ml was taken from each patient for hematocrit (HT), hemoglobin (HG) and total lymphocyte count (LYMPH) determined by automatized lecture with an ABX® - Micros 60 apparatus. Serum albumin and total cholesterol were also enzimatically measured using Dimension A/R, Dade Behring® equipment. All the determinations were performed in the FUNDHACRE Clinical Pathology Laboratory.

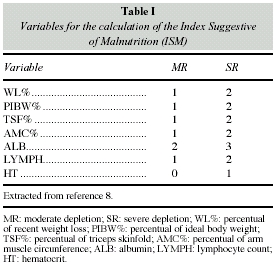

The index suggestive of malnutrition8, ISM, obtained by the sum of all pondered values attributed to seven nutritional parameters was used for classifying malnutrition.

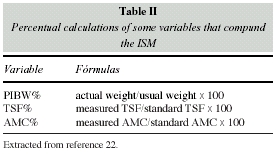

The patients whose results were ≥3 were considered malnourished (table I). The formulas for percentual calculations of the variables used for establishing an ISM8 are presented in table II, and their cutoffs in table III; the reference values of the anthropometric parameters are in table IV. The values for ISM calculation are described to facilitate their reproducibility, since they were obtained from different sources.

Ideal weight was calculated according to the age range and gender taking into consideration as the 50 percentile of the values based on the Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (HANES 1971-1974)22.

IMC was used for the classification of obesity, as it is considered to be a good indicator of excess deposit in the adult9, 10.

For data analysis the SPSS (version 9.0) program was used. The continuous variables were studied as averages, standard deviations, minimal and maximal values and were compared by the bicaudate Student t test for independent samples. The qualitative variables were evaluated by their percent values and compared using the quisquare test. The results of the statistical analysis were considered significant when the error probability was ≤ 0.05.

Results

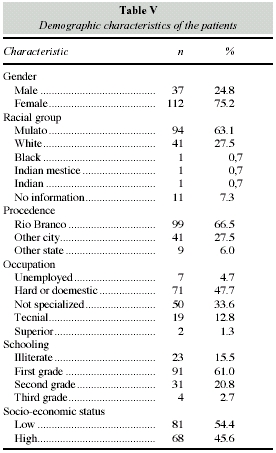

From the 155 patients evaluated sis (3.9%) were excluded due to loss of laboratory results. The demographic characteristics of the patients are presented in table V. From the 149 patients admitted for elective surgical treatment 112 (75.2%) were women, and 65 (58%) from them were hospitalized to undergo gynecological surgery (table VI). The average age of the male patients was 38 (± 12.7) years and that of women was 33.1 (± 8.75) years. The prevailing racial group was mulatto (94, or 63.1%). One hundred forty of the patients were born in the state of Acre and 99 (66.4%) in its capital, Rio Branco. As for occupation, 7 (4.7%) were unemployed and only two had a high standard occupation (table V). In terms of schooling (table V), most patients (76.5%) were either illiterate (23 or 15.4%) or had completed only the first grade (91 or 61.1%). Eighty-one patients (54.4%) were of a low socio-economic status and 68 (45.6%) had a high level of living.

Associated medical conditions, shown in Table VI, revealed that 16 (10.7%) patients had high blood pressure; among them, 9 (56.2%) presented with variable degree of excess of weight; two (1.3%) patients had the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus - they had a normal BMI. No other relevant coneorbitics were referred except for the (0.7%) case of a woman with a biliary pancreatitis that had occurred in the previous 6 months.

On physical examination, no specific nutritional deficiency was detected.

The Global Subjective Assessment (GSA) classified 100% of the patients of this study as well nourished; their points varied from zero to ten. The patient who had the highest score was the woman with a recent history of pancreatitis and she was classified as not having malnutrition; from the 28 patients with score 0 by GSA, 3 (10.7%) were considered malnourished according the Index Suggestive of Malnutrition (ISM).

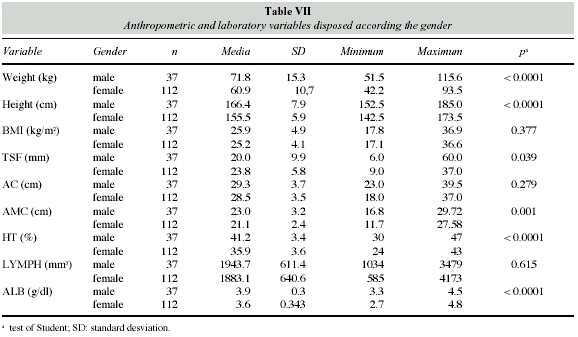

Table VII shows the findings of anthropometric and laboratory parameters, distributed by gender. The average weight for the male patients was 71.8 kg and for the women, 60.9 kg (p < 0.0001); the average height for the male patients was 152.5 cm, and for the female, 142.5 cm (p < 0.0001); the average BMI was 25.9 for men and 25.2 for woman (p = 0.377). The remaining informations may be seen in table VII.

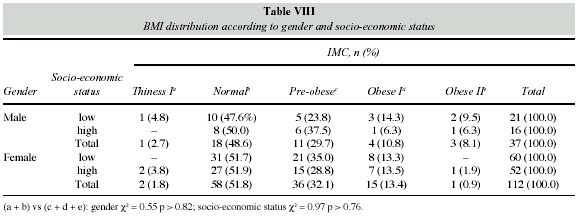

The BMI distribution according to gender and socio-economic status is shown in table VIII. Only 3 (2.0%) patients presented grade I underweight; 76 (51%) had a normal BMI; 47 (31.5%) were considered pre-obese; 19 (12.8%) were grade I obese (4 men, 10.8% of 37 and 15 women, 13.4% of the total number of 112); 4 (2.7%) were classified as having grade II obesity (3 men 8.1% of 37 and 1 woman, 0.9% of 112). No significant statistical differences between the BMI grades and socio-economic status (p > 0.76) and gender (p > 0.82) were found.

When calculations to define ISM were performed, 14 (9.4%) patients had to be excluded because they were unable to report their usual weight, preventing the determination of the weight loss percentage. In these cases the result was considered to be 0. ISM values obtained varied from 0 to 5; 18 (12.1%) patients were considered malnourished. Table IX shows the classification of malnutrition according to ISM in relation to gender and socio-economic status. From 37 men, 3 (8.1%) were considered malnourished; from the 112 women 15 (13.4%) had malnutrition, according to the ISM. When socio-economic status and gender were compared among well nourished and malnourished patients no statistically significant differences were found.

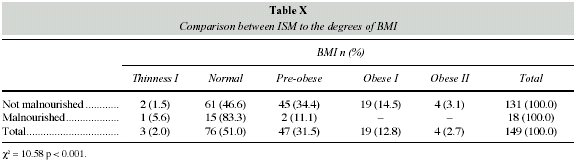

Table X compares ISM to the degrees of BMI. It is verified that 15 (19.7%) of the 76 patients classified as normally nourished using BMI could be identified as malnourished by the ISM; 2 of 47 (9.4%) pre-obese by BMI had malnutrition by ISM; and from 3 under weight patients in only 1 malnutrition was suspected.

Table XI shows BMI and ISM distribution for calculation of the kappa index (k). The concordance among them in the diagnosis of malnutrition was found to be, in the present series, equal to 0.07.

Discussion

The population evaluated in the present study included a majority of young women admitted to the hospital to undergo gynecological surgery, without relevant comorbidities and no apparent signs of specific nutritional deficit on careful physical examination.

These cases had and indication for elective surgery, had preoperative workup and pertinent laboratory tests and were considered fit for surgery. This leads to the deduction that they belong to the segment of the general population with no relevant heatin insult, the nutritional status included.

Perhaps for this reason GSA was unable to identify malnourished patients. Nevertheless GSA has been extensively studied and validated in the literature when it is compared with objective methods3, 4, 6, 7, 12, 24, 25, 32, 33. On the other side, the initial GSA model proposed by Detsky et al.9, which is considered highly subjective, may be applied by lowly experienced professionals since the concordance is referred to be 79%33.

The advantages of this method consist in being simple, of low coast, rapid use, and that it is adjustable ta several clinical situations5, 12. Besides, it may be considered as a prognostic criterion7. The findings of the present study may be explained taking into consideration the opinion of Jeefeebhoy et al.8, who consider that the GSA predictive value depends on the population evaluated, as GSA was able to anticipate complications in patients of a certain hospital and not in other. This observation indicates that GSA may be an index of disease better than of nutrition18. Other authors concluded that an elevated number of patients (> 100) is needed to obtain a reliable result25. Correia32 also observed that it seems to exist a tendency of GSA results to underestimate those encountered with anthropometric measures. In the present study, the hypothesis that GSA underrates the diagnosis of malnutrition32, is confirmed.

In the present study, men had higher height than women, and the statistical significance was compatible with literature reports. But they were shorter (minimal height, 122.5 cm) and lighter (minimal weight, 51.5 kg), when compared to North American standards of the Metropolitan Life Insurances Company (minimal height, 158 cm; lightest weight of small size, 58.3 kg)31. The same abservation was valid in relation to women (minimal height, 142.5 cm; weight, 42.2 kg) when compared to North American standards31 (minimal height, 148 cm; lightest weight of small size, 46,4 kg).

When considering the average age of men (38 ± 12.7 years) and the average weights (71.8 kg) and comparing to the North American standard for the age range, taking into consideration the 50th percentile (78.4 to 79.8 kg), it is observed that it remains smaller. The same fact was not observed in relation to women (average age 33.1 ± 8.75 years; average weights 60.9 kg) when compared to the American women 50th percentile of similar age (59.4 kg to 63.3 kg). When comparing with tables representing the Brazilian standard region by region24, constructed based on the Estudo Nacional de Defesa Familiar - ENDEF (National Study of Family Expediture, 1977, the average height of men was compatible (166.6 to 166.9 cm), the average weight was heavier (62.1 kg to 63.6 kg)24 for the same age range. In women the same fact was observed: the average height compatible and the average weight heavier when compared to the Brazilian interregional standard24 (154.9 cm to 155.8 cm; 52.4 kg to 55.2 kg). These findings may be explained when it is considered that two populational inquires were performed in Brazil, the first one in 1974-1975 (EN- DEF), and another in 1989 (Pesquisa Nacional sobre Saúde e Nutriçao - PNSN - National Survey of Health and Nutrition). It was demonstrated that the adult obese population almost doubled, dramatically affecting the malnutrition / obesity ratio, which suffered an inversion. Thus, in 1974, malnutrition exceeded obesity one and half fold, while in 1989 obesity supplanted malnutrition more 12 than two fold35. This phenomenon was called by Monteiro et al.35 the nutritional transition. It is being observed worldwide and was classified by WHO (World Health Organization)10 a global epidemic. Tables of weight and height for regions, reported from PNSN have not been available, since Coitinho et al.36 published tables using BMI only.

The triceps skin fold (TSF) offers an index of body fat and the arm muscle circumference is a measure of muscular mass6. The most common standards for comparison are the ones proposed by Jelliffe37, based on measurements in European military personnel and low intake American Wamen, and also the ones by Frisancho38, based on measures obtained in white American men and women who participated of the Health on Nutrition Survey (HANES), in 1971-1974. However, Thuluvath and Triger39 performed a study where they compared AMC and TSF in 125 patients with chronic liver disease using Jelliffe37 and Frisancho38 tables and demonstrated that both presented problems in reliability13.

This observation led them39 to ask .How valid are our reference standards of nutrition.11 If average values for TSF, AM and AMC are compared with those reported by Jelliffe37 but simplified by Waitzberg and Ferrin24 (table IV), it is found that AC values are simi- lar, but TSF are superior and AMC are inferior, suggesting that the population studied are presents a greater amount of fat than the reference standard.

In the present study, only 3 (2.0%) patients were grade I underweight; only one among them was considered malnourished by the ISM; of the 76 patients considered normal by BMI, 15 (19.7%) were found to be malnourished by ISM; two pre-obese patients were found to have malnutrition by ISM. The concordance between an index that uses several criteria for the diagnosis of malnutrition (ISM) and the BM was weak (k = 0.07). This suggested that in hospitalized patients in whom there is possibility to perform a more complex nutritional evaluation than in populational studies, BMI should be considered as an index of body proportional21 and not of nutritional status. However WHO preconizes using BMI for the diagnosis of malnutrition9, 10. This parameter has been utilized by several authors1, 16 with different cutoff points for classifying malnutrition in hospitalized patients.

Anjos40 states that there is no clear definition of the BMI limits to evaluate nutritional state. In spite of a committee of specialists gathered by WHO40 suggested the universal adoption of American Cutoff Points, other specialists committees40 have proposed using traditional limits (underweight: BMI < 20; normal: 20 to 25, overweight: 25 to 30, obese: > 30 kg/m2. Anjos40 also suggests that notwithstanding BMI does not indicate the body composition. The easiness of its mensuration and its relation with morbidity seem to be sufficient reasons for its use as an indicator of nutritional status in epidemiological studies, associated or not with anthropometric measurements.

ISM classified, in the present study, 18 (12.1%) patients as malnourished. Similarly as Kelly et al.16 discuss, our data can not be compared with the remaining data published in the pertinent literature that use different diagnostic criteria. Several prognostic indexes8 use high laboratory tests (ig. transferrin, delayed cutaneous hypersensitivity, total iron binding capacity, and alfa 1-glycoprotein, etc.), which are not routinely available in regions lacking resources for it, as the State of Acre, located in Western Amazonia. Thus, it was chosen to use ISM8 which, utilizing seven parameters and evaluating anthropometric measures and laboratory data, provides an appropriate way to characterize changes and in an accessible manner.

BMI classified 47 (31.5%) patients as pre-obese and 23 (15.4%) as grade I and II obese. Mc Whiter and Pennington1, considered BMI > 25 as overweight, found 34% and Velly et al.16 found 15% obesity using BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2. In relation to the population, PNSN36, considering BMI between 25 and 29.99 as overweight and ≥ 30 as obesity, found a 24.6% prevalence for overweight and 8.3% for obesity. In the present study a high prevalence of variable degrees of excessive weight was verified, especially among men for reasons so far unexplainable.

Conclusion

The evaluation of nutritional status, of great relevance in clinical practice, has not yet a golden standard to help making homogenous diagnosis; this has prevented comparisons between populations of hospitalized patients as well of outpatients. The diverse diagnostic criteria considerably contribute to the great variation of prevalence of malnutrition found, even if the different characteristics of hospital populations are taken into consideration. Another factor to be remembered in the construction of the diagnostic criteria are the different types of malnutrition. A critical point of the presently recommended diagnostics or prognostic indexes is coast, because many of these indexes require expensive laboratory tests sometimes not available for routine use in regions with shortage of resources.

In the present The Global Subjective Assessment (GSA) underestimated the diagnosis of malnutrition, showing more specificity than sensitivite. It represents, then, more an indicator of disease than of nutrition.

This study demonstrates that the body mass index (BMI) is not a good parameter to assess the nutritional status of adult patients, being preferentially a good indicator of status body proportions. To be clearer, a thin person may be well nourished and an obese individual may be malnourished.

Due to all these elements, the ISM proposed by Waitzberg8 seems to correspond to most, if not all, of the referred needs, since it combines several anthropometric and laboratory data of easy obtention and closely related to the nutritional status. Perhaps the weak point of this index comes out when it is compared with North American Standards, which have problems of reliability.

Another relevant factor observed in the present study is the prevalence of excessive weight (31.5% of pre-obesity and 15.4% of obesity). This demonstrates and calls attention for the fact that the nutritional transition observed in the Brazilian population already extends to adults seen when they are admitted to a hospital in the Western Amazonia.

References

1. McWhirter JP y Pennington CR: Incidence and regognition of malnutrition in hospital. BMJ, 1994, 308:945-948. [ Links ]

2. OMS, Organização Mundial da Saúde: Manejo da Desnutrição Grave: um Manual para Profissionais de Saúde de Nivel Superior e suas Equipes Auxiliares, Genebra, 2000. [ Links ]

3. Detsky AS, Baker JP, Mendelson RA, Wolman SL, Wesson DE y Jeejeebhoy N: Evaluating the accuracy of nutritional assessment techiniques applied to hospitalized patients: methodology and comparisons. J Parent Ent Nutr, 1984, 8:153-159. [ Links ]

4. Waitzberg DL, Caiaffa WT y Correia MITD: Inquérito Brasileiro de Avaliação Nutricional Hospitalar (IBRANUTRI). Rev Bras Nutr Clin, 1999, 114:123-133. [ Links ]

5. Silva MCGB: Avaliação Subjetiva Global. In: Waitzberg DL: Nutrição Oral, Enteral e Parenteral na Prática Clínica, 3. ed. Atheneu, São Paulo, 2000: 241-253. [ Links ]

6. Jeejeebhoy KN: Nutritional Assessment. Gastroenterology Clinics of North America, 1998, 27 (2):347-369. [ Links ]

7. Detsky AG: Nutritional status assessment: does it improve diagnostic or prognostic information? Nutrition, 1991, 7 (1):37-38. [ Links ]

8. Bottoni A, Oliveira GPC, Ferrini MT y Waitzberg DL: Avaliação Nutricional: Exames laboratoriais. In: Waitzberg DL: Nutrição Oral, Enteral e Parenteral na Prática Clínica. 3. ed. Atheneu, São Paulo, 2000: 279-294. [ Links ]

9. World Health Organization. Physical Status: the Use and Interpretation of Antropometry. Report of a WHO Expert Committee. Geneva, 1995. [ Links ]

10. WHO, World Health Organization. Obesity: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic. Geneva, 1998. [ Links ]

11. Butterworth CE Jr.: The skeleton in the hospital closet. Nutr Today, 1974, 9:4-8. [ Links ]

12. FELANPE: Federação Latinoamericana de Nutrição Parenteral e Enteral. Terapia Nutricional Total: livro de trabalho do instrutor. Desnutrição e suas conseqüências, 1997, S1.1- S1.10. [ Links ]

13. Correia MITD, Caiaffa WT y Waitzberg DL: Inquérito Brasileiro de Avaliação Nutricional Hospitalar (IBRANUTRI): Metodologia do estudo multicentrico. Rev Bras Nutr Clin, 1998, 13:30-40. [ Links ]

14. Albert MB y Callaway CW: Clinical Nutrition for the House Officer. Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, 1992. [ Links ]

15. Smith LC y Mullen JL: Nutritional assessment and indications for nutritional support. Surgical Clinics of North America, 1991; 71:449-457. [ Links ]

16. Kelly IE, Tessier S, Cahill A y cols.: Still hungy in hospital: identifying malnutrition in acute hospital admissions. QJM, 2000, 93 (2):93-98. [ Links ]

17. Bistrian B: Anthropometric norms used in assessment of hospitalized patients. Am J Clin Nutr, 1980, 33:2211-2214. [ Links ]

18. Jeejeebhoy KN, Detsky AS y Baker JP: Assessment of Nutritional Status. J Parent Ent Nutr, 1990, 14 (5):193S-196S. [ Links ]

19. Detsky AL, Mclaughilin JR, Baker Jr y cols.: What is subjective global assessment of nutritional status? J Parent Ent Nutr, 1987, 11:8-13. [ Links ]

20. Acuna K: Avaliação do Estado Nutricional de Adultos Internados em Hospital Público do Acre. Dissertação de Mestrado. Universidade Federal da Bahia, 2002. [ Links ]

21. Weinsier RL, Hunker RN, Krumdieck CL y Butterworth CE Jr.: A prospective evaluation of general medical patients during the course of hospitalization. Am J Clin Nutr, 1979, 32:418-426. [ Links ]

22. Waitzberg DL y Ferrini MT: Exame Físico e Antropometria. In: Waitzberg DL: Nutrição Oral, Enteral e Parenteral na Prática Clínica. 3. ed. Atheneu, São Paulo, 2000: 255-278. [ Links ]

23. Garavel M, Hagaman A, Morelli D, Rosenstock BD y Zagaja J: Determinating nutritional risk: assessment, implementation, and evaluation. Nutrition Support Services, 1988, 18: 19. [ Links ]

24. Waitzberg DL y Ferrini MT: Avaliação Nutricional. In: Waitzberg DL: Nutrição Enteral e Parenteral na Prática Clínica. 2. ed. Atheneu, São Paulo, 1995: 127-152. [ Links ]

25. Coppini LZ, Waitzberg DL, Ferrini MT, Teixeira da Silva ML, Gama-Rodrigues J y Ciosak SL: Comparação da avaliação nutricional subjetiva global x avaliação nutricional objetiva. Rev Ass Med Brasil, 1995, 41 (1):6-10. [ Links ]

26. Heyward VH y Stolarczysk LM: Avaliação da Composição Corporal Aplicada. 1. ed. Manole, Método Antropométrico. Sao Paulo, 2000: 73-98. [ Links ]

27. Heymsfield SB, Tighe A y Wang Z: Nutritional assessment by anthropometric and biochemical methods. In. Shils ME, Olson JA, Moshe S: Modern Nutrition in Health and Disease. 8. ed. Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, 1994: 812-841. [ Links ]

28. Gordon CC, Chumlea WC y Roche AF: Stature, Recumbent Length, and Weight. In: Lohman GT, Roche AF, Martorell R: Anthropometric Stardardization Reference Manual. Abridged ed. Champaign: Human Kinetics Books, 1988: 3-8. [ Links ]

29. Harrison GG, Buskirk ER, Carter JEL y cols.: Skinfold thicknesses and measurement technique. In: Lohman GT, Roche AF, Martorell R: Anthropometric Stardardization Reference Manual. Abridged ed. Champaign: Human Kinetics Books, 1988: 55-70. [ Links ]

30. Heyward VH y Stolarczysk LM: Avaliação da Composição Corporal Aplicada. 1. ed. Manole, Método das Dobras Cutâneas, São Paulo, 2000: 23-46. [ Links ]

31. Gibson RS: Nutritional Assessment. A Laboratory Manual. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993. [ Links ]

32. Correia MITD: Avaliação Nutricional Subjetiva. Rev Bras Nutr Clin, 1998, 13:68-73. [ Links ]

33. Pereira MG: Epidemiologia: Teoria e Pratica. Guanabara Koogans, Rio de Janeiro, 1995. [ Links ]

34. Hirsch S, Obaldia N, Petermann M y cols.: Subjective global assessment of nutritional status: further validation. Nutrition, 1991, 57 (1):35-37. [ Links ]

35. Waitzberg DL: Avaliação nutricional de pacientes no pré e pós-operatório de cirurgia de aparelho digestivo. Método antropométrico e laboratorial. Tese de Mestrado. Universidade de São Paulo, 1981. [ Links ]

36. Monteiro CA, Mondini L, Medeiros de Souza AL y Popkin BM: Da desnutrição para a obesidade: a transição nutricional no Brasil. In: Monteiro CA: Velhos e Novos Males no Brasil. A Evolução do Pais e de suas Doenças. HUCITEC/USP, São Paulo, 1995. [ Links ]

37. Coitinho DC, Leão MN, Recine E y Sichieri R: Condições Nutricionais da População Brasileira: Adultos e Idosos. INAM, Brasilia, 1991. [ Links ]

38. Jelliffe DB: The assessment of nutritional status of the community. World Health Organization, Geneve, 1966. [ Links ]

39. Frisancho AR: New norms of upper limb fat and muscle areas for assessment of nutritional status. Am J Clin Nutr, 1981, 34:2540-2545. [ Links ]

40. Thuluvath PJ y Triger DR: How valid are our references standards of nutrition? Nutrition, 1995, 11 (6):731-733. [ Links ]

41. Anjos LA: Índice de massa corporal (massa corporal · estatura2) como indicador do estado nutricional de adultos: revisão da literatura. Rev Saúde Públ, 1992, 26 (6): 41-46. [ Links ]