INTRODUCTION

A series of nationally representative health and nutrition surveys (1988, 1999, 2006, 2012) have shown a "polarized model of nutrition transition" in Mexico 1 characterized by a rapid increase in nutrition-related non-communicable diseases, a reduction of infectious diseases 2, excessive energy intake and reductions in physical activity 3. However, recent studies have shown that micronutrient deficiencies and iron deficiency anemia are still significant public health problems, affecting the most vulnerable age and gender groups 4. The consequences of nutrition deficiencies during childhood lead to growth retardation, decreased learning capacity and impaired immune response. Additionally, under-nourishment is causally related to a higher risk of chronic disease in adulthood 5. The coexistence of excess and deficiency conditions complicates the epidemiologic overview in Mexico.

Nowadays, public health decision-makers have to deal with both sides of malnutrition and this is the greatest challenge the public health system in Mexico has to overcome.

The objective of this paper is to estimate and compare energy and nutrient intake and dietary adequacy according to biological, social and nutritional characteristics in a nationally representative sample of Mexican children aged one to four years of age.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

POPULATION AND SAMPLE SIZE

Data for this analysis were obtained from the Mexican National Health and Nutrition Survey 2012 (ENSANUT-2012 by its Spanish acronym). The ENSANUT-2012 was developed from October 2011 to May 2012. This included a probabilistic sample of 50,000 households representative at national, regional and state levels. The sampling framework for selecting the households was provided by the National Institute of Statistics, Geography and Informatics. The study population for the present analysis included preschool aged children, age range 1-4 years.

DIETARY INFORMATION

A random subsample of approximately one-sixth of the 50,000 total households participating in ENSANUT-2012 was selected 6. Dietary information was obtained for 1,338 children from one to four years of age. Standardized personnel administered a semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire (SFFQ) to women or caregivers. The questionnaire included 140 food items classified in 14 groups (dairy products; fruits; vegetables; fast food; meat, sausages and cold cuts; fish and seafood; legumes; cereals and tubers; corn products; beverages; snacks, candies and desserts; soups and creams; condiments; corn tortillas). The interviewers asked for the days of the week, times of the day, portion sizes and total portions consumed for each food item during a seven-day period before the interview.

ETHICS

Informed consent was obtained from parents or guardians in order to participate in the study. The protocol was previously approved by the Research Ethics Committee and Committee on Biosafety and Research at the National Institute of Public Health, Mexico.

OUTCOME VARIABLES DEFINITIONS

Intake

The estimated quantity of energy, fiber, and macro and micronutrients was calculated using food composition tables compiled by the INSP. The methodology and procedures have been described by Ramírez-Silva I et al. 7.

Energy intake, carbohydrates, proteins, lipids, fiber, vitamins A, C, B12, and D, folates, total iron, heme iron and non-heme iron, zinc, calcium and types of fats were reported.

Intake adequacy percentages

The percentage of energy adequacy was estimated based on the Estimated Energy Requirement. For carbohydrates and fat, 55% and 30%, respectively, of the energy derived from those macronutrients was used as adequacy values 7,8.

The adequacy of protein, zinc, vitamin C, vitamin B12, vitamin D, retinol equivalents and folates was calculated according to age as a percent of the Estimated Average Requirement 8,9,10,11-12.

For calcium and fiber, the adequate intake value was used since the estimated average requirement value has not been calculated due to lack of information 7,13.

OTHER VARIABLES FOR ENSANUT-2012 ANALYSES

Country regions

The country was divided into three regions: North (Baja California, Baja California Sur, Coahuila, Chihuahua, Durango, Nuevo León, Sonora, Tamaulipas); Mexico City/Central (Aguascalientes, Colima, Estado de México, Guanajuato, Jalisco, Michoacán, Morelos, Nayarit, Querétaro, San Luis Potosí, Sinaloa, Zacatecas, Mexico City); and South (Campeche, Chiapas, Guerrero, Hidalgo, Oaxaca, Puebla, Quintana Roo, Tabasco, Tlaxcala, Veracruz, Yucatán).

Area of residency

The area of residency was classified according to the number of inhabitants, considering those with 2,500 or more people as urban, and those with < 2,500 as rural.

Nutritional status

Data on length/height and weight were transformed to Z-scores using the World Health Organization (WHO) reference pattern 14.

Indigenous ethnicity

A child was classified as indigenous when the head of the household self-reported as a speaker of an indigenous language.

Social programs

This variable considers the food programs included in the survey in which the beneficiary was the child or from which the child indirectly benefitted.

Socioeconomic status

It was constructed using principal components analysis with variables of housing and availability of goods and services. The first component explained 40.5% of the variance with a value (lambda) of 3.24 was selected as the index. The index was further divided into low, middle and high.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

One hundred and twenty-six observations were excluded, accounting for 9.4% of the original sample, for not having plausible information.

The median intake and adequacy was estimated using quantile regression models because the quantile regression aims at estimating the conditional median of the response variable. After the bivariate analysis, the selected variables to be adjusted were age (continuous), socioeconomic status, region and area of residence. We also estimated inter-quartile range from marginal effects after quantile regression for comparison across the categories of interest. For categorical variables, differences in percentages were analyzed by Z test, and p values < 0.05 were considered as significant.

All estimations were weighted by expansion factors, and adjusted for design sampling (cluster and strata) effects using the STATA software SVY module for complex surveys (STATA version 13.0, 2013. College Station, TX: Stata Corp LP). A statistically significant level of 0.05 was used.

RESULTS

The study population consisted of 1,212 children aged one to four. Fifty-one percent were boys and the mean age was 3 ± 1.1 years. Just over 25% of preschoolers had some type of malnutrition. Close to 10% of the children were of indigenous ethnicity and more than 50% were beneficiaries of social programs. About half of the population lived in the Mexico City/Central region and more than two thirds lived in urban areas (Table 1).

Table I. Characteristics of 1 to 4-year-old children. National Health and Nutrition Survey 2012. Mexico

Analysis by complex design survey. All children, n = 1,212. Nutritional status, n = 1,132. Social programs, n = 977.

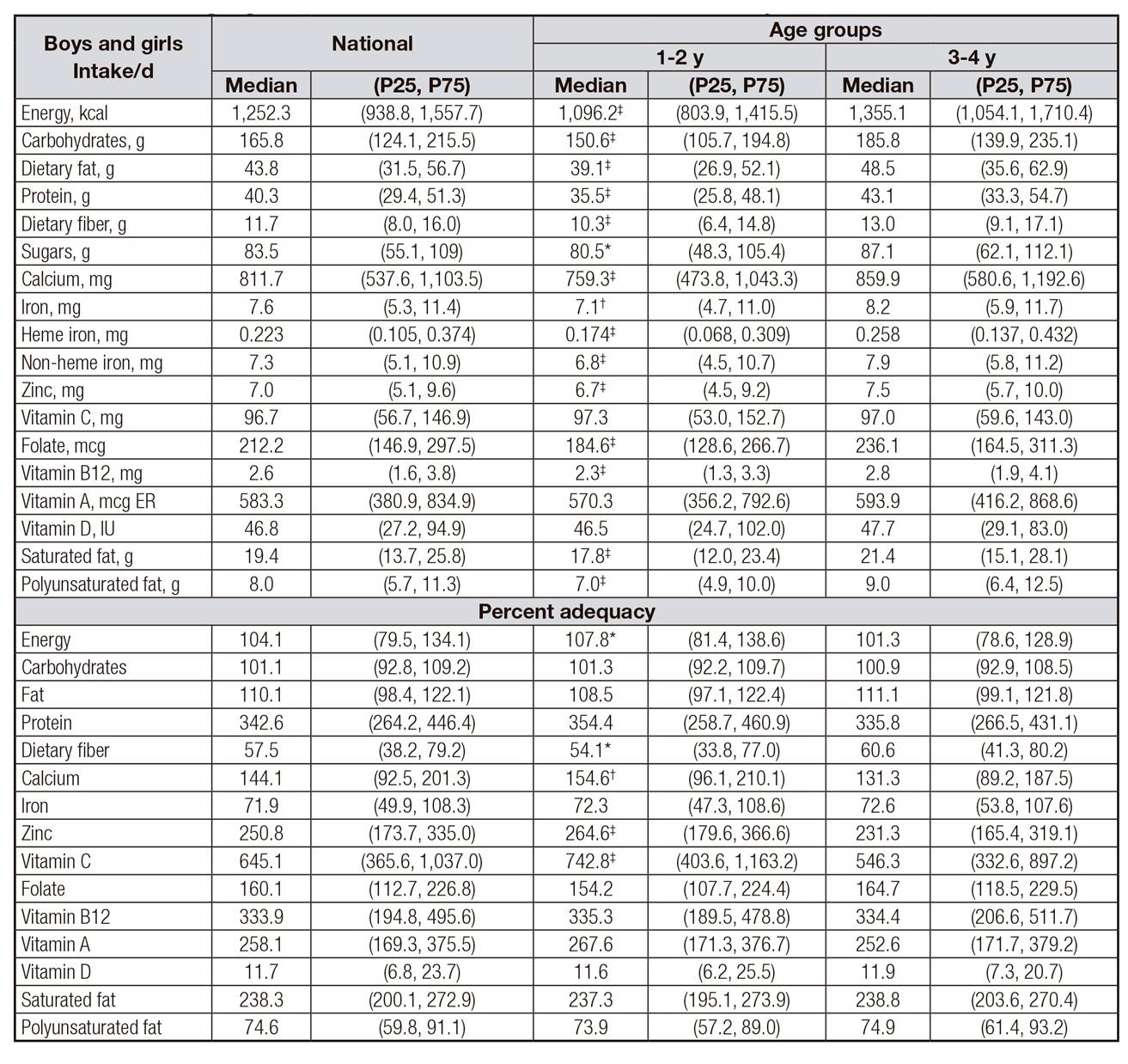

INTAKES AND ADEQUACY PERCENTAGES

Nationally, the percent adequacy for energy and carbohydrate intake was close to 100% and it was above 100% for fat (110.1%), calcium (144.1%) and folate (160.1%). Adequacies well above 100% were observed for protein (342.6%), zinc (250.8%), vitamin C (645.1%), vitamin B12 (333.9%), vitamin A (258.1%) and saturated fat (238.3). Low percent adequacies were observed for fiber (57.5%), iron (71.9%), polyunsaturated fat (74.6%) and vitamin D (11.7%). Adequacies for energy, calcium, zinc and vitamin C were higher in children aged one to two years compared with children three to four years of age, except for fiber, which was higher among the older children (Table 2).

Table II. Intake and percent adequacy of intake in 1 to 4-year-old children, national and by age groups. National Health and Nutrition Survey 2012. Mexico

Analysis by complex design survey, adjusted by U/R location and region and socioeconomic level. 95% confidence intervals. Statistically significant differences:

*p < 0.1;

†p < 0.05;

‡p < 0.01.

For carbohydrates, fat and saturated fat considered at-risk when intake was above 100% of their requirement.

Intakes were lower in the South region compared to the other regions except for fiber, which presented the lowest intake in the North compared to the South region. Also, the lowest adequacies for energy, iron and vitamin D were observed in the South region. Most intakes were higher in urban compared to rural areas, as proteins, folate and saturated fat (Table 3).

Table III. Intake and percent adequacy of intake in 1 to 4-year-old children, national and by region and area. National Health and Nutrition Survey 2012. Mexico

Analisys by complex design survey adjusted by U/R location, region and socioeconomic level. 95% confidence intervals. Different letters mean statistically significant differences between comparison groups:

*p < 0.1;

†p < 0.05;

‡p < 0.01.

For most macro and micronutrients, indigenous children had lower intakes and percent adequacies, compared to non-indigenous children, except for fiber which was slightly higher among indigenous children (Table 4).

Table IV. Intake and percent adequacy of intake in children 1-4 years of age by ethnicity. National Health and Nutrition Survey 2012. Mexico

Analysis by complex design survey, adjusted by age, U/R location, region and socioeconomic level.

95% confidence intervals. Statistically significant differences:

*p < 0.1;

†p < 0.05;

‡p < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

At a national level, preschool-aged Mexican children have protein, saturated fat, calcium, zinc, vitamins A, C, B-12 and folate intakes exceeding the current recommendations for age. In depth analyses suggest that high intake of these nutrients is explained not only by the consumption of foods in their natural form, but also by the consumption of fortified foods provided by National Nutrition Programs, like Prospera 15, Liconsa 16 and foods fortified by the food industry which are highly available in the market (data not shown). Mexican children consumption of dairy products (i.e. milk, and cheese) contributed significantly to protein, calcium, vitamin B12 and saturated fat intake, as well as zinc and vitamin A to a lesser degree and significantly higher energy intake compared with not-dairy intake consumers 17.

Preschool-aged children showed a high intake of folate mainly from a high consumption of fruits and vegetables, dairy products and ready-to-eat breakfast cereal, pastas, pies, cookies and sweets, all of them fortified by the food industry 18.

Another finding is the high intake of vitamin C among preschool Mexican children, which was eight times greater than the requirements. This high intake can be explained by the consumption of fruits and vegetables, such as guava and mango, all rich in vitamin C.

It is important to note that highly processed foods are not only the main contributors of vitamin C and folate, but also of total energy, saturated fat, sodium and sugar among children 19,20.

We observed that, at a national level, Mexican preschool children have a low intake of dietary fiber, iron, vitamin D and polyunsaturated fats. A study of trends in dietary intake in Mexico in the 1980-2008 21 period showed that there has been a significant increase in national consumption of poultry and eggs, oil and soda, while there has been a decrease in the consumption of those considered as basic foods in the Mexican diet such as tortillas and beans, an important source of fiber.

It is important to note that the diet in the Mexican population tends to be rich in legumes, which mainly contain non-heme iron and phytates, resulting in a lower bioavailability of dietary iron. In our study we used the Mexican reference to determine iron requirement, which already considered the lower bioavailability, thus overestimation of iron absorption has been avoided 9.

This study shows an extremely low intake of vitamin D. These results are consistent with ENSANUT-2006. An analysis in Mexican children 2-5 years of age showed that the prevalence of marginal deficiency (< 50 nmol/l of 25-hydroxy-vitamin D) was 25% and insufficient vitamin D levels (< 75 nmol/l 25-hydroxy vitamin D) were observed in 55% of the children 22. This problem of low intake and vitamin D deficiency has been recently documented in Latin America 23.

In our population, the main dietary source of vitamin D is milk, which contributes more than 90% of intake for this vitamin. Currently, in Mexico, fortification/addition of milk with vitamin D is mandatory to 200 IU/l 24. However, based on the level of fortification, an individual would have to consume two liters of milk per day in order to meet the recommended vitamin D intake for preschool children (400 IU/d) 13.

Our results show that a lower intake of important nutrients such as iron and polyunsaturated fats persists among preschool children of economically disadvantaged populations, such as children living in the southern region of the country (the poorest region in Mexico) and rural areas and indigenous children 25. This is mainly due to the quality and diversity of the diet, which are determined by the income, given that, in situations of food insecurity or economic crisis, families in poverty change their diet and certain foods consumption as whole grains, animal products, fruits and vegetables are negatively affected 26.

So, preschool-aged Mexican children have a saturated fat intake above what is recommended, along with a low intake of polyunsaturated fat compared to the current recommendations, similar results to high income countries 27,28. This is consistent with the fact that obesity and many nutrition-related chronic illnesses are not just determined by some risk factors in mid-adult life, but begin during fetal development and early infancy and childhood 29.

Similar results of excess intake of folate, vitamin A, zinc, as well as low intake of iron and fiber, have been reported in American preschoolers 30.

Dietary risk, particularly in relation to iron deficiency, was also observed. Studies describing the frequency and severity of anemia and associated nutritional variables indicated that iron deficiency is the main cause of anemia in Mexican children < 5 years 31.

This study presents some limitations. First, it is well known that the SFFQ is subject to various errors in its application and reporting. However, our personnel were trained and standardized to apply it equally to all subjects 7, while the use of food frequency method has shown to be one of the best methods to estimate diet in young children 32 and the caretaker is a valid and useful strategy to obtain the information with respect to the child's consumption 33.

Second, the intake of water-soluble vitamins like vitamin C and B complex may be overestimated because in the food composition tables used for these analyses, losses by cooking or industrial processes were not considered, nor were losses to vitamin degradation which occurs between the date of preparation of fortified food and the date of expiration 34.

The study has important strengths because these data derived from a national Mexican population survey that was representative of areas, regions and states of the country. The SFFQ instrument captures food habits from seven days before the interview, which diminished memory bias.

At a national level, the next steps could be aligned to international recommendations such as the 4th goal of 2015 Millennium Development Goals 35 for young children to improve complementary feeding, in addition to breastmilk, as an important way to prevent under-nutrition and to reduce child mortality.