INTRODUCTION

Mental health is a multidimensional state of well-being, with negative indicators such as body image dissatisfaction (1), depression, and positive indicators such as self-esteem (2). Mental illness and the negative consequences of poor mental health among children and the youth are particularly a public health priority.

In this sense, regular physical activity (PA) has been found to have a positive association with mental health (3). Likewise, evidence suggests that participation in PA programmes may support young people’s current and future mental health (4). Some studies have reported negative associations between bad PA patterns and poor psychosocial well-being (5), as excessive screen time is strongly associated with depressive disease (6). However, these associations have not been extensively studied (7) and thus need to be investigated more thoroughly.

In the same way, school-age obesity is associated with psychosocial alterations, including deficiencies in social coexistence, with consequences for quality of life (8). It has been observed that obese children tend to have affective problems, which may negatively affect their academic performance (9). Therefore, the relationship between mental illness (i.e., with psychosocial origin) and well-being is an important area of public concern (10).

Various studies have reported that self-esteem is associated with children’s social, emotional, behavioural, and mental health (11). Self-esteem plays an important role during childhood and adolescence (12), with low self-esteem being recognized as being strongly associated with different risk factors for mental health issues that affect childhood development (11). In contrast, high self-esteem has been associated with better cognitive development (13) and quality of life (14).

Body image dissatisfaction in children and adolescents has negative implications for psychological and physical well-being (1). Previous studies have stressed the importance of exploring factors that influence body image dissatisfaction in order to avoid future psychosocial problems, along with other health-related consequences, for children (15). Additionally, depression is a serious psychiatric illness in children (16), often persisting into adolescence and young adulthood, and with severe negative consequences—including self-harm and suicide (17).

A growing proportion of children’s leisure time is spent as ‘screen time,’ including the use of smartphones, tablets, gaming consoles, and televisions—a pattern that has raised concerns about its effect on their psychological well-being (18). Lower levels of PA and higher levels of screen time and obesity are associated with impaired psychological well-being in children (19,20). However, research exploring screen time, after-school PA, weight status and psychological effects (i.e., self-esteem, body image and depression) among children need to be studied deeply. Therefore, the hypothesis of the study was that good PA patterns and normal weight status are associated with psychological well-being, and the aim of this study was to compare psychological well-being in groups of schoolchildren according to PA patterns and weight status, and to determinate the association between psychological well-being and both screen time and after-school PA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

PARTICIPANTS

The sample for this cross-sectional study comprised girls (n = 272; aged 11.93 ± 0.94 years) and boys (n = 333; aged 12.09 ± 1.00 years) attending a public primary school in Chile, and selected using convenience criteria. Sample size is similar to that of previous studies (21,22). Inclusion criteria were as follows: a) informed parental consent and participant consent; b) attending school, and c) aged between 11 and 13 years. Exclusion criteria were: a) the presence of musculoskeletal disorders or any other medical condition that might affect health and PA levels, and b) physical, sensory or intellectual disabilities. The tests were explained to all participants before the study began, and they were asked to abstain from intense exercise for 48 hours prior to the study.

Parents and guardians were informed about the study and provided their written consent for their children’s participation. In addition, all children provided a written assent on the day of the assessment. The investigation complied with the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Ethical Committee at Universidad de La Frontera (DFP16-0013), Temuco, Chile.

MEASUREMENTS

Anthropometric assessment

Body mass (kg) was measured using an electrical TANITA™ scale (Scale Plus UM-028; Tokyo, Japan) while wearing underclothes, without shoes. Height (m) was measured with a SECA™ stadiometer (Model 214; Hamburg, Germany) graduated in millimetres. The nutritional status of the participants was assessed according to obesity categories, estimated from the body mass index (BMI) and calculated by dividing body weight by the square of their height in meters (kg/m2). Based on the growth table published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Overweight and Obesity (CDC) for children of the same age and sex, “overweight” was defined as a BMI at or above the 85th percentile but below the 95th percentile, and “obesity” was defined as a BMI at or above the 95th percentile (23,24).

Waist circumference (WC) was measured at the height of the umbilical scar using a SECA™ tape measure (Model 201; Hamburg, Germany) (25). The waist-to-height ratio (WtHR) was subsequently obtained by dividing the WC by height in order to estimate the accumulation of fat in the central zone of the body, consistent with international norms (26). The percentage (%) of body fat (BF) was estimated from measurements of the subcutaneous tricipital and subscapular folds using a Lange™ skinfold calliper (102-602L; Minneapolis, USA) and calculated using Slaughter’s formula (27): Girls: %BF = 1.33 (tricipital + subscapular) - 0.013 (tricipital + subscapular)2 - 2.5. Boys: %BF = 1.21 (tricipital + subscapular) - 0.008 (tricipital + subscapular)2 - 1.7. The research assistant was submitted to the test-retest (n = 62) protocol to verify the technical measurement error with an intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC), in WC (ICC = 0.94), tricipital fold (ICC = 0.91) and subscapular fold (ICC = 0.91).

Psychosocial outcomes

The Body Shape Questionnaire (BSQ) was used to identify body image dissatisfaction (28). This questionnaire is comprised of 34 items; answers are given using a 6-point Likert scale (1, never; 2, rarely; 3, sometimes; 4, often; 5, very often; and 6, always). The maximum score is 204 points and the minimum is 34 points. Higher scores indicate ‘higher dissatisfaction’ with one’s body image. Scores were categorized as follows: < 81, ‘no dissatisfaction’; 81-110, ‘mild dissatisfaction’; 111-140, ‘moderate dissatisfaction’; and > 140, ‘extreme dissatisfaction.’ The level of internal consistency reached in this questionnaire presented a Cronbach’s alpha = 0.84.

For the self-esteem measurement we used the Coppersmith Self-Esteem Inventory (29). This self-report questionnaire is designed to measure attitudes toward the self in a variety of areas (family, peers, school, and general social activities). The instrument is one of the most commonly used assessment of self-esteem in both research and clinical practice. The scores for self-esteem were categorized as follows: < 22 points, ‘very low’; 22-26, ‘low’; 26-35, ‘normal’; 35-39, ‘high’; > 39, ‘very high.’ The inventory has been validated in Chilean children (30). The level of internal consistency reached in this questionnaire presented a Cronbach’s alpha = 0.86.

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Child Depression Inventory (CDI) (31), which consists of 27 groups of three statements relating to depressive symptoms over the previous 2 weeks. A score ≥ 18 points indicates the probable presence of clinically significant depression. The CDI has been validated in Chilean children (32). The level of internal consistency reached in this questionnaire presented a Cronbach’s alpha = 0.85.

Screen time and after-school PA

The PA patterns were evaluated with the Krece Plus test (33). The Krece Plus test is a quick questionnaire that classifies lifestyle based on the daily average of hours spent watching television or playing video games (screen time) and the hours of PA after school per week. The classification is made according to the number of hours devoted to each activity. The total points are added, and the person is classified as good (men: ≥ 9, women ≥ 8), regular (men: 6-8; women: 5-7) or bad (men: ≤ 5 and women: ≤ 4) according to the lifestyle score.

Procedure

Previously-trained research technicians visited selected schools during the 2018 Chilean school year and gave oral and written information to parents/tutors about participation in the research. Anthropometric assessments were carried out in a private room of the school at a comfortable temperature. The questionnaires were administered in classrooms on different days from the anthropometric evaluations. Only one questionnaire was administered per day. All measurements were taken in the morning between 09:00 and 11:00 am.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with the SPSS version 23.0 software (SPSS™ IBM Corporation, NY, USA). The continuous variables all showed a parametric distribution and are reported as the mean and standard deviation. Group differences were assessed by one-way ANOVA, and the post-hoc analysis was carried out using Bonferroni’s method. The ptrend was calculated by linear-by-linear association to establish a trend between h/day of screen time and psychological well-being. To determine the association between psychological well-being with screen time and PA after school, a multivariate logistic regression was used. Values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Table I shows the descriptive characteristics of the schoolchildren. There were sex differences in percentage of BF (girls 25.33 ± 7.31%, boys 24.00 ± 7.51%; p = 0.029) and body image dissatisfaction (girls 59.88 ± 31.92, boys 53.49 ± 27.42; p = 0.008).

Table I. Descriptive characteristics of the schoolchildren

The data shown represent mean ± DS, and n (%). p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

BMI:body mass index;

WC:waist circumference;

WtHR:waist-to-height ratio;

BF:body fat;

PA:physical activity.

Table II shows the results according to PA patterns. There were significant differences between the ‘good PA’ and ‘bad PA’ pattern groups on the variables of self-esteem (34.82 ± 7.01 and 30.79 ± 8.57, respectively; p = 0.013) and depression (10.16 ± 5.09 and 12.91 ± 6.64, respectively; p = 0.035). The schoolchildren who reported screen times of 5 or more hrs/day reported higher depression levels (ptrend = 0.003) than their peers (4 or less hrs/day) (Table III). Moreover, the group of schoolchildren with bad PA patterns reported higher screen time (3.92 ± 0.82 h/day) and lower levels of after-school PA per day (1.79 ± 1.04 h/week) in comparison to the ‘regular’ and ‘good PA’ pattern groups (p < 0.001) (Table II).

Table II. Comparison of variables according to physical activity patterns (screen time and PA after school)

The data shown are represented as mean ± SD. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. A denotes good PA groups, B denotes regular PA groups, and C denotes bad PA groups in the post hoc analysis.

Table III. Psychological well-being according to screen time

The data shown are represented as mean ± SD. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

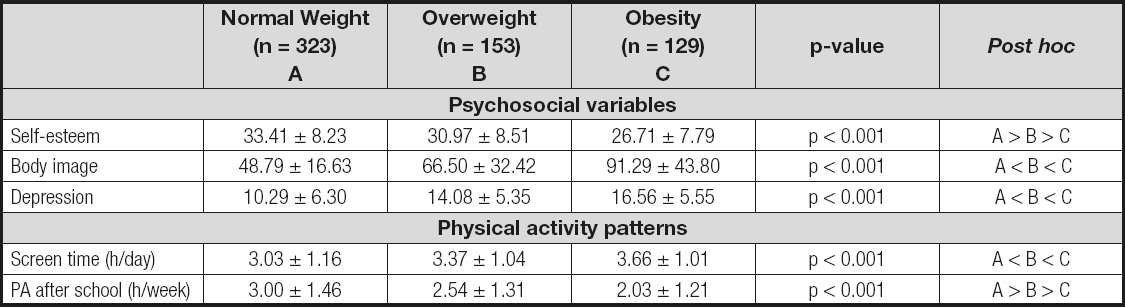

As shown in table IV, the normal-weight group was significantly different from the obese group in levels of self-esteem (33.41 ± 8.20 and 26.71 ± 7.79, respectively; p < 0.001), body image dissatisfaction (48.84 ± 16.76 and 91.29 ± 43.66, respectively; p < 0.001) and depression (10.29 ± 6.30 and 16.56 ± 5.56, respectively; p < 0.001). Likewise, there were significant differences between the normal-weight, overweight and obese groups in screen time (3.03 ± 1.16 vs. 3.37 ± 1.04 vs. 3.66 ± 1.01 h/day, p < 0.001) and PA after school (3.00 ± 1.46 vs. 2.54 ± 1.31 vs. 2.03 ± 1.21 h/week, p < 0.001).

Table IV. Comparison of variables according to nutritional status

The data shown are represented as mean ± SD. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. A denotes the normal weight group, B denotes the overweight group, and C denotes the obesity group in the post hoc analysis.

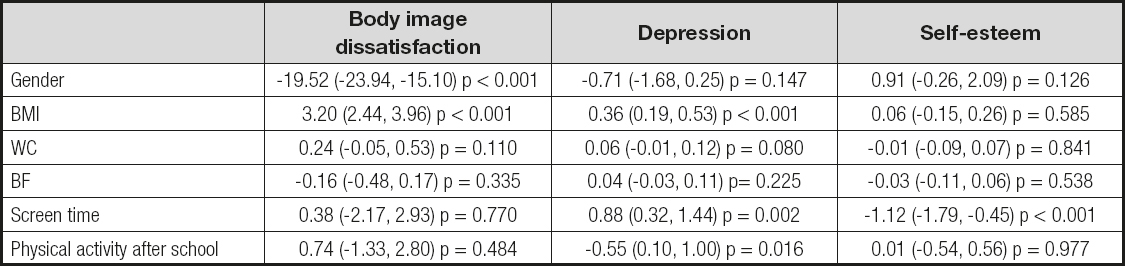

Gender had an association with body image dissatisfaction (β: -19.52, 95% CI: -23.94, -15.10, p < 0.0001). BMI was associated with body image dissatisfaction (β: 3.20, 95% CI: 2.44, 3.96, p < 0.001) and depression (β: 0.36, 95% CI: 0.19, 0.53, p < 0.001). Length of screen time was found to be associated with depression (β: 0.88, 95% CI: 0.32, 1.44, p = 0.002) and inversely associated with self-esteem (β: -1.12, 95% CI: -1.79, -0.45, p < 0.001). After-school PA was found to be inversely associated with depression (β: -0.55, 95% CI: 0.10, 1.00, p = 0.016) (Table V).

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to compare levels of psychological well-being, as reflected in self-esteem, body image and depression, between groups of schoolchildren according to PA patterns (consisting of screen time, after-school PA and weight status).

The schoolchildren with higher screen time and lower after-school PA reported worse psychosocial well-being than their counterparts. Moreover, screen time duration was positively associated with depression and inversely associated with self-esteem. These findings are consistent with another investigation that also found an association between excessive screen exposure and poor psychosocial well-being in children (5). Likewise, screen time – in particular, watching television – has been negatively associated with the development of physical and cognitive abilities and positively associated with obesity, sleep problems, depression and anxiety (6). Along these lines, the evidence shows small but consistent associations between screen time and poor mental health (7). A study reported that children and adolescents who spent more time using screens showed worse psychological well-being than low-screen time users (34). Moreover, increased sedentary time is associated with more peer problems in children whereas PA, generally, is beneficial for peer relations in children (35).

In our sample, psychological well-being was lower in the obese group than in the normal-weight group; furthermore, BMI levels were associated with body image dissatisfaction and depression. A study of Australian students of a similar age found that obesity affects the self-perception of children, particularly girls, during early adolescence (36). Hesketh et al. (37) reported that children who were overweight or obese at 5-10 years of age had lower self-esteem when compared to non-overweight children. Moreover, a previous investigation indicated that children with adiposity were more likely to report higher body dissatisfaction (38). An investigation reported that overweight/obese children (aged 6-13 years) were significantly more likely to suffer from depression than normal-weight children (39). A study of Korean schoolchildren found that obese children with higher body dissatisfaction had lower self-esteem and more depressive symptoms than normal-weight children (17). In children, a differential effect of obesity on self-esteem has been observed in problems of externalization and social perception related to bullying behaviors (40).

In the present study, after-school PA was inversely associated with depression. In this sense, the evidence indicated that low PA levels are associated with poor psychological well-being (41,42). These associations are worrisome, as we found that PA levels were lower in obese students than in overweight and normal-weight schoolchildren. These associations imply that obese children are at greater risk of a depressive episode or symptoms of depression (43). The literature suggests that higher levels of PA can help reduce symptoms of depression in childhood (44,45), which is accompanied by changes in self-esteem (46). Likewise, the evidence suggests that daily TV watching in excess of 2 hours is associated with reduced psychosocial health (47).

LIMITATIONS

This study has some limitations. Although we used standardized PA questionnaires, we did not use accelerometer devices, which would have provided a more precise quantification of PA patterns and sedentary behaviour. The strengths of this study are that we examined several variables that affect the academic performance and mental health of children, contributing to a better understanding of the serious problem of excessive screen time, physical inactivity, and childhood obesity. The information available regarding the psychological well-being in obesity children is important, especially for professionals in the Nutrition and Physical Activity Sciences, given the current study provides some insights into this field.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, schoolchildren with bad PA patterns such as higher screen time per day, lower after-school PA, and obesity status presented poor psychological well-being compared to their peers with good PA levels and normal weight status. Moreover, screen time duration, after-school PA, and BMI were associated with psychological well-being (i.e., in terms of depression, body image, and self-esteem). This suggests that prevention strategies for childhood sedentary behaviour need to begin early in order to minimize its psychological impact during adolescence and adulthood.