Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Anales de Psicología

versión On-line ISSN 1695-2294versión impresa ISSN 0212-9728

Anal. Psicol. vol.33 no.3 Murcia oct. 2017

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.33.3.269211

Multiple Mediation of Loneliness and Negative Affects in the Relationship between Adolescents' Social Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms

Mediación múltiple de la soledad y las afecta negativas en la relación entre la ansiedad social de los adolescentes y los síntomas depresivos

Kemal Baytemir1 and Mehmet Ali Yıldız2

1 Amasya University (Turkey).

2 Adiyaman University (Turkey).

ABSTRACT

The current research aims to investigate the multiple mediation of loneliness and negative affects in the relationship between adolescents' social anxiety and depressive symptoms. Study participants, selected through convenience sampling, consisted of a total of 263 students, including 155 females (59%) and 108 males (41%), attending various high schools in a city in the mid Black Sea Region. Participant students' ages ranged between 14 and 18, with an average age of 15.05 (SD=.90). Data for the current study were collected through the Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents, UCLA Loneliness Scale - Short Form, Positive and Negative Affect Schedule for Adolescents, Depression Scale for Children, and Personal Information Form. Current research data were analyzed through descriptive statistics, Pearson correlation coefficient, and an approach based on Ordinary Least Squares Regression, and the Bootstrap Method. The current study findings indicated that loneliness and negative affects, both separately and together, mediated the relationship between social anxiety and depressive symptoms. No significant difference was found in the comparison conducted to reveal the more powerful mediating variable in terms of mediation effect. In addition, it was found that the model overall was significant and it explained 44% of the total variance in depressive symptoms. A discussion about and interpretation of findings obtained in the current study were included along with suggestions for relevant practitioners.

Key words: Social anxiety; depressive symptoms; loneliness; negative affects; multiple mediation; adolescents.

RESUMEN

La presente investigación tiene como objetivo investigar la mediación múltiple de la soledad y de los afectos negativos en la relación entre la ansiedad social y los síntomas depresivos de los adolescentes. Los participantes del estudio, seleccionados mediante muestreo por conveniencia, fueron un total de 263 estudiantes, incluyendo a 155 mujeres (59%) y 108 hombres (41%), que asistían a varias centros de educación secundaria en una ciudad de la región del Mar Negro. La edad de alumnos participantes osciló entre 14 y 18 años, con una edad promedio de 15.05 (SD = 0.90). Los datos para este estudio fueron recolectados de la Escala de Ansiedad Social para Adolescentes, Escala de Soledad (Abreviado) UCLA, Registro de afecto positivo y negativo para Adolescentes, Escala de Depresión para Niños y formulario de información personal. Los datos se analizaron mediante estadística descriptiva, coeficiente de correlación de Pearson, y un enfoque basado en regresión de mínimos cuadrados ordinarios, y el método de Bootstrap. Los hallazgos del estudio indican que la soledad y los afectos negativos, tanto por separado como en conjunto, median en la relación entre la ansiedad social y síntomas depresivos. No se encontraron diferencias significativas en la comparación llevada a cabo para encontrar variables mediadoras más potentes en términos de efecto de la mediación. Además, se encontró que el modelo globalmente fue significativo y explicó el 44% de la varianza total en los síntomas depresivos. Se incluye una discusión sobre la interpretación de los resultados obtenidos en el presente estudio junto con sugerencias para los profesionales pertinentes.

Palabras clave: Ansiedad social; síntomas depresivos; soledad; afectos negativos; mediación múltiple; adolescentes.

Introduction

Adolescence covers a period when efforts for independence and autonomy demands increase (Temel & Aksoy, 2001), beginning with puberty, continuing to adulthood, and consisting of a transitory period between childhood and adulthood (Yazgan, İnanç, Bilgin & Kılıç-Atıcı, 2012). Adolescence is a period of biological, psychological, social, and economic transitions (Steinberg, 2007). Even though adolescence is not always turbulent, it is a period when physical, cognitive, social, and emotional changes are experienced intensely. Adolescence is also a critical period in terms of social change in close friendships, romantic relationships, and social network expansion. The relationships between these important changes in adolescents' social encounters and various aspects of mental health have been investigated by many. It is important that depression and anxiety in particular are studied in adolescence (La Greca & Harrison, 2005). Social anxiety and depression are the two most widely encountered psychological disorders (Davidson, Wingate, Grant, Judah & Mills, 2011), very often accompanying each other, as common mental health problems among adolescents (Hamilton et al., 2016; Klemanski, Curtiss, McLaughlin & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2016; La Greca, Ehrenreich-May, Mufson & Chan, 2016). High levels of social anxiety are common between the ages of 10 and 19. The prevalence of social anxiety disorder was 11% and that of depression was 27% in the study conducted by Beesdo et al. (2007). Stein et al. (2001) found the prevalence of social anxiety in adolescents to be 7.2% and Mehtalia & Vankar (2004) found it to be 12.8% in their study. Social anxiety disorder, encountered during pre-adolescence, increases the risk for depression (Beesdo et al., 2007). In addition, adolescents with social anxiety are three times more likely to exhibit depressive symptoms for life than those without it (Kessler, Stang, Wittchen, Stein & Walters, 1999). Longitudinal studies indicated that depression may begin around ages 11 - 14 and increase later (Merikangas, Nakamura & Kessler, 2009). A review of studies conducted in Turkey indicates that depression is an important problem among youth (Emiroğlu, Murat & Bindak, 2011; Eskin, Ertekin, Harlak & Dereboy, 2008; Özfirat, Pehlivan & Özdemir, 2009) and, similarly, social anxiety is very prevalent (Gültekin & Dereboy, 2011; Kaya et al., 1997). Thus, social anxiety and depression seem to be important issues for youth in Turkey.

Ollendick & Yule (1990) found that children with high levels of depression had high levels of social evaluation fear and anxiety, as well. Many studies showed that social anxiety accompanied depression and it was one of the important predictors of depression (Beesdo et al., 2007; Davidson et al., 2011; Gültekin & Dereboy, 2011; Horn & Wuyek, 2010; Ottenbreit, Dobson & Quigley, 2014; Stein et al., 2001; Hamilton et al., 2016; Kessler et al., 1999; Kocabaşoğlu, Doksat & Doğanğun, 2004; Mehtalia & Vankar, 2004; Nepon, Flett, Hewitt & Molnar, 2011; Ohayon & Schatzberg, 2010).

Individuals with high levels of social anxiety, thinking that their actions will be considered inadequate, feel embarrassed in social environments and they have excessive and constant feelings of fear (Türkçapar, 1999). Social anxiety is prevalent and peaks in adolescence and is associated with various mental disorders (Masia-Warner et al., 2005). Avoiding social environments gradually increases from the beginning to the end of adolescence and there is a significant relationship between avoiding social environments and social anxiety (Miers, Blöte, Heyne & Westenberg, 2014). Individuals with social anxiety are observed to encounter problems in academic issues, peer relationships, and social skills (Aydin & Tekinsav-Sütcü, 2007; Beidel, Turner & Morris, 1999; Ginsburg, La Greca & Silverman, 1998; Greco & Morris, 2005; Khalid-Khan, Santibanez, McMicken & Rynn, 2007; La Greca & Lopez, 1998; Spence, Donovan & Brechman-Toussaint, 1999), to experience attachment problems (Bayramkaya, 2010), and to have self-destructive thoughts and low quality of life (Gültekin & Dereboy, 2011).

In adolescence, building new relationships with peers of both genders, achieving an appropriate social role, feeling belongingness to a community, becoming emotionally independent, initiating relationships with adults and being accepted by them are among the psycho-social development tasks to be achieved (Gander & Gardiner, 2004; Havighurst, 1947). Social anxiety is likely to inhibit the development and sustainment of positive peer relationships in childhood and adolescence. Peer rejection is associated with social withdrawal, behavior inhibition, and anxiety. In addition, negative experiences with peers and lack of self-confidence in an individual's skills may lead to social anxiety and social withdrawal (Inderbitzen, Walters & Bukowski, 1997). Su, Pettit & Erath's (2016) study on adolescents showed that adolescents rejected by friends and less guided by families experienced more social anxiety. Individuals with high levels of social anxiety have been observed to avoid social environments and to have difficulties initiating and sustaining friendships. Children with social anxiety have been found to experience problems with peers and to prefer to be alone (Bernstein, Bernat, Davis & Layne, 2008). In relevant studies, social anxiety, similarly, is found to be significantly associated with loneliness (Johnson, Lavoie & Mahoney, 2001; Sübaşi, 2007). Again, Lim, Rodebaugh, Zyphur & Gleeson's (2016) study showed that, in six months, the social anxiety measured in the first months significantly predicted the loneliness measured later. Another study (Ebesutani et al., 2015), loneliness was found to mediate between anxiety and loneliness both in a clinical sample consisting of children and youth and in a regular population consisting of children and youth. Researchers (Ebesutani et al., 2015) particularly emphasized that loneliness had a significant relationship with anxiety and increased the depression risk. Lonely individuals experience more anxiety about being unwanted by others in interpersonal interactions. They think about themselves negatively, particularly in social spheres (Wilbert & Rupert, 1986).

Lonely individuals experience more negative and fewer positive affects (van Roekel et al., 2013). According to Moore & Schultz (1983), adolescence years consist particularly of an important developmental period of life because the feeling of loneliness is most widely-encountered in this time (Heinrich & Gullone, 2006). Moore & Schultz (1983), in their study on adolescents, found that loneliness was positively related to anxiety, depression, external locus of control, and social anxiety and negatively related to life satisfaction, happiness, attractiveness, and friendliness. According to the researchers, loneliness may be associated with low levels of social risk taking and social anxiety, and lack of social skills may be a symptom of loneliness or a leading factor in loneliness. Santrock (2011) stated that adolescents who are rejected by their peers, with no close relationships and inadequate communication with friends, had increasing inclinations towards depression. Significant relationships between loneliness and depression were found in many studies (Hsu, Hailey & Range, 1987; Kim, 2001; Lasgaard, Goossens & Elklit, 2011; Rich & Scovel, 1987; Swami et al., 2007; Qualter, Brown, Munn & Rotenberg, 2010). According to the results of these studies in the relevant literature, lonely individuals are more likely to be depressed.

Depression manifests itself through negative affects, behavioral problems, maladjustment (Lau, Chan & Lau, 1999), and dysfunctional coping styles (Sanjuan & Magallares, 2015). According to Kashdan (2004), depressive symptoms are associated with negative subjective experiences and lack of positive subjective experiences. Similarly, excessive social anxiety is associated with low levels of positive affects and high levels of negative affects. Lim, Rodebaugh, Zyphur & Gleeson's (2016) study showed that, in six months, the loneliness measured in the first months significantly predicted the depression measured later. Vittengl & Holt (1998) stated that individuals with social anxiety often experienced fewer positive and more negative emotions. This mood state can be associated with low quality communication or being disturbed by social evaluations in interactions with nonacquaintances. In the researchers' study, it was found that individuals with high levels of social anxiety experienced more negative emotions than individuals with low levels of social anxiety did. Thus, individuals with depression and anxiety experience more negative emotions. In another study, adolescents experiencing more social anxiety and depression were found to have decreased emotional awareness and difficulties expressing and managing emotions (Klemanski, Curtiss, McLaughlin & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2016). As can be seen, depressive and anxious individuals experience more negative emotions and find it difficult to regulate their emotions. The threefold structure suggested by Clark & Watson (1991) included some common aspects, such as anxiety and depression, disturbance and negative emotions; however, it differs with physiological stimulation in anxiety and lack of positive emotions in depression.

According to the above studies from the relevant literature and theoretical information, social anxiety, loneliness, negative affects, and depressive symptoms are directly interrelated concepts. Particularly when social anxiety and depressive symptoms are considered to be closely related and accompanying each other, it may be important to investigate the mediation role of loneliness and negative affects that could impact the relationships between these variables. This is because social anxiety may be increasing adolescent depression leading to loneliness and negative affects. Defining these relationships may contribute to protective and preventive intervention studies on adolescents. Thus, the suggested model in Figure 1 is included in the current research.

As can be seen in Figure 1, based on the relevant literature review, social anxiety, depressive symptoms, loneliness, and negative affects in adolescents are predicted to be interrelated. Hence, in the current research, both serial and separate mediation roles of loneliness and negative affects in the relationship between social anxiety and depressive symptoms were investigated.

Method

Participants

Research participants, selected through convenience sampling, consisted of a total of 263 students, including 155 females (59%) and 108 males (41%), attending three different Anadolu high schools in a city in the mid Black Sea Region. Participant students' ages ranged between 14 and 18, with an average age of 15.05 (SD= .90).

Measures

Social Anxiety Scale forAdolescents (SASA): The Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents was developed by La Greca & Lopez (1998) to measure the social anxiety levels of adolescents. Adaptation studies of the SASA into the Turkish language were conducted by Aydin & Tekinsav-Sutcu (2007). SASA validity and reliability studies included 1242 adolescents (643 females and 599 males) between the ages of 12 and 15. The SASA is a 5-point Likert-type scale with a minimum score of 18 and maximum obtainable score of 90. There are three sub-scales available on the SASA: Fear of Negative Evaluation (FNE), General Social Avoidance and Emotional Distress (G-SAED), and Social Avoidance and Emotional Distress in Unfamiliar Situations (SAED-US). Internal consistency values calculated for SASA reliability were between .66 and .91. Among the sub-scales, correlation values were found to be .52 and .71. In the current study, the internal consistency coefficient was .90.

UCLA Loneliness Scale - Short Form (ULS-8): The UCLA Loneliness Scale - Short Form was developed by Hays & DiMatteo (1987). Adaptation studies of the ULS-8 into the Turkish language were conducted by Yıldız & Duy (2014). Results of the explanatory factor analysis conducted for ULS-8 construct validity showed that the adapted scale was single-dimensional, as in the original form. Factor load values of the scale were stated to range between .31 and .71. ULS-8 fit values were found to be χ2=27.12, df=14, χ2/df=1.94, RMSEA=.06, RMR=.03, SRMR=.04, GFI=.97, AGFI=.95, CFI=.98, NFI=.96, and NNFI=.97 through confirmatory factor analysis. In the analyses conducted for ULS-8 criterion validity, significant-level relationships, as expected, between loneliness and general belonging (-.71) and loneliness and life satisfaction (-.42) were found. The Cronbach's alpha internal consistency coefficient of the ULS-8 was stated to be a=.74. The scale composite reliability was .75 and average variance extracted value was .40. The ULS-8 test-retest reliability coefficient, with a two-week interval, was stated as .84 (Yıldız & Duy, 2014). In the current study, the internal consistency coefficient was found to be .68.

Positive and Negative Affect Schedule for Adolescents (PANAS-A): The PANAS-A, developed by Laurent et al. (1999), was adapted into the Turkish language by Yıldız (2014). A short form of the scale was created based on the analyses conducted. The scale has 14 items, including 7 positive affects and 7 negative affects. In Yıldız's (2014) study, measurement invariance for genders was provided. The fit values based on the confirmatory factor analysis were stated as follows: χ2=164.63, df=76, χ2/df=2.17, RMSEA=.06, SRMR=.05, GFI=.93, AGFI =.90, and CFI=.98. Cronbach's alpha values calculated for the scale's internal consistency were found to be .91 for positive affects and .79 for negative affects. In addition, the PANAS-A composite reliability values were found to be .91 for negative affects and .79 for positive affects, as well as average variance extracted values of .76 for positive affects and .46 for negative affects. The scale test-retest reliability with a three-week interval was .70 for positive affects and .63 for negative affects. In the scale validity study, the PANAS-A was found to exhibit a significant relationship between life satisfaction and depressive symptoms (Yıldız, 2014). In the current research, the negative affect sub-scale of the PANAS-A was used and its internal consistency coefficient was found to be .79.

Children's Depression Inventory (CDI): The CDI was developed by Kovacs (1985) and the adaptation studies of the CDI into Turkish language were conducted by Öy (1991). For the scale validity, 59 randomly selected students from every grade level were interviewed about depression and the Childhood Depression Rating Scale was applied. Depression diagnosis was based on DSM III criteria. Thus, scale sensitivity was found to be at the 60% level for children with major depression and depressive symptoms. For these students, the correlation between the total scores of the CDI and Childhood Depression Rating Scale was .61. CDI test-retest reliability with a one-week interval was stated to be .80 (Öy, 1991). In the current study, the scale internal consistency coefficient was found to be .82.

Personal Information Form. The form was constructed by the researchers to determine the students' grade levels, genders, and ages.

Procedure

Upon obtaining required permission from the Department of Education, researchers collected data on adolescents attending various high schools. Measures were applied on a voluntary basis; those volunteering to participate in the current study were briefly given information assuring that the research had nothing to do with their classes and the data collected would not be used for any purpose other than the current research. Data collection lasted approximately 20 minutes. Descriptive analyses and Pearson correlation coefficient were used for the data analyses. The statistical significance of the mediation effects in the serial mediation model tested in the current study was examined through PROCESS software developed by Hayes (2012; 2013), an approach based on ordinary least squares regression and the Bootstrap Method. In the current study, 10000 Bootstrap samples were used for mediation analyses. Bootstrap analyses in the current research were conducted through PROCESS Macrobased Multiple Mediation Model 6. The significance level for the current study was set at .05. The IBM SPSS 22.0 software package was used in the current research for data analyses.

Results

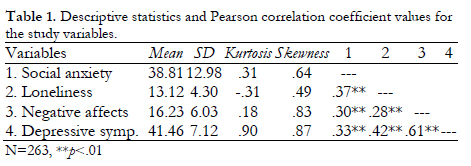

Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to define the relationships among social anxiety, loneliness, negative affect, and depressive symptoms. Findings obtained and descriptive statistics are included in Table 1.

A review of the values in Table 1 indicates that the kurtosis and skewness values of all variables in the current study range between +1 and -1; thus, distribution of the data was at normal levels (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013). Results of the correlation analysis indicated positive mid-level significant relationships between social anxiety and loneliness and negative affects and depressive symptoms. In addition, positive significant relationships, at low and mid-levels, were found between loneliness and negative affects and depressive symptoms. Also, a high-level, positive significant relationship between negative affects and depressive symptoms was found. Figure 2 includes the results associated with the serial mediation of loneliness and negative affects in the relationship between social anxiety and depressive symptoms.

A review of Figure 2 indicated a significant-level total effect (c=.18, SE=.03, t=5.59, p<.001) of social anxiety on depressive symptoms (Step 1). The direct effects of social anxiety on loneliness (B=.12, SE=.02, t=6.40, p<.001) and negative affects (B=.11, SE=.03, t=3.61, p<.001), as mediating variables, were also significant. The direct effect of loneliness, as the first mediating variable, on negative affects (B= .27, SE= .09, t=2.97, p<.001), as the second mediating variable, was also significant (Step 2). A review of the direct effects of mediating variables on depressive symptoms indicated that the effects of loneliness (B=.37, SE=.08, t=4.40, p<.001) and negative affects (B=.61, SE=.06, t=10.54, p<.001) were also statistically significant (Step 3). The relationship between social anxiety and depressive symptoms was not found to be significant (c'=.05, SE=.03, t=1.73, p>.05) in terms of the direct effect when social anxiety and both mediating variables were simultaneously entered into the equation (Step 4). Such results indicate that mediating variables mediate between social anxiety and depressive symptoms. In addition, it was found that the model overall showed significant levels (F(4-258)=50.59, p<.001) and explained 44% of the variance in depressive symptoms. Table 2 includes a comparison of direct and specific indirect effects of adolescents' social anxiety on depressive symptoms, through loneliness and negative affects.

The statistical significance of the indirect effects in the model tested in the current research was examined on 10000 bootstrap samples. Estimates were taken within a 95% confidence interval, and bias-corrected and accelerated results are presented in Table 2. Table 2 indicates that the total indirect effect (namely, the difference between the total and in direct effect /c-c') of social anxiety on depressive symptoms through loneliness and negative affects was statistically significant (point estimate=.1292 and 95% BCa CI [.0813, .1843]). The single mediation of loneliness (point estimate=.0450 and 95% BCa CI [.0234, .0761]), multiple serial mediation (point estimate=.0197 and 95% BCa CI [.0046, .0427]) of loneliness and negative affects, and the single mediation of negative affects (point estimate=.0644 and 95% BCa CI [.0214, .1127]) were found to be statistically significant when the mediating variables were examined separately and together in terms of mediation within the indirect effects of social anxiety on depressive symptoms in the tested model.

Contrasting findings, given in pairs in order to ascertain whether specific indirect effects of some mediating variables were stronger than those of others in the current study, are presented in Table 2. Based on the current study results, three separate contrasting pairs were obtained. Thus, the point estimate of multiple serial mediation of loneliness and negative affects and the point estimate of single mediation of negative affects were found to be within the 95% BCa confidence interval; these mediation models were not considered statistically different from one another in terms of mediation power. In other words, mediating variables did not differ in relation to mediating power.

Discussion and Conclusion

The current research investigated the mediating roles of loneliness and negative affects in the relationship between adolescents' social anxiety and depression. The current study results indicated that the predictor variable of social anxiety predicted depression, loneliness, and negative affects. Loneliness, one of the mediating variables, predicted negative affects, another mediating variable. Both mediating variables predicted depression, an outcome variable. Mediation analysis showed no significant direct relationship between social anxiety as the predictor variable and depression as the outcome variable. Thus, it may be said that mediating variables mediated between social anxiety and depressive symptoms. In addition, it was found that the model overall showed significant levels and explained 44% of the total variance in depressive symptoms. The comparison conducted to determine what mediating variable was stronger than the others in terms of mediation effect did not indicate any significant difference. Hence, it can be concluded that the mediating effects of both loneliness and negative affects and the effects of multiple serial mediation of both variables between social anxiety and depression were within a close range.

The current study results seemed consistent with those in the relevant literature. In some studies, social anxiety was found to predict depression (Beesdo et al., 2007; Davidson et al., 2011; Gültekin & Dereboy, 2011; Horn & Wuyek, 2010; Kocabaşoğlu, Doksat & Doğangün, 2004; Ottenbreit et al., 2014; Stein et al., 2001). This result is overwhelmingly supported in the relevant literature; adolescents with high levels of social anxiety avoid social environments as they think their behaviors would be considered worthless and inadequate (Türkçapar, 1999).

Problems of youth embarrassed to meet new people and unable to develop meaningful relationships with the people meet are likely to increase. Thus, social anxiety not only presents itself in ordinary daily challenges but can also lead to serious issues such as suicide (Sübaşi, 2007). Adolescents with high levels of social anxiety may feel inadequate about social interactions; thus, they may experience loneliness and negative affects that lead to feelings of guilt along with depressive symptoms. In addition, individuals with social anxiety may feel badly and be depressed each time they experience anxiety in social environments. When they are unable to cope with the anxiety, they may suffer learned helplessness due to dysfunctional thinking and their depression will continue.

That social anxiety predicts loneliness and negative affects is consistent with the findings of studies in the relevant literature (Johnson et al., 2001; Lim, Rodebaugh, Zyphur, Gleeson, 2016; Sübaşı, 2007; van Roekel et al., 2013). Adolescents with high levels of social anxiety may avoid social environments through avoidance methods and when experiencing problems socializing with peers, be depressed due to loneliness and negative emotions. Adolescence is a time when social anxiety and loneliness in particular are intensely experienced. Adolescents with social anxiety may prefer loneliness because they think that they are unwanted and evaluated negatively by others. When adolescents in much need of peer support are rejected by their peers, they experience more social anxiety (Su, Pettit & Erath, 2016).When the emphasis on peer relationships during adolescence is taken into account, an adolescent is likely to experience loneliness and negative affects upon being unable to initiate and sustain relationships. On the other hand, adolescents with high levels of social anxiety may feel lonely upon thinking that this situation will not change for the better as they often experience anxiety. Many studies showed that individuals with high levels of social anxiety experienced more negative affects than those with low levels of social anxiety did and were unable to functionally regulate their emotions (Contardi et al., 2012; Klemanski, Curtiss, McLaughlin & Nolen-Hoeksema 2016; Rusch, Westermann & Lincoln, 2012; Turk, Heimberg, Luterek, Mennin & Fresco, 2005). According to Eisner, Johnson & Carver (2009), individuals with social anxiety may try to lessen their anxiety about their looks, intensely experienced in social environments, by suppressing these feelings. Similarly, Werner, Goldin, Ball, Heimberg & Gross (2011) found that individuals with social anxiety avoided regulation their affects and, instead of showing their feelings, they suppressed them. These individuals felt less selfconfident about cognitive re-evaluation. Similarly, Klemanski, Curtiss, McLaughlin & Nolen-Hoeksema (2016) found that adolescents experiencing more social anxiety and depression had less emotional awareness and difficulties expressing and managing their emotions. Based on the findings of the current research, it may be concluded that adolescents with social anxiety have feelings of loneliness and negative affects due to difficulties regulating emotions about their anxiety and, thus, experience depressive symptoms.

Loneliness as a predictor of depression is consistent with the results of previous research in the literature (Hsu, Hailey & Range 1987; Kim, 2001; Lasgaard, Goossens & Elklit 2011, Lim, Rodebaugh, Zyphur & Gleeson, 2016). Since loneliness manifests through negative affects, isolation, and maladjustment, it is natural for adolescents to experience depressive symptoms. It is important for adolescents, in terms of feeling good during this period, to be emotionally nourished by peer relationships and to have friends as emotional support (Buhrmester & Furman, 1987). In order for adolescents to adjust properly, they must build close friendships (Buhrmester, 1990). Interacting with other people and socializing can be considered natural inclinations. Baumeister & Leary (1995) stated that people have a basic motivation to build permanent and meaningful interpersonal relationships. Thus, it is reasonable for adolescents who cannot build much-needed close and meaningful relationships with peers to exhibit negative emotions and depressive symptoms.

Thus, the mediation of loneliness and negative affects between social anxiety and depression is consistent with the findings in the literature. It may be considered natural for adolescents with social anxiety to avoid relationships and to experience negative affects since they are unable to fulfill basic needs by building social relationships. As adolescents become lonelier and experience negative affects, they are more likely to have depressive symptoms. An important aspect of both social anxiety and depression is negative affects (Clark & Watson, 1991; Kashdan, 2004). However, depression is an emotional dysregulation. Thus, the mediation role of negative affects can be considered very significant. Social anxiety is associated with the self-evaluation of an individual as someone negative and unwanted. Hence, in Beck's cognitive model (2001), an individual's thoughts in one situation influence the same individual's perception of this situation. This effect is reflected in the situation-specific automatic thoughts and emotions that the individual experiences. This can be understood well when the increase in social anxiety and sensitivity towards being rejected by others, particularly during adolescence, is considered. An individual with high levels of social anxiety is consumed by the idea that others would evaluate him/her negatively in a social environment and this may lead to negative emotions, such as anger and sadness. Similarly, an individual with social anxiety may avoid social environments and prefer loneliness because s/he does not feel comfortable among others and finds social environments difficult. Miers, Blöte, Heyne & Westenberg's (2014) study findings indicated that, towards the end of adolescence, avoiding social environments seemed to increase and there was a significant relationship between avoiding social environments and social anxiety. Preferring loneliness may dissatisfy the need to belong and join in a prominent group; thus, negative affects and depressive symptoms may prevail.

Adolescence should be considered a critical period due to experiences of social anxiety, depression, loneliness, and negative affects. In educational institutions, students who are experiencing high levels of social anxiety and loneliness should be identified and interventions, targeting social anxiety in particular, should be undertaken. Ebesutani et al., (2015) stated that psychological disorders often were not noticed during school years but noticed when an important associated problem occurred; in addition, school staff was incompetent in identifying those psychological disorders. The importance of early intervention has been known for years in psychology literature. Scanning, identifying, referring, and following up with various psychological problems of students during school years will prevent more severe problems in later years from occurring. At this point, particularly mental health experts employed at schools may be notified and their competence may be developed. Cognitive and behavioral interventions to reduce social anxiety and loneliness in groups or for individuals are preferable. Students with high levels of social anxiety may be referred to student clubs that require social interaction, which may provide a basis for them to cope with social anxiety. In addition, for students experiencing negative affects intensely as well as the inability to regulate their emotions, both group and individual interventions about functionally regulating emotions may be planned. In further studies, emotion regulation strategies as a mediating variable may be tested. Also, the effects of variables such as perceived social support, belongingness, and self-competence on the relationships between social anxiety and depressive symptoms may be investigated.

The current study had some limitations. First, as the participants were not known to have any clinical problems, all students were considered to have no mental problems at the clinical level. Second, considering cultural differences are important, particularly in terms of their effects on social anxiety, the generalizability of the current study findings may be deemed limited because the sample was drawn in one city within one region.

References

1. Aydın, A., & Tekinsav-Sütcü, S. (2007). Ergenler için sosyal kaygi ölçeğinin (ESKÖ) geçerlik ve güvenirliğinin incelenmesi (Validity and reliability of social anxiety scale for adolescents (SAS-A)). Turkish Journal of Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 14(2), 79-89. [ Links ]

2. Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 497-529. [ Links ]

3. Bayramkaya, E. (2010). Sosyal fobi belirtileri, yetişkin bağlanma boyutlari ve kişilerarasi ilişki tarzlari arasindaki ilişkiler (The relationship between social phobia symptoms, adult attachment styles and interpersonal relationships styles). 16. Ulusal Psikoloji Kongresi 14-17 Nisan, Mersin. [ Links ]

4. Beesdo, K., Bittner, A., Pine, D. S., Stein, M. B., Höfler, M., Lieb, R., & Wittchen, H. U. (2007). Incidence of social anxiety disorder and the consistent risk for secondary depression in the first three decades of life. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64(8), 903-912. [ Links ]

5. Beck, J. S. (2011). Cognitive behavior therapy: Basics and beyond. New York: The Guilford Press. [ Links ]

6. Beidel, D. C., Turner, S. M., & Morris T. L. (1999). Psychopathology of childhood social phobia. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 38(6), 643-650. [ Links ]

7. Bernstein, G. A., Bernat, D. H., Davis, A. A, & Layne, A. E. (2008). Symptom presentation and classroom functioning in a nonclinical sample of children with social phobia. Depression and Anxiety, 25, 752-760. [ Links ]

8. Buhrmester, D. (1990). Intimacy of friendship, interpersonal competence, and adjustment during preadolescence and adolescence. Child Development, 61(4), 1101-1111. [ Links ]

9. Buhrmester, D., & Furman, W. (1987). The development of companionship and intimacy. Child Development, 58(4), 1101-1113. [ Links ]

10. Clark, L. A., & Watson, D. (1991). Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: Psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100(3), 316-336. [ Links ]

11. Contardi, A., Farina, B., Fabbricatore, M., Tamburello, S., Scapellato, P., Penzo, I., ... & Innamorati, M. (2012). Difficulties in emotion regulation and personal distress in young adults with social anxiety. Rivista di Psichiatria, 48(2), 155-161. [ Links ]

12. Davidson, C. L., Wingate, L. R., Grant, D. M., Judah, M. R., & Mills, A. C. (2011). Interpersonal suicide risk and ideation: The influence of depression and social anxiety. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 30(8), 842-855. [ Links ]

13. Ebesutani, C., Fierstein, M., Viana, A. G., Trent, L., Young, J., & Sprung, M. (2015). The role of loneliness in the relationship between anxiety and depression in clinical and school-based youth. Psychology in the Schools, 52(3), 223-234. [ Links ]

14. Eisner, L. R., Johnson, S. L., & Carver, C. S. (2009). Positive affect regulation in anxiety disorders. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 23(5), 645-649. [ Links ]

15. Emiroğlu, M., Murat, M., & Bindak, R. (2011). Lise son sinif öğrencilerinin depresyon düzeylerini yordayan sosyo-demografik değişkenlerin belirlenmesi (Determination of socio-demographic variables predicting levels of high school students). Electronic Journal of Social Sciences, 10(38), 262-274. [ Links ]

16. Eskin, M., Ertekin, K., Harlak, H., & Dereboy, Ç. (2008). Lise ğrencisi ergenlerde depresyonun yaygınlığı ve ilişkili olduğu etmenler (Prevalence of and factors related to depression in high school students). Turkish Journal of Psychiatry, 19(4), 382-389. [ Links ]

17. Gander, M. J., & Gardiner, H. W. (2004). (Çocuk ve ergen gelfimi (The development of children and adolescents). (Trans. Ed. B. Onur). (5th ed.) Ankara: Imge Publishing. [ Links ]

18. Ginsburg, G. S., La Greca, A. M., & Silverman, W. K. (1998). Social anxiety in children with anxiety disorders: Relation with social and emotional functioning. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 26, 175-185. [ Links ]

19. Gültekin, B. K., & Dereboy, I. F. (2011). Universite öğrencilerinde sosyal fobinin yaygınlığı ve sosyal fobinin yaşam kalitesi, akademik başarı ve kimlik oluşumu uzerine etkileri (The prevalence of social phobia, and its impact on quality of life, academic achievement, and identity formation in university students). Turkish Journal of Psychiatry, 22(3), 150-158. [ Links ]

20. Greco, L. A., & Morris, T. L. (2005). Factors influencing the link between social anxiety and peer acceptance: Contributions of social skills and close friendships during middle childhood. Behavior Therapy, 36(2), 197-205. [ Links ]

21. Hamilton, J. L., Potter, C. M., Olino, T. M., Abramson, L. Y., Heimberg, R. G., & Alloy, L. B. (2016). The temporal sequence of social anxiety and depressive symptoms following interpersonal stressors during adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44(3), 495-509. [ Links ]

22. Havighurst, R. J. (1947). The developmental tasks of adolescents. UNESCO SummerSeminaron Education for International Understanding, 18 August 1947, (pp. 1-3) Paris, France. Retrieved from: 13. 05. 2016. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/Ulis/cgi-bin/ulis.pl?catno=155680&set= 4EA47322_2_457&gp=&lin=1&ll=f. [ Links ]

23. Hayes, A. F. (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling. Retrieved from: http://processmacro.org/download.html. [ Links ]

24. Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press. [ Links ]

25. Hays, R. D., & DiMatteo, M. R. (1987). A short-form measure of loneliness. Journal of Personality Assessment, 51(1), 69-81. [ Links ]

26. Heinrich, L. M., & Gullone, E. (2006). The clinical significance of loneliness: A literature review. Clinical Psychology Review, 26(6), 695-718. [ Links ]

27. Horn, P. J., & Wuyek, L. A. (2010). Anxiety disorders as a risk factor for subsequent depression. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice, 14, 244-247. [ Links ]

28. Hsu, L. R., Hailey, B. J., & Range, L. M. (1987). Cultural and emotional components of loneliness and depression. The Journal of Psychology, 121(1), 61-70. [ Links ]

29. Inderbitzen, H. M., Walters, K. S., & Bukowski, A. L. (1997). The role of social anxiety in adolescent peer relations: Differences among sociometric status groups and rejected subgroups. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 26(4), 338-348. [ Links ]

30. Johnson, H. D., Lavoie, J. C., & Mahoney, M. (2001). Interparental conflict and family cohesion predictors of loneliness, social anxiety, and social avoidance in late adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Research, 16(3), 304-318. [ Links ]

31. Kashdan, T. B. (2004). The neglected relationship between social interaction anxiety and hedonic deficits: Differentiation from depressive symptoms. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 18(5), 719-730. [ Links ]

32. Kaya, N., Çilli, A. S., Aşkin, R., Herken, H., Özkan, İ., & Kucur, R. (1997). Orta ve yüksekoğrenim öğrencilerinde sosyal fobik belirti yaygınlığı (The prevalence of social phobia among high school and university students). Journal of General Medicine, 7(3), 133-137. [ Links ]

33. Kessler, R. C., Stang, P., Wittchen, H-U, Stein, M., & Walters, E. E. (1999). Lifetime co-morbidities between social phobia and mood disorders in the US National Comorbidity Survey. Psychological Medicine, 29(3), 555-567. [ Links ]

34. Khalid-Khan, S., Santibanez, M-P., McMicken, C., & Rynn, M. A. (2007). Social anxiety disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatric Drugs, 9(4), 227-237. [ Links ]

35. Kim, O. (2001). Sex differences in social support, loneliness, and depression among Korean college students. Psychological Reports, 88(2), 521-526. [ Links ]

36. Klemanski, D. H., Curtiss, J., McLaughlin, K. A., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2016). Emotion regulation and the trans diagnostic role of repetitive negative thinking in adolescents with social anxiety and depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 41(2), 206-219. [ Links ]

37. Kocabaşoğlu, N., Doksat, M. K., & Doğangün, B. (2004). Anksiyete ve depresyonun çök yönlü ilişkisi (Various aspects of relationship between anxiety and depression). Yeni Symposium, 42(4), 168-176. [ Links ]

38. Kovacs, M. (1985). The children's depression inventory (CDI). Psychopharmacology Bulletin, 21(4), 995-998. [ Links ]

39. La Greca, A. M., & Harrison, H. M. (2005). Adolescent peer relations, friendships, and romantic relationships: Do they predict social anxiety and depression? Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 34(1), 49-61. [ Links ]

40. La Greca, A. M., & Lopez, N. (1998). Social anxiety among adolescents: Linkages with peer relationships and friendships. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 26, 83-94. [ Links ]

41. La Greca, A. M., Ehrenreich-May, J., Mufson, L., & Chan, S. (2016). Preventing adolescent social anxiety and depression and reducing peer victimization: Intervention development and open trial. Child & Youth Care Forum, 45(6), 905-926. [ Links ]

42. Lasgaard, M., Goossens, L., & Elklit, A. (2011). Loneliness, depressive symptomatology, and suicide ideation in adolescence: Cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39(1), 137-150. [ Links ]

43. Lau, S., Chan, D. W., & Lau, P. S. (1999). Facets of loneliness and depression among Chinese children and adolescents. The Journal of Social Psychology, 139(6), 713-729. [ Links ]

44. Lim, M. H., Rodebaugh, T. L., Zyphur, M. J., & Gleeson, J. F. (2016). Loneliness over time: The crucial role of social anxiety. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 125(5), 620-630. [ Links ]

45. Laurent, J., Catanzaro, S. J., Joiner Jr, T. E., Rudolph, K. D., Potter, K. I., Lambert, S., ... & Gathright, T. (1999). A measure of positive and negative affect for children: scale development and preliminary validation. Psychological Assessment, 11(3), 326-338. [ Links ]

46. Masia-Warner, C., Klein, R. G., Dent, H. C., Fisher, P. H., Alvir, J., Albano, A. M., & Guardino, M. (2005). School-based intervention for adolescents with social anxiety disorder: Results of a controlled study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 33(6), 707-722. [ Links ]

47. Mehtalia, K., & Vankar, G. K. (2004). Social anxiety in adolescents. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 46(3), 221-227. [ Links ]

48. Merikangas, K. R., Nakamura, B. A., & Kessler, R. C. (2009). Epidemiology of mental disorders in children and adolescents. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 11(1), 7-20. [ Links ]

49. Miers, A. C., Blöte, A. W., Heyne, D. A., & Westenberg, P. M. (2014). Developmental pathways of social avoidance across adolescence: The role of social anxiety and negative cognition. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 28(8), 787-794. [ Links ]

50. Moore, D., & Schultz Jr, N. R. (1983). Loneliness at adolescence: Correlates, attributions, and coping. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 12(2), 95-100. [ Links ]

51. Nepon, T., Flett, G. L., Hewitt, P. L., & Molnar, D. S. (2011). Perfectionism, negative social feedback, and interpersonal rumination in depression and social anxiety. Canadian Journal of Behavioral Science, 43(4), 297-308. [ Links ]

52. Ohayon, M. M., & Schatzberg, A. F. (2010). Social phobia and depression: Prevalence and comorbidity. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 68(3), 235-243. [ Links ]

53. Ollendick, T. H., & Yule, W. (1990). Depression in British and American children and its relation to anxiety and fear. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 58(1), 126-129. [ Links ]

54. Ottenbreit, N. D., Dobson, K. S., & Quigley, L. (2014). An examination of avoidance in major depression in comparison to social anxiety disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 56, 82-90. [ Links ]

55. Öy, B. (1991). Çocuklar için depresyon ölçeği: Geçerlilik ve güvenirlik çalışması (Depression scale for children: Validity and reliability study). Turkish Journal of Psychiatry, (2), 132-136. [ Links ]

56. Özfirat, Ö., Pehlivan, E., & Özdemir, F. Ç. (2009). Malatya il merkezindeki lise son sinif öğrencilerinde depresyon prevalansı ve ilişkili faktörler (The depression prevalence and related factors in the last-phase highschool students in the Centre of Malatya). Journal of Inonu University Medical Faculty, 16(4), 247-255. [ Links ]

57. Rich, A. R., & Scovel, M. (1987). Causes of depression in college students: A cross-lagged panel correlational analysis. Psychological Reports, 60(1), 27-30. [ Links ]

58. Rusch, S., Westermann, S., & Lincoln, T. M. (2012). Specificity of emotion regulation deficits in social anxiety: An internet study. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 85(3), 268-277. [ Links ]

59. Sanjuan, P., & Magallares, A. (2015). Coping strategies as mediator variables between explanatory styles and depressive symptoms. Anales de Psicologta/Annals of Psychology, 31(2), 447-451. [ Links ]

60. Santrock, J. W. (2011). Yaşam boyu gelişim (Life-span development). (Trans. Ed. G.Yüksel). Ankara: Nobel Publishing. [ Links ]

61. Spence, S. H., Donovan, C., & Brechman-Toussaint, M. (1999). Social skills, social outcomes, and cognitive features of childhood social phobia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 108(2), 211-221. [ Links ]

62. Stein M. B., Fuetsch, M., Muller, N., Hofler, M., Lieb, R., & Wittchen, H-U. (2001). Social anxiety disorder and the risk of depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 58, 251-256. [ Links ]

63. Steinberg, L. (2007). Ergenlik (Adolescence). (Trans. Ed. F. Çok). (First ed.). Ankara: Imge Publishing. [ Links ]

64. Su, S., Pettit, G. S., & Erath, S. A. (2016). Peer relations, parental social coaching, and young adolescent social anxiety. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 42, 89-97. [ Links ]

65. Sübaşı, G. (2007). Üniversite öğrencilerinde sosyal kaygıyı yordayıcı bazı değişkenler (Some variables for social anxiety prediction in college students). Education and Science, 32, 3-15. [ Links ]

66. Swami, V., Chamorro-Premuzic, T., Sinniah, D., Maniam, T., Kannan, K., Stanistreet, D., & Furnham, A. (2007). General health mediates the relationship between loneliness, life satisfaction and depression. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 42(2), 161-166. [ Links ]

67. Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2013). Using multivariate statistics (6th Ed.). Boston: Pearson. [ Links ]

68. Temel, Z. F., & Aksoy, A. B. (2001). Ergen vegeliyimi: Yetiykinlige ilk adim (Adolescents and development: The first step to adulthood). (First ed.). Ankara: Nobel Publishing. [ Links ]

69. Turk, C. L., Heimberg, R. G., Luterek, J. A., Mennin, D. S., & Fresco, D. M. (2005). Emotion dysregulation in generalized anxiety disorder: A comparison with social anxiety disorder. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 29(1), 89-106. [ Links ]

70. Türkçapar, M. H. (1999). Sosyal fobinin psikolojik kuramı (Psychological theory of social phobia). Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 2, 247-253. [ Links ]

71. Qualter, P., Brown, S. L., Munn, P., & Rotenberg, K. J. (2010). Childhood loneliness as a predictor of adolescent depressive symptoms: An 8-year longitudinal study. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 19(6), 493-501. [ Links ]

72. van Roekel, E., Goossens, L., Verhagen, M., Wouters, S., Engels, R. C. M. E., & Scholte, R. H. (2013). Loneliness, affect, and adolescents' appraisals of company: An experience sampling method study. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 24(2), 350-363. [ Links ]

73. Vittengl, J. R., & Holt, C. S. (1998). Positive and negative affect in social interactions as a function of partner familiarity, quality of communication, and social anxiety. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 17(2), 196-208. [ Links ]

74. Werner, K. H., Goldin, P. R., Ball, T. M., Heimberg, R. G., & Gross, J. J. (2011). Assessing emotion regulation in social anxiety disorder: The emotion regulation interview. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 33(3), 346-354. [ Links ]

75. Wilbert, J. R., & Rupert, P. A. (1986). Dysfunctional attitudes, loneliness, and depression in college students. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 10(1), 71-77. [ Links ]

76. Yazgan İnanç, B., Bilgin, M., & Kılıç Atıcı, M. (2012). Gelişim psikolojisi: Çocuk ve ergen gelişimi (Developmental psychology: Child and adolescent development). (8th ed.). Ankara: Pegem Academy. [ Links ]

77. Yıldız, M. A. (2014). Ergenlerde anne-babaya bağlanma ile ögnel iyi oluş arasindaki ilişkide duygu düzenleme ve baş etme yöntemlerinin çoklu aracilik rolü (The multiple mediating role of emotion regulation and coping strategies on the relationship between parental attachment and subjective wellbeing in adolescents). Yayimlanmamiş Doktora Tezi (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Mersin University, Mersin, Turkey. [ Links ]

78. Yıldız, M. A., & Duy, B. (2014). Adaptation of the short-form of the UCLA loneliness scale (ULS-8) to Turkish for the adolescents. Düşünen Adam: The Journal of Psychiatry and Neurological Sciences, 27(3), 194-203. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Kemal Baytemir, Ph.D.,

Amasya University,

Faculty of Education,

Department of Psychological Counseling and Guidance,

05000, Amasya (Turkey).

E-mail: kemalbaytemir@hotmail.com

Article received: 27-09-2016

revised: 21-03-2017

accepted: 04-04-2017