Introduction

Orthorexia comes from Greek ortho and orexis, which means “right appetite”. From the same etymological origin of orthorexia, it is clear that an interest in eating right or healthy should not be associated with a problematic approach to food. However, a large part of the scientific literature has focused on the possible pathological aspect of this eating style, which partially overlaps eating behavior disorders and obsessive-compulsive disorders. The vast majority of the studies have used the ORTO-15 (Donini et al., 2005), an instrument that has recently been strongly criticized (Missbach et al., 2015; Roncero, Barrada, & Perpiñá, 2017).

The pathological aspect of orthorexia, orthorexia nervosa (ON), could be conceptualized as extreme or excessive preoccupation with eating food believed to be healthy (Bratman & Knight, 2000; Moroze, Dunn, Holland, Yager, & Weintraub, 2015; Vandereycken, 2011; Varga, Dukay-Szabó, Túry, & van Furth, 2013). People with ON rigidly avoid consuming food because of its content on fats, preservatives, food additives, animal products, or other components considered unhealthy or toxic (Brytek-Matera, 2012). This preoccupation leads them to a life determined by food, which causes impairments in social, familiar, and/or occupational areas. They avoid eating out, and do not wish to interact with others who do not share their beliefs, causing social isolation (Koven & Abry, 2015). They spend excessive amounts of time and money acquiring and preparing specific types of foods based on their perceived quality and composition (Moroze et al., 2015). In some cases, the objective of reaching the “perfect” diet is to be natural, healthier, and achieve wellness (Koven & Abry, 2015), but in other cases, the individuals have religious or spiritual aspirations and wish to reach purity or perfection through diet (Varga et al., 2013). These individuals’ eating habits make them feel in control, proud, and even superior to other people. When they transgress their self-imposed rules, they feel guilty and punish themselves (Varga et al., 2013). Thus, ON symptoms are ego-syntonic: The eating habits and ideas becomes a central in patients’ lives, giving them a sense of identity (Varga et al., 2013).

Professionals from the field of eating disorders recognize this behavioral pattern in their practice (Vandereycken, 2011) and there are descriptions of some clinical cases resembling the definition of ON (Catalina, Bote, García, & Ríos, 2005; Moroze et al., 2015). However, ON is still a controversial construct and there is no consensus about whether it has sufficient entity to be considered an independent disorder or whether should be categorized as a subtype of an existing mental disorder, such as eating disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, hypochondriasis, or even a psychotic disorder (Brytek-Matera, 2012; Catalina et al., 2005; Varga et al., 2013).

To progress in the conceptualization of ON, the first step requires having valid and reliable instruments. The first questionnaire created specifically to measure ON was Bratman’s Ortorexia Test (Bratman & Knight, 2000). It is a 10-item questionnaire rated on a dichotomous scale (yes/no) which was created as screening tool for early diagnosis of ON. Scores of four and five affirmative answers indicate some level of ON. To our knowledge, there are no data about the internal structure or reliability of this instrument.

Based on Bratman’s Test, Donini, Marsili, Graziani, Imbriale, and Cannella (2005) developed the ORTO-15. This questionnaire is composed of 15 items rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from always to never. Lower scores are indicative of ON. The ORTO-15 is the most popular questionnaire used to evaluate ON. It has been translated and validated in various languages such as Turkish (Arusoğlu, Kabakçi, Köksal, & Merdol, 2008), Portuguese (Alvarenga et al., 2012), Hungarian (Varga, Konkolÿ Thege, Dukay-Szabó, Túry, & van Furth, 2014), Polish (Brytek-Matera, Krupa, Poggiogalle, & Donini, 2014; Stochel et al., 2015), German (Missbach et al., 2015), and Spanish (Roncero et al., 2017).

Despite the popularity of this questionnaire, it presents some important limitations. Missbach et al. (2015) concluded that the German version of the ORTO-15 “is only a mediocre tool for assessing orthorectic tendencies” (p. 1), and Roncero et al. (2017) concluded that “the ORTO, used in most of the studies as if it were considered the gold-standard, is not very golden” (p. 8). The problems with the ORTO-15 involve almost any aspect of its psychometric characteristics: Instability in its internal structure across several samples (see Roncero et al., 2017, for a review), low internal consistency (Alvarenga et al., 2012; Arusoğlu et al., 2008; Brytek-Matera et al., 2014; Missbach et al., 2015; Roncero et al., 2017), doubts about the scoring scheme of the questionnaire (Roncero et al., 2017), doubts about the score interpretation (Alvarenga et al., 2012; Herranz, Acuña, Romero, & Visioli, 2014; Souza & Rodrigues, 2014; Varga et al., 2014), and limitations in content validity (Roncero et al., 2017).

The Eating Habits Questionnaire (EHQ; Gleaves, Graham, & Ambwani, 2013) was recently developed. This is a 21-item questionnaire created to measure cognitions, behaviors, and feelings related to healthy eating. It consists of three subscales with satisfactory internal consistency (alphas in the range of (.72, .90)) and test-retest reliability (r in the range of (.72, .81)): (1) Knowledge of Healthy Eating, (2) Problems Associated with Healthy Eating, and (3) Feeling Positively about Healthy Eating. According to the authors, it can be used to identify cases in which individuals have problematic preoccupations with healthy eating. However, the EHQ does not consider negative emotionality (i.e., anxiety, fear, sadness, and distress) that may be associated with the overwhelming and distressing concern about eating contaminated or unhealthy foods (Catalina et al., 2005), or compulsive behavior (Koven & Abry, 2015). Moreover, the items do not reflect self-punishment when the person does not follow the imposed rules. In sum, the EHQ does not include items representing the distressing extreme of preoccupation with healthy eating.

In sum, to our knowledge, there is no available instrument evaluating every aspect of orthorexia or ON with sufficient psychometric guarantees (Missbach, Dunn, & König, 2017). Consequently, the objective of the present study was two-fold. First, to develop and validate a new questionnaire (in Spanish) of orthorexia and, second, to analyze the association with other psychological constructs and disorders theoretically related to orthorexia: eating disorder symptoms, obsessive-compulsive disorder symptoms, negative affect, and perfectionism. Given the content of orthorexia and previous literature (limited in its interpretability, as it not clear if the current intruments assessing ON are really measuring it), we expected the ON would have positive associations with the different disorders.

Development of the Teruel Orthorexia Scale

A review of the literature about ON was performed and each key element of was extracted from the different articles. A table of specifications with all these elements was developed and all the authors agreed with it. Both authors of the present manuscript had reviewed the previous literature about ON, participated in the adaptation of the ORTO-15 to Spanish, and published papers about eating styles and eating disorders, so both can be considered with enough expertise for defining construct content. Given that almost all the literature about orthorexia has been focused on ON, the content of the non-problematic approach to “right appetite” was less clear.

The two authors and a colleague independently developed a battery of approximately 30 items related to the construct of ON that guaranteed that all the aspects of the table were covered. Then, a total of 93 items were examined. Literaly or almost literaly repeated items were eliminated, leading to a list of 46 items. After wording inspection, some of the items were reformulated. Then, each author independently grouped the items depending on their content. The content domain was defined by reviewing the literature about ON. The independent classifications were compared and the possible lack of any aspect of ON was evaluated. Subsequently, the number of items for each category was balanced. Some items were removed to avoid excess of redundancy, to avoid too many items about specific content areas. Our goal was to produce a test with mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive content. A final 31-item version was obtained. The item wordings are shown in Table 1. The Spanish version can be found in Appendix 1 .

Method

Participants and Procedure

Data were collected through the Internet. The authors distributed the link to the survey through the e-mail distribution lists of the students of the Universidad de Zaragoza (Spain). Participants provided informed consent after reading the description of the study, where the anonymity or confidentiality of the responses was clearly stated. Participants had to be 18 years old or older to take the survey. Participants could provide an e-mail address so we could contact them for a retest. All the items had to be responsed in the survey (except e-mail address), so we had no missing values.

A total of 942 participants completed the measures in the first wave: 716 were women (76.0%) and 226 men (24.0%). Mean age was 24.01 years (SD = 6.40, range of (18. 66)). Regarding educational level, 0.3% of the sample reported not having any studies or only primary studies, 2.4% had secondary studies, 72.4% were university students, and 24.8% had completed university studies. We collected responses for the retest 18 months after the initial wave. The sample size for the retest was equal to 148.

Instruments

We describe the questions and questionnaires for the initial wage. In the retest, only the TOS had to be completed.

Sociodemographics. Participants provided information about their sex, age, education level, weight (to the nearest kilogram) and height (to the nearest centimeter).

Teruel Orthorexia Scale (TOS). This is the self-report questionnaire under study. The initial version consists of 31 items with a 4-point Likert scale from ranging from 0 = Completely disagree to 3 = Completely agree.

ORTO-15 (Donini et al., 2005). This self-report questionnaire measures severity of ON. It consists of 15 items (e.g., "In the last 3 months, did the thought of food worry you?") rated on a 4-Likert scale ranging from 1 = Always to 4 = Never. Low total scores are indicative of ON and high scores of normal eating behavior. For the present study, the Spanish validation of Roncero et al. (2017) was used. We used the scoring scheme proposed by Donini et al. (2005) and all the 15 items (not any of the reduced versions). In accordance with the described limitations of the instrument, Cronbach’s alpha in the present sample was .21. Although this is a very low value, we decided to keep this instrument in our study as the ORTO-15 has been the 'de facto' gold standard in the assessment of orthorexia (Roncero et al., 2017). From our point of view, the ORTO-15 should be abandoned and we only included it for completeness.

Obsessive Compulsive Inventory-Revised (OCI-R; Foa et al., 2002). The OCI-R is a self-report questionnaire that assesses distress caused by obsessive-compulsive symptoms. The OCI-R contains 18-items (e.g., "I find it difficult to control my own thoughts") rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 = Not at all to 4 = Extremely. Cronbach’s alpha in the present sample was .88. We used the Spanish version validated by Fullana et al. (2005).

Eating Attitudes Test-26 (EAT-26; Garner, Olmsted, Bohr & Garfinkel, 1982). The EAT-26 is a self-report that assesses attitudes and behaviors related to eating disorders, mainly anorexia nervosa. It consists of 26 items responded on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = never to 6 = always, grouped on three subscales: Dieting (13 items; e.g., "I am terrified about being overweight"), Bulimia and Food Preoccupation (6 items; e.g., "I find myself preoccupied with food"), and Oral Control (7 items; e.g., "I avoid eating when I am hungry"). Cronbach’s alphas in the present sample were .91, .68, and .70, respectively. For the present study, the Spanish version of Castro, Toro, Salamero and Guimerá (1991) was used.

Negative Affect Scale of the Positive and Negative Affect Scales (PANAS,Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1998). The negative affect dimension of the PANAS (N-PANAS) is a self-report questionnaire that assesses a general dimension of psychological distress. The N-PANAS is composed of 10 items (e.g., "Nervous") with a 5-point response scale ranging from 1 = Not at all to 5 = Extremely. Cronbach’s alpha in the present sample was .88. The Spanish adaptation of Sandín et al. (1999) was used.

Appearance Evaluation Scale of the Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire-Appearance Scales (MBSRQ;Cash, 2000). This scale assesses the degree of satisfaction with one’s own body. It is composed of seven items (e.g., "I like the way my clothes fit me ") with a 5-point response scale ranging from 1 = Definitely disagree to 5 = Definitely agree. Cronbach’s alpha in the present sample was .90. We used the Spanish adaptation (Roncero, Perpiñà, Marco, & Sánchez-Reales, 2015).

Concern over Mistakes Scale of the Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (FMPS;Frost, Marten, Lahart, & Rosenblate, 1990). This scale assesses the tendency to experiment negative emotions because of a minimal mistake, interpreted as a failure. It is composed of nine items (e.g., "The fewer mistakes I make, the more people will like me") with a 5-point response scale ranging from 1 = Strongly disagree to 5 = Strongly agree. Cronbach’s alpha in the present sample was .91. The Spanish adaptation was used (Gelabert et al., 2011).

Data Analysis

First, we analyzed the internal structure of the TOS scores with exploratory factor analysis (EFA). In order to determine the numbers of dimensions to be retained -which could not be anticipated before data analysis-, we used parallel analysis (Garrido, Abad, & Ponsoda, 2013), visual inspection of the scree-plot, and we considered theoretical interpretability of the solutions, factor simplicity, and loading sizes. We used the initial item pool of 31 items to develop a final and reduced item-pool, with a clear factor structure and high loadings, to achieve high reliability with a short measure. For this purpose, only items with loadings over |.51| were retained and no cross-loading greater than |.30|.

As we used a 4-point Likert scale, models were analyzed using robust weighted least squares (WLSMV estimator in MPlus). According to conventional cut-offs (e.g., Hu & Bentler, 1999), values greater than .90 and .95 for the comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) are considered to be indicative of an adequate and excellent fit to the data, respectively, whereas values smaller than .08 or .06 for the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) support acceptable and excellent model fit, respectively. It should be noted that those cut-offs were developed for confirmatory factor analysis with continous responses, so those values should be considered with caution. The authors are not aware that specific cut-offs have been proposed for EFAs with categorical variables.

Reliabilities were estimated with Cronbach’s alpha and test-retest correlations. We computed Pearson correlations between the different dimensions of the TOS scores and the other measures. If the TOS turned out to be a multidimensional instrument, we would compute partial correlations between the different factors of the TOS and the other variables, while controlling for the rest of the TOS factors. The following descriptives of the item scores were computed: mean, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis.

The analysis were performed with Mplus 7.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2015) and R 3.3.2 (R Core Team, 2016), with packages psych version 1.6.12 (Revelle, 2017) and MplusAutomation version 0.6-4 (Hallquist & Wiley, 2008).

Results

Internal Structure of the Teruel Orthorexia Scale

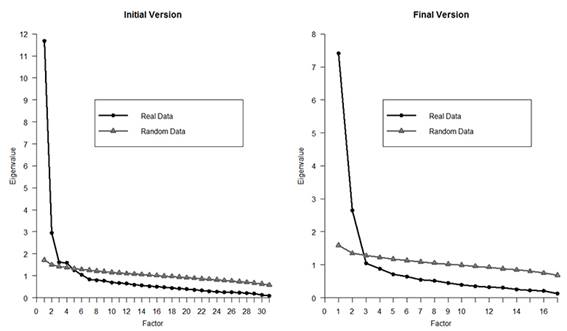

The results from the parallel analysis, which can be seen in Figure 1, with the initial version of the TOS were inconclusive. Four eigenvalues from the sample were greater than the eigenvalues from the randomly generated datasets, although the difference for the third and fourth eigenvalues was very small. The four-factor solution, although it provided an adequate fit to the data, χ2(347) = 1035.6, CFI = . 963, TLI = .950, RMSEA = .046, was not easily interpretable. With a loading threshold of |.51|, only three items loaded on the second factor and two items on the third, and several of them had important cross-loadings in the other factors.

Figure 1 Parallel analysis of the Teruel Orthorexia Scale responses with the initial version (31 items) and final version (17 items).

Following the scree-plot, we evaluated the two-factor solution. A slightly worse fit was found, χ2(404) = 1863.4, CFI = .921, TLI = .909, RMSEA = .062. The distribution of the loadings can be seen in Table 1. With a threshold of |.51|, several items did not present salient loading on either factor, but both factors were theoretically interpretable. These items were removed, leading to a version with 17 items.

With this shortened and refined version, the parallel analysis and the scree-plot clearly suggested the appropriateness of retaining two factors. The fit of this two-factor solution was satisfactory, χ2(103) = 453.9, CFI = .965, TLI = .954, RMSEA = .060. It was also theoretically meaningful. The first factor, where nine items presented salient loadings, was labeled Healthy Orthorexia, with items such as “I mainly eat foods that I consider to be healthy” or “I believe that the way I eat is healthier than that of most people”. The mean loading on this factor was .65, with a range of (.50, .86). This factor assessed interest in following what the participants considered a healthy diet. The second factor was labeled Orthorexia Nervosa, with items such as “Thoughts about healthy eating do not let me concentrate on other tasks” or “I feel overwhelmed or sad if I eat food that I consider unhealthy”, with a mean loading of .76, and range of (.63, .96). In this factor eight items presented relevant loadings. This second factor assessed the negative consequences of the concerns: interference caused by the concerns, negative emotions, and self-punishment. The secondary loadings were small, but non-negligible, maximum = .24. Both factors presented a medium-sized correlation, r = .43. The correlation between observed scores -not factors- was almost the same, r = .46.

Descriptives, Reliabilities, and Relation with Other Variables

The possible range of scores for Healthy Orthorexia was (0, 27). The mean score was 12.52, almost at the mid-point. For Orthorexia Nervosa, the acceptable range was (0, 24), and the mean was 3.57. This indicates that the majority of the participants presented very low scores on this dimension. These scores for Orthorexia Nervosa correspond with the low means and standard deviations of the items and high skewness and kurtosis. Items like "Thoughts about healthy eating do not let me concentrate on other tasks" are endorsed by very few participants (M = 0.1). (in Table 2)

Healthy Orthorexia reached a Cronbach’s alpha of .85 (.80 in the retest sample) and the alpha of Orthorexia Nervosa was .81 (.90 in the retest sample). We computed correlations between a dummy variable indicating whether the participants in the initial wage took part in the retest and the other variables. The correlations were very small, all |r| ≤ .10. We interpret this as an indication that the participants that took part in both waves are not different in the key variables to the participants that only responded in the first wage. After 18 months, the correlation among both scores of Healthy Orthorexia was .73; among both scores of Orthorexia Nervosa was .82.

Both factors of the TOS present a medium-sized correlation with the most commonly used measure of ON, the ORTO-15 (r = -.48 for Healthy Orthorexia and r = -.41 for Orthorexia Nervosa). The mean correlation between the orthorexia factors and the measures of psychological maladjustment (OCI-R, EAT scales, negative affect from the PANAS, physical self-esteem from the MBSRQ-reversed correlation sign-, and perfectionism from the FMPS) was much higher for the Orthorexia Nervosa scale (mean r = .42) than for the Healthy Orthorexia scale (mean r = .15). The highest correlations were found between Orthorexia Nervosa and the EAT-26 Diet and Bulimia scales (rs = .67). Both orthorexia scales presented small and statistically nonsignificant correlations with the body mass index (|rs| ≤ .06).

An interesting picture emerged when we computed partial correlations between the different measures and each of the two factors of the TOS while controlling for the other factor. For Healthy Orthorexia, whereas the mean Pearson correlation with measures of psychological distress was positive, the mean partial correlation was negative, r p = -.11. For instance, whereas Healthy Orthorexia and Diet presented a low-medium-sized Pearson correlation, r = .30, the partial correlation was -.01; whereas Healthy Orthorexia and perfectionism presented a very small positive correlation, r = .08, the sign of the association was reversed when controlling for the other factor of the TOS, r p = -.13. For Orthorexia Nervosa the mean correlation when controlling for the other factor was unchanged, with a mean partial correlation = .43. Whereas Healthy Orthorexia presented a negative and small partial correlation with body mass index (r p = -.08), a positive and small partial correlation was found with Orthorexia Nervosa (r p = .06). The scores of Orthorexia Nervosa were much more strongly related to psychological maladjustment than the scores of the ORTO-15.

Discussion

The present study had two main goals. The first was to develop and carry out an initial validation of a new instrument for assessing orthorexia. Previous instruments had important limitations in terms of reliability or internal structure (for instance, in the present sample the Cronbach's alpha of the ORTO-15 was equal to .21) and, also, content validity problems. For a long time, only the focus on the problematic approach to healthy eating has been considered. We expanded the conceptualization of orthorexia to include both problematic and non-problematic aspects of healthy eating. The second was to analyze the connections of orthorexia with several psychological constructs with which it is expected to be associated, using an instrument with better psychometric properties than the ORTO-15.

Starting with an initial item bank of 31 items, we proposed a bidimensional test of orthorexia. Thus, there is not a single continuum in the approach to healthy eating, ranging from no interest at all to problematic concern with it, passing to a middle point of healthy interest. The TOS, with 17 items, encompassed two related, although differentiable (r = .43), aspects of orthorexia. The first factor, Healthy Orthorexia, is assessed with nine items. The second factor, Orthorexia Nervosa, has eight items. The scores of both dimensions presented satisfactory reliabilities. Regarding the association with the assessed variables, results showed that, for a constant level of Orthorexia Nervosa, increments of Healthy Orthorexia were unrelated or negatively related to changes in several measures of psychological distress or psychopathology. With respect to Orthorexia Nervosa, it was positively related to psychological distress, restrained eating, obsessive-compulsive symptoms, perfectionism, and low physical self-esteem. This pattern of correlations was not altered when controlling for Healthy Orthorexia.

The structure of the instrument and its relations with additional variables of these two dimensions shed light on the interpretation of their theoretical meaning. Results show two differentiable dimensions in preoccupation about diet. On the one hand, Healthy Orthorexia evaluates the tendency to eat healthy food and interest in doing so. It represents a healthy interest with diet, which is independent of psychopathology (eating disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and negative affect), and even inversely associated with it. People with high scores on this factor are interested in a healthy diet, they spend a considerable amount of time and money buying, planning and preparing healthy food. This interest is in accordance with their self, as they describe their attitudes almost as a “way of life”. This factor represents the so-called “orthorexia (non-nervosa)”. On the other hand, Orthorexia Nervosa assesses the negative social and emotional impact of trying to achieve a rigid way of eating. This dimension represents a pathological preoccupation with a healthy diet, which corresponds with the so-called “orthorexia nervosa”. People scoring high on this factor are highly concerned with and overwhelmed by their preoccupations, which lead them to negative consequences such as self-punishment, social isolation, and guilt. This factor is associated with obsessive-compulsive symptoms, but mainly with eating symptoms, in accordance with previous studies that suggest an association between eating disorders and ON (e.g., Bundros, Clifford, Silliman, & Neyman Morris, 2016). This recovered pattern of assocations offer further evidence about the validity of the new scale.

Until the present, the literature has not been very clear about whether ON is an eating disorder, a variant of a currently recognized eating disorder, or a separate disorder. Mac Evilly (2001) suggested that ON was more aptly considered a risk factor for developing a future eating disorder (over time, orthorexia may lead to an eating disorder, as the diet becomes more refined and compulsive), rather than an eating disorder itself. Cartwright (2004) indicated that ON might precede anorexia nervosa or result from it. The association between ON and eating disorders should be further studied to determine whether the nature of this relationship is due to artifacts, given the association between some items of EAT related to food awareness and the ON (Rogoza, Brytek-Matera, & Garner, 2016), or whether there is a subjacent communality or vulnerability that explains the relationship. We consider that the medium-high correlation between Orthorexia Nervosa and the EAT-26 scores indicate that all these constructs imply a restrained eating style: While ON is focused in what to eat, previous approaches to eating restriction have stressed how much to eat.

This study offers useful information about the assessment of orthorexia and its connection with relevant psychological constructs. Given the important limitations of the ORTO-15 (Donini et al., 2005), which has been the most commonly used instrument for assessing ON, the TOS can be useful in this area. It broadens the conceptualization of orthorexia with differentiable dimensions: It is possible to distinguish between orthorexia and orthorexia nervosa. Although it is a short measure, its internal consistencies are over .80. Considering the time lapse among the test and the retest, correlations over .70 can be considered as very high.

Despite this, we note several limitations. First, the sample is mainly composed of university students and with a majority of women. Second, all our measures are self-reported. Moreover, the lack of a consensual definition of ON limits the analysis of the content validity of the new instrument. To address this possible limitation, we conducted a careful review of the literature.

This study presents a promising new instrument that offers possibilities in the study of ON. Further studies should analyze the psychometric properties of the TOS in other specific samples. Further cross-validations of the instrument should be done in order to test the stability of the results in community and clinical samples. The relation between orthorexia and other well studied eating styles like external eating, emotional eating, and restrained eating (e.g., Barrada, van Strien, & Cebolla, 2016) should be evaluated. The use of the TOS will help in the necessary task of better defining the construct of orthorexia and its relationship with other disorders and psychological dimensions.