Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Gaceta Sanitaria

versión impresa ISSN 0213-9111

Gac Sanit vol.25 no.3 Barcelona jun. 2011

Experiences about HIV-AIDS preventive-control activities. Discourses from non-governmental organizations professionals and users

Experiencias sobre la prevención y el control del VIH-sida. Discursos de los profesionales y usuarios de las organizaciones no gubernamentales

Anna Berengueraa,b, Enriqueta Pujol-Riberaa, Concepció Violana, Amparo Romaguerac, Rosa Mansillad, Albert Giménezd y Jesús Almedac,e

aResearch Department, Primary Health Care Research Institute (IDIAP- Jordi Gol), Catalan Health Institute (ICS), Barcelona, Spain

bHealth Department, Medicine Faculty, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

cPrimary Health Department Costa de Ponent, Catalan Health Institute (ICS), IDIAP-Jordi Gol, Gerència Territorial Metropolitana Sud, L'Hospitalet del Llobregat, Barcelona, Spain

dAIDS Programme. Public Health Department. Ministry of Health. Government of Catalonia, Spain

eCIBER, Epidemiology and Public Health (CIBERESP), Spain

This study has been funded by the AIDS Programme, Public Health Department of the Ministry of Health, Government of Catalonia.

ABSTRACT

Objectives: The main aim of this study was to identify the experiences of professionals in nongovernmental organizations (NGO) in Catalonia (Spain) working in HIV/AIDS prevention and control activities and potential areas of improvement of these activities and their evaluation. A further aim was to characterize the experiences, knowledge and practices of users of these organizations with regard to HIV infection and its prevention.

Methods: A phenomenological qualitative study was conducted with the participation of both professionals and users of Catalan nongovernmental organizations (NGO) working in HIV/AIDS. Theoretical sampling (professional) and opportunistic sampling (users) were performed. To collect information, the following techniques were used: four focus groups and one triangular group (professionals), 22 semi-structured interviews, and two observations (users). A thematic interpretive content analysis was conducted by three analysts.

Results: The professionals of nongovernmental organizations working in HIV/AIDS adopted a holistic approach in their activities, maintained confidentiality, had cultural and professional competence and followed the principles of equality and empathy. The users of these organizations had knowledge of HIV/AIDS and understood the risk of infection. However, a gap was found between knowledge, attitudes and behavior.

Conclusions: NGO offer distinct activities adapted to users' needs. Professionals emphasize the need for support and improvement of planning and implementation of current assessment. The preventive activities of these HIV/AIDS organizations are based on a participatory health education model adjusted to people's needs and focused on empowerment.

Key words: Organizations. HIV. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Qualitative research. Focus Groups. Interviews as topic. Health education. Program evaluation.

RESUMEN

Objetivos: Identificar las experiencias y actividades de las organizaciones no gubernamentales (ONG) que trabajan en la prevención y control del VIH/sida, las posibles áreas de mejora de las actividades y de su evaluación, e identificar las experiencias, conocimientos y prácticas de sus usuarios sobre el VIH y su prevención.

Métodos: Estudio cualitativo fenomenológico en el que participan los profesionales y usuarios de las ONG que trabajan en VIH. Se realizó un muestreo teórico (profesionales) y un muestreo opinático (usuarios). Se utilizaron cuatro grupos focales y uno triangular (profesionales), 22 entrevistas semi-estructuradas y dos observaciones (usuarios). Se realizó un análisis de contenido temático realizado por tres analistas.

Resultados: Los profesionales de las ONG ofrecen un enfoque holístico, confidencialidad, competencia cultural y profesional, y aplican los principios de igualdad y empatía. Los usuarios tienen conocimientos sobre el VIH/sida y comprenden el riesgo de infección. Existe una separación entre conocimiento, actitud y conducta.

Conclusiones: Las ONG ofrecen diversas actividades adaptadas a las necesidades de los usuarios. Los profesionales destacan la necesidad de apoyo y mejora de la planificación y ejecución del proceso de evaluación actual. Las actividades preventivas de las ONG que trabajan en VIH/sida se basan en un modelo de educación sanitaria participativa ajustado a las necesidades de la población, basada en el empoderamiento.

Palabras clave: Organizaciones. serodiagnóstico del sida. Sida. Investigación cualitativa. Grupos focales. Entrevistas como asunto. Educación en salud. Evaluación de programas y proyectos de salud.

Introduction

A number of HIV-related nongovernmental organizations (NGO) work to promote prevention and health (AIDS-NGO) and provide care and help to persons with HIV. The role of these organizations has been critical in the fight against HIV since the onset of the epidemic1.

In many countries, AIDS-NGO have led the initiative against HIV. These organizations are the largest providers of preventive activities against HIV-AIDS, particularly among groups showing high-risk behavior: commercial sex workers, injecting drug users, men who have sex with men, youths in high-risk situations, persons living with HIV/AIDS, prisoners and immigrants2,3. The activities of AIDS-NGO are complementary to those in the public health sector and these entities act as a bridge or as "communicative spaces" between marginalized communities or immigrants and health services4-7.

Since the start of the of the AIDS Prevention and Care Program in Catalonia (Spain), the importance of promoting and coordinating the activities of the various NGO in the field of HIV/AIDS has been highlighted8 and the preventive, health promotion and care activities of AIDS-NGO have increased3,8,9.

The core activities of AIDS-NGO are as follows: providing HIV prevention peer education; distributing educational materials; promoting health education and safe sex activities; participating in commemorative AIDS acts, providing counselling and rapid testing of HIV and syphilis; receiving health services and referrals, when necessary; promoting adherence to antiretroviral treatments; conducting emotional support sessions and individual psychological therapies; and providing legal advice and advocacy10,11. These organizations have interdisciplinary teams, usually consisting of psychologists, physicians, social workers, social educators, nurses, experts and volunteers.

Information on the preventive activities of AIDS-NGO is only available in the technical or yearly reports of these organizations3,8. Few studies have been published on the experiences and opinions of AIDS-NGO to fully understand their preventive programs and their needs and challenges3 or to describe the dearth of financial and human resources of NGO12. The present study reports the experiences and practices of AIDS-NGO to describe how these organizations work and how their activities are perceived by users.

This study is part of a major study aiming to identify a set of valid and reliable indicators to facilitate assessment of the activities carried out by AIDS-NGO. The main objective of this study was to identify the experiences of professionals in Catalan NGO working in HIV/AIDS preventive and control, the potential areas for improvement of these activities, and their evaluation. A further aim was to identify the experiences, knowledge and practices of users of these programs related to HIV infection and its prevention.

Methods

We carried out a qualitative study using a phenomenological approach to identify and interpret discourses (professionals and users) on individual experiences in the social world expressed through language13.

Sampling

Professionals and users from 36 out of the 40 AIDS-NGO funded by the Department of Health agreed to take part in this study. For the professionals, a theoretical sampling based on prior definition of participants' characteristics was carried out to obtain optimal variety and discursive wealth to reach data saturation. The variables used to define the informant profile of AIDS-NGO professionals were as follows: AIDS-NGO target population (commercial sex workers, injecting drug users, men who have sex with men, youth in high-risk situations, persons living with HIV/AIDS, prisoners and immigrants), age, sex, professional profile, setting (urban or rural) and years of experience.

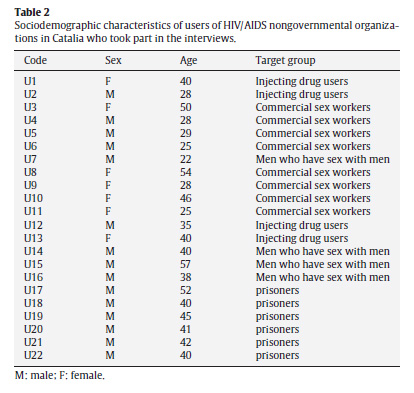

Due to the difficulties of theoretical sampling, opportunistic sampling was finally performed for the AIDS-NGO users. However, heterogeneity criteria were taken into account. The variables used to define the users were AIDS-NGO target population, age, sex, nationality, serostatus, and length of relationship with the organizations.

Tables 1 and 2 describe informants' sociodemographic characteristics.

Professionals were recruited by the research team through informative telephone calls requesting participation.

To identify users, key informants of AIDS-NGO were ask to provide information about the study and to request participation via news boards and web pages. The group of youths at high-risk was selected according to their availability in terms of time and location.

Techniques to generate information

Distinct techniques were used14. For professionals, focus groups15 and triangular groups were employed16. In the focus groups, the instrument used to stimulate individual speech was interaction15. For users, semi-structured interviews were employed because sensitive issues may arise17 during their the course of the interview. Open, focused and non-systematic observation of theater performances in teenagers and young adults was also employed18.

The use of the different techniques was justified by the feasibility and accessibility of the informants and the triangulation of information collecting techniques19,20.

Four focus groups and one triangular group took place among the AIDS-NGO professionals. Twenty-two semi-structured interviews for users were completed, as well as two observations of youth and teenager groups. For the group interviews, professionals were segmented according to their target group. The number of personal interviews was determined by examining the discursive representativity of users' high-risk activities and data saturation.

Forty-two professionals from 36 AIDS-NGO were invited to participate in the focus groups and 36 participated. Six professionals could not attend due to incompatibility with their work schedules.

Setting and data collection

Data collection was performed between February and June 2008. Focus groups were held in a neutral place (Jordi Gol Institute of Research in Primary Care) and included a moderator and an observer. The semi-structured interviews took place in the users' work place or at the AIDS-NGO venues. The observations were made in two secondary schools.

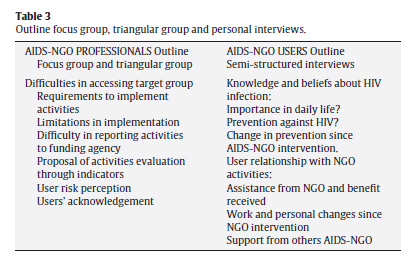

To explore the various topics, an outline was used in the development of the focus groups, the triangular group and users' interviews (Table 3). During these techniques, field notes were taken. Group interviews lasted for 90-120 minutes, semi-structured interviews for 30 minutes and observations for 60 minutes. In the group and individual interviews, data saturation was reached3,19,21,22. All the informants verified the information.

Ethical aspects

This study was conducted according to the Helsinki Declaration and Good Clinical Research Practice. Participants signed informed consent forms at the beginning of each focus group or interview. The confidentiality and anonymity of the data was ensured through a code given to each informant23. This code was used to identify the selected verbatim-transcripts. The transcripts were anonymous and made by trained external personnel. The project was approved by the Ethical and Clinical Research Committee of the Jordi Gol Institute of Research in Primary Care.

Data analysis

The analysis was based on notes from the observations and from the literal and systematic transcriptions of the data24. A thematic interpretive content analysis was carried out with the support of Atlas.ti and Nvivo software. Three researchers independently analyzed the data. The results were subsequently discussed and a consensus was reached14,19,25.

The analysis took place as follows: a) careful reading of all the transcripts, b) identification of the relevant subjects and texts, c) fragmentation of the text in units of meaning, d) text codification with a mixed strategy through emerging codes and predefined codes, e) creation of categories by grouping the codes by the criterion of analogy, according to pre-established analytical criteria in the objectives of the study and new elements from the comments, f) identification of emerging categories not initially planned, g) analysis of the points of agreement and disagreement, h) triangulation of the results26.

Results

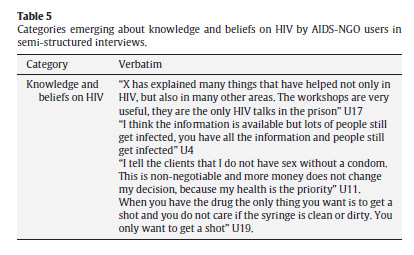

The results are structured according the comparison between professionals' and users' discourses. Verbatim records of informants' discourse are shown in Tables 4 and 5. The quotations were translated from Catalan, Spanish and Portuguese to English.

Characteristics of HIV-AIDS prevention and control activities: professionals' and users' experiences

1) Holistic approach

AIDS-NGO professionals reported that they offer services that target the whole person rather than focusing on preventing HIV infection. The professionals attend to users' basic needs before tackling HIV/AIDS-related issues. AIDS-NGO users agreed with professionals but some differences in the use of AIDS-NGO services were observed: the autochthonous population mainly required activities related to HIV prevention, while immigrants initially required social, legal and work-related services.

2) Cultural competence

AIDS-NGO currently provide care for a multicultural population with highly diverse needs. Cultural competence is defined as a set of congruent behaviors, attitudes, and policies that come together in an organization to enable it to work effectively in cross-cultural situations.

The professionals also underlined an important change in the approach to users. In the 1980s, talking about sexual relationships or condoms was still taboo, whereas currently the main problem is communication, language barriers, and knowing the degree of information assumed, due to cultural differences.

3) Confidentiality

Confidentiality pervades every AIDS-NGO activity. Professionals apply strategies to bring the organization and its users closer and create a bond.

4) Creation of horizontal relations between AIDS-NGO users and professionals

Professionals working with men who have sex with men, injecting drug users, or persons living with HIV/AIDS considered that the creation of horizontal relations based on equality and empathy was essential. Such relations were believed to facilitate accessibility and bonding between the professional and user and contribute to eliminating prejudices that are often held by health professionals. Users highlighted the perception of accessibility and availability and felt accompanied, emphasizing the human component of these interactions

5) Interdisciplinary approach

NGOs have professionals from distinct disciplines, which facilitates an interdisciplinary approach when addressing users' overall and specific needs. Some users reported that the AIDS-NGO had several, well-defined roles and provided assistance appropriate in each case. For instance, when diagnosis of HIV was made, the need to meet some other seropositive people and to receive psychological support was perceived as essential.

6) Evaluation of the objectives and activities of AIDS-NGO

In most group meetings, concerns about the difficulties of evaluating the work of AIDS-NGO were voiced. Some activities required a strong effort and dedication and quantitative indicators, such as the number of cases, were insufficient to evaluate them.

To improve assessment of the activities and objectives of AIDS-NGO, professionals suggested looking for quantitative and qualitative indicators that would provide a reliable measure of the process and its results.

7) Challenges and opportunities for improvement

Professionals reported that multiple activities required high mobility, the ability to adapt, creativity, imagination and innovation. The enquiries and requests for information received through the internet and e-mail from youths in high-risk situations and men who have sex with men were highly regarded. Therefore, these new technologies should be strengthened. Youths in high-risk situations reported that it was essential to be able to communicate their sexual concerns through the internet or via e-mail. Boys found it easier to consult via the internet and chose AIDS-NGO offering online services.

Another challenge was the need to reach invisible groups such as older men who have sex with men and commercial sex workers, the latter linked to illegal organizations and tending to work on the roadside where opportunities to assist them are very limited.

A major challenge for professionals was integrating users into the community, particularly in the case of injecting drug users. The informants explained that it is important to decrease drug consumption, to promote social integration, lower self-exclusion and aim at more controlled abuse.

Some users point out major challenges to improving AIDS-NGO services. These users stated that these organizations have limited resources available and cannot offer help in extreme situations. For them, AIDS-NGO need more funding or to join efforts with other related NGO to be able to offer more services. In addition, these users report that the locations of AIDS-NGO are unevenly distributed, with a need to reach the population outside the Barcelona area.

8) Acknowledgment of the AIDS-NGO

NGO professionals complained that other health and social providers did not sufficiently acknowledge their work. In reports, these professionals were required to continuously justify what they do and the result had an impact on funding.

Importantly, professionals' felt valued by the users who requested their help and recommended them to other users. They felt satisfied with their work and pointed out that AIDS-NGO promoted participation and self-healing.

9) Knowledge and beliefs on HIV infection among AIDS-NGO users

Adult users reported having good knowledge of HIV-AIDS infection, transmission and prevention and recognized the contribution of AIDS-NGO to their knowledge.

However, there were still contradictions among individuals. Despite being aware of the information, some people believed that infection does not occur in unprotected sex. Commercial sex workers often need strategies to convince people in their social context to use condoms. Moreover, an ex-injecting drug user explained that when you are addicted to drugs it is difficult to think about prevention. Youths in high-risk situations explained that condoms are often not used due to unplanned opportunities to have sex. At the same time, drug or alcohol abuse increase vulnerability and affect cognitive and emotional ability, which can influence the use of preventive measures.

Discussion

This qualitative study improves knowledge of the activities, attitudes and practices of AIDS-NGO professionals and users. NGO professionals working in HIV/AIDS adopt a holistic approach in their activities, maintain confidentiality, have cultural and professional competence and follow the principles of equality and empathy. Users have HIV/AIDS knowledge and understand the risk of infection and feel satisfied with the AIDS-NGO services.

These results agree with those obtained by Convisier and Pounds28, which emphasize the importance of offering ancillary services to people in need of HIV/AIDS prevention or treatment. Estrada et al29 show that a holistic person-based approach is essential to achieve a change in behaviour.

The preventive activities of AIDS-NGOs are based on a participatory health education model adjusted to people's needs. This model focusses on empowerment and knowledge and skills. This educational strategy follows the principles put forward by the World Health Organization27, highlighting the impact of person-based care in health improvement, quality of life, user trust and treatment adherence. In this educational model, professionals take into account the users' values and perspectives and incorporate them in the decision-making process30.

Users are satisfied with the AIDS-NGO activities because of empathic relationships, person-based care and the various activities organized. However, some feel that more resources and services are required to cover their demands.

The results confirm that AIDS-NGO target most of their activities at groups at risk of social exclusion or groups of socially vulnerable individuals to reduce social inequalities due to socioeconomic position, gender and social orientation. Our results also confirm the role of AIDS-NGO as a bridge and "space and communication" for health services and the population6 as well as with other services (legal, social, legal, employment, etc.). This evidence is consistent with the applicability of specific programs that require a community approach to adjust them to match the needs of the target population28,31.

The increase in the immigrant population, which is more socially vulnerable and shows high cultural diversity, requires the incorporation of other professionals, such as mediators4,32,33. A greater degree of creativity and cultural competence is required to design workshops with contents adapted to the distinct audiences, translation of informative materials and the creation of materials adapted to immigrants' linguistic and cultural needs. The importance of these roles justifies the inclusion of these professionals in the AIDS-NGO team, although their presence or availability in these teams varies.

The professionals regarded confidentiality as essential. The emerging virtual forums or web pages, as platforms to prevent and provide information on HIV-AIDS, contribute to inter-user support and to improving bonding with AIDS-NGO while preserving personal anonymity34,35. Internet-based HIV-AIDS preventive interventions have been shown to be as effective as personal-based interventions36. In our study, on-line consultations and web pages were more frequently used by young people. However, a recent study by Bull et al. shows that internet-based interventions need to be more intensive to maintain young people's attention over several sessions in order to be more effective37.

Despite the several strategies and activities performed by AIDS-NGO, there are still beliefs that hamper HIV-AIDS prevention: a) the time gap between a risky sexual encounter and the onset of the disease; b) unprotected sex facilitates closeness and intimacy with the partner and is perceived as a risk-free practice; c) risk perception is still based on the partner's external appearance, which implies unprotected sex with people "that look healthy"29,38. The triangulation of techniques in this study highlights the gap between knowledge and behavior with regard to HIV prevention. While more information is available than previously, this increase has not been followed by changes in risk behavior, particularly in the autochthonous population.

During the two observations, not all topics included in the focus groups and interviews were included and therefore data saturation in this population sector was not achieved. However, the results agree with those of other studies in the same group39. Caution is needed before extrapolating these results to other settings. However, the similarity with other studies suggests the applicability of our results.

Another limitation was that we did not study the views of other health providers working with HIV-AIDS prevention or control-programs (primary care, public health and reproductive and sexual health) due to practical impediments and lack of resources.Our study increases understanding of the role of AIDS-NGO. To date, few studies have analyzed the role of these organizations from the perspective of both professionals and users. Some studies in primary care have analyzed the point of view of professionals and patients40,41 but none refer to AIDS-NGO.

This study adhered to the following quality criteria of qualitative research14,19,25,42,43: (i) methods, data and analysis were triangulated; (ii) the analysis of triangulation established substantial agreement44; (iii) the participants had access to the summary of the transcripts to verify their contents.

In conclusion, AIDS-NGO offer distinct activities adapted to users' needs. Users are satisfied and feel comfortable with this education and health promotion model. This participatory model seems to be that which the user will subsequently use to facilitate HIV/AIDS prevention. When basic needs are solved, HIV-AIDS prevention activities become more effective. However, greater efforts seem to be required to create strategies that would close the gap between knowledge, attitudes and behavior. However, in the near future, more efforts should be made to improve services and cooperation between AIDS-NGO and other organizations or health services working in HIV/AIDS.

Authors' contribution

A Berenguera, E Pujol-Ribera, C Violan, A Romaguera, R. Mansilla, A Giménez and J Almeda, have been involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content and have given final approval of the version to be published. A Berenguera, E Pujol-Ribera, J Almeda, C Violan and A Romaguera have made substantial contributions to conception and design. A Berenguera and E Pujol-Ribera have been made the field work and the analysis and interpretation of data. Each author should have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the NGO professionals and users that have taken part in the study. We thank the IDIAP Jordi Gol for the funding of the translation of the manuscript into English.

We thank to Maria José Fernández de Sanmamed, Mariona Pons and Dolors Rodríguez for their substantial contributions in this manuscript.

References

1. UNAIDS. 2008 Report on the global AIDS epidemic. 2009. [ Links ]

2. Crane SF, Carswell JW. A review and assessment of non-governmental organization-based STD/AIDS education and prevention projects for marginalized groups. Health Educ Res. 1992; 7:175-94. [ Links ]

3. Kelly JA, Somlai AM, Benotsch EG, et al. Programmes, resources, and needs of HIV-prevention nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in Africa, Central/Eastern Europe and Central Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean. AIDS Care. 2006; 18:12-21. [ Links ]

4. Vulpiani P, Comellas JM, Dongen Van E. Health for all, all in health, Eureopean experiences on health care for migrants. Perugia: Cidis/Alisei; 2000. [ Links ]

5. Weizen EM, Weide MG. Accessibility and use of health services among ethnic minorities. A bibliography 1993-1998. Utrecht: Nivel Netherlands Institute of Primary Health Care; 1999. [ Links ]

6. de Souza R. Creating "communicative spaces": a case of NGO community organizing for HIV/AIDS prevention. Health Commun. 2009; 24:692-702. [ Links ]

7. Amirkhanian YA, Kelly JA, Benotsch EG, et al. HIV prevention nongovernmental organizations in Central and Eastern Europe: programs, resources and challenges. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2004; 12:12-8. [ Links ]

8. Departament de Salut. Memòria d'activitats de l'any 2008. Programa de Prevenció i Assistència a la SIDA. Barcelona: Departament de Salut Pública. Generalitat de Catalunya, 2008. [ Links ]

9. Sullivan PS, Hamouda O, Delpech V, et al. Reemergence of the HIV epidemic among men who have sex with men in North America, Western Europe, and Australia, 1996-2005. Ann Epidemiol. 2009; 19:423-31. [ Links ]

10. CDC 2009 Compendium of Evidence-Based Interventions http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/research/prs/evidence-based-interventions.htm. 2009. [ Links ]

11. Odindo MA, Mwanthi MA. Role of governmental and non-governmental organizations in mitigation of stigma and discrimination among HIV/AIDS persons in Kibera. Kenya. East Afr J Public Health. 2008; 5:1-5. [ Links ]

12. Akukwe C. The growing influence of non governmental organisations (NGOs) in international health: challenges and opportunities. J R Soc Health. 1998; 118:107-15. [ Links ]

13. Reeves S, Albert M, Kuper A, et al. Why use theories in qualitative research?. BMJ. 2008; 337:a949. [ Links ]

14. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007; 19:349-57. [ Links ]

15. Krueger R, Casey MA, Focus Group. A practical guide for applied research. London: Sage Publications; 2000. [ Links ]

16. Conde F. Los grupos triangulares como espacios transicionales para la producción discursiva. La vivienda en Huelva. Culturas e identidades urbanas. Sevilla: Junta de Andalucia-Fundación El Monte, 1996, p. 275-307. [ Links ]

17. Bryman A. Social research methods. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2008. [ Links ]

18. Gilbert N. Researching social life. 2nd ed. London: Sage Publications; 2001. [ Links ]

19. Cohen DJ, Crabtree BF. Evaluative criteria for qualitative research in health care: controversies and recommendations. Ann Fam Med. 2008; 6:331-9. [ Links ]

20. Lambert SD, Loiselle CG. Combining individual interviews and focus groups to enhance data richness. J Adv Nurs. 2008; 62:228-37. [ Links ]

21. Fontanella BJ, Ricas J, Turato ER. Saturation sampling in qualitative health research: theoretical contributions. Cad Saude Publica. 2008; 24:17-27. [ Links ]

22. Tuckett AG. Qualitative research sampling: the very real complexities. Nurse Res. 2004; 12:47-61. [ Links ]

23. Tuckett AG. Part II. Rigour in qualitative research: complexities and solutions. Nurse Res. 2005; 13:29-42. [ Links ]

24. MacLean LM, Meyer M, Estable A. Improving accuracy of transcripts in qualitative research. Qual Health Res. 2004; 14:113-23. [ Links ]

25. Porter S. Validity, trustworthiness and rigour: reasserting realism in qualitative research. J Adv Nurs. 2007; 60:79-86. [ Links ]

26. Kalof L, Dan A, Dietz T. Essentials of social research. Glasgow: Open University Press; 2008. [ Links ]

27. World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2008 - Primary Health Care (Now More Than Ever). 2008. [ Links ]

28. Conviser R. Catalyzing system changes to make HIV care more accessible. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2007; 18(3 Suppl):224-43. [ Links ]

29. Estrada JH. Prevention models in the fight against HIV/AIDS. Acta Bioethica. 2006; 12:91-100. [ Links ]

30. Ruiz MR, Rodriguez JJ, Epstein R. What style of consultation with my patients should I adopt? Practical reflections on the doctor-patient relationship. Aten Primaria. 2003; 32:594-602. [ Links ]

31. Rhodes SD, Hergenrather KC, Wilkin A, et al. Preventing HIV infection among young immigrant Latino men: results from focus groups using community-based participatory research. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006; 98:564-73. [ Links ]

32. Rios E, Ferrer L, Casabona J, et al. Knowledge of HIV and sexually-transmitted diseases in Latin American and Maghrebi immigrants in Catalonia (Spain). Gac Sanit. 2009; 23:533-8. [ Links ]

33. Smacchia C, Di Perri G, Boschini A, et al. Immigration, HIV infection, and sexually transmitted diseases in Europe. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2000; 14:233-7. [ Links ]

34. Curioso WH, Kurth AE. Access, use and perceptions regarding Internet, cell phones and PDAs as a means for health promotion for people living with HIV in Peru. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2007; 7:24. [ Links ]

35. Ybarra ML, Bull SS. Current trends in Internet- and cell phone-based HIV prevention and intervention programs. Curr HIV /AIDS Rep. 2007; 4:201-7. [ Links ]

36. Noar SM, Black HG, Pierce LB. Efficacy of computer technology-based HIV prevention interventions: a meta-analysis. AIDS. 2009; 23:107-15. [ Links ]

37. Bull S, Pratte K, Whitesell N, et al. Effects of an Internet-based intervention for HIV prevention: the Youthnet trials. AIDS Behav. 2009; 13:474-87. [ Links ]

38. Bayes R. Sida y psicología. Barcelona: Martínez Roca; 1995. [ Links ]

39. Saura SS, Fernandez de Sanmamed Santos MA, Vicens VL, et al. Perception of the risk of adquire a sexually transmitted disease in a young population. Aten Primaria. 2010; 42:143-8. [ Links ]

40. Jimenez VJ, Cutillas CS, Martin ZA. Evaluation of results in primary are: the MPAR-5 project. Aten Primaria. 2000; 25:653-60. [ Links ]

41. Pujol RE, Gene BJ, Sans CM, et al. Primary health care product defined by health professionals and users. Gac Sanit. 2006; 20:209-19. [ Links ]

42. Mays N, Pope C. Qualitative research in health care. Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ. 2000; 320:50-2. [ Links ]

43. Walsh D, Downe S. Appraising the quality of qualitative research. Midwifery. 2006; 22:108-19. [ Links ]

44. Barbour RS. Checklists for improving rigour in qualitative research: a case of the tail wagging the dog?. BMJ. 2001; 322:1115-7. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

E-mail address: epujol@idiapjgol.org

(E. Pujol-Ribera)

Received 9 July 2010

Accepted 5 October 2010