Sexual behaviour, when not coerced, is widely recognized as more than simply a biological reproduction function, but mostly a leisure (Williams et al., 2020). Pursuing for pleasure in sexual activities, the mainly shared motive in Western populations (Wyverkens et al., 2018), conforms a common activity fulfilling human needs and increasing well-being (Berdychevsky & Carr, 2020; Diamond & Huebner, 2012; Satcher et al., 2015; Lehmiller et al., 2021; Xia et al., 2022).

Although traditionally addressed only by medical and health sciences (Williams et al., 2020), more recently, the positive effects on mental health of engaging in meaningful social leisure activities (Timonen et al., 2021) has led sexual behaviour to become the focus of multidisciplinary research, evolving the initial framework to a more complex and multidimensional one, including both leisure and health sciences (Williams et al., 2020).

In short, citing Williams et al. (2020, p. 9), “the integration of leisure and positive sexuality allows for a broad application of scholarship to diverse sexual issues (such as those related to identity, experiences, and preferences) across various structural levels that impact academics and professionals in medicine and healthcare, counselling and psychotherapy (…)”.

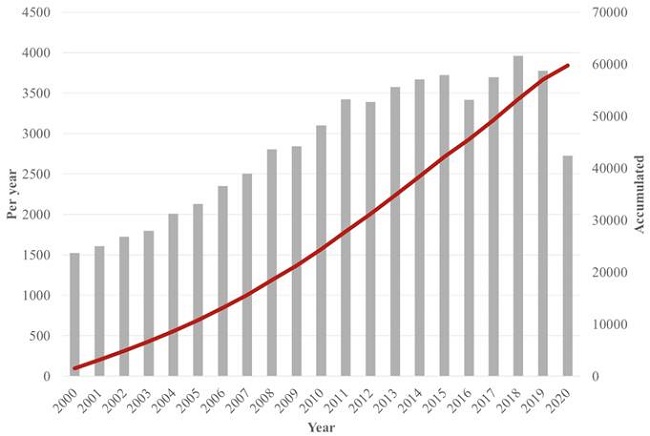

Volume of Research

Regarding this perspective, sexual behaviour is a broad and growing field of research. Just by looking up peer-reviewed articles containing “sexual behavior” in their title, abstract or keywords in PsycInfo database, limited to human subjects, without any other consideration such as “behaviour” (English or American writing) or any other related keyword like “sex experience” or “sexual attitudes”, 59760 documents were found, with an increasing trend for almost every year over the last two decades (Figure 1). It is also possible to find more signs of the interest in this field as, for instance, “sexual experience”, which is mentioned in 12044 reports in the same period. Indeed, it seems this area of study has been driving attention of many researchers.

Motor Behaviour

For a good understanding of what researching on sexual behaviour means, a clear distinction must be set: in behavioural science, researchers are used to deal with cognitive and emotional variables, not subjects of direct observations, in order to try to relate them with behaviours which, in other words, are visible actions. Thus, variables such as appeals and consequences foreseen, other people's opinions, and one's ability of execution are often used to predict those actions, patterns of actions or habits (Sheeran et al., 2016).

In fact, a general definition of behaviour, more specifically motor behaviour, is quite simple: it has been previously delineated as every kind of movement in every physical and social context (Adolph & Franchak, 2017). This includes every alternative of what subjects visibly do in the way they relate to the environment: “movements generate perceptual information, provide the means for acquiring knowledge about the world, and make social interactions possible” (Adolph & Franchak, 2017).

Thereby, the application of motor behaviour to sexual field must consider this “every movement” specifically oriented to erotic intercourse or sexual experience, taking here erotic and sexual as synonymous terms. Consequently, studying the repertoire of sexual actions, can be understood as a synonymous of mapping the compendium of those motor behaviours that are someway related to sexual experience.

Research on Repertoire

Is it possible to describe the human potential repertoire of sexual behaviour? Initially, the answer must regard the high plasticity of actions moderated by cognition and appeals (Sheeran et al., 2016), which can result in a huge number of possibilities. Nevertheless, research on the field has already explored it for decades attempting to select the best items, although, to our information, unfortunately, this task has been done in a not standardized way.

Along the XX century, there were published some reports trying to carry out a wide description of sexual repertoire, such as the famous attempt to explicitly research on sexual behaviours conducted by Kinsey on males (Kinsey et al., 1949), and on females (Kinsey et al., 1998), which, despite its severe methodological problems (Cornel, 2021), constituted one of the most acknowledged examples of sexual studies, even to the point of naming an Indiana University research institute (Kinsey Institute, 2022), and inspiring a popular film (Mutrux, 2004).

Other contemporary researchers attempted to pool human sexual repertoire (Cowart & Pollack, 2011, firstly published in 1988; Zuckerman, 1973). All of them presented different considerations from Kinsey et al. (1949) but, unfortunately, it is not possible to find any mention or explanation about the method for constructing, checking or revaluating their proposals, apart from their own narrative review of the bibliography, illustrating the lack of integration of perspective and method until that date.

Back in early 2000s, another far-reaching project was intended to draw a picture of sexual behaviour and dysfunction in populations beyond 40 years old (Laumann et al., 2005; Laumann et al., 2006; Nicolosi et al., 2004; Nicolosi et al., 2006). In this case, when trying to look for the design of the survey, despite the title of Global Study of Sexual Attitudes and Behaviours, the authors did not provide information about any gold standard of sexual repertoire, not even the criteria used to elaborate it.

The same issue is observed in Lindau et al. (2007) study on sexual dysfunction, which informed about the criteria for classification of sexual problems, but did not the same with sexual behaviour, where only some variables were mentioned, all in absence of specific referenced standard.

Another example is the research published by Wylie (2009) to “identify the variety of sexual behaviours undertaken by adults across the world” (p. 39), where he presented a pool of twelve options without explaining the method or criteria for consideration and inclusion. Although the list could be a sensible proposal, the author did not provide any explanation of what the rationale was to consider that classification sufficient to summarize every possible action, maybe assuming sexual intercourse can be composed of just 12 choices.

More recently, the Wesche et al. (2017) search for latent category profiles analysed the appearance of cluster classes and their links to emotional intention and consequences, again, without a certain explanation of their reasons to choose that specific list of behaviours.

Those are just some of the most cited and acknowledged studies focused on the search of wide classifications. However, when looking into sexual repertoire, the large-scale national surveys conducted in Finland (FINSEX) (Kontula, 2009, 2015), in USA NHSLS (Lauman et al., 2001) and NSSHB (Herbenick et al., 2010), in UK (NATSAL) (Erens et al., 2021), and in Australia (ASHR) (Smith et al., 2003) are probably the most extensive and comprehensive cases.

They all include a large number of variables apart from specific actions, and also draw a detailed frame of sexual behaviour, selecting specific variables for each applied study, which, consequently, changes the pool used in every case. Despite this huge effort, in terms of their baseline substantiation, we found that all those projects did not consider the same pack of motor behaviours. In fact, Herbenick et al. (2017) uphold that their National Surveys of Sexual Health and Behaviour (NSSHB) has more items than United Kingdom's National Surveys of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (NASTAL) (Erens et al., 2014; Erens et al., 2021) but less than Australian Survey of Health and Relationships (Richters et al., 2014). Eventually, as previous studies, they do not share the way they define actions and items, so some inconsistencies among them are found in the final sexual repertoire frame applied.

As we see, although sexual behaviour is a prolific field with a huge volume of studies, is still difficult to find consistent repertoires proposals under a common criterion in many studies, and it is possible to find reports not even mentioning any source (Hensel et al., 2008; Lehmiller et al., 2021; Shilo & Mor, 2020).

Aims

For all aforementioned, this work was intended to 1) propose a map of motor sexual behaviours which allows to exhaustively record any erotic situation given, and 2) test it through a systematic review of field research studies, which is also set as a method for further revision and expansion of the proposal, if needed.

Method

Map Structure

There is a primary clarification needed to be addressed in the map structure construction: taking into consideration, for instance, the label “anal sex”, it does not mention a real context behaviour. People perform or avoid anal sex in different contexts. Thus, other variables such as the number of people involved, the privacy of the venue, the characteristics of the partner or the number of partners, could elicit or block the action. Although “oral sex”, another example, does not change its name when performed with a partner or a group of partners, the act and the situation is different enough in both scenarios to evoke unlike motivations among individuals. Therefore, a study about sexual behaviour, set of behaviours or repertoires must consider not only the main movement, but also the proximal context or, in other words, the surrounding significant variables which shape the action.

Under that consideration, elaborating a simple list or a complete repertoire can be an almost endless task, including every possible action with every possible partner or group of partners, objects, and combinations of behaviours. For that reason, the present work did not aim to elaborate a repertoire draft in a list format but in a map, or a chart used to include the significant variables that encompass all those possible situations and combinations previously found in the literature.

Method

The present study was divided into two stages. In the first one, we gathered information through a narrative review to compose a preliminary plot of variables. The final proposal was discussed and agreed by all authors in a prior step to the testing phase. Subsequently, the second part consisted in the testing stage, when a set of systematic searches were conducted to validate the preliminary map.

All the information found was analysed trough a thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) and accepted only after consensus of all authors.

This method was chosen to take advantage of the highly developed state of the art on sexual behaviour. Instead of conducting a discovery stage, which could imply massive efforts to screen all the current reports, it was decided to benefit from a narrative review conducted by experts in the field who may draw a sensible picture of the repertoire. Anyway, the standardization comes in a second stage where the model must be tested, and a method is to be set, making available the reproduction and external checking of the results.

Finally, as the aim of the work is not to delineate relations or coefficients, but just a complete map of possible actions, the validation stage requires only to ensure that the plot proposed does not leave any situation given out.

Inclusion Criteria and Labelling

There were not considered any attitudinal variable, in order to keep the information as clear as possible in the meaning of motor behaviour. Furthermore, in both stages, during the process of generating initial codes, searching for themes and reviewing the themes (Braun & Clarke, 2006), variables regarding proximal context were also included, as they provide with important information to record properly the sexual experience.

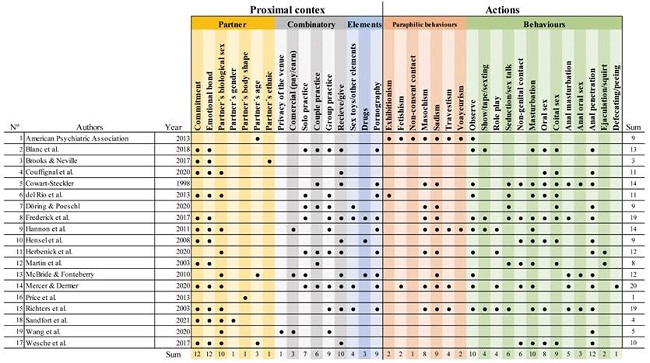

Hence, we finally defined and named 5 groups of variables to define the actions (Table 1) and the relevant proximal context to be able to distinguish every specific movement from another one similar, or even the same one preformed in a completely different scenario (Table 2). These groups included variables about partner's description, combinatory aspects of the behaviour, actions, separated by specific movements and the ones defined as paraphilic (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), and also associated elements, which include objects, drugs or pornography content (Table 1).

All the variables included were reported in prior studies as part of sexual behaviour (Table 1). Nevertheless, we had some special considerations for the partner's description variables after applying thematic analysis principles (Braun & Clarke, 2006).

Initially, we regarded these variables as dependent on the personal perception of each individual. Nevertheless, to sustain the definitions, we included only those variables chosen basing on a reference pointing out common patterns consistently identified through different subjects or samples. This is the case of body shape, studied under the proportion criteria for men and women (Price et al., 2013), or the strength appearance for men (Price et al., 2013; Sell, Lukazsweski & Townsley, 2017). The same criteria were applied with the term of gender expression, totally dependent of the subjective perception but possible to describe in a short of classification previously reported (Sandfort et al., 2021).

Finally, most of the references consulted (Table 1) addressed both emotional bond and stability of the relationship in the same label such as “married”, “stable relationship” or “casual intercourses”, this latter referring to events with partners without emotional bond and commitment. However, after our thematic analysis, we decided to divide bond and commitment into the two separated variables in order to get a more accurate description.

Stage 2

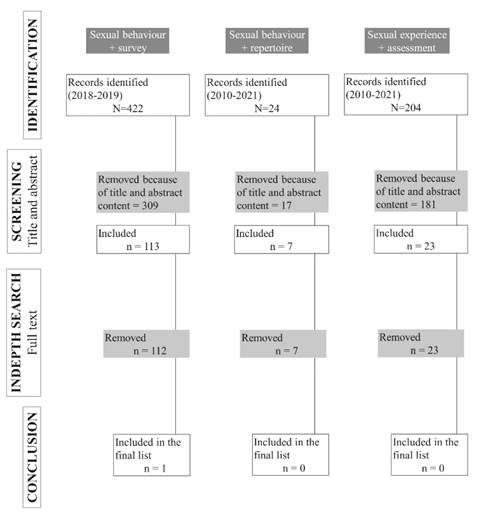

In the second phase, we conducted 3 systematic searches following PRISMA principles (Moher et al., 2010) adapted to the needs of our work (Figure 2). They were carried out in EBSCOhost database (PsycARTICLES, Psychology and Behavioural Sciences Collection, PsycINFO, PSICODOC), both in English and Spanish, including only articles published in peer-review scientific journals, focused on human population, no matter what age, with the search terms in the title and/or abstract.

The first search included the terms “sexual behaviour” + “survey”, from 2018-2021. The second one, oriented to the general pool, including “sexual behaviour” + “repertoire”, from 2010 to 2021. Finally, the third was conducted with the terms “sexual experience” + “assessment”, from 2010 to 2021.

As the objective of the study was not to review the evidence of each behaviour, but only to detect them, this search was not oriented to fully reference every item, but only to identify the ones reported in, at least, one sexual behaviour research. For this reason, to test the preliminary proposal, instead of recording all the information, the process required the continuous comparison between already contained variables or new ones. Then, we selected the reports containing behaviours which did not share exactly the same label on our proposal or were compounded by more than one of our variables, to be analysed trough thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) and assessed for the inclusion.

The risk of bias of the present study lies in the selection of information from a non-unified pool of studies where each author describes verbally each action under their own criteria.

For that reason, the analyses consisted in applying the terms of the thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) given 2 conditions: (coding and theme) the description of the behaviour along with the proximal context only in motor terms, and (analysis) the prospect to describe the same behaviour with the prior components.

Results

After a screening of 650 papers, and an in-depth search in 146 previous studies (113 with terms: “sexual behaviour” + “survey”; 7 with terms “sexual behaviour” + “repertoire”; 23 with terms “sexual experience” + “assessment”), 1 variable was selected for inclusion in the final repertoire.

Then, the discussion led to add the privacy of the venue to the set, concluding that the rest of behaviours were already describable with the preliminary proposal.

Finally, with the decision of including one more variable (privacy of the venue), we obtained a preliminary version of a compilated map of human sexual motor behaviours with 36 items allocated in 5 groups, 3 for the context and 2 for the actions (Table 2).

Table 2. Layer, label and definition of every variable included in the review.

| References number* | Number of references | Layer | Label | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2,3,4,6,8,9,10, 12,14,15,17,18 | 12 | Proximal context/partner | Commitment | Relationship steadiness in time |

| 2,3,4,6,8,9,10, 12,14,15,17,18 | 12 | Proximal context/partner | Emotional bond | Emotional intensity of the relationship between partners |

| 4,6,9,1,16,14,15,17,18,19 | 10 | Proximal context/partner | Partner's biological sex | Biological sex of the partner |

| 18 | 1 | Proximal context/partner | Partner's gender expression | Gender expression in a masculinity-femininity scale |

| 16 | 1 | Proximal context/partner | Partner's body shape | Body proportions/strength/appearance of the partner |

| 1,17,13 | 3 | Proximal context/partner | Partner's age | Age appearance of the partner |

| 3 | 1 | Proximal context/partner | Partner's ethnic | Ethnic physical characteristics of the partner |

| 19 | 1 | Proximal context/combinatory | Privacy of the venue | Sexual intercourse in public or private space |

| 9,13,19 | 3 | Proximal context/combinatory | Commercial (pay/earn) | Exchange of money due to the sex intercourse (pay/earn) |

| 2,6,7,8,11,13,14 | 7 | Proximal context/combinatory | Solo practice | Sexual experience alone |

| 2,5,7,11,12,14 | 6 | Proximal context/combinatory | Couple practice | Intercourse with one person |

| 2,6,7,8,9,11,14,15,19 | 9 | Proximal context/combinatory | Group practice | Intercourse with more than one person |

| 2,4,5,8,10,11,13,14,15,17 | 10 | Proximal context/combinatory | Receive/give | Combinatory feature referring to direction of the action |

| 7,8,14,15 | 4 | Proximal context/elements | Sex toys/Other elements | Use of objects such as specific toys or others to increase sexual arousal or in a specific behaviour |

| 8,10,13 | 3 | Proximal context/elements | Drugs | Drug use in sexual context or with sexual motivation |

| 2,5,6,8,9,11,13,14,15 | 9 | Proximal context/elements | Pornography | Consumption of any kind of audio-visual sexual content |

| 1,6 | 2 | Actions/Paraphilic behaviour | Exhibitionism | Showing the body or any sexual act to a person who does not expect to see it |

| 1,14 | 2 | Actions/Paraphilic behaviour | Fetishism | Experiencing special sexual arousal and acting on any specific object or element |

| 1 | 1 | Actions/Paraphilic behaviour | Non-consent contact | Touching or rubbing on a person who has not complied |

| 1,5,7,8,9,11,14,15 | 8 | Actions/Paraphilic behaviour | Masochism | To be humiliated, tied, hit or any other kind of pain or suffering in sexual context |

| 1,5,7,8,9,11,13,14,15 | 9 | Actions/Paraphilic behaviour | Sadism | Humiliating, tying, hitting, or causing any other kind of pain or suffering in sexual context |

| 1,9,14,15 | 4 | Actions/Paraphilic behaviour | Transvestism | Dressing up with clothes commonly regarded as not typical of people in own biological sex |

| 1,9 | 2 | Actions/Paraphilic behaviour | Voyeurism | Hiddenly observing people nude or in sexual intercourse |

| 1,2,5,6,8,9,11,13,14,15 | 10 | Actions/Behaviour | Observe | Act of staring purposely any erotic scene or content |

| 2,8,9,15 | 4 | Actions/Behaviour | Show/tape/sexting | Act of showing, live or recording, the body and/or any sexual behaviour with erotic intention |

| 9,11,14,15 | 4 | Actions/Behaviour | Role play | Any action of performing and/or dressing pretending to be a determined character in a seduction situation or sexual intercourse |

| 5,6,7,8,12,15 | 6 | Actions/Behaviour | Seduction/sex talk | Any interaction oriented to seduce or increase the sexual arousal |

| 5,8,10,12,14,17 | 6 | Actions/Behaviour | Non-genital contact | Any physical contact not focused on genitals oriented to increase sexual arousal |

| 2,5,6,8,9,10,12,14,15,17 | 10 | Actions/Behaviour | Masturbation | Any manipulation of genitals |

| 2,4,5,6,8,10,15,17 | 8 | Actions/Behaviour | Oral sex | Any oral contact with genitals |

| 2,4,5,6,7,8,10,12,17 | 9 | Actions/Behaviour | Coital sex | Act of vaginal penetration (coitus) |

| 5,8,13,14,15 | 5 | Actions/Behaviour | Anal masturbation | Any anal manipulation |

| 5,13,15 | 3 | Actions/Behaviour | Anal oral sex | Any oral contact with anus |

| 2,4,5,7,8,10,11,13,14,15,17,19 | 12 | Actions/Behaviour | Anal penetration | Act of anal penetration (anal coitus) |

| 11,12 | 2 | Actions/Behaviour | Ejaculation/squirt | Any act of ejaculating or squirting |

| 14 | 1 | Actions/Behaviour | Defecating/peeing | Any act of defecating or urinating with sexual motivation |

*Reference numbers are extracted from order in table 1.

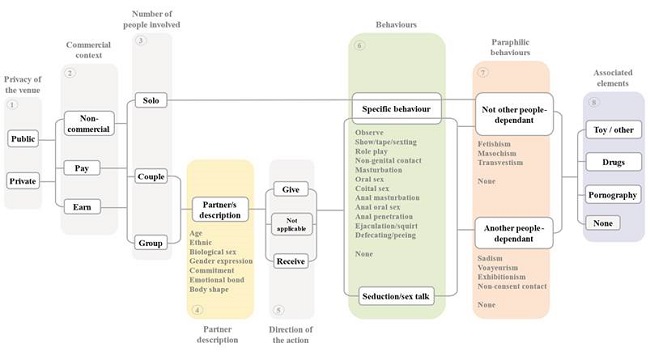

This model is supposed to collect enough information to accurately describe any sexual conduct, allowing a description through a flow chart of 8 layers (Figure 3) corresponding with the five mentioned groups. They are, consecutively, 1) privacy of the venue, 2) commercial context, 3) number of people involved in the situation, 4) partner description, 5) direction of the action, 6) specific behaviour, 7) paraphilic behaviours, and 8) associated elements.

Figure 3. Flowchart of the taxonomical classification of variables included in the definition of sexual behavior.

Of them, layers 1, 2 and 3 are context specifications of each scene, which constitute combinatorial elements, as number 5. Layer 4 gathers variables used for the description of the partner, and the eighth includes possibly associated objects or elements used in the specific behaviours. Finally, 6 and 7 were the specific motor action of the situation.

Discussion

The aim of this paper is to bring in a systematic, exhaustive, and reviewable mapping of human sexual repertoire in terms of motor behaviour. Ideally, this compilation enables to allocate different behaviours in a sustained framework, and to compare them with a wide range of possible observations without the need of elaborating a complete list which, presumably, would be long and more difficult to handle.

There are two main reasons for why this study adds useful information. The first one is simple: in science, gathered knowledge is always suitable to be included in the framework of the field, and allows unification of perspectives for further works. We identified a gap in the basic rationale of several studies across different leisure and health areas, and proposed a piece of information along with the method to review it. As long as it achieves totally or partially the goals, is useful for the scientific knowledge by setting a standard where to consult and compare.

The second reason derives from the explanation of the first one. Sexual behaviour is a usual topic in human life and behavioural research, fact that may lead to the bias of avoiding exhaustive classifications by arguing common sense. Nevertheless, we expect more for scientific research. As we introduced, some papers do not mention sources or selection criteria (e.g. Hensel et al., 2008; Lehmiller et al., 2021; Shilo & Mor, 2020; Wesche et al., 2017; Wylie, 2009), and others validate their choices in the light of their own data without a cited gold standard (Erens et al., 2021; Laumann et al., 2005; Richters et al., 2014). With this review, we propose a framework, for those repeatedly mentioned panels of expert who select behaviours for different research, to be able to not only rely on their advanced knowledge but also in a referenced and reviewed classification.

In that sense, despite the fact that the objective of the present study is not to assess the validity and scope of all those short and large-scale projects introduced, this discussion brings up the question of adequacy of the repertoires, which are often different in extension and inclusion (Table 1) (Herbenick et al., 2010).

Thereby, the absence of a common framework impedes in some term to draw parallels between populations. In psychopathology, for example, it is widely acknowledged that symptoms are backed up by an exhaustive classification of symptomatic behaviours related to each other, which are, likewise, based in studies that enable them to enter that frame, and are constantly revisited. Then, we can compare a psychopathological action given within a validated group of actions.

However, in sexual behaviour we have not been able to find out any short of complete list, map, flowchart or cluster proposal. Under the argument of its intrinsic difficulty, it has been ignored. Thus, can we really develop models and rely on the coefficients without been totally sure of the extension of our surveys?

Although, we insist, it is not the objective of the present report to globally assess the quality of the national-scale surveys FINSEX (Kontula, 2009, 2015), NHSLS (Lauman et al., 2001), NSSHB (Herbenick et al., 2010), NATSAL (Erens et al., 2021) and ASHR (Smith et al., 2003), we still have the feeling of lacking information about the baseline selection of specific behaviours, and the consistency among projects in labelling, choosing and defining. Indeed, Herbenick et al. (2017) mention item differences among those surveys.

Furthermore, we uphold as another contribution of our work the contextual consideration of the behaviours. For example, in terms of motor behaviour, a man masturbating himself alone in a private venue is not equal than a man masturbating in group in a public venue and showing it to people who do not expect to see it. Evidently, it is possible to describe that scene in separated labels although the motor act of the person is, indeed, the same action. This example perfectly draws the importance of pointing out the proximal context because it allows a precise comparison and a proper distinction.

As explained above, we included four layers to describe the eliciting variables (1, 2, 3, 4 in Figure 3) one more for the use of associated elements or objects for the sexual behaviour (8 in Figure 3), another for the direction of each action, if necessary (5 in Figure 3), and two of specific behaviours which constitute the nuclear information of every scene traditionally mentioned isolated.

Then, different strategies can be used to inform about the full situation, such as following the path (Figure 3) for every conduct in a specific date, or reporting about each category for a scene given, where more than one option can be chosen. It is also possible to gather information about avoiding trends or motivational experience for every variable, or simply answer about variables experienced. The main point is that, under this criterion, every report can be delimited and explained within same conditions given, and every subject can be assessed within the same full set of categories, enabling then good comparisons between studies and accurate description within a broad scope.

If a group of authors consider a specific set of behaviours for their research, they should provide either an exhaustive screening of possible situations, or an explanation or reference for why they select only a shorter list of them. Otherwise, the limitation of cherry-picking ones and not the others should be indicated.

We conclude that following this path and applying it to new studies is a suitable way to standardize sexual research and allow a deeper understanding of human sexual behaviour.

Conclusion

With the present work, we report how we developed, referenced, defined, and preliminary tested a useful taxonomy of human sexual behaviour, along with the method to increase the quality of sexual research and address the methodological issue traditionally avoided.

This result, anyway, is not a closed form, but a dynamic framework susceptible to review, redefine and retest in order to get improvements and to assure the exhaustiveness of the data collected.

Limitations

A preliminary search of “sexual behaviour” in EBSCOhost database (PsycARTICLES, Psychology and Behavioural Sciences Collection, PsycINFO, PSICODOC), in both English and Spanish and including only articles published in peer-review scientific journals focused on human population, no matter what age from 2000-2021, turns up in 59760 papers. This is only regarding the last twenty years, and by far is not all of the sexual behaviour research, so we discuss that the final validation of our classification requires a huge effort to compare with several sources and ensure about the complexity of the final outcome.

We began from an expert panel consideration of sexual behaviour alongside with the references needed, and a preliminary testing stage afterwards, so that we could get to a renewable model which is susceptible of amendments for a robust outcome. Our proposal contains what we considered necessary to present a preliminary version but, anyway, we regard the importance of further research to validate it completely.