Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO  Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

versión impresa ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.96 no.8 Madrid ago. 2004

| ORIGINAL PAPERS |

Retreatment and maintenance therapy with infliximab in fistulizing Crohn' disease

L. Rodrigo, J. M. Pérez-Pariente, D. Fuentes, V. Cadahia, A. García-Carbonero, P. Niño, R. de Francisco, R. Tojo, M. Moreno

and E. González-Ballina

Service of Digestive Diseases. Hospital Central de Asturias. Oviedo. Spain

ABSTRACT

Objectives: infliximab has clearly demonstrated its efficacy in the short-term treatment of fistulizing Crohn' disease. We present here the results of retreatment and long-term maintenance therapy.

Patients and methods: eighty one consecutive patients with active fistulizing Crohn' disease, in whom previous treatments had failed, were treated with infliximab. All patients received as the initial treatment of 5 mg/kg i.v. infusions (weeks 0, 2, and 6). Those patients who failed to respond after the initial cycle (group 1, n= 25), or those who relapsed after having responded (group 2, n=13), received retreatment with three similar doses (weeks 0,2, and 6). Those who responded to retreatment were included in a long-term maintenance programme (n=44), with repeated doses (5 mg/kg i.v. infusions) every eight weeks for 1-2 years.

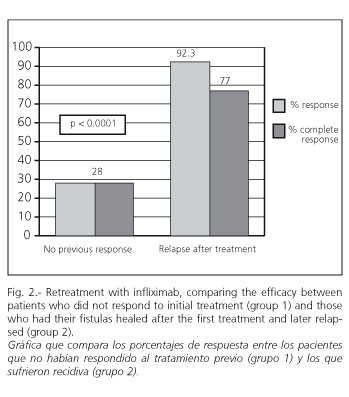

Results: in the initial treatment 56% of the patients responded partially; this response being complete in 44%. In the retreatment, 28% of group 1 (non-responders) presented a complete response, compared to 77% in group 2 (relapsers) (p< 0.0001). In the maintenance treatment, the global response was 88% (39/44). The mean number of doses per patient was 4.4 ± 2 (range 1-9) with a duration of 36 ± 12 weeks (range 8-72). Adverse effects were not significantly increased in either treatment.

Conclusions: both retreatment and long-term maintenance therapy with infliximab, are highly effective and well tolerated in fistulizing Crohn' disease patients.

Key words: Retreatment. Maintenance therapy. Infliximab. Fistulizing Crohn' disease.

Rodrigo L, Pérez-Pariente JM, Fuentes D, Cadahia V, García-Carbonero A, Niño P, de Francisco R, Tojo R, Moreno M, González-Ballina E. Retreatment and maintenance therapy with infliximab in fistulizing Crohn' disease. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2004; 96: 548-558.

Recibido: 13-11-03.

Aceptado: 27-01-04.

Correspondencia: Luis Rodrigo. Servicio de Aparato Digestivo. Hospital Central de Asturias. C/ Celestino Villamil, s/n. 33006 Oviedo. e-mail: lrodrigos@terra.es

INTRODUCTION

Crohn' disease (CD) causes inflammation of the full thickness of the bowel wall and may involve any part of the gastrointestinal tract.

This disease may present various local complications including the presence of fistulas, both internal (entero-enteric, entero-vesical, etc.) and external (perianal, entero-cutaneous, etc.).

Various medical treatments have been employed for the management of CD, amongst which are corticosteroids, aminosalicylates, antibiotics and immunosuppressants, alone or in combination.

Various investigators have shown that the production of TNFα is increased both in the serum and in intestinal mucosa of patients with CD (1,2). Infliximab (Remicade®) is a human-murine chimeric monoclonal antibody, which is capable of joining the soluble and transmembrane forms of TNFα, blocking their interaction with receptors, neutralizing its biological activity (3,4), and inducing a local immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory action (5-7).

Several studies have demonstrated the efficacy of infliximab in the treatment of CD, both in inflammatory forms (8) and in cases with associated fistulas (9).

Although its efficacy in the short-term control of fistulous disease has been well demonstrated, in the medium-term (around 12 weeks), a considerable number of patients present with relapses. Several investigators have attempted to find factors related to individual variability in response and its duration (10-14). Up to the present it has not been possible to identify clinically useful predictors.

The approach to follow in medium-term treatment is a subject open to debate, on which there is little experience for the time being.

The aim of this study is to describe our experience in the treatment of fistulizing CD with infliximab in the long-term, including retreatment and maintenance therapy.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

From April 1999 to the present day, a total of 81 consecutive patients with fistulizing CD have been treated with infliximab. A diagnosis of CD was confirmed by means of clinical, endoscopic, radiological and histological criteria according to Lennard-Jones (15).

Patients were informed of the state of their disease and of the different therapeutic possibilities, and at the same time they received detailed information about the characteristics of infliximab and its adverse effects; a written informed consent was obtained. Prior to the intravenous infusion, a tuberculin test and chest radiograph, were obtained for all patients. The protocol and treatment regimen were approved by the Ethics Committee of our hospital.

The indication established for the treatment in our series was the presence of fistulizing CD, with active drainage for at least three months, prior to the infusion of infliximab, in spite of the use of previous treatments with different drugs (aminosalicylates, antibiotics, immunosuppressants, etc.), and patients were included consecutively on attending our department (both inpatients and outpatients).

For the evaluation of fistulous disease, a physical examination of the perianal region was performed, together with total colonoscopy, endoanal sonography and magnetic resonance of the pelvis, in order to assess the number, site and activity of fistulas.

Eighty-nine percent of patients had been previously treated with a standard dose of azathioprine (2.5 mg/kg/day for 28 ± 26 months, range 6-120).

Infliximab was intravenously infused, at a dose of 5 mg/kg for two and a half hours, following the manufacturer' instructions (Schering-Plough Laboratories, USA), in three doses separated by usual intervals (weeks 0, 2 and 6). Our day hospital was used for this purpose.

Patients remained there for 6 hours, during which time vital signs were controlled. All patients were clinically observed every 15-30 minutes for the possible appearance of adverse effects, both during the intravenous infusion and during the 3 following hours. Patients were then discharged and followed-up by phone, every 24 hours for 3 days.

Any clinical event which occurred during the intravenous infusion, observation period, and later follow-up, was recorded. Periodic checkups were made at weeks 2 and 4 after the intravenous infusion, and later every 4 weeks or when the patient experienced any complication or clinical change in the disease, and when she/he attended our department.

Physical examination, blood count and biochemical analysis including acute phase reagents were obtained in each visit, and alterations in the course of the disease, such as the appearance of flare-ups, changes in the number and activity of fistulas, and/or development of other possible complications related to the disease (abscesses, suboclusive episodes, etc.) were recorded in detail.

In cases where doubts existed regarding the closure of fistulous tracts, the opening of new ones, or the possibility of new complications related to the abovementioned events, imaging studies (endoanal sonography and/or pelvic magnetic resonance) were repeated.

For the evaluation of results, response was considered as the closure of at least 50% of the fistulas existing at the beginning of treatment, and complete response was the closure of all fistulas.

From February 2000 retreatment was begun by administering three new doses in an attempt to obtain a response in those patients who had not achieved a response to initial treatment (group 1, n = 25) and in those who had responded and later relapsed (group 2, n = 13). Eleven patients refused retreatment for the following reasons: refusal due to lack of efficacy (n = 6) or submission to surgery (n = 5).

From March 2001 a maintenance program was begun for those patients who had responded (both after the initial cycle and after retreatment). In this case, a single i.v. infusion of 5 mg/kg was administered every 8 weeks. This included a total of 44 patients, of whom 19 had previously undergone retreatment, while 25 had entered directly from initial treatment (Fig. 1).

No control group was available, as we included all responding patients in this program. We did not administer premedication with corticosteroids and/or anti-histaminics prior to the i.v. infusion of new doses of infliximab.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, and qualitative variables as percentages. For the analysis of the results obtained Student' t test was used for quantitative data and the Chi square test with Fisher' correction for qualitative data and percentages. Data not following a homogeneous distribution were analysed using non-parametric techniques (Mann-Whitney U and Kruskal-Wallis). For the analysis of the different demographic factors a multivariate analysis was performed. A p ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The statistical package SPSS, version 11.0 (SPSS. Inc) was employed for the analysis of data.

RESULTS

Patients were grouped in accordance with the classification of Vienna. The site of the majority of fistulas was perianal (80%). Other variables such as gender, toxic habits and duration of disease and fistulas were collected and are shown (Table I).

Results of the initial treatment

A response was achieved in 55.6% of patients (45/81) in week 2.1 ± 1. Response was complete in 44.4% of cases (36/81), this being reached in week 2.5 ± 1.

None of the 4 patients with associated enterovesical fistulas and only one of the 4 patients with enterovaginal fistulas presented closure. On analysing the characteristics of responders compared to non-responders no significant differences were found.

The duration of the disease approached significance (p = 0.05), this being longer for non-responders (9.6 ± 7.6 vs 6.3 ± 6 years) (Table II).

Retreatments

Group 1 (n = 25): a response was only found in 28% (7/25) in week 2.4 ± 1.2. Response was complete in all of these. Of these patients, 3 corresponded to cases in which azathioprine was administered after the infusion of the first infliximab course. No statistically significant differences were observed between responders and non-responders. Responders were later included in the maintenance program.

Group 2 (n = 13): response was achieved in 92.3% of cases (12/13), and complete response in 77% (10/13). Responders were similarly included in the maintenance program.

On comparing the percentage of responses between groups 1 and 2, statistically significant differences were observed (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 2).

Maintenance therapy

Out of a total of 44 patients treated only 5 relapsed. The maintenance index to the initial response was 88% (39/44), with a mean number of doses of 4.4 ± 2 per patient (range 1-9) (Fig. 3), which is equivalent to 36 ± 12 weeks (8-72 weeks). Week 0 for maintenance treatment was considered the beginning of the new treatment (Fig. 4).

Adverse effects

The main adverse effects observed are shown in figure 5. Three cases of pulmonary tuberculosis were observed. The tuberculin test and chest X-ray prior to treatment had been negative; two cases appeared after initial treatment and one after retreatment, all of which were completely cured after specific treatment. The i.v. infusion was stopped in two patients - in one due to subjective dyspnea, and in the other one, due to an anaphylactic reaction, which was controlled satisfactorily with standard medical treatment (antihistaminics and corticosteroids). The latter case was a patient who underwent a second dose of retreatment, 7 months after the first cycle.

In our series we did not observe a significant increase in the usual complications with the administration of retreatment or maintenance therapy.

During maintenance treatment we observed intermittent development of antinuclear antibodies (ANA) in 11 of 45 patients (25%), none of whom presented a "lupus-like" reaction.

DISCUSSION

Treatment with infliximab has demonstrated its efficacy in the management of patients with CD, both in controlled and in placebo studies (16), and in daily practice since commercialization. A number of questions initially raised have been partially answered, although some, whose answer has not been conclusively established, especially those concerning long-term management with this type of medication, remain unsolved.

The efficacy of infliximab in the closure of fistulas in CD has also been compared to placebo (17), and has clearly shown its superiority in controlled studies, including those using immunosuppressants (18,19).

On analyzing the results obtained with the first cycle of treatment we observed a response rate of 55.6%. These results are slightly smaller than those published in series such as those from the Mayo Clinic (20) (69%), or those obtained by Farrel et al. (21) (65%), and similar to other series (22).

The percentage of patients who presented a complete response (44.4%) was also similar to the above-mentioned series, and greater than those obtained by Cohen et al. (23) (24% at week 3), this being probably due to the fact that in this series only 38% of patients received three complete doses.

With respect to the clinical and laboratory characteristics of patients, no significant differences were seen for the majority of these factors, between responders and non-responders, which is in agreement with other studies (24,25). The duration of disease approached significance, probably due to the small size of the sample. This, in our series, is slightly greater among non-responders (p = 0.05).

In a recent publication (26) a greater response rate has been reported for younger patients with chronic involvement and concomitant use of immunosuppressants. Other studies, however, have suggested a possible greater duration of response in non-smokers, although no differences were found in the percentage of initial response (27).

Several studies report a greater percentage of response in patients previously treated with azathioprine. In the retreatment phase we observed a lower percentage of response in group 1 (28%), which supports the idea of "giving a second opportunity to these patients", although it is important to emphasize that 3 of these 7 responding patients corresponded to those who did not receive immunosupressive treatment during the first cycle, and it is possible that this percentage could be greater than that observed had azathioprine been employed (28).

In group 2, we obtained a higher percentage of responses (92.3%), which was significantly greater to that achieved in group 1. We therefore think that retreatment of a patient previously treated with infliximab who experienced closure and later reopening of fistulas (as usually occurs in the majority of cases in which only the initial cycle is administered) has a high possibility of achieving a new closure.

Since the mean duration of response in patients with fistulas is around 12 weeks after initial treatment (17) we studied the effect of the i.v. infusion of repeated doses on the maintenance of response. Recent studies exist which show its efficacy, especially in the case of active inflammatory disease (29), such as ACCENT-1, a multicenter study with 573 patients (30), whose results show that maintenance treatment with infliximab in the inflammatory form of the disease, is highly effective, safe and well tolerated. Other previously published clinical series report the possibility that these results can also be obtained in fistulizing CD (20).

In our study, we confirmed this hypothesis, since the majority of patients who achieved an initial response, and who were included in the maintenance program, presented a prolonged closure of fistulas (88%).

With respect to the safety of the medication, our findings are in accordance with results obtained elsewhere -in controlled clinical trials, other clinical series and reviews (31)- and we did not observe a significant increase in adverse reactions with the administration of successive new doses.

One patient presented a moderate anaphylactic reaction, which was controlled satisfactorily with standard medical treatment. This patient was a 20-year-old female, who had received a previous cycle of three doses with complete response and later relapse, for which reason it was decided to give another cycle, 7 months after the initial one; she presented this reaction after the first dose of the second cycle. In order to decrease this risk, we recommend restricting the time between cycles, since a prolonged period between doses appears to increase the percentage of such reactions (32).

Regarding the development of infections, the significant number of cases of tuberculosis described in the literature in relation to this medication (33) makes it necessary to bear in mind the possibility of such complication during treatment, especially in countries with a high prevalence of tuberculosis.

Other significant infectious complications were the development of three perianal abcesses and two abdominal ones, probably due to the fact that all patients presented active fistulas. We performed a systematic drainage of all possible perianal abscesses, prior to beginning treatment with infliximab, and provided antibiotics in all cases where it was necessary. Other adverse effects included community pneumonia and esophageal candidiasis, probably due to the use of concomitant immunomodulatory drugs (as several authors suggest) rather than to infliximab, despite the fact that several studies show a greater frequency of infections with infliximab alone (34).

We did not observe any tumors or lymphoproliferative disorders. Although similar to other studies (35) a percentage of patients exhibited ANA positivization during treatment with repeated doses, but no related complications were seen (lupus, lupus-like or collagenosis).

Finally, we wish to emphasize the medium- to long-term efficacy of retreatment and maintenance therapy in fistulizing CD, although future studies and longer follow-ups will be necessary in order to draw more definitive conclusions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to thank David H. Wallace (Member of the European Association of Science Editors) for the English language translation of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

1. Reimund JM, Wittersheim C, Dumont S, et al. Mucosal inflammatory cytokine production by intestinal biopsies in patients with ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. J Clin Immunol 1996; 16: 144-50. [ Links ]

2. Breese EJ, Michie CA, Nicholls SW, et al. Tumor necrosis factor alpha-producing cells in the intestinal mucosa of children with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 1994; 106: 1455-66. [ Links ]

3. Scallon BJ, Moore MA, Trinh H, et al. Chimeric anti-TNF-alpha monoclonal antibody cA2 binds recombinant transmembrane TNF-alpha and activates immune effector functions. Cytokine 1995; 7: 251-9. [ Links ]

4. Siegel SA, Shealy DJ, Nakada MT, et al. The mouse/human chimeric monoclonal antibody cA2 monoclonal antibody cA2 neutralizes TNF in vitro and protects transgenic mice from cachexia and TNF lethality in vivo. Cytokine 1995; 7: 15-25. [ Links ]

5. Cornillie F, Shealy D, D'Haens G, et al. Infliximab induces potent anti-inflammatory and local immunimodulatory activity but not systemic immune suppression in patients with Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2001; 15: 463-73. [ Links ]

6. Ten Hove T, Van Montfrans C, Peppelenbosch M, et al. Infliximab treatment induces apoptosis of activated lamina propria T-lymphocytes in Crohn' disease. Gut 2002; 50: 206-11. [ Links ]

7. Baer FJ, D'Haens GR, Peeters M, et al. Tumor necrosis factor alpha antibody (infliximab) therapy profoundly down-regulates the inflammation in Crohn's ileocolitis. Gastroenterology 1999; 116: 22-8. [ Links ]

8. Rutgeerts PJ. Review article: Efficacy of infliximab in Crohn's disease-induction and maintenance of remission. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1999; 13: 9-15. [ Links ]

9. Present DH. Review article: the efficacy of infliximab in Crohn's disease-healing of fistulae. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1999; 13: 23-8. [ Links ]

10. Martínez-Borra J, López-Larrea C, González S, et al. High serum tumor necrosis factor-alpha levels are associated with lack of response to infliximab in fistulising Crohn' disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2002; 97: 2350-6. [ Links ]

11. Mascheretti S, Hampe J, Croucher PJ, et al. Response to infliximab treatment in Crohn' disease is not associated with mutations in the CARD15 (NOD2) gene: an analysis in 534 patients from two multicenter, prospective GCP-level trials. Pharmacogenetics 2002; 12: 509-15. [ Links ]

12. Vermeire S, Louis E, Rutgeers P, et al. NOD2/CARD15 does not influence response to infliximab in Crohn' disease. Gastroenterology 2002; 123: 106-11. [ Links ]

13. Esters N, Vermeire S, Joossens S, et al. Serological markers for prediction of response to anti-tumor necrosis factor treatment in Crohn' disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2002; 97: 1458-562. [ Links ]

14. Nikolaus S, Raedler A, Kuhbacker T, et al. Mechanisms in failure of infliximab for Crohn' disease. Lancet 2000; 356: 1475-9. [ Links ]

15. Lennard-Jones JE. Classification of inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl 1989; 170: 2-6. [ Links ]

16. Targan SR, Hanauer SB, van Deventer SJ, et al. A short-term study of chimeric monoclonal antibody cA2 to tumor necrosis factor alpha for Crohn's disease. Crohn's disease cA2 Study Group. N Engl J Med 1997; 337: 1029-35. [ Links ]

17. Present DH, Rutgeerts P, Targan S, et al. Infliximab for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med 1999; 340: 1398-405. [ Links ]

18. Present DH, Korelitz BI, Wisch N, et al. Treatment of Crohn' disease with 6-mercaptopurine: a long-term, randomised, double-blind study. New Engl J Med 1980; 302: 981-7. [ Links ]

19. Pearson DC, May GR, Fick GH, et al. Azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine in Crohn's disease: A meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 1995; 123: 132-42. [ Links ]

20. Ricart E, Panaccione R, Loftus EV, et al. Infliximab for Crohn's disease in clinical practice at the Mayo Clinic: The first 100 patients. Am J Gastroenterol 2001; 96: 722-9. [ Links ]

21. Farrell RJ, Shah SA, Lodhavia PJ, et al. Clinical experience with infliximab therapy in 100 patients with Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2000; 95: 3490-7. [ Links ]

22. Ardizzone S, Colombo E, Maconi G, et al. Infliximab in treatment of Crohn' disease: the Milan experience. Dig Dis Sci 2002; 34: 411-8. [ Links ]

23. Cohen RD, Tsang JF, Hanauer SB. Infliximab in Crohn's disease: first anniversary clinical experience. Am J Gastroenterol 2000; 95: 3469-77. [ Links ]

24. Feffeman DS, Lodhavia PJ, Reinert S, et al. Smoking, age, duration of disease, gender, and other clinical factors do not predict response to infliximab in Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 2001; 120: A619. [ Links ]

25. Sample C, Bailey RJ, Todoruk D, et al. Clinical experience with infliximab for Crohn's disease: The first 100 patients in Edmonton, Alberta. Can J Gastroenterol 2002; 16: 165-70. [ Links ]

26. Vermeire S, Louis E, Carbonez A, et al. Demographic and clinical parameters influencing the short-term outcome of anti-tumor necrosis factor (infliximab) treatment in Crohn' disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2002; 97: 2357-63. [ Links ]

27. Parsi MA, Achkar JP, Richardson S, et al. Predictors of response to infliximab in patients with Crohn' disease. Gastroenterology 2002; 123: 707-13. [ Links ]

28. Ochsenkuhn T, Goke B, Sackmann M. Combining infliximab with 6-mercaptopurine/azathioprine for fistula therapy in Crohn' disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2002; 97: 2022-5. [ Links ]

29. Rutgeerts P, D'Haens G, Targan S, et al. Efficacy and safety of retreatment with anti-tumor necrosis factor antibody (infliximab) to maintain remission in Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 1999; 117: 761-9. [ Links ]

30. Hanauer SB, Feagan BG, Lichtenstein GR, et al. Maintenance infliximab for Crohn' disease: the ACCENT I randomised trial. Lancet 2002; 359: 1541-9. [ Links ]

31. Hanauer SB. Review article: Safety of infliximab in clinical trials. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1999; 13: 16-22. [ Links ]

32. Kugathasan S, Levy MB, Saeian K, et al. Infliximab retreatment in adults and children with Crohn' disease: risk factors for the development of delayed severe systemic reaction. Am J Gastroenterol 2002; 97: 1408-14. [ Links ]

33. Keane J, Gershon S, Wise RP, et al. Tuberculosis associated with infliximab, a tumor necrosis factor a-neutralizing agent. New Engl J Med 2001; 345: 1098-103. [ Links ]

34. Sandborn WJ, Haunauer SB. Antitumor necrosis factor therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: a review of agents, pharmacology, clinical results, and safety. Imflamm Bowel Dis 1999; 5: 119-33. [ Links ]

35. Vermeire S, Norman M, Van Assche G, et al. Infliximab (Remicade) treatment in Crohn' disease and antinuclear antibody (ANA) formation. Gastroenterology 2001; 120: A69. [ Links ]

texto en

texto en