Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

versión impresa ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.101 no.9 Madrid sep. 2009

Bilateral pulmonary thromboembolism and Budd-Chiari syndrome in a patient with Crohn's disease on oral contraceptives

Tromboembolismo de pulmón bilateral y síndrome de Budd-Chiari en paciente con enfermedad de Crohn y toma de anticonceptivos orales

M. Valdés Mas, C. Martínez Pascual, J. Egea Valenzuela, M. C. Martínez Bonil, A. M. Vargas Acosta, M. L. Ortiz Sánchez, M. Miras López and F. Carballo Álvarez

Service of Digestive Diseases. Virgen de la Arrixaca University Hospital. El Palmar, Murcia. Spain

ABSTRACT

Budd-Chiari syndrome can be defined as an interruption or diminution of the normal blood flow out of the liver. Patients with Budd-Chiari syndrome present with varying degrees of symptomatology that can be divided into the following categories: fulminant, acute, subacute and chronic. The subacute form is the most common presentation. A majority of patients with Budd-Chiari syndrome have an underlying hypercoagulability state. We present the case of a young woman with Crohn's disease on oral contraceptives who developed bilateral pulmonary thromboembolism and Budd-Chiari syndrome.

Key words: Budd-Chiari syndrome. Oral contraceptives. Crohn's disease. Bilateral pulmonary thromboembolism.

RESUMEN

El síndrome de Budd-Chiari consiste en la interrupción o disminución de flujo de las venas suprahepáticas. Tiene una gran variabilidad clínica en cuanto a su forma de presentación siendo la más frecuente la forma subaguda. La gran mayoría de los pacientes responden a estados de hipercoagulabilidad. Presentamos el caso de una paciente joven con enfermedad de Crohn que estaba en tratamiento con anticonceptivos orales y desarrolló un cuadro clínico de tromboembolismo de pulmón bilateral y síndrome de Budd-Chiari.

Palabras clave: Síndrome de Budd-Chiari. Anticonceptivos orales. Enfermedad de Crohn. Tromboembolismo de pulmón bilateral.

Case report

Herein we present the case of a twenty-year-old woman from Morocco who has been living in Spain for two years. She had a past history of non-diagnosed chronic diarrhea and a premature birth. She has taken oral contraceptives (OCs) (ethynylestradiol 75 mg/d) for the last two years, and one of her sisters was recently diagnosed with Crohn's disease (CD).

She was admitted to hospital with fever, abdominal pain and diarrhea of 2 weeks' duration. Physical examination revealed a temperature of 38.7 ºC and pain in the left inguinal region. Forty-eight hours later the patient began with progressive abdominal distension and dyspnea.

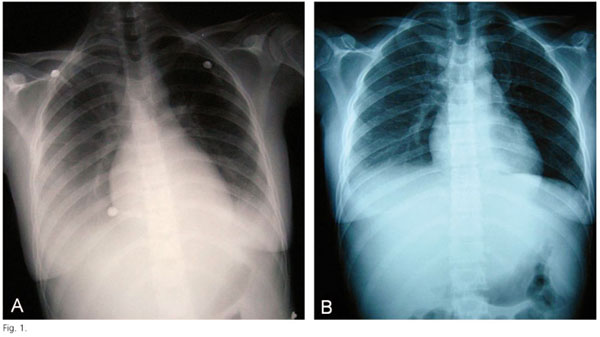

Chest X rays showed bilateral pleural effusion (Fig. 1). Abdominal X-rays were normal. Abdominal ultrasonography showed a big amount of ascites, bilateral pleural effusion, and an increased colon wall. Computed thoraco-abdomino-pelvic tomography corroborated the bilateral pleural effusion and showed a bilateral pulmonary thromboembolism, and an increased caudate lobe in the liver with ischemic diffuse areas and thrombosis of the right supra-hepatic vein (Fig. 2). Echocardiography was normal.

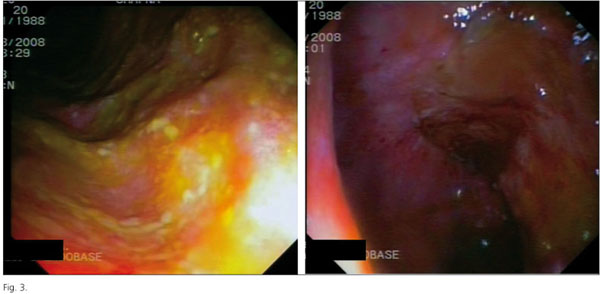

Colonoscopy revealed multiple ulcers in the rectum and sigma with an edematous mucosa of the entire colon. The diagnosis of CD was confirmed by histological findings (Fig. 3).

Laboratory findings were as follows: hemoblobin 8.4 g/dl, platelets 80,000 U/l, white blood cells 16,500 U/l (N: 80%), prothrombin activity 47%, GSV 30 mm/h, ALT 62 U/l, AST 43 U/l, ALP 95 U/l, GGT 77 U/l, DHL 487 U/l, serum albumin 2.4 g/dl, total proteins 5.4 g/dl, and CRP 13.4 mg/dl. Non-organ specific antibodies, rheumatoid factor and iron metabolism were all normal. Blood and stool cultures were also normal.

Serologic tests for HBV, HCV, HIV, toxoplasm, lues, hydatidosis and Coxiella were negative. HAV, CMV and EBV had positive IgGs. Antiglycoprotein antibodies gASCA, ALCA, and AMCA were negative, and ACCA was positive.

Taking together all these results we report the case of a young woman with recently diagnosed CD, bilateral pulmonary thromboembolism and Budd-Chiari syndrome (BCS) who had had a recent pregnancy and was on oral contraceptives.

Total parenteral nutrition, oxygen, prednisolone, mesasalazine, spironolactone, furosemide, meropenem, and low molecular weight heparin were started.

In the following forty-eight hours her fever, abdominal pain and diarrhea disappeared, and her ascites was well controlled with medical treatment.

Discussion

BCS can be defined as a pathophysiologic process that results in an interruption or diminution of normal blood flow out of the liver (1). BCS implies thrombosis of hepatic veins and/or the intrahepatic or suprahepatic inferior vena cava (IVC) (2). It can also be described as the occlusion or partial occlusion of IVC. It is more frequent in women (67 percent) between thirty and forty years of age (1,3).

Obstruction is usually caused by a thrombus, but may result from extrinsic IVC compression (4). It may also be a postoperative complication following liver transplantation (5-7). Membranous webs within IVC and hepatocellular carcinoma are less frequent causes (8,9).

Posthepatic obstruction leads to increased sinusoidal pressure, sinusoidal congestion, hepatomegaly, hepatic pain, portal hypertension and ascites (4,8). Caudate lobe hypertrophy may further compress IVC, and can occur in up to 50 percent of chronic presentations (8).

A majority of patients with BCS present with hepatomegaly, right upper quadrant pain, and abdominal ascites. Some patients may feature signs of portal hypertension such as variceal bleeding and refractory ascites with a high serum-ascites gradient (> 1.1 g/dl) (10,11).

Patients with BCS present with varying degrees of symptomatology. Patients can be divided into the follow-ing categories: fulminant, acute, subacute and chronic (12). The subacute form is the most common presentation, in 40 percent of patients, and is characterized by a slow accumulation of ascites. In the fulminant form (7 percent of patients) hepatic encephalopathy develops within eight weeks of jaundice onset. An acute onset occurs in 28 percent of patients, with a short duration of symptoms and intractable ascites. Collateral venous channels do not develop in the acute form of BCS; forty percent of patients develop a chronic form that usually occurs in the presence of cirrhosis (13).

An underlying disorder can be identified in over 80 percent of patients with BCS (14). Many of these disorders are characterized by a hypercoagulability state. As many as 50 percent of all cases of BCS may be due to an underlying chronic myeloproliferative disorder such us polycythemia vera, essential thrombocytemia, or agnogenic myeloid metaplasia (15,16).

Malignancies account for approximately 10 percent of cases of BCS. Direct compression or invasion of vascular structures and the hypercoagulability state are associated with malignancy. Hepatocellular carcinoma is found most often, followed by adrenal gland or kidney malignancies (17).

Nearly twenty percent of cases of BCS occur in women who have been on oral contraceptives, for as little as two weeks. It is presumed that the hypercoagulable state in these women is responsible for this association (18,19).

A number of other hypercoagulable states have been associated with BCS. These include factor V (Leiden) gene mutation, factor II gene mutation, antiphospholipid syndrome, and protein C and S deficiency (20,21).

Less frequent causes are Behçet's syndrome, partial or complete membranous IVC obstruction, systemic lupus erythematosus, mixed connective tissue disease, and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (17,22-24).

The diagnosis is suspected from clinical signs, symptoms and radiographic findings. Imaging modalities are Doppler ultrasounds, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging. Radiographic findings seen in BCS include non-homogeneous parenchymal enhancement, presence of intrahepatic collaterals, and caudate lobe hypertrophy. Magnetic resonance imaging may differentiate chronic from acute disease. Other investigations that may aid in management include hepatic venography and liver biopsy (25,26).

The treatment of BCS generally follows a least invasive to most invasive strategy. This algorithm includes medical management, recanalization, TIPS, and liver transplant.

Medical management consists of anticoagulation, sodium restriction, diuretic therapy and paracentesis (27). Early use of streptokinase, urokinase, angioplasties, or vascular stents can be vital in stopping the progression of the disease (28,29). TIPS has become the first option when a shunting procedure is indicated (30). Liver transplant is indicated for patients with fulminant liver failure or cirrhosis and decompensated disease (31).

Approximately 25 percent of patients remain asymptomatic after treatment. Florid clinical presentation, male sex, older age, no TIPS performed, high Child-Turcotte-Pugh, and high serum creatinine are factors that adversely affect survival in BCS (32,33).

We present the case of a young woman with bilateral pulmonary thromboembolism, BCS, and CD who had been on OCs for the last eight months.

Concern about OC toxicity initially limited the long-term use of these drugs. Most important side effects include thromboembolic events and cardiovascular disease (34,35). Older age and tobacco use may increase the risk of adverse events. Most frequent cardiovascular events are coronary heart disease, arterial hypertension and stroke. An increase in the risk of venous thromboembolic dis-ease is seen with both high- and low-dose estrogen OC preparations. The risk of thromboembolism may be higher with third-generation progestin, desogestrel and gestodene (36-38).

Contraceptive patches may be associated with a higher risk of thromboembolism; intravenous patches have the highest risk.

More than a hundred various extraintestinal complications of ulcerative colitis and CD have been found and described so far (28). The incidence of thromboembolic complications with inflammatory bowel disease was 1.3-39 percent (29). In a majority of patients, thrombosis is associated with a hypercoagulable state associated with increased levels of thromboplastin, fibrinogen, and factor VII, as well as with elevated platelet counts. It may also be possibly caused by protein S and C deficiencies. Coagulation abnormalities have been observed in 60 percent of cases in series of patients with ulcerative colitis and CD. Malignancy, myeloproliferative disorders or OC use are other important factors (39,40).

A majority of patients in the literature are young women with ulcerative colitis (28,29,39,41,42) and less frequently with CD (40,42,43).

The most common sites for venous thrombosis in inflammatory bowel disease is pulmonary vasculature, pelvis, and the deep veins in the legs. An involvement of the splenic, portal, renal and central nervous systems has been described. Hepatic vein thrombosis has rarely been reported (39,41).

In patients with inflammatory bowel disease, OCs can be maintained in women who are doing well. Cessation should be considered for those women who remain symptomatic despite conventional drug therapy or have OC-related adverse effects (44).

References

1. Tilanus W. Budd-Chiari syndrome. Br J Surg 1995; 82: 1023. [ Links ]

2. Okuda K, Kage M, Shrestha SM. Proposal of a new nomenclature for Budd-Chiari syndrome: hepatic vein thrombosis versus thrombosis of the inferior vena cava at is hepatic portion. Hepatology 1998; 28: 1191-8. [ Links ]

3. Saint-Marc Girardin MF, Zafrani ES, Prigent A, et al. Unilobar small hepatic vein obstruction: possible role of progestogen given as oral contraceptive. Gastroenterology 1983; 84: 630-5. [ Links ]

4. Langlet P, Valla D. Is surgical portosystemic shunt the treatment of choice in Budd-Chiari syndrome? Acta Gastroenterol Belg 2002; 65: 155-60. [ Links ]

5. Navarro F, Le Moine MC, Fabre JM, et al. Specific vascular complications of orthotopic liver transplantation with preservation of the retrohepatic vena cava: review of 1361 cases. Transplantation 1999; 68: 646-50. [ Links ]

6. Parrilla P, Sánchez-Bueno F, Figueras J, et al. Analysis of the complications of the piggy-back technique in 1,112 liver transplants. Transplantation 1999; 67: 1214-7. [ Links ]

7. Wang SL, Sze DY, Busque S, et al. Treatment of hepatic venous outflow obstruction after piggyback liver transplantation. Radiology 2005; 236: 352-9. [ Links ]

8. Chung RT, Iafrate AJ, Amrein PC, Sahani DV, Misdraji J. Case records of the Massachusetts general hospital. Case 15-2006. A 46-year-old woman with sudden onset of abdominal distention. N Engl J Med 2006; 354: 2166-75. [ Links ]

9. Kew MC, Hodkinson HJ. Membranous obstruction of the inferior vena cava and its causal relation to hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int 2006; 26: 1-7. [ Links ]

10. Valla DC. The diagnosis and management of the Budd-Chiari syndrome: consensus and controversies. Hepatology 2003; 38: 793-803. [ Links ]

11. Senzolo M, Cholongitas EC, Patch D, Burroughs AK. Update on the classification, assessment of prognosis and therapy of Budd-Chiari syndrome. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005; 2: 182-90. [ Links ]

12. Menon KV, Shah V, Kamath PS. The Budd-Chiari syndrome. N Engl J Med 2004; 350: 578-85. [ Links ]

13. Dilawari JB, Bambery P, Chawla Y, et al. Hepatic outflow obstruction (Budd-Chiari syndrome). Experience with 177 patients and a review of the literature. Medicine 1994; 73: 21-36. [ Links ]

14. Maddrey, WC. Hepatic vein thrombosis (Budd-Chiari syndrome). Hepatology 1984; 4: 44S-46S. [ Links ]

15. Hirshberg, B, Shouval, D, Fibach, E, et al. Flow cytometric analysis of autonomous growth of erythroid precursors in liquid culture detects occult polycythemia vera in the Budd-Chiari syndrome. J Hepatol 2000; 32: 574-8. [ Links ]

16. Primignani M, Barosi G, Bergamaschi G, et al. Role of the JAK2 mutation in the diagnosis of chronic myeloproliferative disorders in splanchnic vein thrombosis. Hepatology 2006; 44: 1528-34. [ Links ]

17. Mitchell, MC, Boitnott, JK, Kaufman, S, et al. Budd-Chiari syndrome: etiology, diagnosis and management. Medicine (Baltimore) 1982; 61: 199-218. [ Links ]

18. Valla, D, Le, MG, Poynard, T, et al. Risk of hepatic vein thrombosis in relation to recent use of oral contraceptives: a case-control study. Gastroenterology 1986; 90: 807-11. [ Links ]

19. Khuroo MS, Dutta DV. Budd-Chiari syndrome following pregnancy: report of 16 cases, with roentgenologic, hemodynamic and histologic studies of the hepatic outflow tract. Am J Med 1980; 68: 113-21. [ Links ]

20. Mahmoud AE, Elias E, Beauchamp N, Wilde JT. Prevalence of the factor V Leiden mutation in hepatic and portal vein thrombosis. Gut 1997; 40: 798-800. [ Links ]

21. Laposata M. The prothrombin G2021A mutation: a new high-prevalence congenital risk factor for thrombosis. Gastroenterology 1999; 116: 213-5. [ Links ]

22. Bayraktar Y, Balkanci F, Bayraktar M, et al. Budd-Chiari syndrome: a common complication of Behcet's disease. Am J Gastroenterol 1997; 92: 858-62. [ Links ]

23. Rector WG, Xu Y, Goldstein L, et al. Membranous obstruction of the inferior vena cava in the United States. Medicine 1985; 64: 134-43. [ Links ]

24. Repiso A, Alcántara M, Muñoz-Rosas C, et al. Extraintestinal manifestations of Crohn's disease: prevalence and related factors. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2006; 98: 510-7. [ Links ]

25. Bolondi L, Gaiani S, Li Bassi S, et al. Diagnosis of Budd-Chiari syndrome by pulsed Doppler ultrasound. Gastroenterology 1991; 100 (Pt 1): 1324-31. [ Links ]

26. Noone TC, Semelka RC, Siegelman ES, et al. Budd-Chiari syndrome: spectrum of appearances of acute, subacute, and chronic disease with magnetic resonance imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging 2000; 11: 44-50. [ Links ]

27. Olliff SP. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in the management of Budd Chiari syndrome. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006; 18: 1151-4. [ Links ]

28. Socha P, Ryzko J, Janczyk W, et al. Hepatic vein thrombosis as a complication of ulcerative colitis in a 12-year-old patient. Dig Dis Sci 2007; 52: 1293-8. [ Links ]

29. Guglielmi A, Fior F, Halmos O, Veraldi GF, Rossaro L. Transhepatic fibrinolysis of mesenteric and portal vein thrombosis in a patient with ulcerative colitis: a case report. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11: 2035-8. [ Links ]

30. Zimmerman MA, Cameron AM, Ghobrial RM. Budd-Chiari syndrome. Clin Liver Dis 2006; 10: 259-73. [ Links ]

31. Klein AS. Management of Budd-Chiari syndrome. Liver Transpl 2006; 12(Supl. 2): S23-S28. [ Links ]

32. Eapen CE, Velissaris D, Heydtmann M, Gunson B, Olliff S, Elias E. Favourable medium term outcome following hepatic vein recanalisation and/or transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for Budd Chiari syndrome. Gut 2006; 55: 878-84. [ Links ]

33. Langlet P, Escolano S, Valla D, et al. Clinicopathological forms and prognostic index in Budd-Chiari syndrome. J Hepatol 2003; 39: 496-501. [ Links ]

34. Chasan-Taber L, Stampfer MJ. Epidemiology of oral contraceptives and cardiovascular disease. Ann Intern Med 1998; 128: 467-77. [ Links ]

35. Rosenberg L, Palmer JR, Rao RS, Shapiro S. Low-dose oral contraceptive use and the risk of myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med 2001; 161: 1065-70. [ Links ]

36. Gomes MP, Deitcher SR. Risk of venous thromboembolic disease associated with hormonal contraceptives and hormone replacement therapy: a clinical review. Arch Intern Med 2004; 164: 1965-76. [ Links ]

37. Spitzer WO, Lewis MA, Heinemann LAJ, et al. Third generation oral contraceptives and risk of venous thromboembolic disorders: an international case-control study. BMJ 1996; 312: 83-8. [ Links ]

38. WHO. Effect of different progestagens in low oestrogen oral contraceptives on venous thromboembolic disease. World Health Organization Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease and Steroid Hormone Contraception. Lancet 1995; 346: 1582. [ Links ]

39. Rahhal RM, Pashankar DS, Bishop WP. Ulcerative colitis complicated by ischemic colitis and Budd Chiari syndrome. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2005; 40: 94-7. [ Links ]

40. Valla DC. Hepatic vein thrombosis (Budd-Chiari syndrome). Semin Liver Dis 2002; 22: 5-14. [ Links ]

41. Chesner IM, Muller S, Newman J. Ulcerative colitis complicated by Budd-Chiari syndrome. Gut 1986; 27: 1096-100. [ Links ]

42. Lam A, Borde I, et al. Coagulation studies in ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 1975; 68: 245-8. [ Links ]

43. Maccini D, Berg J, Bell G. Budd-Chiari syndrome and Crohn's disease: an unreported association. Dig Dis Sci 1989; 34: 1933-6. [ Links ]

44. Lashner BA, Kane SV, Hanauer SB. Lack of association between oral contraceptive use and ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 1990; 99: 1032-6. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Mariano Valdés Mas.

Avda. Alfonso X el Sabio, 3, 2. 30008 Murcia, Spain.

e-mail: marianovaldesmas@yahoo.es

Received: 24-01-09.

Acceptad: 04-02-09.

texto en

texto en