Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

versión impresa ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.104 no.7 Madrid jul. 2012

https://dx.doi.org/10.4321/S1130-01082012000700001

EDITORIAL

Endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy dilation

Dilatación de la esfinterotomía biliar endoscópica

Jesús García-Cano

Department of Digestive Diseases. Hospital Virgen de la Luz. Cuenca, Spain

The year 2013 will mark the 40th anniversary of the introduction of endoscopic biliary sphincteroromy (EBS) in the therapeutic armamentarium for the treatment of common bile duct obstruction. Early EBS procedures were performed for the removal of common bile duct stones, which still is a primary indication. EBS was the first therapeutic step for endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography (ERCP), which was first carried out for diagnostic purposes 1968.

On August 19, 1974 Professor Kawai, one of the pioneers of EBS, reported his initial experience at Centro Médico Nacional de México during the 3rd International Congress of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. The innovation was welcomed as an extraordinary achievement and all attendants applauded what was deemed to become a major milestone for therapeutic digestive endoscopy (1). The sphincterotome likely represents the device with the best cost-benefit ratio for the endoscopic treatment of digestive diseases.

Intially, following EBS, stones were usually left within the common bile duct to allow for their spontaneous expulsion. Complications such as cholangitis led to the use of Fogarty-type balloon catheters and Dormia baskets for their extraction during ERCP.

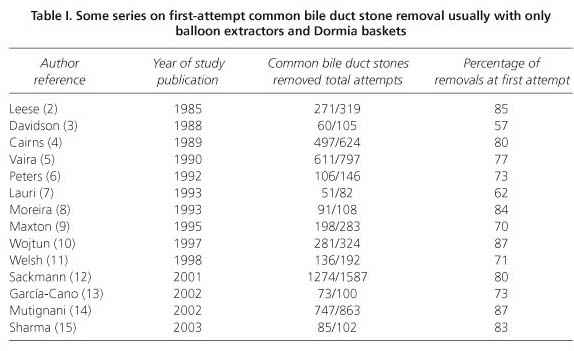

It was soon observed that 100% of common bile duct stones could not be removed with a single ERCP-EBS procedure using only these balloons and baskets (Table I). Failure was usually associated with disparity between stone size and sphincterotomy size, which commonly cannot exceed 15 mm. Various factors may influence a sphincterotomy's smaller size, including a juxtadiverticular papilla of Vater and coagulation disorders.

Retained choledocholithiasis following a first ERCP imply new endoscopy sessions, various lithotrypsy procedures (both intra- and extra-choledochal), patient referral for surgery, or a palliative strategy such as biliary stent (13).

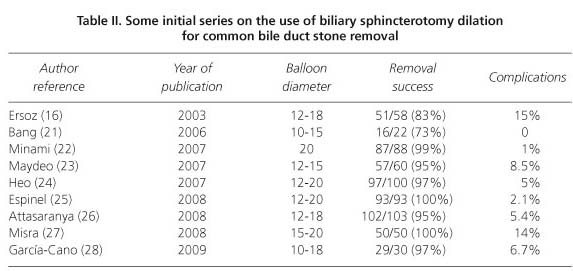

In 2003 Ersoz (16) first reported on biliary sphincterotomy dilation (EBSD) using big-sized hydrostatic balloons (12-20 mm in diameter) as a technique to remove challenging common bile duct stones.

Staritz, in 1982 (17), had previously published his experience with papilla of Vater dilation using an 8-mm balloon. This dilation was carried out with no prior section of the sphincter of Oddi, and was proposed as an alternative to common bile duct stones extraction with EBS. The procedure became widespread during the 1990's. The primary idea was to preserve sphincter function, particularly in younger patients. However, several deaths from serious pancreatitis secondary to papillary dilation in the absence of sphincterotomy were reported (18). We had a similar case ourselves (19).

The results of sphincteroplasty without prior EBS differ between eastern and western countries. For poorly understood reasons, series reported in countries such as Japan and Korea have a very low rate of pancreatitis following papillary dilation without EBS. While this type of sphincteroplasty is uncommon in Europe and the USA, a recent paper by Chan et al. (20), where the papilla was dilated using large-diameter balloons (over 10 mm) during not only 1 but rather up to 6 minutes, highlights that pancreatitis rates may be lower because such forcible, prolonged dilation disrupts sphincter of Oddi fibers similarly to EBS but with fewer complications.

Anyway, EBSD is seemingly a procedure unlike papillary dilation with no prior incision. As the biliary and pancreatic orifices are moved apart by EBS, the expansive force exerted by the inflated balloon might act on the choledochus rather than the duct of Wirsung, which would render the incidence and severity of acute pancreatitis a seemingly non-significant complication following EBSD.

The use of EBSD has become rapidly widespread, and numerous series have been reported on its efficacy and safety (Table II). Its impact is such that it may be considered a new milestone similarly to EBS or biliary drainage prostheses.

This issue of Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas includes a paper by Martín Arranz et al. (28) that again highlights the fact that EBSD offers an excellent success rate in the removal of challenging common bile duct stones with a reduced index of complications. The study was performed at Hospital La Paz, Madrid, one of the big pioneering centers within the Spanish National Health system. With a high number of patients (109) who underwent 120 EBSD procedures, the rate of complete common bile duct clearance following a first ERCP-EBS-EBSD was 91%, and 96.7% after a second ERCP-EBSD. Bleeding was the commonest complication. This paper confirms that, overall, EBSD is the easiest, safest way of treating challenging common bile stones in the choledochus.

The low rate of pancreatitis after papillary dilation with diameters (e.g., 20 mm) that at times may engender some distrust when used in other anatomical locations, such as the esophagus, was surprising from the very start. However, as with other therapy techniques, complications increase with procedure numbers. Hemorrhage, occasionally severe, seems to be most common (29,30).

Complications seem to be similar when EBSD is performed during the first ERCP-EBS and when initial sphincterotomy is allowed time to heal and dilation takes place in a second session.

Dilation balloon diameter must be adjusted to that of the suprapapillary distal choled-ochus. Excessive dilation may cause perforation (31). Dilation to 15 mm is most common and is maybe the safest approach if in doubt. The distal choledochus may also be dilated during the first ERCP using plastic prostheses or, in selected patients, removable metallic ones (32), only to attempt EBSD and stone removal again after a few weeks.

The guidewire on which the dilator balloon slides must be properly lodged within the intrahepatic bile ducts to ensure it is away from the cystic duct, which may become perforated during dilation.

Many endoscopists use short guidewires (about 260 cm) for ERCP. To maintain biliary cannulation following dilation longer guidewires (about 460 cm) are usually needed. These products' manufacturers are expected to condition dilation balloons for shorter guidewires, for instance by placing an orifice near the balloon through which the guidewire may be slid, as in other instruments allowing exchange with shorter guides.

The dilation balloon must be theoretically placed with its middle portion within the papilla. Upon inflation it may fully slide towards the choledochus or fall out into the duodenum. Initial inflation to half the pressure required for a given diameter, followed by full inflation once the balloon is properly placed, usually ensures success.

The present study by Martín Arranz et al. (28) adds to the increasing scientific understanding that EBSD is an excellent technique for the extraction of big or multiple common bile duct stones in the presence of anatomical challenges (juxtadiverticular papilla, tapering distal choledochus,...), coagulation disorders, or prior surgery (Billroth II gastrectomy). In addition, it is a safe technique that will not increase ERCP-EBS-related complications.

References

1. Vázquez-Iglesias JL. Esfinterotomía endoscópica. En: Vázquez-Iglesias JL, editor. Endoscopia digestiva alta.II Terapéutica. La Coruña: Galicia Editorial S.A.; 1995. p. 165-95. [ Links ]

2. Leese T, Neoptolemos P, Carr-Locke DL. Successes, failures, early complications and their management following endoscopic sphincterotomy: results in 394 consecutive patients from a single centre. Br J Surg 1985;72:215-9. [ Links ]

3. Davidson BR, Neoptolemos JP, Carr-Locke DL. Endoscopic sphincterotomy for common bile duct calculi in patients with gall bladder in situ considered unfit for surgery. Gut 1988;29:114-20. [ Links ]

4. Cairns SR, Dias L, Cotton PB, Salmon PR, Russel RCG. Additional endoscopic procedures instead of urgent surgery for retained common bile duct stones. Gut 1989; 30:535-540. [ Links ]

5. Vaira D, D'Anna L, Ainley C, Dowsett J, Williams S, Baillie J, et al. Endoscopic sphincterotomy in 1000 consecutive patients. Lancet 1989;2:431-3. [ Links ]

6. Peters R, Macmathuna P, Lombard M, Karani J, Westaby D. Management of common bile duct stones with a biliary endoprosthesis. Report on 40 cases. Gut 1992;33:1412-5. [ Links ]

7. Lauri A, Horton RC, Davidson BR, Burroughs AK, Dooley JS. Endoscopic extraction of bile duct stones: management related to stone size. Gut 1993;34:1718-21. [ Links ]

8. Moreira V, Meroño E, Martín-de-Argila C, San Román AL, Gisbert J, González A, et al. Postcholecistectomy choledocholithiasis: real efficacy of endoscopic sphincterotomy? Rev Esp Enferm Dig 1993;83:439-45. [ Links ]

9. Maxton DG, Tweedle DEF, Martin DF. Retained common bile duct stones after endoscopic sphincterotomy: temporary and longterm treatment with biliary stenting. Gut 1995;36:446-9. [ Links ]

10. Wojtun S, Gil J, Gietka W, Gil M. Endoscopic sphincterotomy for choledocholithiasis: A prospective single-center study on the short-term and long-term treatment results in 483 patients. Endoscopy 1997;29:258-65. [ Links ]

11. Welsh FKS, Mudan SS, Knight MJ. Single-centre audit of endoscopic common bile duct stone retrieval. Br J Surg 1988;86:423. [ Links ]

12. Sackmann M, Holl J, Sauter GH, Pauletzki J, von Ritter C, Paumgartner G. Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy for clearance of bile duct stones resistant to endoscopic extraction. Gastrointest Endosc 2001;53:27-32. [ Links ]

13. García-Cano Lizcano J, González Martín JA, Pérez Sola A, Morillas Ariño MJ. Success rate of complete extraction of common bile duct stones at first endoscopy attempt. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2002;94:346-50. [ Links ]

14. Mutignani M, Shah SK, Foschia F, Pandolfi M, Perri V, Costamagna G. Transnasal extraction of residual biliary stones by Seldinger technique and nasobiliary drain. Gastrointest Endosc 2002;56:233-8. [ Links ]

15. Sharma SK, Larson KA, Adler Z, Goldfarb MA. Role of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in the management of suspected choledocholithiasis. Surg End 2003;17:868-71. [ Links ]

16. Ersoz G, Tekesin O, Ozutemiz AO, Gunsar F. Biliary sphincterotomy plus dilation with a large balloon for bile duct stones that are difficult to extract. Gastrointest Endosc 2003;57:156-9. [ Links ]

17. Staritz M, Ewe K, Meyer zum Büschenfelde KH. Endoscopic papillary dilatation: an alternative to papillotomy? (Article in German, author's transl). Dtsch Med Wochenschr 1982;107:895-7. [ Links ]

18. Disario JA, Freeman ML, Bjorkman DJ, Macmathuna P, Petersen BT, Jaffe PE, et al. Endoscopic balloon dilation compared with sphincterotomy for extraction of bile duct stones. Gastroenterology 2004;127:1291-9. [ Links ]

19. García-Cano J. Fatal pancreatitis after endoscopic balloon dilation for extraction of common bile duct stones in an 80-year-old woman. Endoscopy 2006;38:431. [ Links ]

20. Chan HH, Lai KH, Lin CK, Tsai WL, Wang EM, Hsu PI, et al. Endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation alone without sphincterotomy for the treatment of large common bile duct stones. BMC Gastroenterol 2011;11:69. [ Links ]

21. Bang S, Kim MH, Park JY, Park SW, Song SY, Chung JB. Endoscopic papillary balloon dilation with large balloon after limited sphincterotomy for retrieval of choledocholithiasis. Yonsei Med J 2006;47:805-10. [ Links ]

22. Maydeo A, Bhandari S. Balloon sphincteroplasty for removing difficult bile duct stones. Endoscopy 2007; 11:958-61. [ Links ]

23. Heo JH, Kang DH, Jung HJ, Kwon DS, An JK, Kim BS, et al. Endoscopic sphincterotomy plus large-balloon dilation versus endoscopic sphincterotomy for removal of bile-duct stones. Gastrointest Endosc 2007;66:720-6. [ Links ]

24. Espinel J, Pinedo E. Large balloon dilation for removal of bile duct stones. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2008;100:632-6. [ Links ]

25. Attasaranya S, Cheon YK, Vittal H, Howell DA, Wakelin DE, Cunningham JT, et al. Large-diameter biliary orifice balloon dilation to aid in endoscopic bile duct stone removal: a multicenter series. Gastrointest Endosc 2008;67:1046-52. [ Links ]

26. Misra SP, Dwivedi M. Large-diameter balloon dilation after endoscopic sphincterotomy for removal of difficult bile duct stones. Endoscopy 2008;40:209-13. [ Links ]

27. García-Cano J, Taberna-Arana L, Jimeno-Ayllón C, Chicano MV, Fernández RM, Sánchez LS, et al. Biliary sphincterotomy dilation for the extraction of difficult common bile duct stones. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2009;101:541-5. [ Links ]

28. Martín-Arranz E, Rey-Sanz R, Martín-Arranz MD, Gea-Rodríguez F, Mora-Sanz P, Segura-Cabral JM. Safety and efficacy of large balloon sphincteroplasty in a third care hospital. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2012;104(7):355-9. [ Links ]

29. Lee TH, Park SH, Lee CK, Chung IK, Kim SJ, Kang CH. Life-threatening hemorrhage following large-balloon endoscopic papillary dilation successfully treated with angiographic embolization. Endoscopy 2009;41(Supl. 2):E241-2. [ Links ]

30. García-Cano Lizcano J, Delgado Torres V, Garrido Espada N, Amao Ruiz EJ. Tratamiento de la hemorragia incoercible tras esfinterotomía biliar endoscópica con la infusión de factor VII recombinante. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2012;104(Supl. I):159. [ Links ]

31. Lee YS, Moon JH, Ko BM, Choi HJ, Cho YD, Park SH, et al. Endoscopic closure of a distal common bile duct perforation caused by papillary dilation with a large-diameter balloon (with video). Gastrointest Endosc 2010;72:616-8. [ Links ]

32. García-Cano J, Garrido Espada N, Martínez Fernández R, Serrano Sánchez L, Reyes Guevara AK, Gimeno Ayllón C, et al. Utilización de prótesis metálicas recubiertas en coledocolitiasis difíciles de extraer por CPRE. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2011;103(Supl. I):108. [ Links ]

texto en

texto en