Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

versión impresa ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.105 no.10 Madrid nov./dic. 2013

https://dx.doi.org/10.4321/S1130-01082013001000004

ORIGINAL PAPERS

Double-balloon enteroscopy in the management of patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: A retrospective cohort multicenter study

Enteroscopia de doble balón en el tratamiento de paciente con síndrome de Peutz-Jeghers: un estudio multicéntrico de cohorte retrospectiva

Miguel Serrano1, Susana Mão-de-Ferro1, Rolando Pinho2,3, Ricardo Marcos-Pinto4,5, Pedro Figueiredo6,7, Sara Ferreira1,8, Isabel Claro1,8, Miguel Mascarenhas-Saraiva2,3 and António Dias-Pereira1

1Serviço de Gastrenterologia. Instituto Português de Oncologia de Lisboa Francisco Gentil (IPOLFG), E.P.E. Lisboa, Portugal.

2ManopH - Laboratório de Endoscopia e Motilidade Digestiva. Porto, Portugal.

3ManopH - Instituto CUF. Porto, Portugal.

4Serviço de Gastrenterologia. Hospital Geral de Santo António (HGSA), E.P.E. Porto, Portugal.

5Instituto de Ciências Biomédicas Abel Salazar. Universidade do Porto. Porto, Portugal.

6Serviço de Gastrenterologia. Centro Hospitalar e Universitário de Coimbra (HUC). Coimbra, Portugal.

7Faculdade de Medicina. Universidade de Coimbra. Coimbra, Portugal.

8Clínica de Risco Familiar. Instituto Português de Oncologia de Lisboa Francisco Gentil, E.P.E. Lisboa, Portugal

ABSTRACT

Background and objective: Little is known about the clinical impact of double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE) in patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS).

The aim of this study was to assess the efficacy and safety of DBE in the management of small-bowel polyps in PJS patients.

Patients and methods: We conducted a multicentre, retrospective cohort study, which included all consecutive patients diagnosed with PJS who underwent DBE for polypectomy between January 2006 and August 2012. In all cases, previous videocapsule enteroscopy had shown at least one polyp ≥ 10 mm in size.

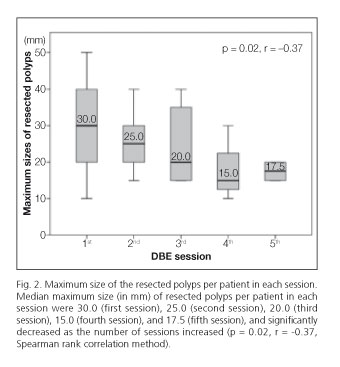

Results: Twenty-five patients (13 men; median age 36 years; 14 with prior laparotomy) underwent 46 DBE procedures (1 to 5 per patient, 44 via oral route). Polypectomy was performed in 39/46 DBEs. A total of 214 polyps were removed (median-size 30 mm), with a median number of polypectomies per procedure of 5.0 (range 1-18). The estimated maximum-sizes of resected polyps significantly decreased at each session: 30.0, 25.0, 20.0, 15.0, and 17.5 mm (p = 0.02). In 7 DBEs no polypectomy was performed (4-only minor polyps detected; 3-endoscopic irresecability). Complications occurred in 3/39 of therapeutic procedures (2-minor delayed bleeding; 1-mucosal tear), all of them dealt with conservative or endoscopic therapy. Six patients underwent elective surgery post DBE due to polyps not amenable for endoscopic resection. There were no small-bowel polyp related complications during a median follow-up of 56.5 months.

Conclusion: DBE showed to be a safe and effective technique in the management of small-bowel polyps in PJS patients, allowing a presymptomatic and non-surgical approach.

Key words: Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Double balloon enteroscopy. Small-bowel polyps. Hamartomatous polyposis. Deep small-bowel enteroscopy. Balloon-assisted enteroscopy.

Introduction

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS) is an autosomal dominant hereditary disease caused by a germline mutation in the STK11 (LKB1) gene, located on chromosome 19p13.3 (1). A pathogenic mutation in the STK11 gene is found in 80 to 94 percent of clinically affected patients (2,3). The incidence of this condition is estimated to be between 1 in 50,000 to 1 in 200,000 live births (4). PJS is characterized by the presence of numerous pigmented spots on the lips and the buccal mucosa and multiple gastrointestinal hamartomatous polyps. Hamartomas occur most commonly in the small intestine (65 to 95 percent), predominantly in the jejunum (5,6). Gastrointestinal polyps may cause gastrointestinal bleeding, anemia and abdominal pain due to intussusception, obstruction or infarction (5,7). Half of patients with PJS experience symptoms before 20 years of age, mainly due to obstruction and intussusception, leading to multiple laparotomies with intestinal resection that can ultimately result in short-bowel syndrome and/or severe adhesions (5,8).

In addition, patients with PJS carry a significantly increased risk for the development of gastrointestinal and non-gastrointestinal malignancies, with relative risks ranging from 10 to 18 in comparison with the general population (9,10).

Because of the risk of complications related to polyps and the risk of malignancy, screening is recommended for individuals with clinical features of PJS (11). The main indication for surveillance of the small-bowel is the prevention of intussusception and the need for emergency laparotomy. Current consensus recommendations are that small-bowel surveillance using video capsule endoscopy (VCE) should be performed every 3 years if polyps are found at the initial examination, from age 8 years, or earlier if the patient is symptomatic; if few or no polyps are found at the initial examination, screening should commence again at the age of 18 (11).

Double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE) was first introduced by Yamamoto et al. in 2001, and has rapidly become an established and invaluable tool for diagnosing and treating small-bowel diseases (12). The major advantage of DBE compared with VCE and radiologic methods to visualize the small-bowel is the ability to perform a wide variety of therapeutic interventions during the same procedure (13). Until a couple of years ago, little was known about the clinical impact of surveillance and treatment of small-bowel polyps by using DBE in PJS patients (14). Since then, some studies have described a high diagnostic yield of DBE in PJS patients with successful polypectomy which, in theory, might prevent intussusceptions and avoid the need for emergency surgery (15-18).

The aim of this retrospective cohort study was to evaluate the therapeutic efficacy, clinical impact, and safety of endoscopic management of small-bowel polyps in patients with PJS by using DBE.

Patients and methods

Study design ant setting

We conducted a retrospective cohort study which included all consecutive patients with PJS from four tertiary-care referral centres (IPOLFG, HGSA, ManopH and HUC) who had undergone DBE for polypectomy between January 2006 and August 2012.

The study was approved by the institutional review board.

Patients

This study included patients diagnosed with PJS on the basis of either the diagnostic criteria defined by the World Health Organization (19) or a proven STK11 mutation with a previous VCE showing at least one small-bowel polyp ≥ 10 mm in size, referred for DBE.

Patients' information and follow-up were obtained by chart review.

Enteroscopic procedure and therapy

DBE procedures were performed with the Fujinon EN-450T5 or EN-450P5 enteroscopes (Fujinon Inc., Saitama, Japan) under deep sedation with propofol (administered by an anaesthesiologist) and on an outpatient basis.

The insertion route was determined by the findings of VCE. An anterograde approach was used for lesions noted in the first 60 % of a VCE study (based on the time at which the lesion was noted in the small-bowel relative to the total small-bowel transit time), whereas a retrograde approach was used for lesions in the distal 40 %. The investigation was performed after overnight fasting in oral procedures, or after bowel preparation using standard colonoscopy preparation in retrograde procedures.

For defining the insertion depth, the small-bowel was divided into 6 segments (proximal, mid and distal jejunum and proximal, mid and distal ileum) according to the accumulation of net advancement of each push-and-pull maneuver. To confirm total enteroscopy, we used Indian ink tattooing of the small-bowel. Total enteroscopy also was confirmed in the case of reaching the cecum by an oral approach.

At DBE, the polyp size was estimated according to the width of the biopsy forceps or the diameter of the polypectomy snare. Small-bowel polyps with a diameter of ≥ 10 mm were considered suitable for polypectomy. Polypectomy was performed with commercially available oval snares (up to 45 mm in diameter). In some cases a 0.9 % isotonic saline solution was injected into the submucosal layer at the endoscopist discretion before polypectomy. Polyps that were deemed not suitable for safe endoscopic resection were referred for surgery. In those cases, Indian ink tattooing of the small-bowel was used to ease recognition upon laparotomy. Polyps were not routinely retrieved for pathological examination, considering the low risk of malignancy of PJS polyps.

In cases in which not all polyps larger than 10 mm were removed, DBE was repeated within 6-9 months after the index procedure. Surveillance with VCE, every 2-3 years, was carried out after all large polyps were resected. If polyps > 10 mm in size were detected during surveillance, DBE was scheduled. DBE findings (size, number and location of polyps, and polypectomy) were retrieved from the endoscopy report.

DBE-induced complications were evaluated through the review of patient medical chart and DBE report. A complication was defined as any event that changed the health status of a patient negatively, and that occurred during the 30-day period after DBE. Complications were further classified as intraprocedural, early (≤ 24 hours), or delayed (2-30 days). Therapeutic interventions taken with regard to complications were reported as conservative, endoscopic or surgical.

The setting (emergent vs. elective) and need for further therapeutic intervention [laparotomy ± intraoperative enteroscopy (IOE)] during follow-up after DBE were recorded.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for the patients' data and DBE parameters, and are presented as medians, means, and SD, as well as ranges (minimum-maximum) for continuous data, and as absolute and relative frequencies for categorical data. Correlations between the median number and size of resected polyps and DBE sessions were performed by using the Spearman rank correlation method.

All p values were 2-sided. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data handling and statistical analysis were performed with SPSS software package version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Patient characteristics

Between January 2006 and August 2012, 25 patients with PJS were included in the study [13 men; median age 36.0 years (range 17-73 years)]. Fourteen patients had a history of laparotomy, including 11 patients with enterectomy for complicated small-bowel polyps (intussusception in 85.7 %). Clinical characteristics are presented in table I.

Procedural parameters and polypectomy

In total, 46 DBE procedures were performed in these patients during the analysed period. Procedural parameters are summarized in table II. The mean number of DBEs per patient was 1.8 ± 2.0 (range 1-5). Forty-four DBE were preformed via an oral approach and 2 through an anal approach. Twenty-five of these procedures were index DBE procedures (23 - oral route; 2 - anal route), and twenty-one were repeated DBE procedures (all through the oral route). The indications for repeated DBE were scheduled polypectomy after the detection of polyps larger than 10 mm on surveillance VCE (12 procedures, 57.1 %) and resection of known polyps left in situ at the index procedure (9 procedures, 42.9 %). The mean procedure duration was 84.3 ± 29.5 minutes (range 45-150). Insertion depths are depicted in table II.

Endoscopic resection of small-bowel polyps was performed in 39 DBE procedures (84.8 %). In six patients polyps were not resected during the index DBE because they were either too large for endoscopic removal (3 cases) or because only minor polyps were found (3 cases) despite deep insertion (proximal ileum). No polypectomy was carried out in one of the repeated DBE procedures (diminutive polyps). A total of 214 small-bowel polyps were resected, with an estimated median diameter of 30.0 mm (range 10-50). The median number of resected polyps per exam was 5.0 (range 1-18) (Table II).

The median number of resected polyps per patient increased from 3.0 (index DBE) to 5.0 (2nd session), 7.0 (3rd session), 6.0 (4th session) and 4.0 (5th session) as the number of sessions increased, although not to a significant extent (p = 0.17, r = 0.22) (Fig. 1).

The estimated median maximum sizes of resected polyps were 30.0, 25.0, 20.0, 15.0, and 17.5 mm at sessions 1 through 5, respectively, and significantly decreased as the number of sessions increased (p = 0.02, r = -0.37) (Fig. 2).

Six patients were referred for elective surgical resection (all after the index procedure). The indications for enterectomy were the presence of a jejunal neoplasia (1 case), polyps locally concentrated in large numbers (2 cases), bulky polyps (2 cases; size up to 60 mm) (Fig. 3) and invaginated polyp (1 case). Surgical specimens were consistent with hamartomas and the jejunal neoplasia harboured a small-bowel adenocarcinoma (pT2 N0).

Complications

We registered a total of 3 complications among all of the DBE procedures (6.5 %). The complications involved one small-bowel mucosal tear and two gastrointestinal bleedings. All complications occurred in patients who underwent therapeutic DBE (7.3 %). No post-polypectomy perforations were reported.

The mucosal tear was detected during the procedure at an enteric anastomosis in a patient with history of small-bowel resections. Despite there were no signs of perforation the tear was closed with the placement of endoclips.

Two delayed postpolypectomy bleeds were reported, accounting for an overall postpolypectomy bleeding rate per polyp, per procedure, and per patient of 0.9 %, 4.3 %, and 8.0 %, respectively. Both were categorized as minor (melena and haemoglobin drop < 2.0 g/dL from baseline) and were managed with conservative care (outpatient clinical observation with no need of blood replacement).

Follow-up

The median follow-up time after the index DBE was 56.5 months (range 3-76 months), with a total of 1,129 person-months. During that period, one patient, with a history of repeated small-bowel resections, presented with acute small-bowel obstruction because of adhesions, which were found and treated during laparotomy. There were no reports of complications caused by small-bowel polyps during follow-up.

Discussion

The distribution of PJS polyps throughout the GI tract makes surveillance and treatment challenging, particularly for polyps located within the small-bowel. The initial main purpose of regular surveillance is the prevention of small bowel obstruction and intussusception by removal of hamartomas of significant size (11).

Until only a few years ago, push enteroscopy (for proximal lesions), primary surgical resection and IOE with polypectomy were the only available means for treating polyps in the small intestine in these patients. In the last decade, development of DBE and VCE has allowed direct visualisation of the small bowel, and in the case of DBE, resection of polyps via a standard snare polypectomy without the need for laparotomy (13).

Ohmiya et al. were the first to describe the use of DBE for the diagnosis and treatment of Peutz-Jeghers polyps in the small intestine (14). In two patients, multiple polyps (10-60 mm) were detected in the jejunum and ileum and resected without subsequent bleeding or perforation. Since then, a few studies have reported the clinical applicability of DBE in PJS patients (15-18).

In the present study, we sought to evaluate the therapeutic efficacy, clinical impact, and safety of DBE polypectomy in 25 patients with PJS with known significant small-bowel polyps according to findings in VCE. Unlike two former studies (15,16), where DBE was used as a diagnostic and therapeutic tool, the centers participating in this study favor a step-up approach for surveillance, making complementary use of the different techniques. As a first step we use VCE because it is a safe, non-invasive and sensitive method for visualization of the small-bowel lumen and the detection of polyps. If polyps with a diameter larger than 10 are found, DBE with polypectomy is performed as the second step. The adoption of this strategy identified small-bowel polyps, predominantly in the jejunum, in all patients, and led to therapeutic intervention in 85 % of procedures (19 out of 25 patients). Nevertheless, in 3 patients only small hamartomas where found during DBE, underscoring the limitations of VCE in estimating polyp size as previously stated (20,21).

Ideally, DBE polypectomy should be performed when polyps are relatively small, thereby avoiding the technically more difficult endoscopic resection of large polyps at a later stage. Despite the high therapeutic performance reported in the study, six patients were still referred for elective primary or adjuvant surgical resection (2 with IOE) due to the presence of large polyps that could not be safely removed endoscopically. Our high surgical referral rate in comparison with results previously reported (15,16), in which only one out of 28 patients was referred for elective laparotomy, outlines some limitations of DBE when dealing with polyps that are bulky, locally concentrated in large numbers, invaginated and thick-stalked, and those with serosal retraction into the stalk. Mathus-Vliegen and Tytgat (22) had already noted, back in 1986 when performing IOE, that under these circumstances polyps were unsuitable for polypectomy even if performed during surgery, and recommended that such lesions be removed by enterectomy.

Two studies have reported that the total enteroscopy rate and maximum insertion depth at DBE was significantly lower in patients with PJS and a history of laparotomies than in those without previous laparotomies (16,17). In the present study, total enteroscopy was achieved in only one patient, but this fact did not hampered therapeutic performance or resulted in a complicated disease course. Therefore, it seems that history of abdominal surgery does not preclude the efficacy of DBE in patients with this condition.

Another major issue is the complications of DBE. The complication rate in patients with PJS who underwent therapeutic DBE (7.3 %) was slightly higher than that previously reported by Sakamoto et al. (6.8 %) (16) and Mensink et al. (4.3 %) (23). Nevertheless, all of our complications were minor and managed in a non-invasive manner, suggesting that DBE polypectomy is a relatively safe technique. One important fact is that during the reviewed period no perforation occurred, opposing the report of the German DBE Study Group, in which the perforation rate was 1.5 % per resected polyp (24). This finding might be related to careful selection of polyps to be endoscopically resected.

PJS patients carry a high cumulative intussusception risk at young age (50?% at the age of 20 years) (8). Intussusceptions are generally caused by polyps larger than 15 mm (with polyp size probably being the most important risk factor for small-bowel intussusception), present predominantly as an acute abdomen and lead to surgical emergencies (8). These findings support the rationale of enteroscopic surveillance to prevent complications. This study showed that, after a median follow-up of 56.5 months, timely endoscopic management with removal of small-bowel hamartomas ≥ 10 mm in diameter was useful for preventing intussusceptions, and avoiding emergency laparotomy. This trend was probably related to a significant reduction in size of resected polyps as the number of sessions increased. In fact, the adoption of this strategy, might eventually lead to the elimination of significant polyps, thereby precluding complications and associated morbidity and mortality.

Another indication for surveillance in older patients with PJS is the elevated risk of small-bowel cancer (11). The mechanism of carcinogenesis in PJS and the role of the PJS polyp remain controversial. Some authors propose an unique hamartoma-adenoma-carcinoma pathway (25). This hypothesis is supported by the finding of adenomatous foci within PJS polyps and also by the description of cancer arising within PJS polyps (26). According to Ohmiya et al., adenoma or adenocarcinoma was observed in 9 of 30 polyps (30.0 %) > 20 mm in size and in 1 of 80 polyps (1.3 %) ≤ 20 mm in size (p < 0.001) (17). However, other authors sate that dysplasia is found only rarely in PJS polyps. PJS polyps are polyclonal and only a minority of gastrointestinal cancers in PJS is diagnosed in surveillance exams. Some authors consider that hamartomatous polyp formation in PJS is the result of mucosal prolapse due to a germline disruption of a polarity pathway. This implies that hamartomatous polyps observed in PJS are an epiphenomenon to the cancer prone condition, instead of obligate malignant precursors, and that the rare cases of dysplasia and cancer arising in PJS polyps may be due to the prolapse of the mucosa containing small sporadic adenomas (27). One can thus hypothesize that hamartomas have none or small potential for malignization and that small-bowel cancer may arise from flat mucosa, possibly due to increased neoplastic initiation or accelerated carcinogenesis. Therefore, it is unclear if the removal of small-bowel polyps could potentially decrease the risk for malignancies by removal of precursor lesions. Follow up of patients submitted to surveillance and endoscopic polypectomy may help to clarify this issue. Based on these conflicting results we think that the retrieval of polyps larger than 20 mm may be considered.

The major drawbacks of this study are related with its retrospective nature and limited number of patients. Nevertheless, due to its long follow-up time and large number of polypectomies it allows us to draw some conclusions regarding efficacy and safety.

In conclusion, we highlight the role of DBE as a safe and effective therapeutic option for small-bowel polyps in PJS that avoids the need for laparotomy. DBE polypectomy might preclude complications of PJS, including intussusception, bleeding, and eventually malignancy, thereby obviating the need for emergency laparotomies. The effect of such an approach remains to be established in prospective trials.

References

1. Hemminki A, Markie D, Tomlinson I, Avizienyte E, Roth S, Loukola A, et al. A serine/threonine kinase gene defective in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Nature 1998;391:184-7. [ Links ]

2. Volikos E, Robinson J, Aittomäki K, Mecklin JP, Järvinen H, Westerman AM, et al. LKB1 exonic and whole gene deletions are a common cause of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. J Med Genet 2006;43:e18. [ Links ]

3. Aretz S, Stienen D, Uhlhaas S, Loff S, Back W, Pagenstecher C, et al. High proportion of large genomic STK11 deletions in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Hum Mutat 2005;26:513-9. [ Links ]

4. Giardiello FM, Trimbath JD. Peutze-Jeghers syndrome and management recommendations. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006;4:408-15. [ Links ]

5. Utsunomiya J, Gocho H, Miyanaga T, Hamaguchi E, Kashimure A. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: its natural course and management. Johns Hopkins Med J 1975;136:71-82. [ Links ]

6. McGarrity TJ, Kulin HE, Zaino RJ. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:596-604. [ Links ]

7. Gammon A, Jasperson K, Kohlmann W, Burt RW. Hamartomatous polyposis syndromes. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2009;23:219-31. [ Links ]

8. van Lier MG, Mathus-Vliegen EM, Wagner A, van Leerdam ME, Kuipers EJ. High cumulative risk of intussusception in patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: Time to update surveillance guidelines? Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106:940-5. [ Links ]

9. van Lier MG, Westerman AM, Wagner A, Looman CW, Wilson JH, de Rooij FW, et al. High cancer risk and increased mortality in patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Gut 2011;60:141-7. [ Links ]

10. Giardiello FM, Brensinger JD, Tersmette AC, Goodman SN, Petersen GM, Booker SV, et al. Very high risk of cancer in familial Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Gastroenterology 2000;119:1447-53. [ Links ]

11. Beggs AD, Latchford AR, Vasen HF, Moslein G, Alonso A, Aretz S, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: A systematic review and recommendations for management. Gut 2010;59:975-86. [ Links ]

12. Yamamoto H, Sekine Y, Sato Y, Higashizawa T, Miyata T, Iino S, et al. Total enteroscopy with a nonsurgical steerable double-balloon method. Gastrointest Endosc 2001;53:216-20. [ Links ]

13. Yamamoto H, Kita H. Double-balloon endoscopy: From concept to reality. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2006;16:347-61. [ Links ]

14. Ohmiya N, Taguchi A, Shirai K, Mabuchi N, Arakawa D, Kanazawa H, et al. Endoscopic resection of Peutz-Jeghers polyps throughout the small intestine at double-balloon enteroscopy without laparotomy. Gastrointest Endosc 2005;61:140-7. [ Links ]

15. Gao H, van Lier MG, Poley JW, Kuipers EJ, van Leerdam ME, Mensink PB. Endoscopic therapy of small-bowel polyps by double-balloon enteroscopy in patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Gastrointest Endosc 2010;71:768-73. [ Links ]

16. Sakamoto H, Yamamoto H, Hayashi Y, Yano T, Miyata T, Nishimura N, et al. Nonsurgical management of small-bowel polyps in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome with extensive polypectomy by using double-balloon endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2011;74:328-33. [ Links ]

17. Ohmiya N, Nakamura M, Takenaka H, Morishima K, Yamamura T, Ishihara M, et al. Management of small-bowel polyps in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome by using enteroclysis, double-balloon enteroscopy, and videocapsule endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2010;72:1209-16. [ Links ]

18. Plum N, May AD, Manner H, Ell C. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: Endoscopic detection and treatment of small bowel polyps by double-balloon enteroscopy. Z Gastroenterologie 2007;45:1049-55. [ Links ]

19. Aaltonen LA, Jarvinen H, Gruber SB, Billaud M, Jass JR. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. In: Hamilton S, LA Aaltonen, editors. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Digestive System. Lyon: IARC Press; 2000. p. 74-6. [ Links ]

20. Caspari R, von Falkenhausen M, Krautmacher C, Schild H, Heller J, Sauerbruch T. Comparison of capsule endoscopy and magnetic resonance imaging for the detection of polyps of the small intestine in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis or with Peutz-Jeghers' syndrome. Endoscopy 2004;36:1054-9. [ Links ]

21. Burke CA, Santisi J, Church J, Levinthal G. The utility of capsule endoscopy small bowel surveillance in patients with polyposis. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100:1498-502. [ Links ]

22. Mathus-Vliegen EM, Tytgat GN. Intraoperative endoscopy: Technique, indications, and results. Gastrointest Endosc 1986;32:381-4. [ Links ]

23. Mensink PB, Haringsma J, Kucharzik T, Cellier C, Pérez-Cuadrado E, Mönkemüller K, et al. Complications of double balloon enteroscopy: A multicenter survey. Endoscopy 2007;39:613-5. [ Links ]

24. Möschler O, May A, Müller MK, Ell C. Complications in and performance of double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE): Results from a large prospective DBE database in Germany. Endoscopy 2011;43:484-9. [ Links ]

25. Wang ZJ, Ellis I, Zauber P, Iwama T, Marchese C, Talbot I, et al. Allelic imbalance at the LKB1 (STK11) locus in tumours from patients with Peutz-Jeghers' syndrome provides evidence for a hamartoma-(adenoma)-carcinoma sequence. J Pathol 1999;188:9-13. [ Links ]

26. Bouraoui S, Azouz H, Kechrid H, Lemaiem F, Mzabi-Regaya S. Peutz-Jeghers' syndrome with malignant development in a hamartomatous polyp: Report of one case and review of the literature. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 2008;32:250-4. [ Links ]

27. Jansen M, de Leng WW, Baas AF, Myoshi H, Mathus-Vliegen L, Taketo MM, et al. Mucosal prolapse in the pathogenesis of Peutz-Jeghers polyposis. Gut 2006;55:1-5. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Miguel Serrano.

Serviço de Gastrenterologia.

Instituto Português de Oncologia de Lisboa Francisco Gentil,

E.P.E. Rua Professor Lima Basto,

1099-023 Lisboa, Portugal

e-mail: mmserrano@gmail.com

Received: 16-09-2013

Accepted: 13-12-2013