Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

versión impresa ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.107 no.7 Madrid jul. 2015

ORIGINAL PAPERS

Implication of the presence of a variant hepatic artery during the Whipple procedure

Implicaciones de las variantes arteriales hepáticas durante la duodenopancreatectomía cefálica oncológica

Mercedes Rubio-Manzanares-Dorado, Luis Miguel Marín-Gómez, Daniel Aparicio-Sánchez, Gonzalo Suárez-Artacho, Carmen Bellido, José María Álamo, Juan Serrano-Díaz-Canedo, Francisco Javier Padillo-Ruiz and Miguel Ángel Gómez-Bravo

HBP Surgery and Liver Transplantation Unit. General and Digestive Surgery. Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío. Sevilla, Spain

ABSTRACT

Introduction: The anatomical variants of the hepatic artery may have important implications for pancreatic cancer surgery. The aim of our study is to compare the outcome following a pancreatoduodenectomy (PD) in patients with or without a variant hepatic artery arising from superior mesenteric artery.

Material and methods: We reviewed 151 patients with periampullary tumoral pathology. All patients underwent oncological PD between January 2005 and February 2012. Our series was divided into two groups: Group A: Patients with a hepatic artery arising from superior mesenteric artery; and Group B: Patients without a hepatic artery arising from superior mesenteric artery. We expressed the results as mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables and percentages for qualitative variables. Statistical tests were considered significant if p < 0.05.

Results: We identified 11 patients with a hepatic artery arising from superior mesenteric artery (7.3%). The most frequent variant was an aberrant right hepatic artery (n = 7), following by the accessory right hepatic artery (n = 2) and the common hepatic artery trunk arising from the superior mesenteric artery (n = 2). In 73% of cases the diagnosis of the variant was intraoperative. R0 resection was performed in all patients with a hepatic artery arising from superior mesenteric artery. There were no significant differences in the tumor resection margins and the incidence of postoperative complications.

Conclusion: Oncological PD is feasible by the presence of a hepatic artery arising from superior mesenteric artery. The complexity of having it does not seem to influence in tumor resection margins, complications and survival.

Key words: Pancreatic cancer. Pancreatoduodenectomy. Aberrant hepatic artery. Accessory hepatic artery.

RESUMEN

Introducción: las variantes anatómicas de la arteria hepática pueden tener importantes implicaciones en la cirugía oncológica del páncreas. Nuestro objetivo es comparar los resultados tras un procedimiento de Whipple en pacientes con y sin presencia de una arteria hepática variante procedente de la arteria mesentérica superior.

Material y métodos: estudio analítico observacional retrospectivo en el que hemos analizado 151 pacientes con patología tumoral periampular sometidos a una duodenopancreatectomía desde enero de 2005 hasta febrero de 2012. Diferenciamos entre 2 grupos: grupo A (variante de la arteria hepática) y grupo B (no evidencia de variante de la arteria hepática). Hemos expresado los resultados como la media ± desviación estándar para las variables continuas y porcentajes para las cualitativas. Los test estadísticos fueron considerados significativos si la p < 0,05.

Resultados: hemos detectado 11 pacientes con anomalías de la arteria hepática (7,3%). La variante más frecuentemente fue la arteria hepática derecha aberrante (n = 7), seguida de la arteria hepática derecha accesoria (n = 2) y tronco de la arteria hepática común procedente de la arteria mesentérica superior (n = 2). En el 73% de los casos la detección de la variante arterial fue intraoperatoria. En todos los pacientes se realizó una resección R0. No se han apreciado diferencias significativas en los márgenes de resección tumoral, complicaciones, ni en la supervivencia.

Conclusión: la cirugía oncológica de la región céfalo-pancreática en presencia de una variante de la artería hepática es factible. La complejidad que supone tener una variante anatómica de la arteria hepática no parece influir en los márgenes de resección tumoral, complicaciones o supervivencia.

Palabras clave: Cáncer de páncreas. Duodenopancreatectomía. Arteria hepática aberrante. Arteria hepática accesoria.

Introduction

Anatomic abnormalities of the hepatic artery are common in the general population. Its prevalence ranges from 25-45% (1-4). The most frequent arterial variant is the aberrant right hepatic artery arising from the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) followed by aberrant left hepatic artery originated from the left gastric artery (1). The presence of a right hepatic artery (RHA) branch from SMA during pancreatic cancer surgery may have important implications. First, RHA branch from SMA has high chances of being encompassed by cephalo-pancreatic tumors (5). During surgery it is possible to injury a hepatic artery arising from SMA or otherwise may compromise the R0 resection in an attempt to preserve it. Thus, their presence may involve longer operative time and, consequently, increased postoperative morbidity and mortality.

However, the potential impact of a hepatic artery (HA) arising from SMA in pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) is not well known. The main objective of this study is to analyze the frequency of anatomical variants in our area and to assess the surgical and oncological implications in the presence of a HA arising from SMA during oncological PD by means comparing the postoperative morbidity and mortality.

Material and methods

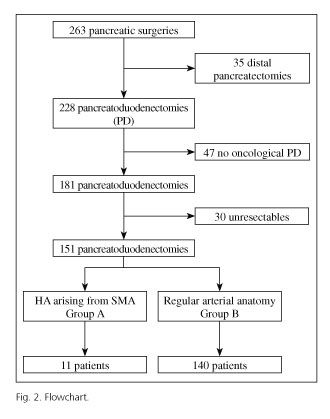

Descriptive and analytical observational study where we retrospectively analyzed 263 cases who underwent pancreatic surgery at the Hospital Universitario "Virgen del Rocío" (Seville, Spain) from January 2005 to February 2012. To avoid bias we have established these criteria; patients diagnosed of periampullary malignancy (ampulloma, adenocarcinoma of the pancreas or duodenum, neuroendocrine tumors and distal cholangiocarcinomas) that undergone an oncologic PD or total pancreatectomy. We excluded non-neoplasic cases and non-periampullary tumors. Non resectable cases also were excluded.

We divided the series into 2 groups based on the finding or not of a HA arising from SMA during the perioperative period (diagnosed by preoperative imaging test or during surgery). Group A included pancreatic resections with HA arising from SMA and group B included patients with hepatic vascular anatomy unchanged.

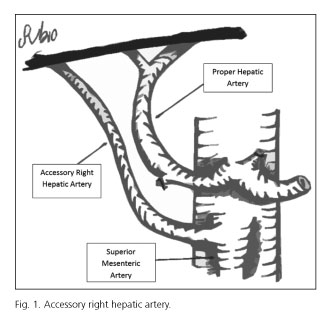

Hepatic arterial variants can be defined as aberrant or accessory. Aberrant right hepatic artery is defined as a unique right hepatic artery originating from SMA (5). When the right hepatic lobe is irrigated by two arteries, one right hepatic arising from the hepatic artery and another right hepatic artery from SMA, we say that the latter is an accessory right hepatic artery (5) (Fig. 1). For preoperative study, we used ultrasound + abdominal angio-CT or ultrasound + abdominal angio-CT + abdominal MRI. They were performed by two radiologists dedicated exclusively to abdominopelvic digestive pathology on their daily medical activity. We did not use mesenteric trunk arteriography.

We valued the specificity and sensitivity of radiological tests for the preoperative diagnosis of arterial anatomic variants through the tools provided on the web "www.imim.es/ofertadeserveis/softward-public/granmo/".

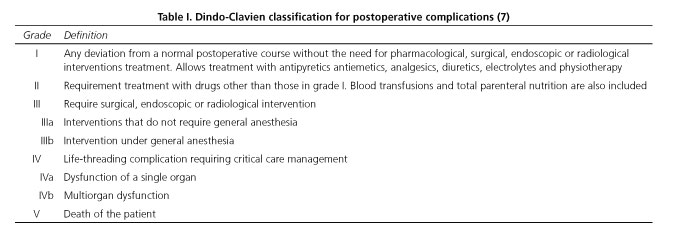

The preoperative variables were age, gender, anesthetic risk (according to the American Society of Anesthesiologists) (6) and the radiological diagnosis of RHA arising from SMA by angio-CT/MRI (yes/no). The intraoperative variables were operating time, the number of red blood packed cells transfused during surgery and intraoperative detection of RHA arising from SMA. Finally, postoperative variables were hospital stay, mortality, postoperative morbidity, resection type (R0, R1 or R2) and the existence of positive nodes in the surgical specimen. Operating time was defined as time (minutes) quantified, between the beginning of the skin incision until the end of closing. To evaluate postoperative morbidity, we use Clavien-Dindo classification (7) (Table I). Regarding the type of resection, we used the criteria of the American Joint Commission on Cancer Staging Manual (6th edition) once performed the pathological anatomical study (8). We considered R0 the absence of tumor cells in all resection margins; R1 if tumor cells were detected less than 1 mm from the resection margin; R2 if there were evidence of macroscopic tumor (9). Tumor resection margins studied were: Section of the distal bile duct, retroportal plane and the edge of pancreatic section. In all cases a sheet of 3 mm from the pancreatic remnant was sent intraoperatively before doing the pancreato-jejunal anastomoses.

We have got highly standardized the different steps of the oncologic PD. Through a wide Kocher maneuver we expose the SMA origin and confirm the absence of tumor infiltration. To identify the presence of a RHA arising from SMA, we systematically palpate the free edge of the hepatoduodenal ligament. At this level, it runs postero-lateral to the common hepatic duct, where the pulse of the accessory artery is felt. Likewise, we meticulously dissected the main biliary duct to prevent inadvertent ligation of the RHA arising from SMA. As part of lymphadenectomy, we proceed to the disection of the portal vein and common hepatic artery. RHA should be released to its origin in the SMA. The digestive continuity was rebuilt by means a Roux-en-Y loop in all patients underwent PD with reconstruction. We used a two layers for pancrato-jejuno anastomoses: Ducto-mucosa with loose point of Maxon loop 5/0 and a second sero- serous layer with a continuous suture (Prolene 4/0). Patients were followed for our service for 5 years from the surgery. We performed an abdominal CT scan every 6 months for the first two years and each year after the third year. Once this period over, patients were discharged from our office.

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS version 15.0 software for Windows. We valued if the variable was normally distributed by Kolmorogov-Smirnov test. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD. Categorical variables were expressed as percentages. Statistical significance was calculated using the Chi-square test, Fisher exact test and t-Student or U-Mann Whitney test. "p" value less than 0.05 was used to indicate statistical significance.

Results

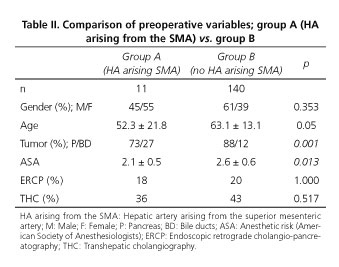

Of 263 cases undergoing pancreatic surgery at the Hospital Universitario "Virgen del Rocío" from January 2005 to February 2012, 47 cases were non-oncological pancreatic surgery, 30 were non-resectable and 35 underwent distal pancreatectomy cancer. A total of 151 patients underwent an oncological PD during the period between January 2005 and February 2012 (Fig. 2). We diagnosed 11 patients (7.2%) with HA arising from SMA. Of these, 7 cases had got an aberrant RHA, 2 cases an accessory RHA and in two patients a common hepatic artery arising from SMA. Preoperative and demographic data of groups A and B are shown in table II.

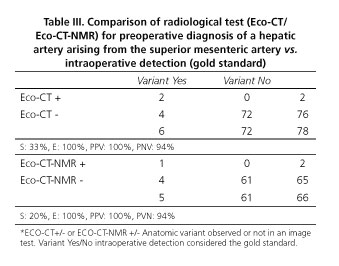

Preoperative radiological diagnosis of arterial variant was done only in 3 cases (27%), 2 by CT and 1 by MRI. Remaining cases were identified during surgical dissection. Sensitivity (S) and specificity (E) of ultrasound + abdominal angio-CT association for detecting a variation in the preoperative study provided a S = 33% and E = 100%. Moreover, the association of ultrasound + angio-CT+ MRI reported an S = 20% and E = 100% (Table III).

In 10 of 11 cases, variant artery arising from the SMA followed a posterior trajectory behind pancreas head and postero-lateral trajectory to portal trunk without being infiltrated by the tumor. In one case, the aberrant RHA was infiltrated by the tumor. It was necessary to do a resection with anastomose to remove the tumor. In-block resection with the head of the pancreas was performed. Aberrant RHA was sutured to the stump of gastroduodenal artery. There was no case of involuntary vessel injury during surgery.

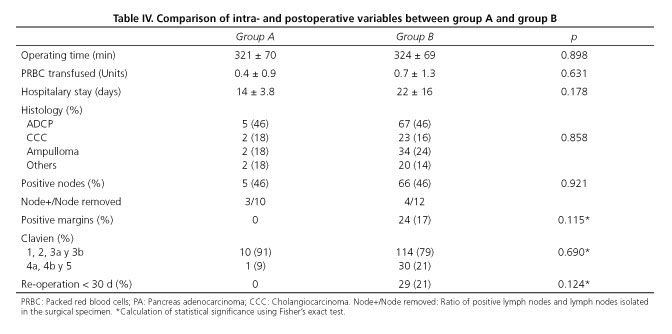

The presence of a HA arising from SMA does not seem to influence in surgery duration or intraoperative transfusions. We have not observed significant differences between groups. Neither it appears to increased morbidity nor postoperative stay (p = 0.17). From oncological point of view, histological distribution of resected tumors, tumor resection margins and presence of positive nodes did not shown significant differences.

It is remarcable that R0 resection was obtained in all patients in group A (0% with positive margins). We detected 17% of positive margin in group B. All affected margins corresponding to the retroportal sheet. Within the group A we have registered 5 deaths. In 4 cases was due to the progression of the tumor disease and in one case the patient died in the immediate postoperative period (first 30 postoperative days) due to thrombosis of mesenteric vein.

Discussion

Hepatic arterial variants are common in the general population. For this reason, the pancreatic surgeon should have an extensive knowledge of hepatic arterial anatomy and its possible variants. It is estimated that up to 41% of the population may have some variant hepatic artery (11,12). The main abnormality found in the literature is the right hepatic artery arising from the superior mesenteric artery, whose incidence is between 13 to 26% (11,13). In our series, the distribution of the variant has been of 7 aberrant RHA, 2 accessory RHA, and 2 common HA arising from SMA. This implies an overall variant prevalence of 7.2%, somewhat lower than the percentage observed in the literature (5). The term "accessory" is used when the variant coexisting with the normal anatomy. In its absence, the variant is called "aberrant".

Classically, the presence of an arterial variant could be a contraindication for surgery (12). Nowadays, we know that oncologic surgery of the head of the pancreas is feasible in the presence of a variant hepatic artery (5). Arterial variant involves a technical difficulty that may determine a more conservative resection of the pancreas, especially for retropancreatic plane and lead an inadequate removal of the tumor (9). By contrast, a more aggressive surgery that tries to keep this variant may increase the operating time, greater blood loss postoperative morbidity. There are few studies that support these theories. Although in the study by Jha et al. (5) there is a slight tendency toward increased blood loss and longer operative time in the RHA variant group, there were not statistical significance. In agreement with the published literature, we have observed a slight increase in operating time in the group A. No statistical significance was observed. We have neither observed difference in the number of intraoperative transfused red blood packed cells. According to Jah et al. (5), the incidence of vascular injuries described during PD is probably higher than the reported 3%. The great variability of this anatomical area contributes to vascular lesions. If we add an inflammatory process like a pancreatitis or a peritumoral desmoplastic reaction, the likelihood of vascular injury increases.

Currently, the use of angio-CT to study the relationship between the tumor site and mesenteric axis (14,15) is recommended. However, in our experience, arterial phase CT only showed the presence of a variant in 27% of cases. Despite which, there was no case of inadvertent arterial variant injuries.

In our series, the presence of a variant hepatic artery appears to have no impact on the radicality of tumor resection. All group A patients had a surgery with a complete R0 resection. A careful technique performed by expert hands may be sufficient to prevent inadvertent injury. Therefore, if the variant presents an intraparenchymal course or is infiltrated by the tumor, it may be necessary to perform an arterial resection and later revascularization (10). Although no significant differences were found between the two groups, it is remarkable that 17% in group B showed positive margins versus 0% in patients with hepatic arterial variant. Probably the presence of a RHA influenced in making a more radical and meticulous resection of the retropancreatic margin.

According to Jah et al. (5) variant of the right hepatic artery may have three different courses in relation to the head of the pancreas, which may have important consequences for pancreaticoduodenectomy (5).

The implications of the loss of hepatic arterial flow are well known in liver transplantation (4). However, in the context of a PD are not so clear. Although we have not identified any inadvertent section of the variants in our study, there are some case-series that reported compatible findings with hepatic necrosis or ischemia of the hepato-jejunal anastomosis (16-18). In the context of PD, the iatrogenic injury of a RHA may pose a risk that leads to a biliary fistula secondary to an ischemic hepato-jejunal anastomoses ischemia, despite the existence of a hiliar vascularization. Some authors refer bile duct ischemia after ligation of the common hepatic artery (19). The revascularization is essential if there is a commitment aberrant right hepatic artery, aberrant common hepatic artery or an accessory RHA with a high flow to the right lobe. In a patient with jaundice, preservation of adequate vascularity may still be mandatory. An improper vascularization may delay the restoration of liver function. Different authors recommend arterial reconstruction in case of tumor infiltration or in cases where the intraparenchymal course not ensure an R0 resection (5,10,20,21). There are many arterial reconstructive techniques for the RHA after section. Some reports describe techniques with the interposition of a vein or prosthetic graft (22,23).The prosthetic material has the disadvantage of being inserted into a field that is not completely sterile after performing the corresponding anastomoses of the PD. On the other hand, both grafts required to perform two anastomoses. The technique of transposition of the gastroduodenal artery described above, eliminates the need for grafts or prosthesis, providing an adequate blood flow with an artery with a similar size and a single anastomose, allowing the surgeon to achieve adequate tumor resection margin in a population with a unique features.

As conclusion, oncologic pancreatic surgery in presence of a variant hepatic artery is feasible. Anatomical variant diagnosis is mainly done during surgery. CT and MRI have low sensitivity for detection of arterial anomalies; however in hands of surgeons with extensive experience, the complexity of having a variant hepatic artery, not seem to influence in tumor resection margins, postoperative complications or survival.

References

1. Saeed M, Murshid KR, Rufai AA, et al. Coexistence of multiple anomalies in the celiac mesenteric arterial system. Clinical Anatomy 2003;16:30-6. DOI: 10.1002/ca.10093. [ Links ]

2. Nelson TM, Polak R, Jonasson O, et al. Anatomic variants of the celiac, superior mesenteric, and inferior mesenteric arteries and their clinical relevance. Clin Anat 1988;1:75-91. DOI: 10.1002/ca.980010202. [ Links ]

3. Makisalo H, Chaib E, Krokos N, et al. Hepatic arterial variations and liver-related diseases of 100 consecutive donors. Transpl Int 1993;6:325-9. DOI: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.1993.tb00675.x. [ Links ]

4. Marín-Gómez LM, Gómez-Bravo MA, Bernal-Bellido C, et al. Variability of the extrahepatic arterial anatomy in 500 hepatic grafts. Transplant Proc 2010;42:3159-61. DOI: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.05.078. [ Links ]

5. Jah A, Jamieson N, Huguet E, et al. The Implications of the presence of an aberrant right hepatic artery in patients undergoing a pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surg Today 2009;39:669-74. DOI: 10.1007/s00595-009-3947-3. [ Links ]

6. American Society of Anesthesiologists. New classification of physical status. Anesthesiology 1963;24:111. [ Links ]

7. Clavien P, Barkun J, De Oliveira M, et al. The Clavien-Dindo Classification of Surgical Complications. Ann Surg 2009;250:187-96. DOI: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b13ca2. [ Links ]

8. Greene FL, Page DL, Fleming ID, et al., editores. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 6th ed. Berlin/ Heidelberg/ New York/ London/ Paris/ Tokyo/ Hong Kong: Springer-Verlag; 2002. p. 435. [ Links ]

9. Verbeke CS, Leitch D, Menon KV, et al. Redifining the R1 resection in pancreatic cancer. Br J Surg 2006;93:1232-37. DOI: 10.1002/bjs.5397. [ Links ]

10. Rubio-Manzanares M, Marín LM, Serrano J, et al. Reconstrucción de la arteria hepática derecha aberrante en la duodeno-pancreatectomía cefálica. Cir Esp 2014;92:284-96. DOI: 10.1016/j.ciresp.2013.05.003. [ Links ]

11. Kadir S, Lundell C, Saeed M. Coeliac. Superior and inferior mesenteric arteries In: Kadir S, editor. Atlas of normal and variant. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1991. p. 297-308. [ Links ]

12. Hiatt JR, Gabbay J, Busuttil RW. Surgical anatomy of the hepatic arteries in 10000 cases. Ann Surg 1994;220:50-2. DOI: 10.1097/00000658-199407000-00008. [ Links ]

13. Woods MS, Traverso LW. Sparing a replaced common hepatic artery during pancreaticoduodenectomy. Am Surg 1993;59:719-21. [ Links ]

14. Chamberlain, El-Sedfy A, Rajkumar D. Aberrant hepatic arterial anatomy and the Whipple procedure: Lessons Learned. Am Surg 2011;10:517-26. [ Links ]

15. Cloyd JM, Chandra V, Louie JD, et al. Preoperative embolization of replaced right hepatic artery prior to pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Surg Oncol 2012;106:509-12. DOI: 10.1002/jso.23082. [ Links ]

16. Allendorf JD, Bellemare S. Reconstruction of the replaced right hepatic artery at the time of pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Gastrointest Surg 2009;13:555-7. DOI: 10.1007/s11605-008-0578-8. [ Links ]

17. Schmidt SC, Settmacher U, Langrehr JM, et al. Management and outcome of patients with combined bile duct and hepatic arterial injuries after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surgery 2004;135:613-8. DOI: 10.1016/j.surg.2003.11.018 DOI: 10.1016/j.surg.2003.11.018. [ Links ]

18. Stewart L, Robinson TN, Lee CM, et al. Right hepatic artery injury associated with laparoscopic bile duct injury: Incidence, mechanism, and consequences. J Gastrointest Surg 2004;8:523-30. DOI: 10.1016/j.gassur.2004.02.010. [ Links ]

19. Deltenre P, Valla DC. Ischemic cholangiopathy. Semin Liver Dis 2008;28:235-46. DOI: 10.1055/s-0028-1085092. [ Links ]

20. Yamamoto S, Kubota K, Rokkaku K, et al. Disposal of replaced common hepatic artery coursing within the pancreas during pancreatoduodenectomy: Report of a case. Surg Today 2005;35:984-7. DOI: 10.1007/s00595-005-3040-5. [ Links ]

21. Amano H, Miura F, Toyota N, et al. Pancreatectomy with reconstruction of the right and left hepatic arteries for locally advanced pancreatic cancer. J HepatobiliaryPancreat Surg 2009;16:777-80. DOI: 10.1007/s00534-009-0202-7. [ Links ]

22. Hamazaki K, Mimua H, Kobayashi T. Hepatic artery reconstruction after resection of the hepatoduodenal ligament. Br J Surg 1991;78:1366-67. DOI: 10.1002/bjs.1800781131. [ Links ]

23. Danielson GK, Davis NP, Giffen WO. Successful resection of distal hepatic artery aneurysm with graft reconstruction of the hepatic arteries. Surgery 1968;63:722-6. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Mercedes Rubio-Manzanares-Dorado.

HBP Surgery and Liver Transplantation Unit.

General and Digestive Surgery.

Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío.

Av Manuel Siurot, s/n.

41013 Sevilla, Spain

e-mail: mercedesrmd@gmail.com

Received: 22-01-2015

Accepted: 21-03-2015

texto en

texto en