Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista de la Sociedad Española del Dolor

versión impresa ISSN 1134-8046

Rev. Soc. Esp. Dolor vol.25 no.6 Madrid nov./dic. 2018

https://dx.doi.org/10.20986/resed.2018.3673/2018

REVIEW

Evidence-based recommendations for the management of neuropathic pain (review of the literature)

1Médica Fisiatra. Esp. en salud ocupacional. Estudio y tratamiento del dolor. Fundación Santa Fe de Bogotá. Clínica de Ortopedia y accidente laborales. Bogotá, Colombia

2Médico Anestesiólogo. Especialista en Medicina del Dolor y Cuidados Paliativos. Unidad de Tratamiento de Dolor (UTD). Clínica del Country. Bogotá, Colombia

3Médica epidemiológica. Salud Pública. NeuroEconomix. Bogotá, Colombia

INTRODUCTION

Pain is currently considered a disease and not a symptom (World Health Organization, 2010), a condition of heterogeneous causality and presentation. The burden of the disease and health care costs are high for people affected by this condition 1,2,3,4. Mainly in non-specialized contexts, under-diagnosis is common5,6. The estimated prevalence of pain with neuropathic characteristics in the general population is 7-10% 3,7, however it may vary widely according to definitions, diagnostic criteria, evaluation methods and patient selection 1,2,8. According to the Latin American Federation of Associations for the Study of Pain, the most common cause of pain in Latin America was low back pain with neuropathic component (34% of patients) 9.

Problems associated with suboptimal identification, diagnostic inaccuracies and neuropathic pain management have been researched in various contexts. 39% of patients diagnosed with pain receive treatment prescribed by their physician 10. The major problems identified include inappropriate use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), widespread use of opioids as first-line treatment, and late referrals to specialized management with a multidisciplinary approach 1,11.

Most patients with possible neuropathic pain will be assessed at least initially by a primary care physician 12, and that is where pain assessment and management is initiated, considering that pharmacotherapy with first-line agents is simple and suitable for non-specialist physicians6. The purpose of this document is to synthesize, through a review of the literature, the current recommendations in the management of neuropathic pain in order to guide health professionals in the timely identification of this pathology and contribute to the process of informed clinical decision-making.

METHODOLOGY

Thematic review based on a highly sensitive literature search for the identification of clinical practice guidelines and systematic reviews of the literature for the management of neuropathic pain. This search was completed in August 2017 at the American Academy of Neurology, Canadian Pain Society, EFNS (European Federation of Neurological Societies), NICE (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence), RLDN (Latin-American network for the study and treatment of the neuropathic pain), and other expert recommendations based on evidence review. Search terms such as "pain management" AND "neuralgia" were used, including studies in English and Spanish, and full publications between 2012 and 2017.

From the references included, information related to definitions, relevant considerations, indications and treatment objectives, both pharmacological and non-pharmacological, and remission criteria was obtained.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The search initially yielded 45 potentially relevant studies, after the elimination of duplicates. In reviewing the title and summary of these articles, 34 clinical practice guidelines for the management of neuropathic pain were finally included. The most relevant aspects of the information evidenced in this review are presented below.

The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP 2011) defines neuropathic pain as "An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage" 10 and is currently recognized as "pain caused by an injury or disease of the sensory-somatic nervous system"(1,5).

There are two components that are integrated for the final perception of pain: 1) nociceptive or sensory, which constitutes the painful sensation and is a consequence of the transmission of stimuli through the nerve pathways to the cerebral cortex. Most available painkillers act on this component; and 2) affective or reactive, which determines the so-called "pain-related suffering" that varies widely depending on the cause, time, and experience of the patient, and is related to psychological factors10.

The most commonly used neuropathic pain classifications are based on the anatomy of injuries, aetiology, and related diseases10. It is located and distributed in three areas especially: 1) Central: when the main damage or disorder is located in the central nervous system; 2) Peripheral: if the main damage is located in the peripheral nervous system; and 3) Localized: well-defined and consistent area of maximum pain 6,13, equal to or less than that of a letter-sized page (21.6 x 27.9 cm) 14,15.

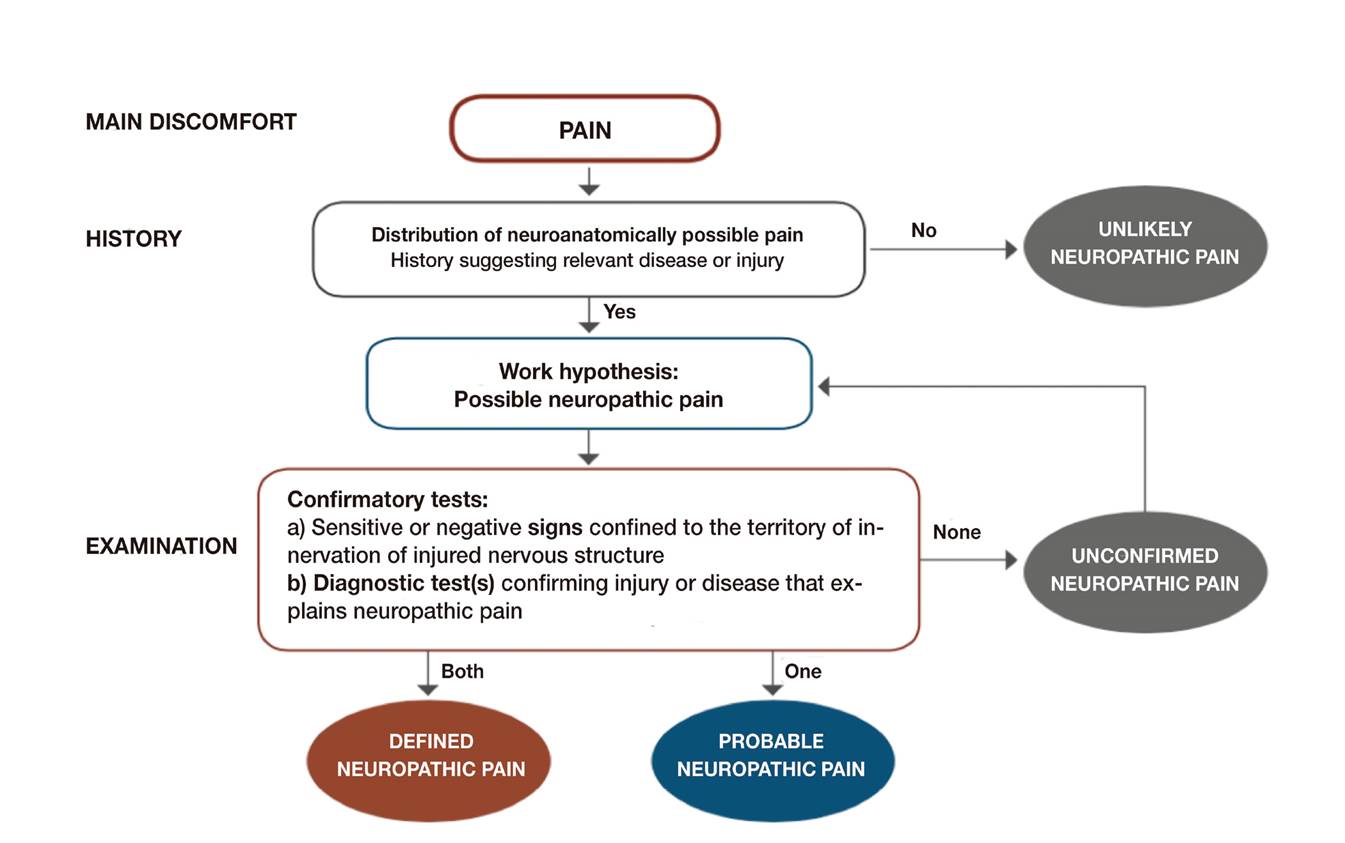

The assessment of neuropathic pain is based on clinical judgment and confirmatory diagnostic tests of abnormalities in sensory-somatic pathway function, however, neuropathic pain is primarily a clinical diagnosis. A simple diagnostic guidance algorithm grades the likelihood of neuropathic pain (Figure 1).

Diagnosis of Neuropathic Pain

Diagnosing neuropathic pain involves 3 aspects: patient history, physical examination of the patient, and follow-up of confirmation tests. One of these relevant aspects is the assessment of sensory signs, in which the patient describes the sensation after applying a precise and reproducible stimulus (touch, puncture, pressure, cold, heat, vibration), and their responses are classified as normal, decreased or increased, according to the evaluation of a loss (negative sensory signs) or a gain (positive sensory signs) of the sensory-somatic function 3.

In common practice, a history with suspicion of neuropathic pain and tests with confirmatory signs of sensory-somatic disturbance (compatible with neuropathic pain characteristics) make up a probable case of neuropathic pain. The "likely" level is usually sufficient to initiate treatment according to neuropathic pain guidelines. The "defined" level, by confirmatory tests compatible with the location and nature of the injury or disease, is useful in specialized contexts and when a causal treatment of the underlying injury or disease is an option. 16

Careful clinical examination is essential in the assessment of neuropathic pain. Presentation characteristics include 10:

Neuropathic pain can be intermittent/paroxysmal or constant, spontaneous (i.e. occurs without apparent stimulation) or caused.

Typical descriptions to describe painful and unpleasant sensations (dysesthesia) or altered sensations (paraesthesia) include: shots, like an electric shock, burning, tingling, squeezing, numbness, itching, throbbing and a prickling sensation1,5.

Other symptoms that manifest between 15-50% 17 include allodynia (pain caused by a stimulus that normally does not cause pain such as breeze, skin contact with clothing, temperature changes), hyperalgesia (an increased response to a stimulus that is usually painful), painful anaesthesia (pain felt in an anaesthetic area or region), and sensory gain or loss (IASP 2011) 1,5. They are named after the physical stimulus that causes them: heat, cold, pressure, for example allodynia to cold or heat or mechanical.

Screening Tools

There are several standardized screening tools to assist in the identification and classification of neuropathic pain, based on the patient's reported pain classification. Diagnostic accuracy is variable within and between patient populations, however, they are appropriate to increase patient identification due to the generally higher sensitivity (versus specificity) 12.

There are scales that differentiate neuropathic pain from a nociceptive pain, and others that allow characterizing symptoms. It is recommended to use those of self-administered neuropathic pain, validated in Spanish, to assist in early identification, prioritizing those that are simple to use and that can be quickly executed (Table 1)1,12). Questionnaire DN4 is widely accepted as easy, simple and has the greatest specificity and sensitivity 10.

TABLE I VALIDATED DETECTION TOOLS FOR NEUROPATHIC PAIN

I1: throbbing, tingling. I2: electric shock, shot. I3: hot, burning. I4: numbness. I5: pain evoked by soft touch. I6: cold, painful, freezing pain. I7: autonomic changes. I8: allodynia brushing. I9: threshold increased to soft touch. I10: threshold increased to puncture.

Sources: Adapted from Colloca L, et al. and Sociedad Española de Médicos de Atención Primaria (SEMERGEN), 2017. (3,10) / Adapted from Bennet MJ et al. Pain 2007

There are also different imaging techniques that can be used for the study of pain from the metabolic, functional and anatomical point of view 10:

Metabolic study: Positron Emission Tomography (PET), Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT) and magnetic resonance imaging. They allow the analysis of metabolic changes, including those related to neuronal integrity, excitability and inhibitory neurotransmitters, as well as agents involved in energy processing.

Functional study: functional magnetic resonance imaging (detects changes in blood oxygenation, reflections of changes in blood flow and variations in deoxyhaemoglobin levels), and nerve-conduction and electromyography (allow diagnosis of peripheral nerve injury or its entrapment, severity and prognosis) (18).

Structural or anatomical: anatomical magnetic resonance imaging to check that chronic pain is associated with certain structural changes in the brain.

Another simple examination-based way to identify peripheral neuropathy and differentiate it from nociceptive pain is the "3L" approach: Listen (listen to the verbal description of pain), Locate (locate the pain region and the document with a drawing of the pain, made by the patient or the physician), and Look (perform a simple examination of sensory-somatic functions, including sensitivity to touch, cold, heat, and pain) 1.

Principles of Neuropathic Pain Management

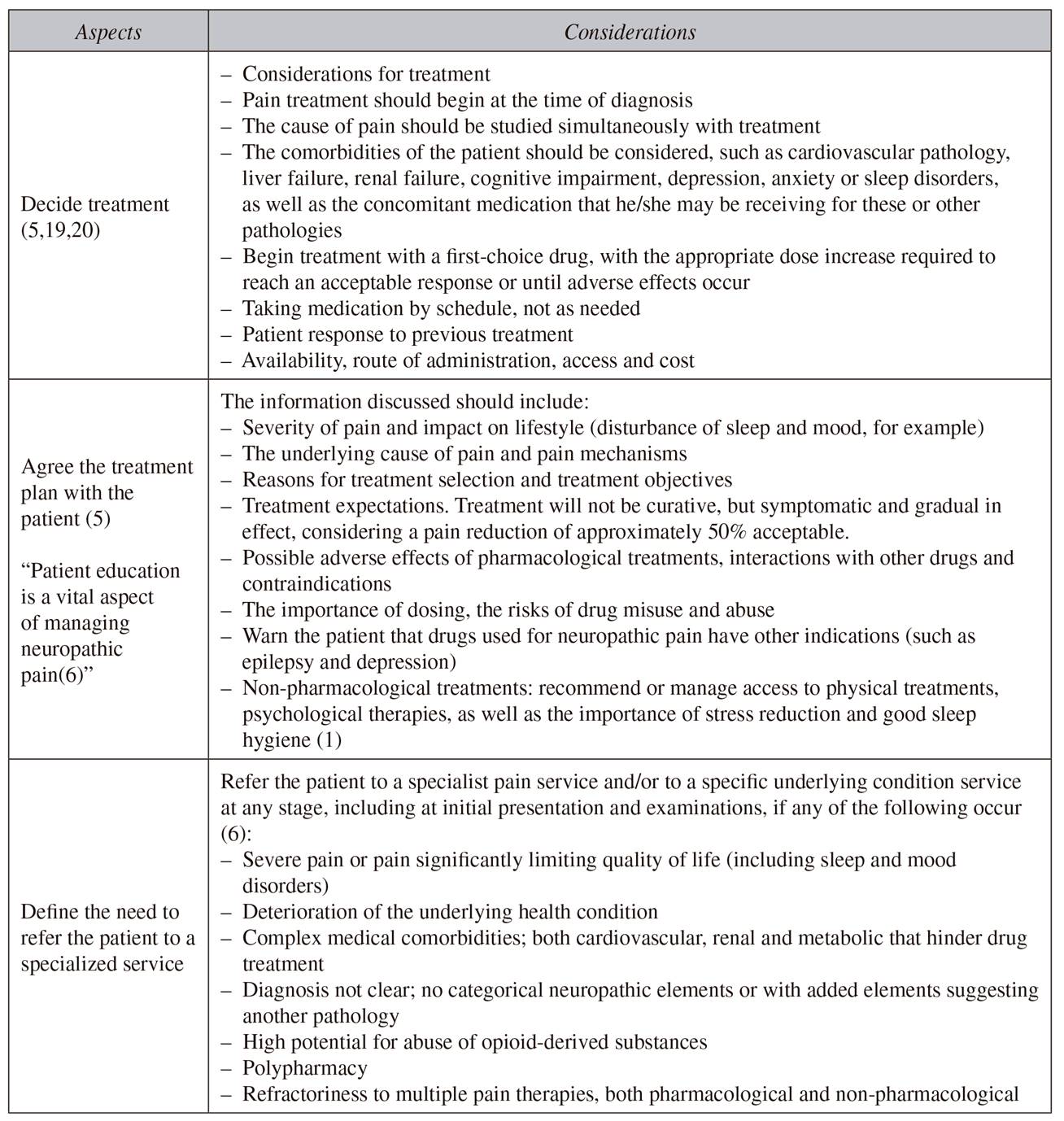

The main objective in most cases is to make the pain "bearable" or "tolerable", that is, on an analogous visual scale: set from 0 to 10, zero as no pain and 10 as the most unbearable pain, the objective would be 4/10. This setting of objectives can make a considerable difference in patient satisfaction when instituting pharmacological treatments 19. There are three essential aspects in the management of neuropathic pain, as described in Table 2.

Pharmacological Management of Pain

Peripheral Neuropathic Pain

First-line analgesics: options for first-line monotherapy (except trigeminal neuralgia) 1,3,5,10,19:

Tricyclic antidepressants (low dose amitriptyline 25 mg or other tricyclic antidepressants such as imipramine).

Α2δ ligands (pregabalin or gabapentin) (20).

Serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (duloxetine or venlafaxine). Of choice for when there are sleep or mood disorders.

As a special consideration, consideration should be given to the use of tramadol (atypical opioid) for the management of acute rescue therapy or incidental pain in combination with first-line drugs 5.

Patients should be assessed 2 to 4 weeks after starting the treatment to determine the response:

If the response is good, treatment should be maintained and if the response is maintained for 3 months, a slower titration can be attempted. If symptoms return, treatment should be titrated again at an effective dose.

If a partial response is observed within 2-4 weeks, consider increasing the dose of the current agent.

If the response is poor, or the drug is not tolerated, move to second-line approaches.

Second-line analgesics: if the initial treatment is not effective or is not tolerated, monotherapy should be changed or different classes of agent combined. The monotherapy change should be for one of the remaining drugs indicated in the first line (amitriptyline, duloxetine, gabapentin, or pregabalin) and consider changing again if the second and third drugs tested are not effective or are not tolerated 5,9.

Combined management considerations:

Combined therapy may offer additional analgesic benefits and benefits over the related symptoms, but the potential advantages should be weighed against the possibility of additional adverse effects, drug interactions, increased cost and reduced adherence to a more complex treatment regimen.

When treatment is withdrawn or changed, the decrease in drugs should be slow and progressive 5,6.

The combination of ≥ 2 analgesic agents in the treatment of neuropathic pain can improve analgesic efficacy and has the potential to reduce the profile of side effects if synergistic effects reduce the dose of combination drugs 9,19.

Combined treatment options 3,5:

Pregabalin or gabapentin with a serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor.

Pregabalin or gabapentin with amitriptyline 9.

Pregabalin or gabapentin with tramadol.

Although tricyclic antidepressants and serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors are different classes of antidepressants, they target the same mechanism, so a combination of serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants is not recommended 5, and the combination of tricyclic antidepressants with tramadol should be avoided.

Third-line analgesics: if the patient does not respond to drug change or combination therapy, the use of strong opioids is recommended; those most closely related to the management of neuropathic pain are: tapentadol, oxycodone, methadone and buprenorphine 21, since it is a partial, and not pure, agonist 22. As well as combinations of strong opioids with dual antidepressants or with pregabalin or gabapentin, with the exception of dual analgesia: tapentadol, which is suggested to be combined with dual antidepressants23.

Other analgesic options: There are weak, negative, or inconclusive recommendations for the use of all other pharmacological treatments for general neuropathic pain, although some agents are likely to be effective in subgroups of patients 3. The following should not be taken to treat neuropathic pain in non-specialized places unless directed by a specialist: lacosamide, lamotrigine, morphine, oxcarbazepine, topiramate, or venlafaxine 5.

Localized Neuropathic Pain

Localized neuropathic pain is a form of peripheral neuropathic pain. Topical treatments, the basis of localized neuropathic pain management, are especially useful to reduce the consumption of oral drugs due to low performance, low tolerance or polypharmacy. Similarly, they have been associated with satisfactory efficacy, improved performance and fewer systemic side effects and drug interactions 24. The application of topical agents has demonstrated good results in peripheral neuropathic pain, safety, tolerance and continuous efficacy throughout long-term treatment. Topical modalities may also be used in combination with other medications and analgesics with limited pharmacological interactions 25,26.

Lidocaine patches (5%) have demonstrated efficacy safety and tolerability in postherpetic neuralgia24,27. Several international guides, including the 2009 Latin American guide, place topical lidocaine as the first line in peripheral neuropathy1. Botulinum toxin type A has shown efficacy and safety in small clinical trials with subcutaneous administration in peripheral neuropathic pain 24,28, with a recommended dose of 50-200 units to the painful area every 3 months.

The management of localized neuropathic pain is based on topical therapy starting with lidocaine patches (5%), the first line being for its management 1,21, as other treatment options, especially for the management of refractory localized neuropathic pain, the use of botulinum toxin and the combined treatment described above is recommended, if there is no response to topical treatment.

The quality of evidence on the use of capsaicin patches (8%) is high (although they are not available in Colombia). NeuPSIG guidelines on neuropathic pain assessment proposed capsaicin patches as a second line of treatment for peripheral neuropathy when trying to avoid oral treatments or if these are not tolerated 16. However, the magnitude of the effect is less than lidocaine, more likely to produce topical side effects such as pain, erythema, pruritus, and mild to moderate transient burns in the area of application 24. The recommendation is to apply them in the area of pain every 6 hours with gloves, for 8 weeks.

The following have been described for the management of postherpetic neuralgia:

As a third line of treatment combine drugs of different classes that include strong opioids.

The following have been identified for the management of trigeminal neuralgia:

Carbamazepine (200-1,200 mg/day) as the drug of choice, however, its efficacy may be compromised by low tolerability and pharmacokinetic interactions (1,5,29).

If the initial treatment with carbamazepine is ineffective, not tolerated or contraindicated, a specialist's advice and early referral to a specialized pain service or condition-specific service should be considered 5.

Central Neuropathic Pain

Central neuropathic pain appears to respond to the same pharmacological treatments as peripheral neuropathic pain, although patients generally have a less robust response.

First-line analgesics:

Amitriptyline should be the preferred option recommended by experts.

Pregabalin and gabapentin. Based on scientific evidence and the added benefit in the treatment of comorbidities (depression, insomnia, anxiety), pregabalin should be the preferred option for patients aged over 65, with a better risk/benefit ratio compared to tricyclic antidepressants, and with less contraindications.

Second and third line analgesics:

Switch to another first-line agent or combine medications if treatment fails.

Tramadol followed by stronger opioids: tramadol, tapentadol, oxycodone, methadone and buprenorphine, due to their partial agonism and antineuropathic mechanism.

Other analgesic options:

Pharmacological Management of Neuropathic Pain

Complementary treatments such as psychotherapy (particularly cognitive behavioural therapy) and physiotherapy-physical means for pain 31 should be administered as part of a multidisciplinary approach1,8,9. Interventional treatments are considered for patients with refractory neuropathic pain, who have not responded adequately to standard pharmacological treatments used alone or in combination with non-pharmacological treatments 8,19.

Interventional treatments for the management of neuropathic pain should ideally be offered in clinical and research environments that collect and report data on patient outcomes8. Only qualified professionals with extensive experience should perform these interventional procedures 5.

Specific recommendations:

Sympathetic blocks and spinal cord stimulation in cases of pain that cannot be managed by pharmacological and complementary treatments 3 and are not candidates for corrective surgery (failed back surgery syndrome, permanent chronic postoperative pain and complex regional pain syndrome, traumatic neuropathy and brachial plexopathy) 8,32.

Stimulation of the peripheral nerve or dorsal root ganglion is recommended in chronic neuropathic pain, including occipital neuralgia and postherpetic neuralgia. Dorsal root ganglion stimulation provided a response rate with a pain reduction of up to 60% 3.

Epidural and transcranial cortical neurostimulation as treatment options for patients with chronic refractory neuropathic pain 3.

Bisphosphonates: have recommendation A in complex regional pain syndrome 33, can produce long-term benefits (> 1 month) in patients who have not responded adequately to less invasive options 3,32,33.

Recommendations for epidural injections 3,32:

Follow-up of Neuropathic Pain

Patients should be assessed 2 to 4 weeks after starting the treatment to determine the response. The tools and scales used for diagnosis may be useful for clinical monitoring (although not all are validated for this use) to establish a baseline and assess the patient's response.

Monitoring of possible drug interactions, adverse events, comorbidities, need for dose assessment, etc., should be part of the follow-up plan. If a patient does not show a satisfactory therapeutic response, he/she should be referred to a pain centre.

Each follow-up should include assessment of: pain management, lifestyle impact, daily activities (including sleep disorders), physical and psychological well-being, adverse effects, and continued need for treatment.

CONCLUSIONS

Neuropathic pain is a common in health care services, where the non-pain specialist can perform the diagnosis based on the clinical history and directed physical examination. The treatment must be multidisciplinary and begin early with first-line drugs. The first-line treatments recommended by most guides are tricyclic antidepressants, α2δ-ligands (pregabalin and gabapentin), with selective serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors sometimes included as first-line and sometimes as second-line. In localized neuropathic pain, the recommended first line is lidocaine patches (5%).

All guides recommend reserving tramadol for second-line use in stronger opioid rescue therapy and analgesics for later use, and only after non-response to another monotherapy or combination therapy with first-line agents. Evidence in central neuropathic pain is less consistent than for peripheral neuropathic pain, but first-line recommendations are amitriptyline and gabapentin or pregabalin.

Complementary therapies (psychotherapies and physiotherapy) are recommended to accompany drug management. The evidence for most interventionist treatments is weak, limited or insufficient, some evidence supports these recommendations under selected conditions of neuropathic pain.

The dissemination of risk and benefit evidence of available therapeutic options is necessary for shared decision-making and informed consent 32, as well as to ensure that persons requiring evaluation and specialized interventions are referred in a timely manner to a specialized pain management service and/or other specific services 5.

BIBLIOGRAFÍA

1. Chetty S, Baalbergen E, Bhigjee A, Kamerman P, Ouma J, Raath R, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for management of neuropathic pain: expert panel recommendations for South Africa. SAMJ South Afr Med J 2012;102(5):312-25. [ Links ]

2. Torrance N, Ferguson JA, Afolabi E, Bennett MI, Serpell MG, Dunn KM, et al. Neuropathic pain in the community: more under-treated than refractory? Pain 2013;154(5):690-9. DOI: 10.1016/j.pain.2012.12.022. [ Links ]

3. Colloca L, Ludman T, Bouhassira D, Baron R, Dickenson AH, Yarnitsky D, et al. Neuropathic pain. Nat Rev Dis Primer 2017;3:17002. DOI: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.2 [ Links ]

4. Smith BH, Hardman JD, Stein A, Colvin L. Managing chronic pain in the non-specialist setting: a new SIGN guideline. Br J Gen Pr 2014;64(624):e462-4. DOI: 10.3399/bjgp14X680737. [ Links ]

5. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Neuropathic pain in adults: pharmacological management in non-specialist settings | Guidance and guidelines | NICE [Internet]. [citado el 27 de agosto de 2017]. Disponible en: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg173. [ Links ]

6. Correa-Illanes G. Dolor neuropático, clasificación y estrategias de manejo para médicos generales. Rev Médica Clínica Las Condes 2014;25(2):189-99. DOI: 10.1016/S0716-8640(14)70030-6. [ Links ]

7. VanDenKerkhof EG, Mann EG, Torrance N, Smith BH, Johnson A, Gilron I. An epidemiological study of neuropathic pain symptoms in Canadian adults. Pain Res Manag 2016. DOI: 10.1155/2016/9815750. [ Links ]

8. Dworkin RH, O'Connor AB, Kent J, Mackey SC, Raja SN, Stacey BR, et al. Interventional management of neuropathic pain: NeuPSIG recommendations. Pain 2013;154(11):2249-61. DOI: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.06.004. [ Links ]

9. Amescua-García C, Colimon F, Guerrero C, Jreige Iskandar A, Berenguel Cook M, Bonilla P, et al. Most Relevant Neuropathic Pain Treatment and Chronic Low Back Pain Management Guidelines: A Change Pain Latin America Advisory Panel Consensus. Pain Med 2018;19(3):460-70. DOI: 10.1093/pm/pnx198. [ Links ]

10. Canós Verdecho MÁ, Llona MJ, Barrés Carsí M, Ibor Vidal PJ. Diagnóstico y tratamiento del dolor neuropático periférico y localizado. Sociedad Española de Médicos de Atención Primaria (SEMERGEN); 2017. [ Links ]

11. Martínez V, Attal N, Vanzo B, Vicaut E, Gautier JM, Bouhassira D, et al. Adherence of French GPs to chronic neuropathic pain clinical guidelines: Results of a cross-sectional, randomized,"e" case-vignette survey. PloS One 2014;9(4):e93855. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093855. [ Links ]

12. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. Diagnostic Methods for Neuropathic Pain: A Review of Diagnostic Accuracy; 2015. [ Links ]

13. Mick G, Baron R, Finnerup NB, Hans G, Kern KU, Brett B, et al. What is localized neuropathic pain? A first proposal to characterize and define a widely used term. Pain 2012;2(1):71-7. DOI: 10.2217/pmt.11.77. [ Links ]

14. Casale R, Mattia C. Building a diagnostic algorithm on localized neuropathic pain (LNP) and targeted topical treatment: focus on 5% lidocaine-medicated plaster. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2014;10:259. DOI: 10.2147/TCRM.S58844. [ Links ]

15. Pasternak D, Sánchez F, Sánchez A, Reyes E, Chehab J, Orellana I, et al. Dolor neuropático localizado, conceptualización y manejo en la práctica médica general: consenso de un grupo de expertos. Rev Iberoam Dolor [Internet] 2010;5(1). Disponible en: http://www.revistaiberoamericanadedolor.org [ Links ]

16. Finnerup NB, Haroutounian S, Kamerman P, Baron R, Bennett DL, Bouhassira D, et al. Neuropathic pain: an updated grading system for research and clinical practice. Pain. 2016;157(8):1599-606. DOI: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000492. [ Links ]

17. Jensen TS, Finnerup NB. Allodynia and hyperalgesia in neuropathic pain: clinical manifestations and mechanisms. Lancet Neurol 2014;13(9):924-35. DOI: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70102-4. [ Links ]

18. Quan D, Bird SJ. Nerve conduction studies and electromyography in the evaluation of peripheral nerve injuries. Univ Pa Orthop J 1999;12:45-51. [ Links ]

19. Moulin D, Boulanger A, Clark AJ, Clarke H, Dao T, Finley GA, et al. Pharmacological management of chronic neuropathic pain: revised consensus statement from the Canadian Pain Society. Pain Res Manage. 2014;19(6):328-35. [ Links ]

20. Kremer M, Salvat E, Muller A, Yalcin I, Barrot M. Antidepressants and gabapentinoids in neuropathic pain: Mechanistic insights. Neuroscience 2016;338:183-206. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.06.057. [ Links ]

21. Acevedo JC, Amaya A, Casasola O de L, Chinchilla N, De Giorgis M, Flórez S, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of neuropathic pain: consensus of a group of Latin American experts. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother 2009;23(3):261-81. DOI: 10.1080/15360280903098572. [ Links ]

22. Flórez Beledo J. Farmacología clínica. 6.a ed. Elsevier Masson; 2014. [ Links ]

23. Avellanal M, Díaz-Reganon G, Orts A, Soto S. Tapentadol vs. pregabalina asociada a otros opioides en dolor crónico: análisis de coste-efectividad. Rev Soc Esp Dolor 2014;21(2):84-8. [ Links ]

24. Casale R, Symeonidou Z, Bartolo M. Topical Treatments for Localized Neuropathic Pain. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2017;21(3):15. DOI: 10.1007/s11916-017-0615-y. [ Links ]

25. Pickering G, Martin E, Tiberghien F, Delorme C, Mick G. Localized neuropathic pain: an expert consensus on local treatments. Drug Des Devel Ther 2017;11:2709-18. DOI: 10.2147/DDDT.S142630. [ Links ]

26. Allegri M, Baron R, Hans G, Correa-Illanes G, Mayoral Rojals V, Mick G, et al. A pharmacological treatment algorithm for localized neuropathic pain. Curr Med Res Opin 2016;32(2):377-84. DOI: 10.1185/03007995.2015. 1129321. [ Links ]

27. de León-Casasola OA, Mayoral V. The topical 5 % lidocaine medicated plaster in localized neuropathic pain: a reappraisal of the clinical evidence. J Pain Res 2016;9:67. DOI: 10.2147/JPR.S99231. [ Links ]

28. Attal N, de Andrade DC, Adam F, Ranoux D, Teixeira MJ, Galhardoni R, et al. Safety and efficacy of repeated injections of botulinum toxin A in peripheral neuropathic pain (BOTNEP): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol 2016;15(6):555-65. DOI: 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)00017-X. [ Links ]

29. Rey R. Tratamiento del dolor neuropático. Revisión de las últimas guías y recomendaciones. Neurol Argent 2013;5(Supl. 1):1-7. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuarg.2011.11.004. [ Links ]

30. Mora Moscoso R, Guzmán Ruiz M, Soriano Pérez A, Alba-Moreno R de. Tratamiento del dolor neuropático central; futuras terapias analgésicas: revisión sistemática. Rev Soc Esp Dolor 2014;21(5):270-80. [ Links ]

31. Pavez Ulloa F. Agentes físicos superficiales y dolor: análisis de su eficacia a la luz de la evidencia científica. Rev Soc Esp Dolor 2009;16(3):182-9. [ Links ]

32. Mailis A, Taenzer P, Canadian Pain Society. Evidence-based guideline for neuropathic pain interventional treatments: Spinal cord stimulation, intravenous infusions, epidural injections and nerve blocks. Pain Res Manage 2012;17(3):150-8. [ Links ]

33. Cuenca González C, Flores Torres MI, Méndez Saavedra KV, Barca Fernández I, Alcina Navarro A, Villena Ferrer A. Síndrome doloroso regional complejo. Rev Clínica Med Fam 2012;5(2):120-9. [ Links ]

34. Finnerup NB, Attal N, Haroutounian S, McNicol E, Baron R, Dworkin RH, et al. Pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pain in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol 2015;14(2):162-73. DOI: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70251-0. [ Links ]

Received: March 16, 2018; Accepted: June 29, 2018

texto en

texto en