Introduction

Spinal infections are a rare cause of low back pain that can be distinguished depending on the specific compartment that they affect: vertebral body (osteomyelitis), intervertebral disc (discitis), epidural space or paravertebral region (abscesses)1. Cases of facet joint septic arthritis, which accounts for 4% of spinal infections with an incidence of 0.2-2/10,000 of overall hospital admissions2-3, have on rare occasions been reported as the cause of low back pain. To the authors’ knowledge, only four cases in children of facet joint septic arthritis, of probable haematogenous origin, have been previously published4 5 6-7.

Our aim is to present a new case in an otherwise healthy 13-year-old boy with an episode of acute lumbosciatalgia, limp and fever, initially treated in accordance with a low back and radicular pain standard management protocol without a noticeable improvement in his clinical condition. This case highlights the fact that a high degree of suspicion is required in the differential diagnosis of spinal infection to consider the possibility of facet joint infection. We also emphasize the complementary imaging study required to perform a correct differential diagnosis.

Caso clínico

A 13-year-old male patient admitted to a community hospital following two days of left lumbosciatalgia, lower lumbar back pain and limp which started after physical exertion, together with fever (38°C) in the previous 24 hours.

The physical examination revealed limp and a severe bilateral lumbar paravertebral muscle spasm predominantly on the left side, with pain upon application of pressure on the sciatic nerve and a left Straight Leg Raise Test positive (+) at 30º. He had no neurological deficit in the lower limbs, and no septic site was found that could clinically explain the concurrent fever (39.5°C). There was no change to the overlying skin’s appearance. Lumbar hyperextension performed in double stance was scarce and painful. Gatrointestinal, pulmonary, upper and lower airways and genitourinary infections were ruled out by the Pediatricians. The Rheumatology Department ruled out spondyloarthropathy and associated rheumatic diseases. The acute phase reactants of inflammation were elevated with an ESR (Eritrocite Sedimentation Rate) of 73 mm and CRP (C-Reactive Protein) of 11 mg/l. The blood culture, serology for brucellosis and antigen HLA-B27 blood test (to rule out inflammatory diseases of the spine) were all negative. A simple lumbosacral spine X-ray revealed no abnormalities, while the CT scan showed a slight narrowing of the L5-S1 disc space, disc protrusion at L3-L4 and L4-L5 and lumbosacral transitional anomalies with no other abnormalities. He was treated by paediatrician with NSAIDs (Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs), corticosteroids, benzodiazepines and cefuroxime (for 8 days), with improved low back pain, abatement of fever and normalized blood count, CRP and ESR. Following a positive Mantoux test and incomplete isoniazid treatment two years before, it was decided to reintroduce anti-tuberculosis chemoprophylaxis.

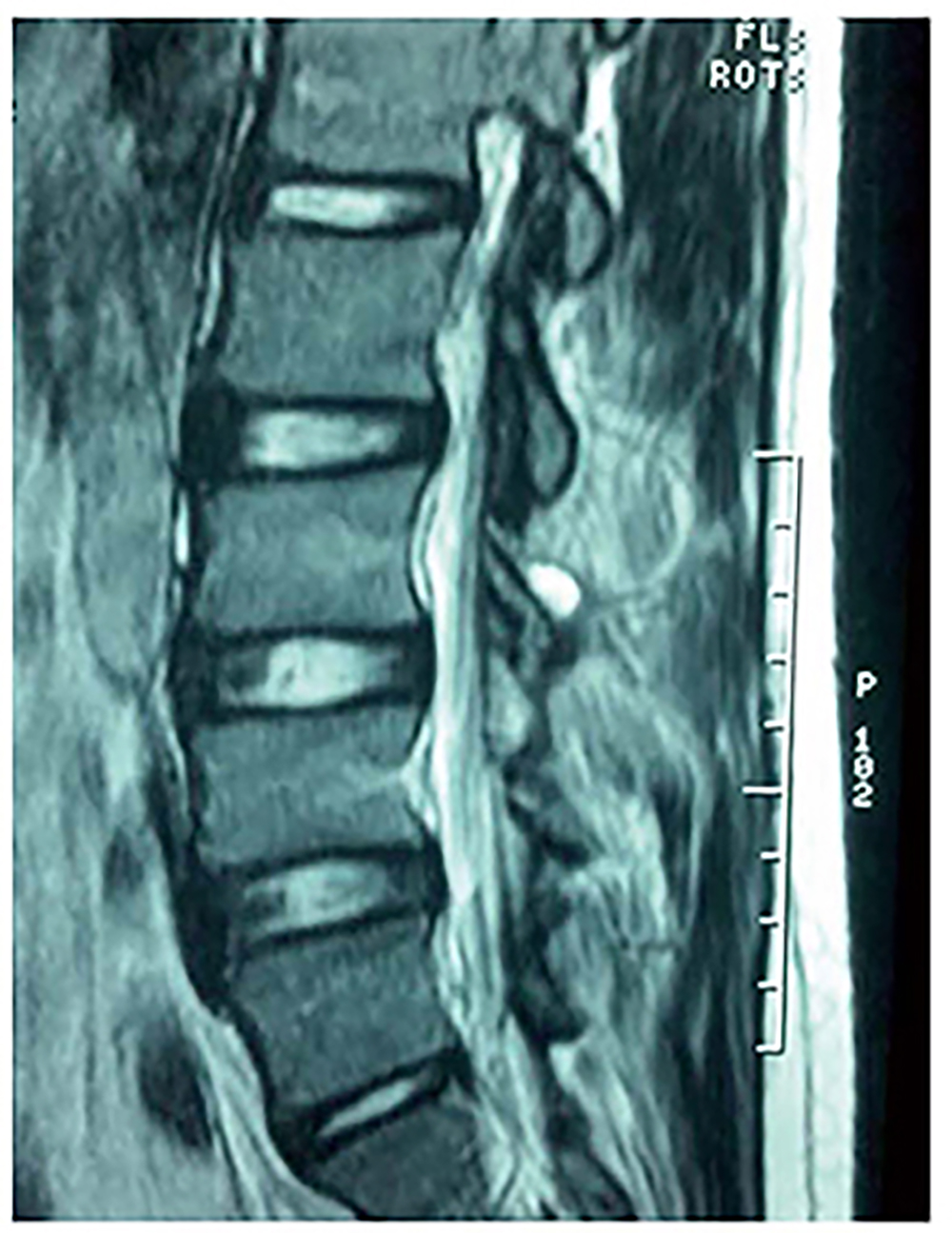

Three weeks later he was referred to opinion of our Pediatric Orthopaedic Service following a presumptive diagnosis of discitis. The patient reported low-intensity low back pain without fever, paravertebral muscle spasm upon fist percussion of the L2-S1 spinous processes and left irritated sciatic nerve symptoms. The Ga-67/Tc-99 scintigraphy revealed pathological hyperfixation of the radiotracer in the left L3-L4 hemivertebral region (Fig. 1). A lumbosacral magnetic resonance imaging scan (MRI) with gadolinium was ordered, which revealed a small amount of intra-articular fluid at the left L3-L4 interapophyseal joint (Fig. 2) due to facet joint abscess. Under the diagnosis of left L3-L4 lumbar interapophyseal septic arthritis, treatment was initiated with cefotaxime and cloxacillin (intravenous) for eight days. Given the patient’s rapid clinical improvement, he was discharged with cloxacillin (oral) on an outpatient basis for a further three weeks. He continued to improve with complete resolution of symptoms.

Figure 1. Ga-67/Tc-99 scintigraphy revealing pathological hyperfixation of the radiotracer in the left L3-L4 hemivertebral region

Figure 2. MRI revealing a small amount of intra-articular fluid at the left L3-L4 interapophyseal joint in sagital T2-weighted (A) and axial T2-weighted (B) images showing hyperintensity signal due to the facet joint abscess

The gadolinium MRI conducted one month later showed a significant reduction in fluid in the L3-L4 interapophyseal joint (Fig. 3) and the CT scan revealed sclerosis of the plates and interapophyseal joints at L3 with rarefaction of the L3-L4 left articular surface and some subchondral cystic lesions (Fig. 4), on the contrary to the initial CT scan.

Figure 3. Sagital T2-weighted image of MRI one month later showed a significant reduction in fluid in the left L3-L4 interapophyseal joint

Figure 4. Sagital CT-scan revealing sclerosis of the interapophyseal joints at L3 with rarefaction of the L3-L4 left articular surface and some subchondral cystic lesions

After intermittent rehabilitation spanning fifteen months, low back pain abated and the patient could resume normal life. The rehabilitation treatment was carried out due to the slight and intermittent paravertebral contracture. Four and a half years later, the patient continued to be asymptomatic.

Discussion

Most of cases of facet joint septic arthritis are believed to be haematogenous (72%)8, being epidural injection, acupuncture, joint surgery, penetrating wounds and the spread of adjacent sites of infection other reported sources of infection3 9.

Since 1987, only four cases of haematogenous interapophyseal infectious arthritis in paediatric patients have been published in the medical literature, three in lumbar spine: 18 month-old (right L4-L5), 8 year-old (left L5-S1), 10 year-old (left L4-L5)4 5-6 and one in thoracic spine: 8 year-old (left T11-12)7. The first patient presented with a septic pharyngeal infection and the third one with a positive urine culture, while no primary infection was present in the second patient. The origin of primary infection in the fourth patient, as well as their number of symptomatic days, were not reported.

Immunosuppression, intravenous drug addiction, diabetes mellitus, liver cirrhosis, kidney failure, neoplastic diseases and other chronic conditions have been reported as predisposing factors to haematogenous facet joint arthritis8. None of the paediatric cases published, including ours, found associated immunosuppressive factors.

The most-commonly isolated aetiological agent in adults is Staphylococcus aureus2; Escherichia coli was reported following urinary tract infection2, and methicillin resistant Staphylococus aureus was rarely reported10-11. The infection-inducing microorganism could not be isolated in two of the children while, from the other two, Staphylococcus epidermidis and Enterococcus faecalis were cultured from samples obtained from blood and urine cultures, respectively5-6.

A thorough both medical history and physical examination are essential in order to correctly diagnose patients with facet joint septic arthritis9. The patient reported regular acute pain of the affected vertebral segment accompanied by fever, pain upon palpation of the paravertebral muscles and spasm. Average symptom duration in the three cases prior to diagnosis was 5.3 days, and pain was not sciatic nor did it extend to the buttock or thigh. One of these cases presented with leg weakness, one episode of urinary incontinence and antalgic gait with plantar flexion6. The main symptom of the 18-month-old patient was limping4. Therefore, this diagnose has also to be included in the differential diagnose of limping in children.

The diagnostic process should include a differential white blood cell count, ESR, CRP and blood cultures8. All paediatric patients presented with high ESR levels.

Plain X-ray does not contribute with useful information to the initial diagnostic process of this condition, although some authors report expansion of the facet joint space or non-specific lytic or sclerotic changes in a sub-acute or chronic setting; this situation can be observed in the CT-scan after the recovery (Fig. 4). It may also go unnoticed in the CT scan, while scintigraphy is a sensitive but non-specific test; MRI was the confirmatory diagnostic test of facet joint septic arthritis in all paediatric cases reported. It is the most sensitive and specific of all the imaging tests used to diagnose this condition and the administration of gadolinium contrast medium reveals inflammatory and/or infectious changes and the formation of abscesses9. Interapophyseal punction for bacterial culture was not performed due to the fact that antibiotics were previously given by paediatrician and for the good response to cefotaxime and cloxacillin.

Two children presented with an extradural mass from the lower thoracic area to the sacrum with maximum L4-L5 thecal compression6 and in T11-127 for epidural abscess. Other adult patients reported complications are meningoencephalitis without fever or risk factors12, paraspinal abscess13, progressive quadriplegia14 and generalized infection15. Our patient’s condition took more than one month to be diagnosed, as reported for adults9 16,and the working diagnosis was infectious discitis or acute vertebral osteomyelitis until the interapophyseal source of the infection was identified.

The administration of systemic antibiotics, conservative theraphy, was curative in all four paediatric patients, and all recovered normal functionality without sequelae.

At the end of the process, physical treatment was carried out in our patient in order to eliminate the slight and intermittent residual paravertebral contracture.

The conclusion to be drawn from this process is that a high degree of suspicion is needed for early diagnosis of facet joint infection in patients presenting with spinal infection (acute low back pain, fever and/or intense pain upon palpation of the paravertebral muscles, with or without a limp, together with increased levels of acute phase reactants of inflammation). Unilateral involvement and symptom progression in fewer than four weeks helps to differentiate it from infectious spondylodiscitis3; blood cultures are required but a gadolinium MRI must be carried out to confirm the diagnosis.