Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista de Psicología del Trabajo y de las Organizaciones

versión On-line ISSN 2174-0534versión impresa ISSN 1576-5962

Rev. psicol. trab. organ. vol.29 no.2 Madrid ago. 2013

https://dx.doi.org/10.5093/tr2013a8

The push and pull factors related to early retirees' mental health status: A comparative study between Italy and Spain

Los factores que empujan y atraen a la jubilación anticipada y sus relaciones con la salud mental: un estudio comparativo entre Italia y España

Alessia Negrinia, Chiara Panarib, Silvia Simbulac y Carlos María Alcoverd

aInstitut de recherche Robert-Sauvé en santé et en sécurité du travail, Canada

bUniversità di Parma, Italy

cUniversità di Milano Bicocca, Italy

dUniversidad Rey Juan Carlos, Spain

ABSTRACT

In recent years, early retirement has attracted increasing attention in the literature. Using a larger Italian-Spanish sample, this study examines the push and pull factors related to early retirees´ mental health status, as well as the moderating effects of perceived self-efficacy on the relationships between reasons for early retirement and mental health. Analyses revealed that poor retirees´ mental health is positively correlated to the push factor Pressure from Employer and negatively related to the pull factor Pursue Own Interests. Thus, mental health status is better for Italian retirees than for their Spanish counterparts. The Italian sample shows that Pursue Own Interests was negatively related to poorer mental health particularly under the low self-efficacy condition. Findings suggest that mental health depends on both the motivating reasons that lead people to retire early and the personal resources available to them to manage this psychosocial transition.

Key words: Early retirement. Motivation. Self-efficacy. Personal resources. Mental health.

RESUMEN

El interés por el estudio de la jubilación anticipada se ha incrementado en los últimos años. Utilizando una muestra ítalo-española este estudio examina los factores que empujan y atraen a la jubilación anticipada y sus relaciones con la salud mental, así como los efectos moderadores de la auto-eficacia en dichas relaciones. Los resultados muestran una relación positiva entre los peores niveles de salud mental y el factor de empuje Presión del Empleador y una relación negativa con el factor de atracción Perseguir Intereses Propios. Así, el estado de salud mental es mejor para los jubilados italianos que para sus homólogos españoles. En la muestra italiana Perseguir Intereses Propios se relaciona negativamente con los peores niveles de salud mental en la condición de baja auto-eficacia. Los resultados sugieren que la salud mental depende de las razones que motivan hacia la jubilación anticipada y los recursos personales para afrontar esta transición psicosocial.

Palabras clave: Jubilación anticipada. Auto-eficacia. Motivación. Recursos personales. Salud mental.

Countries all over the world are facing unprecedented, and in many cases not fully predictable, demographic changes (The Economist, 2012; van der Heijden, Schalk, & van Veldhoven, 2008). The percentage of the world population in 2011 aged 60 years and over reached 11.2%, and is expected to reach 22% in 2050 (United Nations, 2011). Within the European Union (EU), the number of young people (here defined as 25-39-year-olds) has started to decrease. In the EU-27, projections for the next 50 years indicate that the percentage of older people will increase gradually, and not only in the segment between 65 and 79 years, but especially in the group of more than 80 years and both groups of age can reach 30% of the global population (European Commission, 2012). Thus, relevant institutions like the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) have highlighted the criticality of an aging population and the risks and costs of retirement in OECD countries (OECD 2006, 2007). Specifically, the rate of employability of EU workers within the age range of 55-64 was 43.5% (+3.9% in 2011). However, the participation and retirement rates among older workers differ between European countries. The legal retirement age varies from country to country, but it is generally around 60. This eligible age can vary depending, for example, on the gender, the occupational sector, or the contribution plans.

For instance, in 2006 Italy was characterized as having one of the weakest rates of employment of residents aged 55 and over (32.5%), in comparison to 44.1% for Spain. Italy has since increased the rates in 2011 of working people aged 55-64 and over (+5.4%), whereas Spain demonstrates an increase of only 0.4% (OECD, 2011).

Although demographic trends imply an increase in participation rates of older employees, a concurrent trend of early retirement is visible during the last decades, overall worldwide (OECD, 2008). Since the 1990s, many organizations have implemented early retirement practices as a strategy to reduce personnel and costs, in order to cope with the contingencies of the labor market (Armstrong-Stassen, 2004; Beehr, Glazer, Nielson, & Farmer 2000; Feldman, 1994; Szinovacz & Davey, 2005). This ´early retirement trap´ has been particularly extensive in some Southern and Central European countries (Angelini, Brugiviani, & Weber, 2009). At the time of this study, the Spanish job market was characterised by organizations which offered explicit pension benefits, incentives, and other financial solutions to encourage workers to retire at the age of 55 or earlier (Alcover, Crego, Guglielmi, & Chiesa, 2012). Pre-retirement plans were used to push Spanish employees to exit from the labor market before the established retirement age, thus having a significant impact on European societies on multiple levels (von Nordheim, 2003). According to OECD (2005), Spaniards retired on average three years before the mandatory retirement age (62 vs. 65). However, in 2011 the average retirement age has risen to 63 years due to the impact of measures established in recent years to prolong working life (Pacto de Toledo, 2012). Compared to Spanish context, at that time of this study, Italy was trying to extend the working life of its residents by focusing on retaining people aged 55 and over in the labor market. Several interventions, such as pension system reforms, were devised to change working conditions in order to retain workers aged 55 and over in the labor market and to promote their active participation at work and knowledge transfer to younger workers. OECD (2005) reported that Italians retired three years before the legal retirement age (57 vs. 60).

These two approaches to retirement and the perceived value of older workers demonstrate and provoke the need to study early retirement, its determinants and effects in work and organizational psychology.

Despite the wide diffusion of early retirement plans across European countries, only a partial knowledge exists of the psychological condition of early retirees who are forced to conclude their working life sooner than expected. Our study aims to contribute to the knowledge about such specific social groups who have experienced the work-retirement transition. Thus, we considered the reasons for early retirement as well as mental health status experienced in the post-retirement life. Within this framework, two samples of Italian and Spanish early retirees have been comparatively studied.

Theoretical background

Early retirement

In this current study, early retirement is considered as a typology of exit from the labor market before retirement age, as defined by the legislation (Blau & Gilleskie, 2003; Hansson, Koekkoek, Neece, & Patterson, 1997; Kim & Feldman, 2000; van der Heijden et al., 2008). In particular, early retirement is an individual´s development and change as ´an exit from an organizational position or career path of considerable duration, taken by individuals after middle age, and taken with the intention of reduced psychological commitment to work thereafter´ (Feldman, 1994, p. 287).

According to theoretical models proposed by Beehr et al. (2000), Davis (2003), Feldman (1994), and Shultz, Morton, and Weckerle (1998), early retirement is a psychosocial process that can be determined by different factors (e.g., social norms, working conditions, demographic factors, marital status, incentives, and pension systems) and likewise can produce different outcomes (e.g., stress, mental health problems, general health, life satisfaction).

Reasons for early retirement and effects on mental health status

Research on the determinants of early retirement is fragmented and an articulation of different levels of analysis exists (i.e., personal, interpersonal, organizational, and social) (Crego, Alcover, & Martínez-Íñigo, 2008).

A categorization of these motivating reasons can be described in terms of push and pull factors that influence older workers´ decisions to retire (Feldman, 1994; Hanisch, 1994; Hardy & Quadagno, 1995; Shultz et al., 1998; Taylor & Shore, 1995). Push factors have been defined as negative considerations that induce older workers to retire before the legal age like, for example, stressful working conditions (Henkens & Tazeelar, 1997), excessive workload, low wages (Kim & Feldman, 1998), health concerns, work changes, and work pressure (McGoldrick & Cooper, 1994). Conversely, pull factors are typically positive considerations that attract older workers toward retirement (Shultz et al., 1998). Free time, leisure activities, unpaid volunteer work, and family support can all lead to voluntary withdrawal from the labor force in order to pursue personal interests (e.g., McGoldrick & Cooper, 1994). Individuals forced to retire by push factors appear to have generally lower self-ratings of physical and emotional health and lower retirement and life satisfaction (Shultz et al., 1998). Older workers who perceive their retirement as forced are at risk of long-term effects on post-retirement well-being and health (Henkens, van Solinge & Gallo, 2008; van Solinge & Henkens, 2007). On the other hand, people for whom retirement was a voluntary choice tend to feel better after retirement (van Solinge, 2007), perceiving high levels of satisfaction with retirement and psychological well-being (Potöcnik, Tordera, & Peiró, 2008). These findings are supported by results of several recent Italian-Spanish studies in which the perception of voluntary retirement choice moderates the relation between work satisfaction and retirement satisfaction (Chiesa, Negrini, Crego, & Alcover, 2009), being as well associated to positive outcomes of early retirement, in opposition to involuntary retirement (Alcover et al., 2012; Fernández, Alcover, & Crego, 2010, 2013).

In this current study, Pressure from Employer and Pursue Own Interests were considered. The first variable represents a push factor, which defines a transition in which people are forced to retire. The second variable represents a pull factor that refers to a voluntary choice to retire. Previous studies have showed that these reasons for retirement are determinants of post-retirement adjustment, life satisfaction, and well-being (Shultz et al., 1998; Topa, Moriano, Depolo, Alcover, & Morales, 2009).

In this study, Mental Health Status is taken into consideration as the individual´s mental state or psychological well-being after retirement. Prior research has shown the existence of different subgroups of retirees, who suffer different consequences on their health (Wang, 2007), although there is evidence of increased prevalence of mental disorders in early retirees (generalized anxiety disorders and depressive disorders) compared to those who continue to work in the same age groups (Buxton, Singleton, & Melzer, 2005). There is also some evidence suggesting that the adverse effects of retirement on mental health (in particular, depression) may be larger in the event of involuntary retirement (Dave, Rashad, & Spasojevic, 2006). We are able to assess if early retirees, depending on their reason for retirement, have experienced a particular symptom (e.g., psychological distress) or behavior (e.g., unsocial behavior) in their post-retirement life.

Perceived Self-Efficacy

Bandura (1977) situates self-efficacy within a social cognitive theory that operates with other socio-cognitive factors in regulating human well-being and attainment. According to Bandura´s perspective (Bandura, 1997), self-efficacy beliefs influence the choices people make, their effort and persistence in accomplishing goals, their thought processes, and their emotional reactions. In addition, self-efficacy predicts confidence in own ability to deal with new changes. Personal feelings of competence have a primary influence on an adult´s reaction to life transitions and implications for retirement preference and retirement decisions (Barnes-Farrel, 2003). In this context, self-efficacy can be seen as a factor that helps employees feel comfortable when they make a retirement decision and enhances post-retirement adjustment (Adams & Beehr, 2003; Taylor-Carter, Cook, & Weinberg, 1997). Self-efficacy is one of the behavioral predispositions that lead people to engage in proactive strategies for mastering role changes inherent in retirement transition (Taylor-Carter & Cook, 2005). In contrast, older workers who have little confidence in their ability to cope with change in life constitute a clear risk group in terms of health (van Solinge, 2007). Furthermore, self-efficacy appears to be important in the adjustment of older adults with pain, moderating the effect of poor health (Turner, Ersek, & Kemp, 2005).

In a similar vein, a sense of mastery or personal control may well be a key psychosocial resource for well-being in retirement. For example, Kim and Moen (2002) found that, during the transition to retirement, a greater sense of mastery was predictive of higher morale for men and less depressive symptoms for both men and women. Donaldson, Earl, and Muratore (2010) found that, after controlling for the effects of demographics and health, a higher personal sense of mastery and more favorable conditions of exit significantly predicted adjustment to retirement.

Acknowledging these premises, perceived self-efficacy has been retained, in this paper, to be a core aspect in retirees´ mental health status. Specifically, this paper tested the hypotheses that self-efficacy moderates the relationship between reasons for early retirement and retirees´ mental health status.

Objectives and hypotheses

The present study is part of a larger research project involving the University of Bologna (Italy) and the Universidad Rey Juan Carlos in Madrid (Spain). This cross-European research project aims to investigate the experience of retirement in the Italian and Spanish early retirees and to contribute to the knowledge of the psychosocial transition "work-retirement" of these two specific social groups.

The three main objectives of this study were: (a) To measure the relationships between different reasons for early retirement (Pressure from Employer, Pursue Own Interests) and the mental health of early retirees; (b) to explore differences between Italian and Spanish early retirees; and (c) to assess the moderating effect of Perceived Self-Efficacy on the relationships between reasons for early retirement and retirees´ mental health.

Specifically, the present study sought to test the following hypotheses:

H1: Poor Mental Health Status will be positively related to early retirement due to the push factor Pressure from Employer, whereas it will be negatively related to early retirement motivated by the pull factor Pursue Own Interests.

H2: Italian and Spanish retirees differ in their reasons for early retirement (Pressure from Employer, Pursue Own Interests) and resulting Mental Health Status.

On the basis of the different existing social and legal situations of these two countries, we hypothesized that the Spanish sample would have higher Pressure from Employer scores and a poorer mental health status than the Italian sample. Pursue Own Interests is hypothesized to have a higher score in the Italian sample corresponding to a better Mental Health Status.

H3: The relationship between early retirement owing to the Pressure from Employer push factor and Mental Health Status will be moderated by Perceived Self-Efficacy.

H4: The relationship between early retirement derived from the Pursue Own Interests pull factor and Mental Health Status will be moderated by Perceived Self-Efficacy.

All hypotheses were tested separately on two samples consisting of Italian and Spanish early retirees.

Method

Participants and procedure

The Italian sample. The Italian sample consisted of individuals who belonged to one of the major Italian retirees´ unions. Every retiree registered with the Union for at least two years received a paper-and-pencil questionnaire by post. Enclosed with the questionnaire there was a letter briefly explaining the general aim of the study and emphasizing the confidentiality and anonymity of the answers. Participants took part in this study voluntarily. Data were analyzed exclusively by the research team.

The Italian sample was composed of 548 retirees. Fifty-five per cent of respondents were male. The age range was between 50 and 65 (M = 58.4, SD = 2.6). Of all the participants, 48.8% had a junior high school qualification, 44.5% a high school qualification, and 7.3% a university degree. Before retirement, most participants (73.3%) worked in the private sector (e.g., industries, commercial enterprises).

The Spanish sample. The Spanish participants belonged to four major Spanish early retirees´ associations. They received the Spanish version of the same questionnaire and a cover letter. Participants chose voluntarily to take part in the study. The questionnaire was administered by Spanish researchers following the same procedure used by Italian researchers (see description above).

The Spanish sample consisted of 566 participants, of whom 81.5% were male, and the age range was between 50 and 70 (M = 60.2, SD = 4.6); some 16% had a high school degree, 47.4% had a bachelor´s degree, and 36.6% had a professional degree. Before retirement, all participants worked in the private sector (e.g., communications industry, banks).

Measures

The same questionnaire was administered to both samples in their respective languages. Italian and Spanish participants answered a battery of questionnaires, including socio-demographic variables and the measures of Retirement Satisfaction Inventory (Floyd et al., 1992), Perceived Self-Efficacy (Borgogni, Petitta & Steca, 2001) and Mental Health Status (Goldberg, 1992) used in this paper. In order to guarantee coherence and validity of the questions, all items were translated utilizing a standard translation-back-translation procedure (Brislin, 1980). The internal consistency for both the samples is presented in Table 1.

Socio-demographics. Participants indicated gender, age, level of education, and the sector where they worked before retirement.

Reasons for early retirement. A reduced and adjusted version of the Retirement Satisfaction Inventory (Floyd et al., 1992) was used to measure the reasons for retirement. The reasons considered were: Pressure from Employer (two items, e.g., "I was pressured to retire by my employer"), and Pursue Own Interests (four items, e.g., "I wanted more time to pursue my interests, such as hobbies and travel"). Responses were provided on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 ("very unimportant") to 7 ("very important").

Perceived Self-Efficacy was measured by eight items of the Perceived Self-Efficacy Scale adapted to retirement (Borgogni et al., 2001). The items referred to perception of one´s competences and beliefs about one´s ability to cope with difficulties and achieve goals in retirement (e.g., "Master unexpected events of retirement"). Participants answered on a seven-point scale ranging from 1 ("not able at all") to 7 ("completely able"). Thus, higher scores indicated higher perceived self-efficacy status.

Mental Health Status was evaluated by the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12, Goldberg, 1992). Each item was rated on a four-point scale, in which higher scores indicated a more poorly perceived mental health status. We used a modified scoring method, called Goodchild and Duncan-Jones´s method (CGHQ), as it demonstrated superior construct validity and greater sensitivity with respect to the traditional scoring method of GHQ (Whaley, Morrison, Payne, Fritschi, & Wall, 2005). On the basis of this method, the scoring of negative items, such as "feeling unhappy and depressed" is 0, 1, 1, 1. The scoring of positive items, such as "been able to concentrate on whatever you´re doing" is 0, 0, 1, 1.

Results

The statistical package SPSS 18.0 was used for all analyses. Descriptive statistics, correlations among variables, and alpha coefficients were separately computed for both samples. Results are presented in Table 1.

Inter-correlations between variables

As reported in Table 1, poor Mental Health Status was found to be positively related to early retirement owing to the push factor Pressure from Employer in both the Italian (r = .13, p < .01) and Spanish samples (r = .18, p < .01). In support of H1, as reported in Table 1, early retirement owing to the pull factor Pursue Own Interests was found to be negatively correlated with poor Mental Health Status in both the Italian (r = -.16, p < .01) and Spanish samples (r = -.18, p < .01).

Hypothesis 1 was thus supported by the analyses.

Group differences

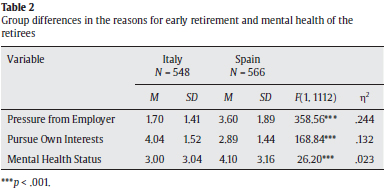

A multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was performed to verify H2. Country (i.e., Italy, Spain) was assumed as an independent variable and two reasons for early retirement (i.e., Pressure from Employer, Pursue Own Interests) and Mental Health Status were assumed as observed variables. An overall significant multivariate effect of the country was found, Wilks´ λ = 0.70, F(3, 1110) = 157.33, p < .001, partial η2 = .30]. As shown in Table 2, subsequent univariate analysis of variance (ANOVAs) indicated that the two country groups differed significantly in early retirement owing to Pressure from Employer, F(1, 1112) = 358.56, p < .001, partial η2= .24 and to Pursue Own Interests, F(1, 1112) = 168.84, p < .001, partial η2= .13; and in Mental Health Status, F(1, 1112) = 35.03, p < .001, η2 = .02).

Specifically, Italian respondents seemed to retire before the legal age in order to Pursue Own Interests (M = 4.04, SD = 1.52 vs. M = 2.89, SD = 1.44), whereas Spanish respondents tended to retire before the legal age because of Pressure from Employer (M = 3.60, SD = 1.90 vs. M = 1.70, SD = 1.41). With regards to Mental Health Status, Italian respondents showed better levels of mental health (M = 3.00, SD = 3.04) than Spanish respondents (M = 4.10, SD = 3.16), although in this case the effect size associated with the univariate F test was small. Thus, Hypothesis 2 was supported by the analyses.

Interaction effects

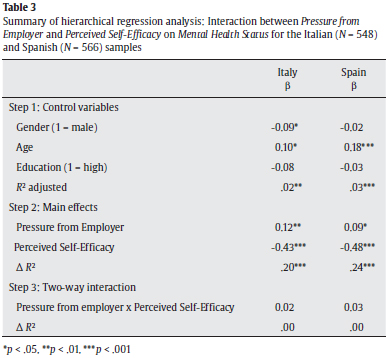

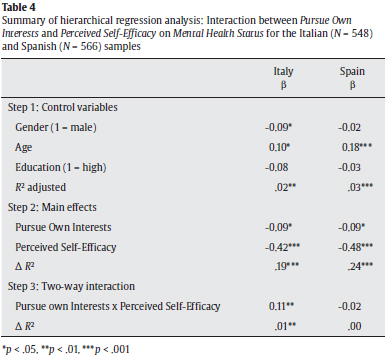

To test the proposed effects of pull and push factors (Pressure from Employer and Pursue Own Interests, respectively) and Perceived Self-Efficacy on Mental Health Status (H3), a series of hierarchical moderated regressions were used separately for the two samples. Control variables (i.e., gender, age, and education) were introduced during step 1. In step 2, the main effects of independent variables (Pressure from employer or Pursue Own Interests) and the moderator (Perceived Self-Efficacy) were tested. In step 3, the 2-way interaction of Pressure from Employer or Pursue Own Interests and Perceived Self-Efficacy was examined. All variables were mean-centered prior to computing the interaction terms (see Aiken & West, 1991).

Italian sample

As can be seen in Table 3, gender and age were significant predictors of mental health, with female and older employees reporting themselves as having poorer mental health status. Pressure from Employer had a positive main effect on poor Mental Health Status, whereas Self-Efficacy had a negative main effect on poor Mental Health Status. This suggests that perceptions of high self-efficacy could have a positive effect on perception of a better Mental Health Status. However, the two-way interaction was not significant, meaning that H3 was not supported for the Italian sample.

As far as the pull factor was considered (Table 4), it is possible to note that both Pursue Own Interests and Self-Efficacy had a negative effect on poor Mental Health Status. Moreover, the increase of the variance explained by the interaction terms was significant for Pursue Own Interests x Perceived Self-Efficacy (β = .11, p < .01). In order to test the significance of each slope, a simple slope analysis was performed (Aiken & West, 1991).

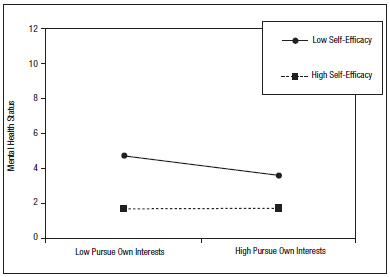

Figure 1. Interaction between Pursue Own Interests and Perceived Self-Efficacy

on Mental Health Status for the Italian sample.

Note. Labels "Low" and "High" refer to 1 SD below the mean and to 1 SD above the mean, respectively.

Simple slopes analysis revealed that the negative effect of Pursue Own Interests on poor Mental Health Status was more marked for employees who were less self-efficacious (β = -0.19, p < .01), than for those employees who were more self-efficacious (β = 0.01, p = .88, ns). Italian sample partially supported H4.

Spanish sample

As can be seen in Table 3, only age was a significant predictor of mental health, such that male employees reported themselves as having poorer mental health. Pressure from Employer had a positive main effect on Mental Health Status, whereas Perceived Self-Efficacy had a negative main effect on Mental Health Status. This suggests that, as much as the Italian sample, the perceptions of high self-efficacy could have a positive effect on perceiving better mental health. However, the two-way interaction was not significant, meaning that H3 was not supported for the Spanish sample.

As far as the pull factor was considered (Table 4), it is possible to note that both Pursue Own Interests and Perceived Self-Efficacy had a negative effect on mental health. However, the two-way interaction was not significant, meaning that H4 was not supported for the Spanish sample.

Discussion

The first goal of this study was to examine the relationship between reasons for early retirement and mental health status. According to the first hypothesis, the push factor Pressure from Employer was positively related to poor mental health status whereas the pull factor Pursue Own Interests was negatively associated with it.

This study demonstrates that the experience of forced early retirement represented a difficult psychosocial transition compared to that experienced by individuals who exit voluntarily to pursue their own interests. Our results support the conclusions of prior studies that suggest the existence of differences in post-employment life depending on the level of voluntariness concerned in retirement from the labor market (Alcover et al., 2012; Crego et al., 2008; Fernández et al., 2010, 2013; Isaksson & Johansson, 2000; Reitzes & Mutran, 2004; Shultz et al., 1998).

With regard to the push factors, Siegrist, Wahrendorf, von dem Knesebeck, Juürges, and Börsch-Supan (2006) have pointed out that the exposure to poor quality of work, in combination with pressure from employers, often reduces performance and motivation at earlier stages of employment trajectories, thus inducing individuals to leave the labor force before the legal retirement age. Conversely, pull factors, attracting individuals to engage in post-retirement activities, have an impact on their retirement adjustment and satisfaction (Price, 2003). Voluntary retirement gives retirees a sense of control that non-voluntary retirees may not perceive (Kimmel, Price, & Walker, 1978). According to Noone, Stephens, and Alpass (2009), our results confirmed the importance of the pre-retirement phase, during which people experience their transition from work to retirement. The way people experience this phase (forced vs. voluntary retirement) has significant impact on their mental health status after their exit from work life. This is in line with the second result of this inquiry, which concerns the differences between Italian and Spanish retirees. The two samples differed with respect to the presence of push and pull factors. In Spain the push factor, Pressure from Employer, was prevalent and had the highest score among reasons for early retirement, whereas in Italy the pull factor of Pursue Own Interests was the most important aspect that urged workers to exit early. These findings confirm that the two countries under consideration seem to differ substantially in employment opportunities for and perceived value of older workers.

In fact, within the Spanish context retirement choice was regulated by strong incentives to retire early (Boldrin, Jiménez-Martín, & Peracchi, 1997). Companies have cut high salary expenses and replaced senior people with younger, cheaper personnel. Compared with the Spanish situation, the Italian ratio of forced retirement is relatively low and early exits from the labor force have not been promoted by public policies.

The human cost of the Spanish "formula" for retirement also has an impact on the personal life of each employee who retires early (Alba, 1997) and our findings support negative outcomes of forced retirement. In fact, the Spanish sample showed a worsened mental health status because the perception of being forced to retire probably prevailed among the participants. Van Solinge and Henkens (2007) found that the perception of voluntary vs. non-voluntary retirement is not completely at the mercy of retirement circumstances such as mandatory retirement age, early retirement incentives or related health issues. The difference seems to lie also in the resources available for retirement.

In this study, Perceived Self-Efficacy, as a personal resource, has been studied. A third significant result showed that self-efficacy moderated the effect of the pull factor Pursue Own Interests by diminishing the risk of poor mental health of Italian retirees. Specifically, our results confirm that retirees´ Mental Health Status may be enhanced if individuals have the belief that they can perform certain behaviors and cope with transition. According to Bandura´s Social Learning Theory (1977), self-efficacy is a motivational construct that relates to a specific task. Empirical evidence that self-efficacy might be an important predictor of the ability to adjust successfully to retirement comes from the work of Taylor and Shore (1995). Also, Barnes-Farrel (2003) showed that higher self-efficacy was associated with lower pre-retirement anxiety. Our findings corroborate these theories and provide further evidence of the importance of considering self-efficacy, as done in this study, when addressing mental health status of early retirees. Our results also confirm the assertion that a sense of mastery or personal control may be a key psychosocial resource for mental health in retirement (Donaldson et al., 2010). In fact, when some adverse organizational aspects cannot be avoided -and therefore lead to people leving the labor force- the feeling of personal control over the transition could help individuals maintain active lifestyles and nourish personal self-concepts to counter the loss of former professional roles.

A last consideration needs to be made with regard to the fact that self-efficacy has no moderating role in the relationship between reasons for retirement and Spanish participants´ mental health. This difference probably lies in the social, legal, and economic contexts of forced retirement of each of the two countries. Spanish participants have a higher score for the Pressure from Employers than Italians and the average score for Pursuing Own Interests is very low. The Spanish retirees perceive their exit from work as forced and this is justified by the historical labor force change of the last years (Gómez & Martí, 2003; UGT, 2001). It is thus possible to conclude that the institutionalization of early retirement observed in the Spanish case could set disincentives for the continued education and motivation of older workers rather than viewing them as a key resource in an economy affected by population ageing, with lifestyle consequences after exit from the labor force.

Study Limitations

The results of this study must be interpreted in the light of certain limitations that raise issues for future research.

The cross-sectional design does not allow us to establish the direction of relations between reasons for early retirement and mental health status. If the retirement decision implies a long-term sequential process within the lifespan (Settersten, 2003), longitudinal studies are then necessary to describe and explain their complex pathways and the consequences of early retirement. Another important limitation of our study refers to the retrospective nature of the data, so it will be necessary to replicate the results in prospective studies with extensive follow-up over the years (Schuring, Robroek, Otten, Arts, & Burdorf, 2013).

This comparative study has led to an exploration of the differences in the Italian and Spanish socio-economic contexts, which have experienced very different labor force changes over the last few years. A limitation of our study concerns the different sociodemographic characteristics of the Spanish and Italian samples, particularly with regard to gender, since 82% were male in the Spanish sample compared to 55% in the Italian sample. This study is one of the first attempts to explore how various reasons for retirement can influence early retirees´ mental health status in the time following their exit from the workforce. Despite this, the comparison between Italy and Spain requires future research to study the specific social, legal, and economic systems of these two European countries, as well as to consider the potential effects of cultural factors specific to each country.

Practical implications and future research

The results of our study support the concept of retirement as a process involving a variety of factors, in line with recent research (e.g., Pleau & Shauman, 2013; Shultz & Wang, 2011). In addition, we have found that the consequences for individuals can be very different depending on how the process unfolds. This has important practical implications since the effects on health can be very different depending on how people experienced retirement. Thus, future studies should explore the factors associated with work retirement which have positive and negative causal effects on the health of citizens (Coe & Zamarro, 2011), due to great transcendence for the European countries and their design of labor policies about later retirement ages. In this sense, our study has implications not only for the well-being of individuals and for retirement transition and adjustment (Wang & Shultz, 2010), but it also implies socio-political concerns (Topa, Alcover, Moriano, & Depolo, 2013). Population ageing is one of the most urgent challenges that is currently faced by both developed and developing countries (United Nations, 2011). The early retirees´ both objective and perceived health, especially their mental health status, is a matter of great importance, since it can have consequences for the quality of life of older people, as well as for the cost and viability of social protection systems.

Conclusion

To conclude, during the last decade figures of individuals involved in early retirement have grown in many European countries. Meanwhile, it has been well established that outcomes of motivations for early retirement affect personal, social, and organizational domains. Further studies can contribute to more in-depth research into the impact of early retirement (forced vs. voluntary) on the retirement adjustment process. We also anticipate that it will be possible to identify typologies of organizational exit as well as typologies of post-retirement adjustment which would be an important further nuance in determining the effects of motivational impacts on early-retirement as an important life transition.

Conflicts of interest

The authors of this article declare no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Adams, G. A., & Beehr, T. A (2003). Retirement: Reasons, Processes, and Results. New York: Springer. [ Links ]

2. Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple Regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

3. Alba, A. (1997). Labor force participation and transitions of older workers in Spain. Carlos III University Working Paper, No. 97-39. [ Links ]

4. Alcover, C. M., Crego, A., Guglielmi, D., & Chiesa, R. (2012). Comparison between the Spanish and Italian early work retirement models: A cluster analysis approach. Personnel Review, 41, 380-403. [ Links ]

5. Angelini, V., Brugiviani, A., & Weber, G. (2009). Ageing and unused capacity in Europe: is there an early retirement trap? Economic Policy, 24, 463-508. [ Links ]

6. Armstrong-Stassen, M. (2004). The influence of prior commitment on the reactions of layoff survivors to organizational downsizing. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 9, 46-60. [ Links ]

7. Bandura, A. (1977). Social Learning Theory. New York: General Learning Press. [ Links ]

8. Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Freeman. [ Links ]

9. Barnes-Farrell, J. (2003). Beyond Health and Wealth: Attitudinal and Other Influences on Retirement Decision-Making. In G. A. Adams, & T. A. Beehr (Eds.), Retirement: Reasons, Processes, and Results (pp. 159-187). New York: Springer. [ Links ]

10. Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173-1182. [ Links ]

11. Beehr, T. A., Glazer, S., Nielson, N. L., & Farmer, S. J. (2000). Work and non-work predictors of employees´ retirement ages. Journal of Vocational Behaviour, 57, 206-225. [ Links ]

12. Blau, D. M., & Gilleskie, D. B., (2003). The role of retiree health insurance in the employment behavior of older men (Working Paper No. 10100). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. [ Links ]

13. Boldrin, M, Jiménez-Martín, S., & Peracchi, F. (1997). Social Security and Retirement in Spain. NBER Working Paper, No. 6136. [ Links ]

14. Borgogni, L., Petitta, L., & Steca, P. (2001). Efficacia percepita personale e collettiva nei contesti organizzativi. In G. V. Caprara (Ed.) La valutazione dell´autoefficacia. Trento: Erickson. [ Links ]

15. Brislin, R. W. (1980). Translation and content analysis of oral and written material. In H. C. Triandis & J. W. Berry (Eds.), Handbook of cross-cultural psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 389-444). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon. [ Links ]

16. Buxton, J. W., Singleton, N., & Melzer, D. (2005). The mental health of early retirees. National interview survey in Britain. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 40, 99-105. [ Links ]

17. Chiesa, R., Negrini, A., Crego, A., & Alcover, C. M. (2009). Il pensionamento come fase della carriera: il ruolo della soddisfazione lavorativa e della volontarietà del ritiro. Giornale Italiano di Psicologia dell´Orientamento, 10 (2), 3-18. [ Links ]

18. Coe, N. B., & Zamarro, G. (2011). Retirement effects on health in Europe. Journal of Health Economics, 30, 77-86. [ Links ]

19. Crego, A., Alcover, C. M., & Martinez-Ìñigo, D. (2008). The transition process to post-working life and its psychosocial outcomes. A systematic analysis of Spanish early retirees´ discourse. Career Development International, 13 (2), 186-204. [ Links ]

20. Dave, D., Rashad, I., & Spasojevic, J. (2006). The Effects of Retirement on Physical and Mental Health Outcomes. NBER Working Papers 12123. National Bureau of Economic Research. Retrieved July 16, 2013, from: http://www.nber.org/papers/w12123.pdf [ Links ]

21. Davis, M. A. (2003). Factors related to bridge employment participation among private sector early retirees. Journal of Vocational Behaviour, 63, 55-71. [ Links ]

22. Donaldson, D., Earl, J. K., & Muratore, A. M. (2010). Extending the integrated model of retirement adjustment: Incorporating mastery and retirement planning. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 77, 279-289. [ Links ]

23. European Commission (2012). EEO Review: Employment Policies to Promote Active Ageing 2012. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [ Links ]

24. Eurostat (2007). Statistics in focus. Populations and social conditions 97/2007 (24 luglio 2007). Retrieved January 16, 2013, from http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/cache/ITY_OFFPUB/KS-SF-07-097/EN/KS-SF-07-097-EN.PDF [ Links ]

25. Feldman, D. C. (1994). The decision to retire early: A review and conceptualization. Academy of Management Review, 19, 285-311. [ Links ]

26. Fernández, J. J., Alcover, C. M., & Crego, A. (2010). Percepciones sobre la voluntariedad en el proceso de salida organizacional en una muestra de prejubilados españoles. Revista de Psicología del Trabajo y de las Organizaciones, 26, 135-146. [ Links ]

27. Fernández, J. J., Alcover, C. M., & Crego, A. (2013). Psychosocial profiles of early retirees based on experiences during post-working life transition and adjustment to retirement. Revista de Psicología Social, 28, 99-112. [ Links ]

28. Floyd, F. J., Haynes, S. N., Doll, E. R., Winemiller, D., Lemsky, C., Burgy, T. M., ... Heilman, N. (1992). Assessing retirement satisfaction and perceptions of retirement experiences. Psychology and Aging, 7, 609-621. [ Links ]

29. Goldberg, D. (1992). General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12). Windsor, UK: NFER-Nelson. [ Links ]

30. Gómez, A., & Martí, C. (2003). Las prejubilaciones y su impacto en la persona en la empresa y en el sistema de pensiones. Documento investigación, Cátedra SEAT de Relaciones Laborales DI nº 522, Navarra. Retrieved January 16, 2013, from http://www.iese.edu/research/pdfs/DI-0522.pdf [ Links ]

31. Hanisch, K. A. (1994). Reasons people retire and their relation to attitudinal and behavioral correlates in retirement. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 45, 1-16. [ Links ]

32. Hansson, R. O, Koekkoek, P. D., Neece, W. M., & Patterson, D. W. (1997). Successful ageing at work: Annual Review, 1992-1996. The older worker and transitions to retirement. Journal of Vocational Behaviours, 51, 202-223. [ Links ]

33. Hardy, M. A., & Quadagno, J. (1995). Satisfaction with early retirement: Making choices in the auto industry. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 50B, S217-S228. [ Links ]

34. Henkens, K. , & Tazelaar, F. (1997). Explaining retirement decisions of civil servants in The Netherlands: intentions, behavior, and the discrepancy between the two. Research on Aging, 19(2), 139-173. [ Links ]

35. Henkens, K., van Solinge, H., & Gallo, W.T. (2008). Effects of retirement voluntariness on changes in smoking, drinking and physical activity among Dutch older workers. European journal of public health, 18, 644-649. [ Links ]

36. Isaksson, K., & Johansson, G. (2000). Adaptation to continued work and early retirement following downsizing: Long term effects and gender differences. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 73, 241-256. [ Links ]

37. Kim, J. E., & Moen, P. (2002). Retirement transitions, gender and psychological well-being: A life-course, ecological model. Journal of Gerontology, 57B, 212-222. [ Links ]

38. Kim, S., & F eldman, D. C. (1998), Healthy, wealthy, or wise: predicting actual acceptances of early retirement incentives at three points in time. Personnel Psychology, 51, 623-642. [ Links ]

39. Kim, S., & Feldman, D. C. (2000). Working in retirement: the antecedents of bridge employment and its consequences for quality of life in retirement. Academy of Management Journal, 43, 1195-1210. [ Links ]

40. Kimmel, D. C, Price, K. F., & Walker, J. W. (1978). Retirement choice and retirement satisfaction. Journal of Gerontology, 33, 575-585. [ Links ]

41. Lim, V. K. G. (2003). An empirical study of older workers´ attitudes towards the retirement experience. Employee Relations, 25, 330-46. [ Links ]

42. McGoldrick, A. E., & Cooper, C. L. (1994). Health and Ageing as Factors in the Retirement Experience. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 4(1), 1-20. [ Links ]

43. Noone, J. H., Stephens, C., & Alpass, F. M. (2009). Preretirement Planning and Well-Being in Later Life: A Prospective Study. Research on Aging, 31, 295-317. [ Links ]

44. OECD (2005). Pensions at a Glance. Retrieved January 24, 2013, from http://www.oecd.org/els/socialpoliciesanddata/pensionsataglance2005.htm [ Links ]

45. OECD (2006). Older workers: living longer, working longer. DELSA Newsletter No. 2. Retrieved January 16, 2013, from www.oecd.org/dataoecd/54/47/35961390.pdf [ Links ]

46. OECD (2007). Pensions at a glance. Public policies across OECD countries. Paris: OECD Pub. [ Links ]

47. OECD (2008). Labour Force Statistics. Paris: OECD Pub. [ Links ]

48. OECD (2011). Employment rate of older workers (% of population aged 55-64). Retrieved January 16, from http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/download/190600061e1t004.pdf?expires=1358374354&id=id&accname=freeCont ent&checksum=4D4C17A81ADBEB7804D21C401F6C9882 [ Links ]

49. Pacto de Toledo (2012). Informe sobre la situación de la jubilación anticipada con coeficiente reductor y de la jubilación parcial. Madrid: Ministerio de Empleo y Seguridad Social, Secretaría de Estado de Seguridad Social. Retrieved February 20, 2013, from http://www.cenavarra.es/documentos/ficheros_comunicacion/pactodetoledo.pdf [ Links ]

50. Pleau, R., & Shauman, K. (2013). Trends and correlates of post-retirement employment, 2013, 1977-2009. Human Relations, 66, 113-141. [ Links ]

51. Potöcnik, K., Tordera, N., & Peiró, J. M. (2008). Ajuste al retiro laboral en función del tipo de retiro y su voluntariedad desde una perspectiva de género. Revista de Psicología del Trabajo y de las Organizaciones, 24, 347-364. [ Links ]

52. Price, A. C. (2003). Professional women´s retirement adjustment: the experience of reestablishing order. Journal of Aging Studies, 17, 341-355. [ Links ]

53. Reitzes, D. C., & Mutran, E. J. (2004). The transition to retirement: Stages and factors that influence retirement adjustment. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 59, 63-84. [ Links ]

54. Schuring, M., Robroek, S. J., Otten, F. W., Arts, C. H., & Burdorf, A. (2013). The effect of ill health and socioeconomic status on labor force exit and re-employment: a prospective study with ten years follow-up in the Netherlands. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 39, 134-143. [ Links ]

55. Settersten, R. (2003). Invitation to the life course: The promise. In R. Settersten (Ed.), Invitation to the Life Course: Toward New Understandings of Later Life (pp. 1-12). Amityville, NY: Baywood Publishing Company. [ Links ]

56. Shultz, K. S., Morton, K. R., Weckerle, J. R. (1998). The Influence of Push and Pull Factors on Voluntary and Involuntary Early Retirees´ Retirement Decision and Adjustment. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 53, 45-57. [ Links ]

57. Shultz, K. S., & Wang, M. (2011). Psychological perspectives on the changing nature of retirement. American Psychologist, 66, 170-79. [ Links ]

58. Siegrist, J., Wahrendorff, M., von dem Knesebeck, O., Jürges, H., & Boörsch-Supan, A. (2006). Quality of work, well-being, and intended early retirement of older employees-baseline results from the SHARE Study. European Journal of Public Health, 17(1), 62-68. [ Links ]

59. Szinovacz, M. E., & Davey, A. (2005). Predictors of perceptions of involuntary retirement. The Gerontologist, 45(1), 36-47. [ Links ]

60. Taylor, M. A., & Shore, L. M. (1995). Predictors of planned retirement age: An application of Beehr´s model. Psychology and Aging, 10, 76-83. [ Links ]

61. Taylor-Carter, M. A., Cook, K., & Weinberg, C. (1997). Planning and expectations of the retirement experience. Educational Gerontology, 23, 273-288. [ Links ]

62. Taylor-Carter, M. A., & Cook, K. (2005). Adaptation to Retirement: Role Changes and Psychological Resources. Career Development Quarterly, 44(1), 67-82. [ Links ]

63. The Economist (2012). A New Vision for Old Age. Rethinking Health Policy for Europe´s Ageing Society. A Report for the Economist Intelligence Unit. Londres: The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited. Retrieved August 27, 2012, from http://www.managementthinking.eiu.com/sites/default/files/downloads/A new vision for old age_0.pdf [ Links ]

64. Topa, G., Alcover, C. M., Moriano, J. A., & Depolo, M. (in press). Bridge employment quality and its impact in retirement: A structural equation model with SHARE panel data. Economic and Industrial Democracy. [ Links ]

65. Topa, G., Moriano, J. A., Depolo, M., Alcover, C. M., & Morales, J. F. (2009). Antecedents and consequences of retirement planning and decision-making: A meta-analysis and model. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 75, 38-55. [ Links ]

66. Turner, J., Ersek, M., Kemp C. (2005). Self-Efficacy for Managing Pain Is Associated With Disability, Depression, and Pain Coping Among Retirement Community Residents With Chronic Pain. The Journal of Pain, 6, 471-479. [ Links ]

67. UGT. Federación de Servicios. Secretaría de Gabinetes Documentación y Estudios (2001). Introducción a las prejubilaciones. Madrid: UGT. Retrieved January 16, 2013, from http://fes.ugt.org/gabinetes/estudios/publica/estpreju.pdf [ Links ]

68. United Nations (2011). World Population Prospects. The 2010 Revision. Highlights and Advanced Tables. Working Paper no. ESA/P/WP.220. New York: UN, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. [ Links ]

69. Van der Heijden, B. J. M., Schalk, R., & van Veldhoven, J. P. M. (2008). Ageing and careers: European research on long-term career development and early retirement. Career Development International, 13(2), 85-94. [ Links ]

70. Van Solinge, H. (2007), Health change in retirement; a longitudinal study among older workers in the Netherlands. Research on Aging, 29, 2253-256. [ Links ]

71. Van Solinge, H., & Henkens, K. (2007). Involuntary retirement: the role of restrictive circumstances, timing, and social embeddedness. Journal of Gerontology, 62, S295-S303. [ Links ]

72. Von Nordheim, F. (2003). EU policies in support of member state efforts to retain, reinforce, and re-integrate older workers in employment. In H. Buck & B. Dworschak (Eds.), Ageing and Work in Europe: Strategies at Company Level and Public Policies in Selected European Countries (pp. 9-26). Stuttgart: Federal Ministry of Education and Research. [ Links ]

73. Wang, M. (2007). Profiling retirees in the retirement transition and adjustment process: examining the longitudinal change patterns of retirees´ psychological well-being. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 455-474. [ Links ]

74. Wang, M., & Shultz, K. S. (2010). Employee retirement: a review and recommendations for future investigation. Journal of Management, 36, 172-206. [ Links ]

75. Whaley, C. J., Morrison, D. L., Payne, R. L., Fritschi, L., & Wall, T. D. (2005). Chronicity of Psychological Strain in Occupational Settings and the Accuracy of the General Health Questionnaire. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 10, 310-319. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Alessia Negrini.

Institut de recherche Robert-Sauvé en santé et en sécurité du travail.

505 boul. de Maisonneuve Ouest. H3A 3C2 Montréal.

E-mail: alessia.negrini@irsst.qc.ca

Manuscript received: 19/03/2013

Revision received: 26/06/2013

Accepted: 30/06/3013