Introduction

As a result of increasing competition, higher dynamism, a stronger market-orientation, and continuous pressures towards efficiency and accountability, higher education institutions have experienced tremendous transformations worldwide in the last few decades (Aguinis, Shapiro, Antonacopoulou, & Cummings, 2014; Blaschke, Frost, & Hattke, 2014). Naturally, these changes have resulted in increasing work demands for academics in terms of scientific productivity, pedagogical training, permanent assessment, and innovation requirements (Watts & Robertson, 2011). Indeed, the increase in cognitive and emotional demands faced by today’s scholars on a daily basis along with increasing work overload, problematic schedules, work-family imbalance, and job insecurity have resulted in increasing strain (Fredman & Doughney 2012; Kinman & Jones 2008; Kinman, Jones, & Kinman, 2006; Salanova, Martínez, & Lorente, 2005; Shin & Jung 2014), all of which has contributed to turning the academic profession into one of the most stressful occupations. This scenario becomes even more complex when job resources such as social support from leaders and colleagues, opportunities for career development, and rewards are scarce, which increases the psychosocial risk factors that characterize the daily work experiences of academics (Kinman & Wray, 2013; Salanova et al., 2005). As psychosocial risks, these work-related factors, either by excess, defect, or combination, pose a threat to the physical, social, and/or psychological integrity of scholars (Meliá et al., 2006). This, in turn, has been found to be associated with several negative outcomes, including burnout, (Crawford, LePine, & Rich, 2010; Schaufeli, Maslach, & Marek, 2017), poor job performance, and inefficiency (Driskell & Salas, 2013; Schat, Kelloway, & Desmarais, 2005), and job dissatisfaction (Dierdorff & Morgeson, 2013; Rich, Lepine, & Crawford, 2010).

Surprisingly, in spite of the stress of leading a successful academic life, a number of studies show that most scholars are not burned-out, unmotivated, or dissatisfied, but rather tend to experience positive emotional states such as job satisfaction (Bentley, Coates, Dobson, Goedegebuure, & Meek, 2013; Hakanen, Bakker, & Schaufeli, 2006; Kinman & Wray, 2013; Teichler et al. 2013). This raises the question of what factors may be playing a buffering role in this relationship so that scholars can keep a positive attitude towards their job even under the presence of increasing psychosocial risks. Endeavors to address these mechanisms have characterized much of the organizational psychology literature for over two decades, reflecting, in particular, the scholarly and managerial concerns and awareness that drive the financial and moral need to reduce strain in the workplace (Judge, Weiss, Kammeyer-Mueller, & Hulin, 2017). In this regard, it is worth noting that until recently organizations psychology research had traditionally mainly focused on the study of negative psychological states such as anxiety or exhaustion (Bakker & Demerouti, 2014; Bakker, Schaufeli, Leiter, & Taris, 2008), neglecting, to a considerable extent, the study of the psychological and organizational mechanisms that lead to positive states (Kammeyer-Mueller, Judge, & Scott, 2009; Salanova, Martínez, & Llorens, 2014; Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2014). In spite of this, some studies have shed some light on the factors affecting the relationships between work stressors and outcomes related to individuals’ well-being. For instance, Van Yperen and Snijders (2000) provide evidence about the moderating role of general self-efficacy in the relationship between job demands and psychological health symptoms. In a similar vein, Makikangas & Kinnunen (2003) show that under demanding work conditions such as high time pressure, high job insecurity, and poor organizational climate employees who are more optimistic tend to report lower levels of mental distress than their less optimistic counterparts. More recently, Pierce and Gardner (2004) report that organization-based self-esteem buffers the effects of demanding working conditions such as role ambiguity on individuals’ physical strain and job dissatisfaction.

Another promising construct in the study of stressor-strain relationships is work engagement (Britt & Bliese, 2003; Britt, Castro, & Adler, 2005), that is to say, a positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind that is characterized by high levels of vigor, dedication, and absorption (Bakker, Albrecht, & Leiter, 2011; Bakker & Demerouti, 2014). However, as argued by Macey and Schneider (2008), the potential consequences and effects of work engagement are still poorly explored in the literature, especially in relation to its buffering power against psychosocial risks (Britt & Bliese, 2003). In regards to the Argentinian context in particular, though some studies have successfully described the nature of work in higher educational settings (e.g., García de Fanelli & Moguillansky, 2014; Groisman & García de Fanelli, 2009), evidence of its effects on scholars’ job satisfaction and of the role that work engagement plays in these dynamics is still overwhelmingly limited.

Thus, drawing on the principles of the demand-resource theory (Bakker & Demerouti, 2014) and the ISTAS model (Moncada & Llorens, 2004), this paper explores the buffering role of work engagement in the relationship between perceived exposure to psychosocial risks and affective job satisfaction of a sample of scholars of a public university in Argentina with the purpose of advancing our understanding of the psychosocial risks involved in academics’ work life and of their effects on academics’ job attitudes. To achieve this, the paper begins by briefly describing the nature of scholars’ work in Argentinian public universities and providing an analysis of the prevalence of a set of psychosocial risk factors that are often found to be associated with decreasing levels of job satisfaction. This is followed by the results regarding the moderating role of engagement in the relationship between psychosocial risks and job satisfaction. Finally, the paper discusses the possible mechanisms that may explain the findings, raising questions of practical implications and identifying future lines of research.

Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

Psychosocial Risks and Job Satisfaction in Academics

The current job demands involved in leading a successful academic life have turned this career path into a highly stressful one (Fredman & Doughney, 2012; Hakanen et al., 2006; Kinman & Wray, 2013). On the one hand, academics face considerable cognitive demands (Salanova et al., 2005) as a result of the increasing workload involving high levels of concentration, precision, and attention to detail when delivering lectures, grading, participating in research projects and supervising student theses, among others (Klassen & Chiu, 2010; Liu & Ramsey, 2008). In their efforts to meet these cognitive demands, on the other hand, scholars also face competing emotional demands as they are required to maintain emotional connections with various social actors, including students, academic authorities, representatives of the labor market, and the community, both local and global, lay and academic (Salanova et al., 2005; Yin, Lee, & Zhang, 2013). Indeed, leading an academic life involves undergoing highly emotional processes as scholars must be able to successfully manage and regulate their emotions to achieve teaching effectiveness and top research outcomes, in addition to creating a positive learning environment (Gates, 2000; Winograd, 2005), while they also undertake the task of positioning their institutions internationally as they participate in academic activities around the world. Such cognitive and emotional demands also tend to increase the likelihood of work-family conflicts as academics struggle to cope with these often competing demands and resulting strain imposed by both roles (Greenhaus & Allen, 2011; Ilies et al., 2007).

Ideally, these job demands need to be met with appropriate job resources, that is to say, those physical, psychological, social, and organizational factors that are functional to reaching goals and stimulating both personal and professional growth (Bakker & Demerouti, 2014). Undoubtedly, when job resources are scarce, this situation increases the psychosocial risks imposed on scholars which, if not successfully managed, may lead to strain and job dissatisfaction (Schaufeli & Salanova, 2002; Spector, Chen, & O’ Connell, 2000). For instance, since autonomy is a basic universal psychological need that nourishes individuals’ intrinsic motivation (Gagne & Deci, 2005), insufficient levels of work control tend to lead to lower levels of job satisfaction as scholars feel less able to face their job demands and experience less self-motivation (Salanova et al., 2005; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2014). Similar outcomes are expected when levels of social support from colleagues and leaders, which reflect the extent to which a job offers opportunities for advice and assistance from others (Morgeson & Humphrey, 2006; Morgeson & Humphrey, 2008), are deficient, as they are not only relevant for enhancing effective job performance but also essential for fulfilling social needs (Collins, 2007; Heaney & Israel, 2008). This is also true for those cases in which individuals believe that rewards such as pay, recognition, or career opportunities are unfairly distributed in the organization (Cohen-Charash & Spector, 2001; Gillespie, Walsh, Winefield, Dua & Stough, 2001). These factors, naturally, have been found to play a vital role in scholars’ job satisfaction levels and well-being (Kinman & Wray, 2013; Kinman, Wray, & Strange, 2011). Moreover, previous studies have also shown that job insecurity, that is to say, an individual’s prolonged worry or concern about the continuity of their current job situation, may result in strain (Mauno, Kinnunen & Ruokolainen, 2007; Mauno, Leskinen, & Kinnunen, 2001) and job dissatisfaction (Reisel, Probst, Chia, Maloles, & König, 2010; Sverke, Hellgren, & Näswall, 2002; Waltman, Bergom, Hollenshead, Miller, & August, 2012), as working is highly instrumental for fulfilling both basic and superior needs (Weir, 2013).

The psychosocial risk factors described above have been found to play a salient role in educational settings in the Ibero-American context. Botero-Álvarez (2012), for instance, identifies increasing work overload, time pressure, insufficient acknowledgement and support, and inadequate physical working conditions and payment as being the most salient psychosocial risks faced by Latin-American academics. In a more recent study conducted with 500 scholars of Mexican public universities, Unda et al. (2016) found that the perils involved in student-lecturer relationships and the limited access to relevant physical resources due to budget restrictions are the main psychosocial risk factors affecting scholars in this context. In another study on 621 Spanish university academics, García, Iglesias, Saleta, and Romay (2016) identified a high prevalence of psychological demands, low esteem, high levels of double presence, low social support, and high job insecurity as overriding psychosocial risks. In the case of Argentinian scholars, though some studies focusing on the Argentinian context have been successful in describing the nature of work in higher educational settings (e.g., García de Fanelli & Moguillansky, 2014; Groisman & García de Fanelli, 2009), it was not possible to find literature that provides evidence of the effects of psychosocial risk factors on scholars’ attitudes, behavior, well-being and, in particular, job satisfaction in this context. However, based on the abundant evidence provided on this matter in the international literature, as discussed above, we hypothesize that:

H1: Perceptions of higher exposure to psychosocial risks (i.e., psychological demands, insufficient autonomy, lack of social support and leadership, double presence, insufficient esteem, and insecurity about the future) will be related to lower levels of job satisfaction.

Moderating Role of Work Engagement

In spite of the stress involved in leading a successful academic life, previous studies have recognized that the majority of scholars tend to experience positive emotional states (Bentley et al. 2013; Hakanen et al., 2006; Kinman & Wray, 2013; Teichler et al. 2013). This evidence suggests that the effects of psychosocial risks on scholars’ well-being may be influenced by other factors that may buffer its detrimental consequences. In this sense, personal resources such as optimism, organizational-based self-esteem, self-efficacy, and self-esteem have received considerable attention in the study of the relationships between stressors and strain in organizational psychology research (Makikangas & Kinnunen, 2003; Pierce & Gardner, 2004; Van Yperen & Snijders, 2000; Xanthopoulou, Bakker, Demerouti, & Schaufeli, 2007).

Besides the aforementioned personal factors, another promising construct in the study of the mechanisms through which scholars experience job satisfaction under the presence of psychosocial risks is work engagement, which is usually measured with the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES; Schaufeli, Bakker, & Salanova, 2006). In this scale, work engagement is conceptualized as a positive, fulfilling state at work that is defined by vigor, dedication, and absorption (Bakker & Demerouti, 2014). Vigor means high levels of energy, mental resilience, and persistence while working despite the difficulties. Dedication, the second core dimension of engagement, is characterized by a sense of significance, enthusiasm, challenge, and inspiration. Finally, absorption is characterized by intense concentration and engrossment with one’s work, whereby time passes quickly and the person experiences difficulties with disconnecting themselves from work.

In spite of the fact that the moderating role of work engagement in stressor-strain relationships has certainly been understudied in the field of organizational psychology (Britt & Bliese, 2003), this modest body of literature has much to offer to the investigation of scholars’ job satisfaction as a response to psychosocial risk factors. To provide an example, in a study conducted by Leiter & Harvie (1998) with a sample of 3,312 employees from a large healthcare institution, the authors found that work engagement indeed moderated the relationship between supportive supervision, confidence in management, effective communication, work meaningfulness, and acceptance of change. In a more recent study, Britt & Bliese (2003) analyzed whether engagement moderated the stressor-strain relationship in a sample of U.S. soldiers. In their research, Britt & Bliese (2003) found evidence of the buffering role of engagement against stress. Specifically, they reported that when stressor levels were high, soldiers who were engaged with their job reported less elevation in reports of psychological distress than soldiers who were less engaged with their job. Similar results are later reported by Britt et al. (2005) in their longitudinal study conducted on a sample of 177 U.S. soldiers, revealing that highly engaged soldiers were less likely to experience negative health consequences under high levels of training and work hours in comparison to less engaged soldiers.

In light of this evidence, we hypothesize that work engagement might act as a shield that protects scholars from stressful organizational environments. Following Britt and Bliese’s (2003) argument, we believe that work engagement might have a protective role in academics who are exposed to higher psychosocial risks. Drawing on Kahn’s (1990) hypothesis that employees who are highly engaged with their job tend to fully invest their cognitive, motivational, and emotional energy on their tasks at hand, we believe that highly engaged scholars are more likely to focus on any other aspects of any given task than “on stressful circumstances that are occurring outside the sphere of the individual’s immediate job performance” (Britt & Bliese, 2003, 248) and, as a consequence, the effects of psychosocial risks on scholars’ job satisfaction will be less detrimental if they feel highly engaged with their jobs. Therefore, we hypothesize that:

H2: Work engagement will moderate the relationship between perceived exposure to psychosocial risks and job satisfaction.

Method

Context of the Study

This present study was conducted in a faculty of an Argentinian public university, in the province of Buenos Aires. According to an internal database (20151), the faculty is composed by 414 scholars and 3,905 students. The faculty is organized into a set of departments, namely, Management, Economics, and Accounting, each of which are, subsequently, divided into different courses. Regarding their hierarchy, scholars can be classified into three main groups: professors (about 31 percent of the academic staff at the faculty), senior tutors (about 12 percent of the academic staff at the faculty), and graduate assistants or tutors (about 57 percent of the academic staff of the faculty). Professors are usually in charge of planning, coordinating, and monitoring courses as well as delivering lectures to groups of about sixty to one hundred and fifty students. Senior tutors are the link between professors and graduate assistants or tutors, and are in charge of coordinating and monitoring tutorials. Graduate assistants or tutors are in charge of teaching tutorials and supervising the learning process of groups of between forty to eighty students. In addition to their hierarchy, every position (including professorships) may involve either a full-time (40 hours a week) or a part-time contract (10 hours a week), and only full-time scholars (less than 10 percent of the academic staff of the faculty) have a contract to do both teaching (12 hours a week) and research (28 hours a week), while they are also encouraged to participate in technology transfer projects on the side.

Participants

A total of 177 scholars, representing a 42.75% overall response rate, participated in this study by completing an online survey. The age of the respondents ranged from 23 to 70, with a mean (standard deviation in parenthesis) of 44.40 (11.76) years old. About 70% of the participants were female, 36.36% were professors, 12.43% were senior tutors, and 24.88% had full-time positions. The tenure of the respondents ranged from 1 to 45 years, with a mean of 17.49 (10.51) years. Tenure in the current position ranged from 1 to 30 years, with a mean of 8.66 (8.41) years. Comparisons made between the sets of values and the population information outlined above allowed the researchers to conclude that the sample shows appropriate conditions of representativeness.

Procedure

We first contacted the faculty’s maximum academic authority, the Dean, and asked for authorization to conduct the study. After agreeing on the research design, survey administration procedures, and time requirements, the Dean provided clearance for sending online invitations and a link to an online survey to 414 academics. Confidentiality was guaranteed since participation was anonymous and no personal information (e.g., e-mail address) was required to enter the online survey. Participants were asked to complete a consent form before starting the survey.

Measures

Overall job satisfaction. The overall job satisfaction was measured with a Spanish version of the Brief Index of Affective Job Satisfaction (BIAJS; Thompson & Phua, 2012) validated in Pujol-Cols & Dabos (2017). This scale has been specifically designed for assessing the affective components of job satisfaction, through a brief scale composed of four items (including “I find real enjoyment in my job”), with a response scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The BIAJS was translated into Spanish by the authors with the assistance of an expert in linguistics and translation. Both the authors and the translator independently translated the scales from English into Spanish, and then cross-checked the translation, resolving differences through mutual agreement. Each other’s translated version had the purpose of ensuring that each item captured cross-cultural content validity and contextual equivalence to the original scales. An overall alpha of .83 suggested high internal consistency, which is consistent with previous results reported for the English version (Thompson & Phua, 2012). The items were averaged to form a single overall job satisfaction score.

Perceived exposure to psychosocial risks. The perceived exposure to psychosocial risks at work was measured with the short version of the Questionnaire for the Assessment of Work-related Psychosocial Risks Copsoq-Istas 21 (Cuestionario de Evaluación de Riesgos Psicosociales en el Trabajo Copsoq-Istas 21; Moncada & Llorens, 2004), a Spanish version of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (Kristensen, Hannerz, Høgh, & Borg, 2005). This instrument was developed by scholars from the Instituto Sindical de Trabajo, Ambiente y Salud de España [Spanish Trade Union Institute of Work, Environment, and Health] based on the seminal contributions made by Karasek (1979) in his demand-control model and Siegrist (1996) in his effort-reward imbalance model. It is composed of 38 items and has been specifically designed for identifying, measuring, and evaluating the exposure of employees to six categories of work factors related to individuals’ psychosocial health:

• Psychological demands (α in this study = .62), which refers to the volume and intensity of workload as well as to the transfer of feelings towards the job (6 items, including “My workload is irregular which causes work cumulate” and “My job is emotionally exhausting”).

• Insufficient autonomy (α in this study = .81), which refers to the extent to which the employee feels that they are not capable of exerting some influence in the way tasks are performed and that the job does not offer them enough chances for developing and applying different knowledge and abilities (10 items, including “My opinion is taken into account when tasks are assigned to me”, reverse scored).

• Job insecurity (α in this study = .73), related to the degree to which an employee is worried about possible changes in their work conditions (4 items, including “I am worried about the possibility of getting fired”).

• Lack of social support and leadership (α in this study = .85), which refers to the degree to which an employee does not feel emotionally supported by either their co-workers or supervisors during task specification and performance (9 items, including “I am given all the information I need for doing my job properly”, reverse scored).

• Double presence (α in this study = .61), which refers to the degree to which an employee feels that they need to face both work and home-related demands simultaneously (4 items, including “There are times when I feel I have to be at work and at home at the same time”).

• Insufficient esteem (α in this study = 85), which refers to the extent to which an employee feels that the rewards and recognition they receive are unfair in regards to the contribution they make (4 items, including “My superiors acknowledge my work in the way I deserve”, reverse scored).

Responses for all six scales of the Copsoq-Istas 21 were anchored on a 5-point scale with responses ranging from 0 to 4 (except for reverse scored questions). The total score for each of the six core dimensions was averaged individually. The corrected overall reliability for the total scale was estimated in .75, suggesting acceptable internal consistency, which is consistent with its validation in other organizational settings and countries, such as England, Belgium, Netherlands, Germany, Brazil, and Switzerland (Moncada & Llorens, 2004), showing favorable psychometric properties.

Work engagement. Work engagement was measured with the Spanish nine-item version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES-9; Schaufeli et al., 2006). The items in the UWES-9 reflect three underlying dimensions, which are measured with three items each: vigor (e.g., “at my work, I feel bursting with energy”), dedication (e.g., “My job inspires me”), and absorption (e.g., “I get carried away when I am working”). All items of work engagement subscales were anchored on a seven-point scale, ranging from 0 (never) to 6 (always). Consistent with previous research using the English version of the survey (e.g., Schaufeli et al., 2006), in this study the Spanish UWES-9 reported alpha coefficients of .86 for vigor, .83 for absorption, and .84 for dedication, which suggests high internal consistency.

Control variables. Based on previous findings reported by Unda et al. (2016) and García et al. (2016) in higher education settings, we identified four variables that were expected to covary with our independent and dependent variables. These variables were: age, gender, hierarchy of current position, and hours worked per week.

Data Analysis

First, we examined whether work engagement and job satisfaction are indeed distinct constructs by comparing two competing models using structural equation modeling in AMOS 22. Second, we tested a one-factor structure of the work engagement construct through a first-order confirmatory factor analysis. Third, we conducted hierarchical regression analyses with work engagement, perceived exposure to psychosocial risks, interactions between work engagement and perceived exposure to psychosocial risks, and job satisfaction as variables using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 24). Fourth, we plotted the slopes of all significant interactions at one standard deviation below and above the mean (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2003; Frazier, Tix, & Barron, 2004). Fifth, we followed the procedure used by Kacmar, Collins, Harris, and Judge (2009) and conducted simple slope tests by using the software designed by Preacher, Curran, and Bauer (2006).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics and correlations among the variables of interest are presented in Table 1. In regards to the study of psychosocial risk factors in this group of Argentinian scholars, results show that, on the one hand, academics in our sample seem to be exposed to moderate-high levels of psychological demands (M = 1.92, SD = 0.54) and double presence (M = 2.13, SD = 0.73) and to a lesser extent to insufficient esteem (M = 1.57, SD = 0.91). On the other hand, results showed a low prevalence of insufficient autonomy (M = 0.98, SD = 0.57), lack of social support and leadership (M = 1.14, SD = 0.64), and job insecurity (M = 1.35, SD = 0.89).

Table 1 Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations among Variables

Note. N = 177; correlations greater than .12 are significant at p < .10; correlations greater than .15 are significant at p < .05; correlations greater than .19 are significant at p < .01; scale reliabilities (alpha coefficients) are on the main diagonal in bold; control variables are not included in this table for simplicity.

The six psychosocial factors showed low to moderate correlations among each other (ranging from .12 to .73). Only insufficient autonomy, lack of social support and leadership, insufficient esteem, and job insecurity displayed negative and statistically significant correlations with job satisfaction, suggesting that stronger perceptions of exposure to these four psychosocial risks are associated with lower levels of job satisfaction. In terms of the core traits of work engagement, as expected, measures of vigor, absorption, and dedication displayed high and positive non-zero correlations with one another (r above .76, p < .01). Moreover, work engagement was found to be positively related to overall job satisfaction (r = .76, p < .01), suggesting that more engaged employees are likely to feel more satisfied with their jobs.

The high correlations found between work engagement and job satisfaction are consistent with what has been previously reported by Alarcon and Lyons (2011). To test whether work engagement and job satisfaction are indeed distinct constructs, we followed Alarcon and Lyons’ (2011) procedure and compared two competing models using structural equation modeling in AMOS 22. Following recommendations made by Bollen and Long (1992), we examined and compared various indices of overall fit, including chi-square (χ2), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CIF), goodness of fit index (GFI), normed fit index (NFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and parsimony goodness-of-fit index (PGFI). CFI, GFI, NFI, and TLI values that exceed .90, RMSEA values as high as .08, and PGFI of around .50 indicate a good fit (Byrne, 2001).

In the first model, we entered work engagement and job satisfaction as two latent variables covarying with each other. In the second model, all the observed variables were hypothesized to load onto the latent construct of work engagement. Also consistent with Alarcon and Lyons (2011), the model of work engagement and job satisfaction as two distinct but related factors provided good fit to our data: χ2(64, N = 177) = 123.64, p < .001, CFI = .96, RMSEA = .07, NFI = .93, TLI = .95. The model with job satisfaction included under the work engagement factor provided an acceptable but relatively poorer fit: χ2(65, N = 177) = 166.43, p < .001, CFI = .94, RMSEA = .09, NFI = .90, TLI = .91. We used chi-square differences to compare models 1 and 2. Results revealed that the chi-square difference test was significant, χ2(1, N = 177) = 42.79, p < .001, suggesting that the model with work engagement and job satisfaction as separate factors provide a better fit to the data, which is consistent with the findings in Alarcon and Lyons (2011), Mudrak et al. (2017), Rich et al. (2010), and Kašpárková, Vaculík, Procházka, and Schaufeli (2018).

Moderation Hypothesis

The factor structure of the engagement construct is still a matter of debate (Alarcon & Lyons, 2011). Indeed, though a three-factor structure seems to have been widely accepted in the literature (Schaufeli, Salanova, González-Romá, & Bakker, 2002), some scholars also support the idea of a one-factor solution. For instance, Seppälä et al. (2009) recommend using a unidimensional solution of work engagement when addressing its relationship with other variables as a way to reduce multicollinearity. To test the one-factor structure of the work engagement construct, then, we conducted a first-order factor analysis in AMOS 22. The one-factor model provided an acceptable fit to the data, χ2(25, N = 177) = 50.64 (p < .01), CFI = .98, GFI = .93, RMSEA = .08, NFI = .96, TLI = .97, PGFI = .52. As a result, we calculated the work engagement composite as the mean value of the scores obtained for each of the nine items.

To test H1 and H2 we conducted hierarchical regression analyses (Raudenbush, Bryk, Cheong, Congdon, & du Toit, 2004) to examine the effects of work engagement and work-related psychosocial risk factors in predicting job satisfaction. As a preliminary step, both the independent variables (i.e., psychological demands, insufficient autonomy, lack of social support and leadership, double presence, insufficient esteem, and job insecurity) and the moderator (i.e., work engagement) were mean-centered (see Cohen et al., 2003) and interaction terms were created between each independent variable and the moderator. Following Aiken and West (1991), we conducted a hierarchical regression analyses in three steps as follows: the control variables were entered in the first block, the independent variable (e.g., psychological demands) and the moderator (i.e., work engagement) were entered in the second block, and the interaction term (e.g., psychological demands x engagement) was entered in the third block, as shown in Tables 2 through 7. Finally, we plotted all significant interactions at “high” and “low” values of the predictor and moderator (i.e., one standard deviation above and below the mean) and assessed their slope.

Table 2 Hierarchical Regression Results for Psychological Demands

Note. N = 177.*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

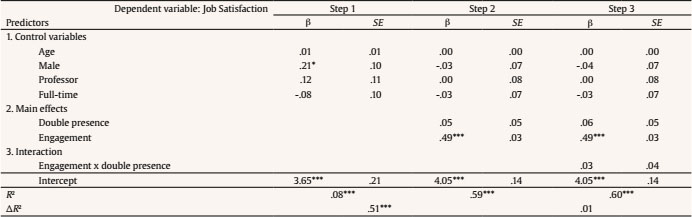

Table 3 Hierarchical Regression Results for Double Presence

Note. N = 177.*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

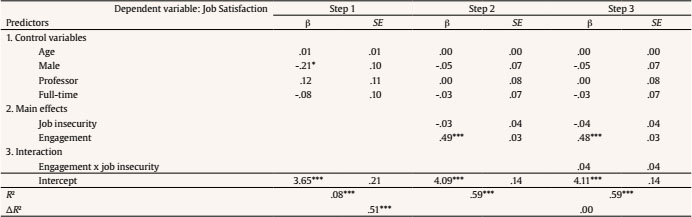

Table 4 Hierarchical Regression Results for Job Insecurity

Note. N = 177.*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

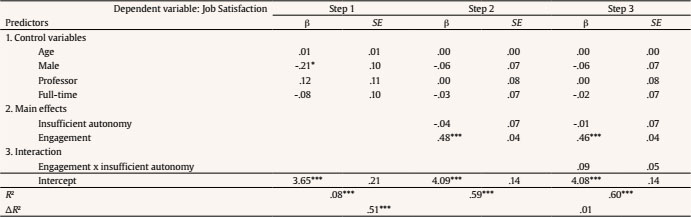

Table 5 Hierarchical Regression Results for Insufficient Autonomy

Note. N = 177.*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Table 6 Hierarchical Regression Results for Lack of Social Support and Leadership

Note. N = 177.*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

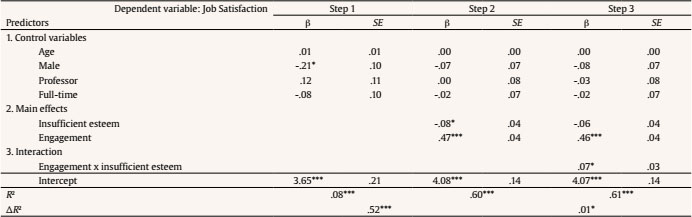

Table 7 Hierarchical Regression Results for Insufficient Esteem

Note. N = 177.*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

High job demands. As shown in the top portion of Table 2, none of the control variables were significant predictors of job satisfaction. Moreover, the three psychosocial risk factors representing job demands failed to significantly explain job satisfaction, therefore not supporting H1. Work engagement, on the other hand, was found to be a significant predictor in the three cases (β =.49, p < .01). H2 proposed that the negative relationship between perceived exposure to psychosocial risks and job satisfaction was higher for those individuals who reported lower levels of work engagement. As shown in the bottom portion of Table 2, we found that work engagement indeed moderated the psychological demands-job satisfaction relationship (β = .11, p < .05). No moderating effects, however, were found for the double presence-job satisfaction and job insecurity-job satisfaction links (Tables 3 and 4).

To evaluate whether the significant interaction provided support to H2, we plotted the slopes at one standard deviation below and above the mean (Cohen et al., 2003; Frazier et al., 2004; see Figure 1). To further test the interaction, we followed the procedure used by Kacmar et al. (2009) and conducted simple slope tests by using the software designed by Preacher et al. (2006). Our results show that the slope for the high engagement line is significant, t(169) = 2.07, p < .05, unlike the slope for the low engagement line, t(169) = -0.62, p = .53. This suggests that an increase in psychological demands seems to have a positive effect on job satisfaction when individuals are highly engaged, thus partially supporting H2.

Figure 1 Graph of the Interactive Effect of Work Engagement on the Relationship between Psychological Demands and Affective Job Satisfaction.

Low job resources. We obtained similar results for the three remaining psychosocial risk factors that represent low job resources. As it can be seen in the middle portion of Tables 5, 6, and 7, our results indicate none of these psychosocial risk factors significantly explained job satisfaction, whereas work engagement was found to be a significant predictor in the three cases. As shown in the bottom portion of Tables 5, 6, and 7, only the interaction terms between lack of social support and leadership and work engagement and between insufficient esteem and work engagement were statistically significant.

We also used simple slope tests to assess the interactions involving low job resources. Regarding the lack of social support and leadership (see Figure 2), our results indicate that only the low engagement bond is significant, t(169)= -2.40, p < .05. Similar results were obtained for insufficient esteem (see Figure 3), where only the low engagement line was found to be significant, t(169) = -2.96, p < .01. These results suggest that the negative effects of both psychosocial risk factors are greater in individuals who report lower levels of work engagement, which partially supports H2.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the moderating role of work engagement in the relationship between perceived exposure to psychosocial risks and job satisfaction in a sample of Argentinian scholars. To this end, we considered six psychosocial risk factors as highly relevant for explaining employees’ job satisfaction (namely, psychological demands, insufficient autonomy, lack of social support and leadership, double presence, insufficient esteem, and job insecurity) and stated that the impact of these psychosocial risk factors at work on job satisfaction would be moderated by work engagement. Regarding their main effects on job satisfaction, hierarchical regression analyses revealed that none of the psychosocial risk factors showed incremental explanatory power over job satisfaction once work engagement was considered. Work engagement, on the other hand, was found to be a strong and significant predictor of scholars’ job satisfaction, which is consistent with what has been previously reported in the literature (e.g., Alarcon & Lyons, 2011; Kašpárková et al., 2018; Mudrak et al., 2017; Rich et al., 2010; Saks, 2006).

Regarding the buffering hypothesis, hierarchical regression analyses resulted in three significant two-way interactions, which means that work engagement was indeed found to moderate the impact of psychological demands, lack of social support and leadership, and insufficient esteem on scholars’ job satisfaction. These three interactive effects explained incremental variance in job satisfaction, as the variation in the R2 coefficient was statically significant. Thus, our results revealed that the detrimental effects of psychosocial risks on job satisfaction were higher for those scholars who reported lower levels of work engagement. In light of this evidence, we believe that work engagement may act as a shield that protects scholars from highly demanding and/or poorly resourceful working conditions, which is also consistent with previous results reported by Britt and Bliese (2003) and Britt et al. (2005) on the role of engagement in the stressor-strain relationship in other organizational settings. There are several reasons why work engagement may help mitigate the effects of perceived exposure to psychosocial risks on job satisfaction. First, highly engaged individuals tend to fully invest their cognitive, motivational, and emotional energy on their work and the task at hand (Kahn, 1990; May, Gilson, & Harter, 2004), and to be able to concentrate more and be more absorbed in their work (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007; Nakamura & Csikszentmihalyi, 2014), often to the point of disregarding any other negative extrinsic aspects of their job such as lack of support from their leaders/colleagues and of resources (Britt & Bliese, 2003; Britt et al., 2005). These individuals also tend to experience a sense of enthusiasm and enjoyment when engaging in their work roles, which are basic dimensions of intrinsic motivation (see Salanova & Schaufeli, 2008) and do, thus, often report higher levels of job satisfaction (Alarcon & Lyons, 2011). Second, employees who are more engaged also tend to be more optimistic (Bakker et al., 2008; Makikangas & Kinnunen, 2003) and to strongly believe that ‘things will get better’, that more resources will eventually be provided, and that the psychosocial risks they may encounter are a challenge to be faced rather than an obstacle to job performance. Last but not least, highly engaged employees tend to be more self-efficacious and are therefore more confident of their capabilities to manage psychosocial risks (Bakker et al., 2008; Cheung, Tang, & Tang, 2011).

In addition, our results also revealed that increasing psychosocial demands may have a positive effect on job satisfaction when scholars are highly engaged. Thus, by possibly viewing these psychosocial risks as challenges rather than as obstacles and by possessing the aforementioned positive personal resources (e.g., optimism, self-efficacy, resiliency), those highly engaged scholars who participated in this study seem to be more likely able to cope with the growing demands of the fast-changing world of academia. Naturally, from an organizational perspective, this raises vital questions related to the ethical implications involved in relying on scholars’ positive personal resources for getting the job done at the expense of turning a blind eye on the strains caused by the work demands imposed on scholars.

In this regard, although this study provides valuable insights on the protective role of work engagement in the face of psychosocial risks, we cannot help wondering when these psychosocial risks actually would cause strain on highly engaged scholars so that they would have detrimental effects on their job satisfaction. In other words, where do we draw the boundary between ‘healthy’ stress and ‘counterproductive’ stress for these engaged scholars? When do these psychosocial risks become too heavy a burden for them that they turn into obstacles that can cause anxiety and burnout? When do the job demands imposed on today’s scholars become such a burden that even the highly engaged scholars succumb to their overwhelming effects? When is the balance lost and what impact does this have on their attitudes, behavior, and well-being?

Since research in this field has consistently shown that job resources such as social support, autonomy, and learning opportunities are positively related to work engagement (Bakker & Demerouti, 2008), we cannot emphasize the importance of improving scholars’ working conditions enough, because, as this study shows, engagement seems to help scholars cope with the psychosocial risks they face as part of today’s academic life. Job resources then play an intrinsic motivational role as they boost employees’ growth, learning, and development, thus helping fulfill basic human needs. At the same time, they also play an extrinsic motivational role as they are instrumental in achieving work goals, consequently fostering individuals’ willingness to dedicate incremental efforts, which increases the likelihood of performing tasks successfully (see Bakker et al., 2008.

Contributions to Scholarship

This study extends the demand-resource theory and the ISTAS model by shedding light on the role of work engagement in the relationship between work-related psychosocial risk factors and job satisfaction in a group of Argentinian scholars. Our results reveal that work engagement plays a significant role in moderating the effects of psychological demands, lack of social support and leadership, and insufficient esteem on the job satisfaction of these scholars. Our paper then provides evidence that work engagement may act as a shield that protects scholars from highly demanding or poorly resourceful working conditions. These findings make a substantial contribution to the fields of organizational psychology and management research by providing new insights into the stressor-strain relationship and, particularly, into the processes through which individuals maintain a positive attitude in the presence of work stressors.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

In addition to the theoretical and empirical contributions our study makes in this largely underexplored field of research, and in particular, in the context of Argentinian universities, some reflections need to be made in order to provide new avenues for future research. First, since perceived exposure to psychosocial risks, affective job satisfaction, and work engagement were measured at the same time, some may argue that our results may be affected by the common-method bias (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, 2003). Following the procedure used by Li, Mobley, and Kelly (2013), this issue was addressed by conducting Harman’s one-factor test in which all the observed variables in our study were simultaneously entered into an exploratory factor analysis. Results revealed that the one single factor accounted only for 26.01% of the variance, suggesting that the common-method bias did not affect our data or our results (see Podsakoff et al., 2003). In this light, we suggest that future studies should further develop this matter by either employing longitudinal designs or measuring the three constructs at different points in time (see Judge, Bono, Erez, & Locke, 2005 for a procedure for reducing common-method variance).

Second, some researchers may argue that the size and characteristics of our sample could have affected the robustness of our estimations. However, in spite of the difficulties involved in tracing significant interaction effects (see Frese, 1999), three out of six two-way interactions were identified in our study. Future research should examine the relationships proposed in our models by using larger and more heterogeneous samples of employees, who are exposed to a wider range of the variables of interest.

Third, though work engagement and job satisfaction were found to be two distinct constructs in our sample, which is consistent with what has been reported in prior research (Mudrak et al., 2017; Rich et al., 2010), some overlap between these two was observed. In this regard, we agree with Alarcon and Lyons’ (2011) recommendation that the engagement-job satisfaction relationship should be explored by using longer scales of both constructs, such as the UWES-17 in the case of engagement and the Job Descriptive Index (Smith, Kendall, & Hulin, 1969) in the case of job satisfaction. This may be an effective strategy for increasing variance and, therefore, for providing a comprehensive assessment of the relationship between both constructs.

Finally, although a three-factor model of engagement has received more support in the literature than the one-factor model (Schaufeli et al., 2002), a one-factor solution displayed a good fit to our data, which provides support to the findings in Alarcon and Lyons (2011). Future research could explore how the three dimensions of engagement interact with specific psychosocial risk factors and, in particular, the mechanisms that may explain such patterns. In this regard, though some studies have been conducted so far on the role of optimism, organizational-based self-esteem, and self-efficacy in the context of the demand-resource model (e.g., Xanthopoulou et al., 2007), other personal resource constructs such as the core self-evaluations (Judge et al., 2005) could also be useful in explaining these dynamics.