Introduction

Studying the relationship between followers and leaders is obviously important for understanding leadership. However, as Uhl-Bien, Riggio, Lowe, and Carsten (2014) pointed out, until recently little attention has been paid in leadership research to the psychology of followers. In this paper we focus on followers’ needs for guidance, security, and comfort and propose a new way to look at the follower-leader relationship through the lens of attachment theory – one of the most important theories in the study of interpersonal relationships (Bowlby, 1982; Shaver & Mikulincer, 2007).

The attachment theory was formulated by Bowlby (1982) to describe and explain the emotional bonds established between children and their caregivers in the first years of life. During infancy and childhood, parents or other caregivers occupy the role of protective others (attachment figures) who provide support, comfort, and security. However, during adulthood there are additional relationship partners who can serve as attachment figures. We, following Mayseless (2010) or Mikulincer and Shaver (2016), hypothesize that leaders may be among those figures, because they can be an important source of security for their followers, especially in demanding and challenging contexts.

In order to analyze leadership from an attachment perspective, we need first to determine whether followers tend to perceive leaders as attachment figures. For this reason, the main purpose of the present research is to develop a reliable and valid self-report scale assessing the extent to which subordinates perceive their leaders as security-providing attachment figures in organizational settings. A second and related goal is to begin examining the consequences of this perception for important organizational outcomes (e.g., work engagement, burnout).

The idea that follower-leader relationships are similar in many respects to the attachment relationships between children and parents was already present in Freud’s psychoanalytic writings (Freud, 1939). Both the role of leader and the role of parent involve protecting and taking care of others who are less powerful (children or followers, respectively) and whose fate depends to a certain extent on them as attachment figures (Mayseless & Popper, 2007). As Bowlby (1988) pointed out, the tendency to establish special bonds with certain figures (through the activation of what he called the attachment behavioral system) is due to inborn needs that, although most evident and important early in life, continue to be active over the entire lifespan.

According to the attachment theory (Ainsworth, 1991; Hazan & Shaver, 1994; Trinke & Bartholomew, 1997), a relationship partner has to fulfill five functions to be perceived as a security-providing attachment figure: (a) secure base – people tend to perceive their attachment figures as supporting and encouraging their pursuit of non-attachment goals in a safe environment; (b) safe haven – people tend to perceive their attachment figures as a source of protection, comfort, calm, and reassurance in times of need; (c) responding warmly to proximity seeking, given that people tend to seek and benefit from proximity to an attachment figure in times of need; (d) emotional ties – people tend to feel positive emotions toward and in the context of their attachment figures; (e) separation distress – people tend to feel distressed when kept separated from their attachment figure. A leader may fulfill all of these functions. For example, Popper and Mayseless (2003) suggested that a good leader is sensitive to followers’ needs, helps them to develop autonomy and initiative, reinforces their successes, and augments their feelings of self-worth. Moreover, followers tend to seek a leader’s proximity, guidance, and support when confronting problems and obstacles within organizational settings, develop positive sentiments toward a supportive leader, and feel comforted and protected by him or her in times of need.

A few studies have initiated the examination of leadership and the follower-leader relationship from an attachment perspective (for reviews, see Mayseless, 2010, Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016; Popper & Amit, 2009). These studies have explored the association between leaders’ attachment orientations in close relationships (frequently assessed with the Experiences in Close Relationships Scale; Brennan, Clark, & Shaver, 1998) and leadership styles and behaviors. Previous studies have also examined the contribution of leaders’ attachment orientations to followers’ well-being and performance (e.g., Davidovitz, Mikulincer, Shaver, Izsak, & Popper; 2007; Ronen & Mikulincer, 2012, 2014). For example, Davidovitz et al. (2007) found that officers’ higher scores on avoidant attachment were associated with soldiers’ reports of more distress and more performance problems during intensive military training. There are also a few studies examining the contribution of compatibility of leaders’ and followers’ attachment orientations (assessed with respect to close interpersonal relationships) to organizational outcomes (e.g., Davidovitz et al., 2007; Keller, 2003).

To date, adult attachment research on leadership has focused exclusively on leaders’ and followers’ attachment orientations in close relationships while examining the contribution of these orientations to leadership style and followers’ well-being and organizational behavior. However, no systematic research has been conducted to establish empirically the extent to which leaders may be perceived as security-providing attachment figures by their followers (beyond and regardless of leaders’ and followers’ attachment orientations) and to examine the consequences of this perception for followers’ organizational behavior. The three studies reported here were designed to examine these basic questions.

Study 1

The goal of Study 1 was to construct a self-report scale tapping the extent to which subordinates perceive their leaders as security-enhancing attachment figures in organizational settings. For this purpose, we designed a scale assessing the five core characteristics of a security-enhancing attachment figure: (a) perceiving the figure as a secure base (e.g., “I think my leader would support my growth and advancement on the job”), (b) perceiving the figure as a safe-haven (e.g., “When something bad happens or I feel upset at work I turn to my leader for support”), (c) being a target for followers’ seeking of proximity and support (e.g., “I don’t let too much time pass without being in close contact with my leader”), (d) strong emotional ties with the figure (e.g., “I feel emotionally connected to my leader, whether our relationship is positive, negative, or a combination of the two”), and (e) distress upon separation from the figure (e.g., “If my leader left, I would miss him/her a lot”). We asked a large sample of employees to rate the extent to which they perceived their direct manager or supervisor in the ways described in the scale. To examine the convergent and discriminant validity of the new scale, we used other leadership-related measures (subordinates’ perceptions of leadership style and leader’s efficacy, subordinates’ satisfaction with the leader).

With regard to perceived leadership style, we assessed subordinates’ perceptions of their manager as a transformational, transactional, or passive-avoidant leader (Bass, 1985). Transformational leaders, through their charisma and inspiration, achieve important changes in followers’ attitudes and behaviors, causing them to accomplish more than they expected (Bass, 1985). Popper and Mayseless (2003) proposed that transformational leaders function as “good parents” because they pay attention to their followers’ needs, establish strong emotional bonds, and promote subordinates’ growth. For these reasons, we expected a positive association between subordinates’ perception of their manager as a security-enhancing attachment figure and the extent to which they perceived him or her as a transformational leader. Transactional leaders may also have positive effects on followers’ performance by rewarding followers’ positive behaviors and punishing negative behaviors (Bass, 1985). Having a clear and coherent representation of the system of organizational rewards and punishments may provide employees with a sense of control and security. For this reason, we expected transactional leaders also to be perceived as security-enhancing attachment figures, but to a lesser degree than transformational leaders, because transactional leaders lack the personalized attention and inspiration of transformational leaders. Finally, passive-avoidant leadership is characteristic of leaders who do not actually lead and are perceived as absent by their employees (Bass, 1985). Their behaviors are quite similar to those of a “bad parent” (Popper & Mayseless, 2003). Therefore we expected an inverse association between this leadership style and perception of the leader as a security-enhancing attachment figure.

Perceiving a leader as a security-enhancing attachment figure means that the leader is performing his/her leadership roles effectively, providing a safe haven and secure base for subordinates. For this reason, we expected positive associations between subordinates’ perceptions of a manager as a security-enhancing attachment figure and their perceptions of the manager’s professional efficacy and their satisfaction with him or her.

Finally, we explored whether the new scale makes unique contributions to the prediction of subordinates’ perception of their manager’s efficacy and their satisfaction with him or her, beyond the contributions of perceived leadership styles. Such unique contributions would indicate the incremental validity of a measure of the perception of the leader as a security-enhancing figure within organizational contexts.

Method

Procedure and participants. Participants were recruited by undergraduate psychology students at a Spanish university who received practicum credits for recruiting participants. Each student contacted at least three participants and provided general instructions for completing the questionnaire in 2014. Participants were then given access to a website where the questionnaire could be completed online. Participants from all over Spain were asked to evaluate their immediate manager or supervisor and several aspects of their organizational life.

Participants (N = 237, 44.7% males and 55.3% females) were included only if they had been working with their manager/supervisor for at least one year (M = 5.25 years, SD = 4.71). Participants’ ages ranged from 22 to 61 years (M = 38.7, SD = 8.25); 60.3 % of them possessed or were studying for a university degree and about 10% had finished high school; of the rest, 12% had received professional training and 7.2% had finished compulsory secondary education. Up to 31.4% of participants occupied a management position. Most of participants worked in a private company (53.9%) or in the public administration (42.9%); for 61.8% of the participants the size of this working environments was big, for 28.6% was medium, and for 9.7% was small. Leaders tended to be men (69.4%) while women leaders only represented 30.6%.

Instruments. To assess subordinates’ perceptions of a manager as a security-enhancing attachment figure, we constructed the 15-item Leader as a Security Provider Scale (LSPS). The scale contained items adapted from past scales developed by Fraley and Davis (1997) and Trinke & Bartholomew (1997) to tap the extent to which parents and romantic partners are perceived as attachment figures. The scale also contained new items formulated by us to tap the five functions of a security-enhancing attachment figure within organizational contexts (secure base, safe haven, proximity seeking, emotional ties, and separation distress). The scale’s instructions and all of the items were formulated to focus participants on their direct manager or supervisor. Participants were instructed to read each item and to indicate the extent to which they agreed or disagreed that the item is descriptive of their manager/supervisor, using a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). In Appendix, we present the 15 items of the new scale.

Perceived leadership style was assessed with a Spanish version (Molero, Recio, & Cuadrado, 2010) of the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ) - Short Form 5X (Avolio & Bass, 2004). Twenty items of this scale assess transformational leadership (e.g., “Instills pride in me for being associated with him/her,” “Articulates a compelling vision of the future”); eight items assess transactional leadership (e.g., “Discusses in specific terms who is responsible for achieving performance targets,” “Directs my attention toward failures to meet standards”); and eight items assess passive-avoidant leadership (e.g., “Is absent when needed,” “Waits for things to go wrong before taking action”). Participants were instructed to rate how frequently their direct manager/supervisor engaged in each of the 36 described behaviors using a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (frequently, if not always). In our sample, Cronbach alpha coefficients for the three subscales were high (ranging from .82 to .93), allowing us to compute total scores for each subscale by averaging the corresponding items. Higher scores reflect greater applicability of a particular leadership style.

As usual in research using the MLQ (Avolio & Bass, 2004), we used five additional items included in this questionnaire to assess perceived leader efficacy and satisfaction with the leader. The perceived leader efficacy subscale is composed of three items (α = .82; e.g., “My leader is effective in meeting organizational requirements”), and the subordinates’ satisfaction with the leader subscale contains two items (α = .82, r = .70, p < .001; e.g., “I am satisfied with his/her methods of leadership”). We computed two total scores by averaging the items corresponding to each subscale.

Results and Discussion

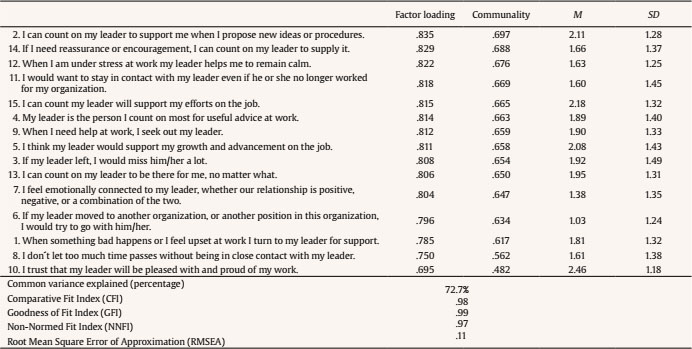

An exploratory factor analysis was performed using the FACTOR software program (Lorenzo-Seva & Ferrando 2006). One single dimension was extracted using the polychoric correlation matrix, parallel analysis (PA) method, robust unweighted least squares (RULS) with the oblique Promin rotation (Table 1). The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test value was .96, over the cut-off value of .80, which indicated that the matrix was well suited to factor analysis. The Bartlett test of sphericity (p < .001) supported the model’s significance. Adjustment indexes indicated an adequate fit (NNFI = .97 and CFI = .98), except for RMSEA = .11 (95% CI .079, .124), which was slightly higher than recommended. The items with higher weights on the single factor belong to the sub-scales of “secure base” and “safe haven.” We use a single total score (the average of the 15 items) in subsequent analyses. The Cronbach alpha for this scale is high (α = .96).

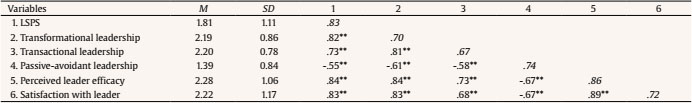

As can be seen in Table 2, Pearson correlations were in line with our predictions. The higher subordinates’ perception of the leader as a security provider, the higher their perception of him or her as a transformational and transactional leader and the lower their perception of him or her as a passive-avoidant leader. Moreover, the higher subordinates’ perception of the leader as a security provider, the higher their perception of the leader’s efficacy and their satisfaction with his or her leadership.

Table 2 Pearson Correlations between Study 1’s Variables

Note. Diagonal elements in italics are the square root of AVE between the constructs and their indicators. For discriminant validity, diagonal elements should be greater than offdiagonals elements in the same row and column. Scores could range from 0 to 4.

**p < .01.

**p < .01, ***p < .001.

In studying the incremental validity of the LSPS, we conducted multiple regression analyses predicting perceived leader efficacy and satisfaction with the leader, while controlling for several sociodemographic variables – gender, age, education level, and time working with leader (Table 3). The predictor variables were the LSPS score and the three leadership style scales. For perceived leader efficacy, the amount of explained variance was R2 = .81 and the betas for LSPS (β = .46), transformational leadership (β = .32), and passive-avoidant leadership (β = -.22) were all significant (p <. 001). Transactional leadership and all the sociodemographic variables made no significant contribution. For satisfaction with the leader, the amount of explained variance was R2 = .80 and the betas for LSPS (β = .46), transformational leadership (β = .44), transactional leadership (β = -.15), and passive-avoidant leadership (β = -.25) were all significant (p < .01). Again, the sociodemographic variables made no significant contribution. These findings indicate that although the LSPS is related to other variables associated with leadership, it makes a unique and significant contribution to explaining subordinates’ perceptions of leader efficacy and subordinates’ satisfaction with their leader. In fact, it is the predictor with the highest beta coefficient in all of the regression equations.

The regression findings are also important for clarifying the association between the LSPS score and the transformational leadership score. The high correlation between these two scores (.82) could lead us to think that these variables are measuring the same construct. However, the regression analyses show that in all cases the LSPS maintains a significant and unique relationship with perceived efficacy of the leader and satisfaction with him/her, even after controlling for its association with transformational leadership. That is, although the two variables tap similar constructs, viewing a leader as a safe haven and secure base is somewhat different from transformational leadership and should be considered in its own right as a factor influencing organization-related feelings, attitudes, and behaviors.

In conclusion, we have initial evidence for the reliability and validity of the LSPS. In Study 2, we continued to explore the validity of the LSPS scale by examining its association with other organization-related variables.

Study 2

The goal of Study 2 was to further validate the LSPS by conducting a confirmatory factor analysis of the scale and examining its association with other organization-related variables. First, we examined the association between the LSPS and the construct of authentic leadership (Avolio, Gardner, Walumbwa, Luthans, & May, 2004). According to Avolio et al. (2004), an authentic leader is one that shows hope, trust, positive emotions, optimism, relational transparency, and a moral and ethical orientation towards his or her subordinates. Therefore, we expected that this style of leadership would be positively associated with perceiving the leader as a security provider. Second, we examined the associations between the LSPS and other relevant organizational behavior variables, such as employee’s identification with the organization, work engagement, and work satisfaction. We expected that when subordinates perceived a leader as providing a safe haven and secure base, they would hold more positive attitudes toward the leader and toward the safe and secure work setting he or she fostered, thereby exhibiting greater identification with the organization and more work engagement and satisfaction.

Method

Procedure and participants. As in Study 1, participants were recruited and interviewed by undergraduate psychology students at a Spanish university, who received practicum credits for their work. Participants, from all over Spain, were asked to evaluate their immediate leaders and several aspects of their organizational life by completing an online questionnaire during February and March 2015. Participants (N = 263, 23.6% males and 76.0% females) were included only if they had been working with their leader for at least for one year (M = 5.50 years, SD = 5.09). Participants’ ages ranged from 21 to 67 years (M = 37.1, SD = 9.02); 74.9 % of the participants had or were studying for a university degree and about 16% had finished high school; of the rest, 6.8% had received professional training and 1.5% had finished compulsory secondary education. Most of participants worked in a private company (62%) or in the public administration (30.8%); for 52.3% of the participants this working environments was big and for 47.7% was medium. Leaders tended to be men (59.7%) while women leaders represented 39.8%.

Instruments. The extent that leaders are perceived as a security provider was assessed with the 15-item LSPS described in Study 1. Authentic leadership was measured with the 13-item Spanish adaptation (Moriano, Molero, & Levy Mangin, 2011) of the Authentic Leadership Questionnaire (ALQ) developed by Walumbwa, Avolio, Gardner, Wernsing, and Peterson (2008). A sample item from this scale is “My leader demonstrates beliefs that are consistent with his/her actions.” Participants were asked to judge how frequently their direct manager or supervisor engaged in specific leadership behaviors on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (frequently, if not always). In the current sample, Cronbach’s alpha for the 13 items was high (.93), allowing us to compute a total score by averaging the items. Higher scores reflect the perception of greater authentic leadership.

To assess organizational identification, we used the Spanish version of the Organizational Identification Scale (OIS; Mael & Ashforth, 1992), which has been employed in previous studies with Spanish samples (Moriano et al., 2011). The scale includes 10 items (e.g., “The success of my organization is my own success”) and participants are asked to rate the extent to which they agree with each item using a 7-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 6 (very much). In the current sample, Cronbach’s alpha for the 10 items was acceptable (.83), allowing us to compute a total score by averaging the items. Higher scores reflect higher organizational identification.

An employee’s work engagement was assessed using the Spanish short version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES-9; Schaufeli, Bakker, & Salanova, 2006). This scale includes 9 items (e.g., “At my work, I feel that I am bursting with energy”) and participants are asked to rate the extent to which they agree with each item using a 7-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 6 (very much). In the current sample, the alpha coefficient for the 9 items was high (.95), allowing us to compute a total score by averaging the items. Higher scores reflect higher levels of work engagement.

General work satisfaction was assessed with an eight-item scale dealing with several aspects of employees’ job satisfaction (e.g., co-workers, work conditions, work climate, and salary). This scale has been used in previous studies with Spanish samples (e.g., Molero, Cuadrado, Navas, & Morales, 2007). Participants are asked to rate their satisfaction with each of the eight work aspects on a 7-point scale ranging from 0 (strongly dissatisfied) to 6 (strongly satisfied). In the current sample, the alpha coefficient for the 8 items was acceptable (.82), allowing us to compute a total score by averaging the items. Higher scores reflect higher levels of work satisfaction.

Results and Discussion

Confirmatory factor analysis. We conducted a confirmatory factor analysis of the 15 items of the LSPS using the PRELIS and LISREL 8.7 programs and obtained an acceptable fit for the existence of a unique factor (see Table 4). Although the root mean square residual (RMR) was not very good (0.21), the rest of the indexes were good (NFI = .99, RMSEA= .072, AGFI = .99, NNFI = .99, CFI = .99). Parsimonious fit indices values were PGFI = 0.74 and PNFI = 0.85. The reliability of the 15-item scale was α = .96.

Associations with other variables. As can be seen in Table 5, in line with our predictions, the more subordinates perceived a leader as a security provider, the more they perceived him or her as an authentic leader and the greater was their organizational identification, work engagement, and work satisfaction.

Table 5 Pearson Correlations between Study 2’s Variables

Note. Diagonal elements in italics are the square root of AVE between the constructs and their indicators.

**p < .01.

In order to explore the unique contribution of the LSPS to subordinates’ organizational identification, work engagement, and work satisfaction beyond the contribution of authentic leadership, we incorporated the two leadership variables (LSPS, authentic leadership) as simultaneous predictors in regression analyses while controlling for several sociodemographic variables – gender, age, education level, time of working with leader (Table 6). In the case of organizational identification, the explained variance of the model was R2 = .11 and only the beta for the LSPS was significant. With regard to work engagement, the R2 was .19 and only the betas for age and authentic leadership were significant. Finally, in the case of work satisfaction, the R2 was .22 and only the beta for authentic leadership was significant. These results show that the LSPS has a direct effect only on organizational identification, whereas authentic leadership has a direct effect on work engagement and satisfaction. As in Study 1, sociodemographic variables made no significant contribution in most of the cases.

Because the LSPS was highly correlated with both work engagement and satisfaction, the regression findings suggest the possibility that authentic leadership may mediate the path from LSPS to work engagement and satisfaction. To test the significance of the mediation we used the SPSS macro PROCESS (Hayes, 2013, v2.16.3). The number of bootstrapping samples was set to 5,000 and the confidence interval to 95% for the indirect effect. As this macro allows only a single outcome, we ran a separate model for each outcome with the same seed command. Results presented in Table 7 suggest that there is an indirect effect of LSPS on both work engagement and work satisfaction through authentic leadership.

Table 7 Mediation Analysis of the path from LSPS to Work Engagement and Work Satisfaction Mediated through Authentic Leadership

Note. Unstandardized regression coefficients (standard errors in parentheses). Effects are significant when the upper and lower bounds of the bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals (CI) do not contain zero.

***p < .001

Overall, the results of Study 2 provided additional evidence for the validity of the new LSPS scale. First, a confirmatory factor analysis, like the exploratory analysis in Study 1, showed that the scale is unifactorial. Second, as expected, the LSPS was positively associated with authentic leadership. Third, as expected, the LSPS was positively correlated with important organizational variables: organizational identification, work engagement, and work satisfaction. We also found that the associations between the LSPS and the variables of work engagement and work satisfaction were totally mediated by the perception of a leader as an authentic leader. This means that perceiving the leader as a security provider leads subordinates to be receptive to the characteristics and behaviors of authentic leadership (e.g., relational transparency, internalized moral perspective, balanced processing, and self-awareness), and these characteristics tend to increase employees’ work engagement and satisfaction.

Study 3

In Studies 1 and 2, we examined the relationships between the LSPS and other organizational variables, including several styles of leadership. In Study 3, we went a step further by examining the psychological processes through which the perception of a leader as a security provider can be related to job burnout – a common organization-related health problem (Maslach, Schaufeli, & Leite, 2001). We propose a model in which employees’ perception of a leader as a secure base enhances their positive affect and decreases their negative affect at work, which in turn reduces the likelihood of job burnout.

According to Maslach et al. (2001), job burnout is a prolonged response to chronic emotional and interpersonal stressors in the workplace and is usually expressed in (a) emotional exhaustion – feelings of being depleted emotionally and physically, (b) cynicism – negative responses to the workplace that frequently lead to depersonalizing the customers or recipients of services, and (c) feelings of incompetence at work. Burnout arises primarily as a result of stress-related processes (Maslach et al., 2001) and affects both individuals (by diminishing physical and mental health) and organizations (by decreasing employees’ motivation and performance). This syndrome is associated with emotional and situational demands (e.g., high workload) along with lack of psychological resources available at the workplace (e.g., low social support) to cope with these demands (Bakker, Demerouti, & Verbeke, 2004).

Previous studies have shown that positive leadership behaviors can alleviate subordinates’ job burnout. For example, in a study conducted with 289 workers in the technological sector, Hetland, Sandal, and Johnsen (2007) found that transformational leadership was inversely associated with job burnout. In other research along these lines, Laschinger, Wong, and Grau (2013) found in a study of 342 nurses that authentic leadership was inversely associated with job burnout. We therefore predicted that subordinates’ perception of their leader as a secure base would also preclude or reduce job burnout.

We expected the contribution of subordinates’ perception of a leader as a security provider to reduce job burnout through the mediation of subordinates’ positive and negative affectivity. There are no previous studies of the possible relationship between the perception of a leader as a secure base and subordinates’ affectivity. However, attachment research clearly shows that more securely attached adults are more able to regulate negative emotions and to experience more frequent and more prolonged episodes of positive affectivity (see Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016, for a review). Several studies using the PANAS scale for assessing positive affect (PA) and negative affect (NA) have found that both attachment anxiety and avoidance in close relationships are negatively associated with PA scores and positively associated with NA scores (e.g., Barry, Lakey, & Orehek, 2007; Wearden, Lamberton, Crook, & Walsh, 2005). Based on these findings, we predicted that subordinates’ perception of a leader as a security provider would be positively associated with positive affect at work and negatively associated with negative affect. We also predicted that these variations in subordinates’ affectivity would be associated with job burnout, with increases in positive affect and decreases in negative affect contributing to less job burnout, and that these variables would mediate the association between the perception of a leader as a secure base and subordinates’ job burnout.

The association between the LSPS and the three components of burnout are predicted to be mediated by PA and NA at work. This means that the perception of a leader as a security provider will lead to an increase in positive emotions at work and a reduction in negative emotions, which in turn will reduce emotional exhaustion and cynicism and increase professional efficacy.

Method

Procedure and participants. As in Studies 1 and 2, participants were recruited and interviewed by undergraduate psychology students at a Spanish university who received practicum credits for their work. Participants, from all over Spain, were asked to evaluate their immediate leaders and several aspects of their organizational life by completing an online questionnaire during January 2017. Participants (N = 263, 36.1% males and 63.9 % females) were included only if they had been working with their leader for at least for one year (M = 4.40 years, SD = 4.76). Participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 64 years (M = 36.2, SD = 10.8); 58.2 % of the participants had or were studying for a university degree and about 13.3% had finished high school; of the rest, 19.8% had received professional training and 8.7% had finished compulsory secondary education. Most of participants worked in a private company (57.8%) or in the public administration (33.8%); for 41.1% of the participants the size of this working environments was big, for 18.3% was medium, and for 40.7% was small.

Instruments. The extent that a leader was perceived as a secure base was assessed with the 15-item LSPS described in Study 1. In the current sample, the alpha coefficient for the 15 items was .93.

To assess work-related emotions we used the Spanish version of a 12-item scale by Warr (1990). This instrument has been validated in Spain by Laguna, Mielniczuk, Razmus, Moriano, and Gorgievski (2016). The scale includes six items tapping positive affect (calm, contented, relaxed, cheerful, enthusiastic, and optimistic) and six items tapping negative affect (tense, uneasy, worried, depressed, gloomy, and miserable). Participants were asked to rate how frequently they experienced these emotions at work in the past few weeks with a 6-point scale ranging from 0 (never) to 5 (all of the time). In the current sample, alphas for the 6 positive affect items and the 6 negative affect items were acceptable (.88 and .78, respectively), allowing us to compute two total scores by averaging the relevant items. Higher scores reflect higher levels of work-related positive and negative affect.

To assess burnout we used the Spanish version of the MBI General Survey (Schaufeli, Leiter, Maslach, & Jackson, 1996), developed by Salanova, Schaufeli, Llorens, Peiró, and Grau (2000). This 15-item scale assesses three dimensions of burnout: emotional exhaustion (e.g., “I feel emotionally drained from my work”), cynicism (e.g., “I have become less enthusiastic about my work”), and professional efficacy (e.g., “I can effectively solve the problems that arise in my work”). Participants were asked to rate how frequently they experienced these feelings and thoughts at work during the previous few weeks with a 7-point scale ranging from 0 (never) to 6 (all of the time). In the current sample, alpha coefficients were acceptable for items tapping emotional exhaustion (.89), cynicism (.83), and professional efficacy (.80). We computed three scores by averaging the relevant items. Higher scores reflect higher levels of emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and professional efficacy.

Results and Discussion

Pearson correlations revealed, as expected, that perception of the leader as a security provider was positively associated with positive affectivity and professional efficacy and negatively associated with negative affect, emotional exhaustion, and cynicism (see Table 8).

To analyze the hypothesized mediational model, we used the SPSS macro PROCESS (Hayes, 2013, v2.16.3). As our model comprises three dependent variables, the entire process was repeated for each of these criteria separately (Table 9). LSPS had significant associations with both positive affect and negative affect in the predicted directions. Moreover, as expected, we found that positive affect was negatively associated with emotional exhaustion and cynicism, and positively associated with professional efficacy, whereas negative affect showed the opposite pattern of associations.

Table 9 Mediation Analysis for LSPS and Burnout (Exhaustion, Cynicism, and Efficacy) through Affect (Positive and Negative Affect)

Note. Unstandardized regression coefficients (standard errors in parentheses). Effects are significant when the upper and lower bound of the bias corrected 95% confidence intervals (CI) does not contain zero.

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Positive and negative affect fully mediated the path from LSPS to emotional exhaustion as well as the path from LSPS to cynicism. However, the path from LSPS to professional efficacy was only partially mediated by positive affect, since both the direct and the indirect effects were significant. Negative affect had a nonsignificant effect. These findings provide empirical support for the mediating role of affectivity in the association between perceiving one’s leader as a security provider and job burnout.

General Discussion

The main idea underlying this research is that the follower-leader relationship can be conceptualized as an attachment relationship and that followers may perceive their leader as a safe haven in times of need and secure base for exploration and thriving. There was theoretical support for this idea in the literature (Mayseless, 2010; Mayseless & Popper, 2007; Popper & Mayselles, 2003) but, as far as we know, this idea had not been empirically tested. We therefore designed a self-report scale tapping the extent to which followers perceive their leader as fulfilling the functions of a security-providing attachment figure within organizational contexts.

Through exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses we found that the new scale is unidimensional and highly reliable. It seems that, although theoretically it is possible to differentiate between different attachment-related functions of a leader, empirically followers tend to perceive these functions as part of a higher-level construct related to the provision of support and security by a leader. For this reason, the scale is called the Leader as Security Provide Scale (LSPS). In future studies, we will continue exploring the factorial structure of the scale, but as it happens with other leadership instruments (e.g., MLQ), sometimes the factorial structure obtained empirically not always replicates the theoretical structure proposed by the authors of the scale. We conducted three studies to examine the utility and the validity of the LSPS. In Studies 1 and 2, we examined the convergent validity of the LSPS by focusing on its associations with scales tapping other styles of leadership. In Study 3, we also examined the contribution of the LSPS to an important organizational behavior variable – job burnout, while examining the involvement of work-related positive and negative emotions in this process.

After conducting our studies, we noticed that Wu and Parker (2017) had examined the role of leader support in facilitating employees’ proactive work behavior. These authors assessed perception of leader support with items taken from existing leadership and management scales. Although valuable, Wu and Parker’s (2017) approach is different from our approach, because our conceptualization of leader support is grounded in attachment theory and incorporates all the criteria that, according to attachment research (e.g., Fraley & Davis, 1997), a leader should fulfill in order to be perceived as a security-enhancing attachment figure (proximity seeking, emotional bond, separation distress, save haven and secure base).

In Studies 1 and 2, we obtained evidence for the convergent validity of the LSPS with transformational and authentic leadership. In line with our predictions, the LSPS was negatively associated with passive-avoidant leadership (Study 1), which involves refusing to take responsibility for followers’ needs and being absent when needed. However, the high correlations between the LSPS and transformational and authentic leadership in Studies 1 and 2 may cast doubts about the usefulness of the new concept. In our opinion, the construct that we introduced in this paper (the Leader as a Security Provider, LSPS) has some important differences with other leadership style constructs. The first is that, unlike the majority of the research in leadership, the LSPS focus on the quality of relationship (bonds) between followers and leaders. This point of view, as Uhl-Bien et al. (2014) point out, is unusual in leadership literature. The second difference with other leadership constructs is that the LSPS has strong theoretical basis in Bowlby’s (1982) attachment theory. This theory was formulated initially to explain the infant-caregiver relationship and subsequently to explain adult personal relationships. In our theoretical introduction, we have tried to justify why it is possible and useful to apply attachment theory to the field of leadership. In our opinion, expanding the focus of attachment theory to include subordinate-leader relationships is another important contribution of our paper. Although it is true that we found high correlations between LSPS and other styles of leadership, we also found that the LSPS contributed significantly to explain subordinate’s perceived efficacy and satisfaction beyond other leadership styles (Study 1) and plays a meaningful role in mediating the association between authentic Leadership and work engagement and work satisfaction (Study 2). Moreover, the average variance extracted (AVE) square root was higher than the correlations between the LSPS and transformational leadership (see Table 2) and authentic leadership (see Table 5), which is as an indication of discriminant validity among these constructs.

Study 3 explored the association between the LSPS and job burnout, a dysfunctional syndrome affecting employees and organizations that is characterized by emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and feelings of incompetence at work. We found that the LSPS was negatively associated with emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and feelings of incompetence. In addition, we found that the LSPS was positively associated with the experience of positive emotions at work, which seemed to mediate the negative association between the LSPS and job burnout. Thus, just as a security-providing parental figure is able to alleviate children’s anxiety and distress in stressful situations, the perception of a leader as a secure base or a safe haven can increase positive emotions at work and reduce feelings of job burnout among employees.

These initial results for the LSPS are encouraging. The scale shows good reliability and convergent, discriminant, and incremental validity. However, this is only a first step in the validation process, and there are several issues that need to be examined in future research. The first is the direction of causality between the LSPS and other measures of leadership styles. We need experimental or longitudinal designs to shed light on this issue. Another important question concerns the organizational context in which employees and managers are immersed. Bowlby (1982) said that the activation of the attachment behavioral system is more probable in times of crisis and distress. This aspect of the theory was not featured in our research, and we expect the importance of the perception of a leader as a security-providing figure would increase in times of crisis or stress. Future studies should examine this issue. It will also be important to examine whether the LSPS is an individual-level or a group-level variable; that is, to what extents do members of a group share a perception of their leader as a security-providing attachment figure?

In sum, we have created and examined a new scale to assess the perception of a leader as a security-providing attachment figure. We believe it is worthwhile to continue to explore this measure, which opens the way to an attachment conceptualization of the follower-leader relationship. We agree with Bresnahan and Mitroff (2007, p. 607), who wrote that “attachment theory could extend the study of leadership into a variety of directions, setting the overarching, elusive concept of leadership on strong theoretical footing. Basing the study of leadership at least partially on a theory that emphasizes how individuals relate to each other and to groups could provide crucial theoretical concepts when looking at relational theories that address leader–follower dynamics”.