Until the 1950s, the study of healthy organizations focused on indicators such as low absenteeism, loyalty, production levels, or industrial safety. However, from the 1950s on, researchers’ approaches began to change. Argyris (1958) defined a “healthy organization” as one that allows optimal human functioning to occur. Working conditions began to be evaluated because they could negatively and positively influence employees’ health (Gómez, 2007).

Following this more positive approach, in their HEalthy & Resilient Organizations (HERO) model, Salanova et al., 2012) defined healthy and resilient organizations as:

those organizations that make systematic, planned, and proactive efforts to improve the processes and results of their employees and organization. These efforts are related to organizational resources and practices, and to the characteristics of work at three levels: (1) task level (e.g., redesign of tasks to improve autonomy, feedback), (2) environmental social level (e.g., leadership), and (3) organizational level (e.g., organizational strategies for the improvement of health, work-family reconciliation) (p. 788).

The HERO model tells us that an organization that invests in healthy organizational practices and resources promotes higher levels of well-being in its employees, which, in turn, leads to better organizational results (Salanova et al., 2012). In sum, it is clear that investing in employees’ health and well-being is synonymous with profitability and competitiveness (Salanova et al., 2018). Based on this model, a healthy employee is also an engaged employee who experiences a positive affective-emotional and psychological state related to his/her work, characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption (Salanova & Schaufeli, 2009). Previous research has shown that providing more job and personal resources at work, i.e., organizational trust (Acosta et al., 2012), team support climate (Torrente et al., 2012), or transformational leadership), is related to a greater probability of having engaged employees. In addition, research has also shown that engagement has important consequences, such as increasing performance and service quality (Salanova et al., 2005; Salanova et al., 2003; Torrente et al., 2012), job satisfaction, and organizational commitment (Llorens et al., 2006).

According to Sonnentag (2003), employees who feel sufficiently recovered from the work stress experienced the previous day have much higher engagement levels the next day, compared to those who do not know how to use their leisure time to recover. Physical exercise (PE) is an activity that can help employees to recover from the stress generated during the workday (Sonnentag, 2001). Currently, PE is considered a valuable resource for improving physical and emotional well-being in companies (Nägel et al., 2015). It is so relevant that even in healthier organizations is adopted as a positive intervention mechanism to promote positive emotional states and increase performance (Nägel et al., 2015).

Although some studies show the effect of PE on physical (e.g., Myers et al., 2015) and psychological well-being (Ströhle, 2009), engagement (Sonnentag, 2003), or emotions (Nägel et al., 2015), there are no studies that explore the impact of PE on the development of different dimensions of a healthy and resilient organization (such as a HERO). A key element of the HERO model (Salanova et al., 2016; Salanova et al., 2012; Salanova et al., 2019) is employees’ perception of organizational practices and resources. With this research we intend to study the role of PE in the HERO model structure for the first time.

Another relevant aspect in applied research is consideration of gender differences. Specifically, in the context addressed in the present study, research results are inconclusive, that is, some studies found gender differences in variables such as job resources, engagement, performance, and PE, (e.g., Maculano et al., 2014; Cifre et al., 2011), whereas other studies found no differences (e.g., Gil et al., 2015; Kredlow et al., 2015). Thus, there is a need to continue with this line of research.

Theoretical Model: The HERO Model

The HERO model is a heuristic and theoretical model that makes it possible to integrate results based on theoretical and empirical evidence emerging from studies on job stress and organizational behavior and from the field of Positive Occupational Health Psychology (Llorens et al., 2009). According to this model, a healthy and resilient organization combines three key components that interact with each other: (1) healthy organizational resources and practices (e.g., autonomy), (2) healthy employees (e.g., efficacy beliefs), and (3) healthy organizational results (e.g., performance). This model proposes that healthy organizational resources and practices are positively related to employees’ well-being and healthy organizational results (Salanova et al., 2012).

The HERO model has been tested in different samples of employees and supervisors, providing evidence for the impact of organizational practices and resources on the development of healthy organizations through their effects on employees’ well-being, using data aggregated at team level and different sources of information (e.g., Salanova et al., 2012; Torrente et al., 2012; Tripiana & Llorens, 2015). However, the present study goes one step further and tests the HERO model but focusing on the effect of employees’ PE. Thus, the invariance of the HERO model is tested in two subsamples of employees depending on the physical activity they engage in: sedentary employees, those who do PE less than three times a week (WHO, 2010), and non-sedentary employees, the rest of the employees.

Job Resources

Job resources are found within the Organizational Practices and Resources component of HERO, and consist of task and social resources that, along with the organizational practices, are oriented toward increasing psychological and financial health at individual, team, and organizational levels (Salanova et al., 2012).Task resources are the closest to the employees because they are related to characteristics of the tasks themselves: clarity of task and job role, autonomy, variety of tasks, and existence of information and feedback about what is done. These resources promote employees’ connection with and pride in their work and their immediate enjoyment. Social resources refer to shared job context and include co-workers and bosses, as well as clients or employees of suppliers, increasing employees’ connections with people with whom they work. Research tells us that positive psychological states such as engagement can be increased and fostered through investments in resources (i.e., personal, task, social, organizational resources) and healthy organizational practices (Salanova & Schaufeli, 2004; Torrente et al., 2012; Tripiana, & Llorens, 2015).

Work Engagement

Work engagement is understood as a positive emotional state related to work and characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption. Rather than a specific and momentary state, engagement is a more persistent cognitive-affective state that is not focused on a particular object, event, or situation. Vigor is characterized by high levels of mental energy at work and the desire to invest effort in the work one is doing, even when difficulties arise. The dimension of dedication denotes high work involvement, along with feelings of significance, enthusiasm, inspiration, pride, and challenge on the job. Finally, absorption occurs when an employee is completely focused on the job, feels like time is flying by, and finds it difficult to disconnect from his/her tasks due to high levels of enjoyment and concentration (Schaufeli et al., 2002).

Although, to date, the study of work engagement has been oriented toward the individual, it can exist as a collective psychosocial phenomenon (Bakker & Leiter, 2010; Salanova et al., 2003). Members of teams and work units interact daily, mutually influencing their levels of work engagement. This means that the overall organization can benefit from a shared state of work engagement, and its maintenance would be a competitive advantage for the organization (Macey & Schneider, 2008).

Previous studies have found that encouraging engagement in organizations has positive effects on both individual and organizational performance. At an individual level, it favors employee performance and service quality (Salanova et al., 2005). At organizational level, effects on team performance (Acosta et al., 2018) and service quality (Salanova et al., 2005) have been found.

Job Performance

In the HERO model, healthy organizational results refer to excellence in products and services and positive relationships between an organization and its intra-organizational environment, such as its employees, and the extra-organizational environment, such as suppliers and distributors, the local community, society in general, and clients, through satisfaction and loyalty. Therefore, employees’ performance would be an indicator of these healthy organizational results. This performance has two dimensions: (1) intra-role dimension, defined as activities related to formal work, which can vary depending on tasks within the same organization, and (2) extra-role dimension, defined as activities that exceed a worker’s job description (e.g., helping co-workers or working outside the usual timetable). These two dimensions correspond to task and contextual performance, respectively (Goodman & Svyantek, 1999).

A large body of scientific evidence confirms the positive relationship between engagement and both intra-role and extra-role performance (Demerouti & Cropanzano, 2010). For example, the study carried out by Halbesleben and Wheeler (2008) with North American employees, their supervisors, and their closest co-workers revealed that engagement helps to uniquely explain variance in performance (after controlling for work engagement). In addition, the study by Salanova et al. (2005) with personnel and clients of restaurants and hotels in Spain showed that organizational resources and engagement were predictors of service climate, which, in turn, was a predictor of performance and, consequently, client loyalty.

Sedentariness vs. Physical Exercise

Undoubtedly, the world has evolved scientifically and technologically. However, this development has had an effect on the physical activity of human beings, especially in developed countries. For millions of years, humans have consumed large amounts of energy in the search for food and survival, but today, particularly in developed countries, energy is widely available, and physical activity is not favored due to factors such as the automatization of factories, transportation systems, or the wide variety of electronic devices in homes that have considerably reduced the physical work performed (Jackson et al., 2003).

Sedentariness is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as ‘less than 30 minutes of regular exercise fewer than three days per week’, and it is associated with non-communicable diseases, but also with other problems such as depression and anxiety (Fox, 1999) or lack of vigor (Lee et al., 2001). PE consists of a variety of planned, structured, and repetitive physical activities carried out to improve or maintain one or more components of one’s physical condition (Acevedo, 2012). According to the WHO, recurrent PE sustained in time leads to a series of physical benefits, such as improvements in cardiorespiratory functions and, therefore, less risk of cardiovascular diseases (Després, 2016; Myers et al., 2015), and reductions in the risk of non-communicable diseases such as depression or anxiety (Ströhle, 2009). Considering the effectiveness of PE at a preventive level, its potential as a strategy for optimizing and promoting well-being has been proposed.

In this study, we define PE as a personal practice and a recovery activity (Sonnentag, 2001). The process of recovering from a workday could be understood as the opposite of the stress process, or as the process through which stressed psychological systems return to their pre-stress levels (Meijman & Mulder, 1998). At a theoretical level, recovery is fundamentally based on two theories: the Recovery-Effort Model (Meijman & Mulder, 1998) and the Theory of Conservation of Resources (Hobfoll, 1998). On the one hand, these theories defend the importance of distancing oneself from the sources of stress in order to recover and return to previous levels (Meijman & Mulder, 1998). On the other hand, they emphasize that there is a motivation to conserve, foment, and process our resources and, therefore, recover any resources that are diminished or exhausted during a stressful situation (Hobfoll, 1998).

When and how a person recovers from the work day can be quite varied. Typically, workers use the vacation period or the weekend to recover from work, but on a daily basis this recuperation can also occur, for example, at work during formal rest periods (Trougakos et al., 2008), when changing from one task to another (Elsbach & Hargadon, 2006), or when the work day ends. This recovery does not necessarily have to involve inactivity. PE, for example, has also been found to contribute to recovery (Sonnentag, 2001; Sonnentag & Natter, 2004). The variety of possible activities would encompass low effort pursuits (e.g., reading, watching television, or just sitting on the sofa), social participation (e.g., going out to dinner with friends or making a phone call), and cognitive (e.g., playing video and/or computer games, learning a new language and/or skill) and physical challenges.

Physical activities stimulate physiological and psychological processes, and so they are beneficial at both physical and mental health levels (Brown, 1990; McAuley et al., 2004). At the physiological level, PE elevates the levels of endorphins (Grossman et al., 1984), serotonin, noradrenalin, and dopamine (Cox, 2002). At the psychological level, many physical activities facilitate mental distraction from job demands (Yeung, 1996). The feeling of mastery and the increase in self-efficacy from performing a physical activity can also aid in recovering from stress (Demerouti et al., 2009; Sonnentag & Jelden, 2009).

Research carried out by Nägel et al. (2015) found that on the days employees did exercise after work, they experienced an improvement in their positive affect and perceived serenity before going to bed. Positive affective states are important antecedents of results related to work and success (Ilies & Judge, 2005; Lyubomirsky et al., 2005; Tsai et al., 2007). Therefore, especially after an exhausting day at work, when affective states could be deteriorated, it is crucial for employees to do activities such as PE in their free time to restore these affects. In doing so, employees will improve their well-being and, thus, be able to perform their work well and efficiently. Along the same lines, Sonnentag (2003) also showed that the level of engagement is positively associated with the degree to which employees recover from physical, mental, and emotional efforts of the previous workday.

In spite of the importance of recovering resources after a stressful workday, and the fact that PE is an important activity in this recovery, few studies have been carried out on this topic. Thus, we aim to analyze the relationship between frequency of PE and levels of well-being, in terms of engagement, and their relationship with performance at work.

Gender Differences

Research on gender differences in the context addressed in the present study is extensive, but also inconclusive, as mentioned above. On the one hand, some studies point to the absence of gender differences in the perception of healthy organizational resources and practices (i.e., work-family enrichment) or engagement (Hakanen et al., 2011) in a sample of dentists. This lack of gender differences has also been found in a meta-analysis performed by Kredlow et al. (2015) on the benefits of regular PE for sleep quality, and in the study by Gil, Llorens, and Torrente (2015), who concluded that gender similitude on a work team does not influence the perception of positive team affects. On the other hand, other studies reveal the existence of gender differences, for example, in the perception of job demands and resources and psychosocial well-being (Cifre et al., 2000; Cifre & Salanova, 2008; Cifre et al., 2011). There are also differences in the pre-disposition toward and use of transformational leadership, which is higher in women (Pounder & Coleman, 2002), or in levels of arousal and sleep time, where women present lower levels of arousal and better sleep quality (Maculano et al., 2014).

The Present Study

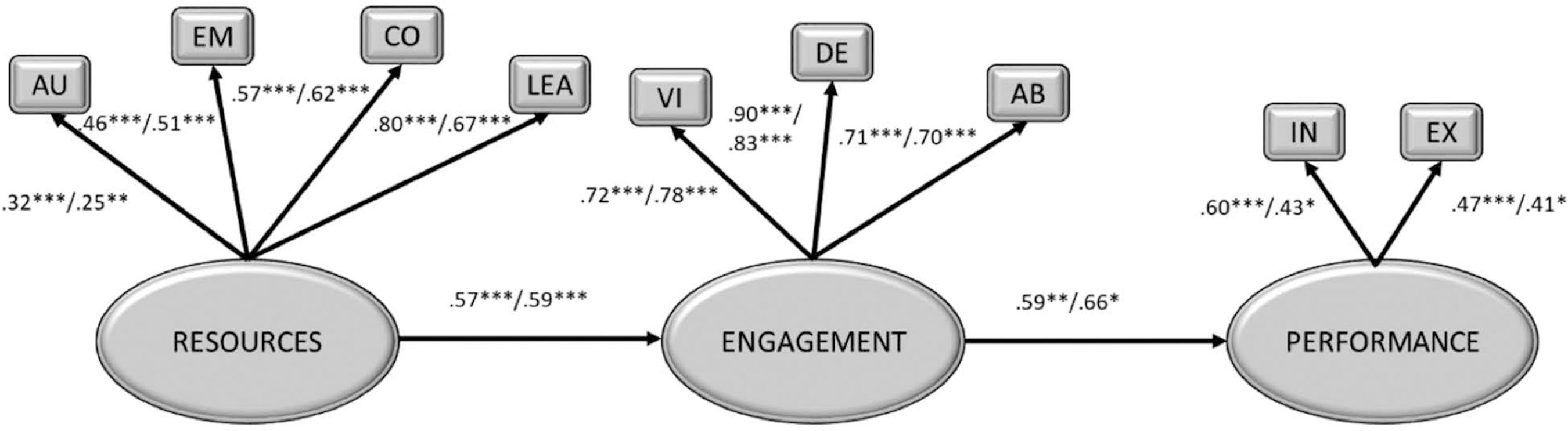

The purpose of the present study is to analyze the relationship between job resources and job performance, taking into account the mediating role of engagement and testing the invariance of the HERO model depending on employees’ PE. Another objective is to find out whether people who engage in PE show a greater perception of resources at work and higher levels of engagement and performance than those who do not. Additionally we attempt to discover if there are differences according to gender and PE. Specifically, the study hypotheses are the following (see Figure 1):

Note. AU = autonomy; EM = empathy; CO = coordination; LEA = leadership; VI = vigor; DE = dedication; AB = absorption; IN = intra-role; EX = extra-role.

Figure 1. Hypothesized Model.

Hypothesis 1: We expect work engagement to fully mediate the relationship between resources and performance, regardless of the physical activity of the employees (sedentary and non-sedentary).

Hypothesis 2: We expect employees who do PE (non-sedentary) to show higher levels of the study variables (resources, engagement, and performance), compared to those who do not (sedentary).

Hypothesis 3: We expect no significant differences to be found between men and women in the study variables (resources, engagement, and performance), without taking into account the PE performed.

Hypothesis 4: We expect the male employees who do PE (non-sedentary) to show higher levels of the study variables (resources, engagement, and performance) than the male employees who do not (sedentary).

Hypothesis 5: We expect the female employees who do PE (non-sedentary) to show higher levels of the study variables (resources, engagement, and performance) than the female employees who do not (sedentary).

Method

Participants and Procedure

The total sample was composed of 319 employees from different Spanish organizations who participated in a research project on active aging. It was a convenience sample, and the data were collected in 2016. Regarding sex, 52% of the employees were men, mean age was 37 years (minimum = 19, maximum = 63, SD = 8.8), and 71% had a permanent contract. This sample was adequate for performing structural equation analyses, given that it exceeded the minimum of 148 observations for a statistical power of .50 and 50 degrees of freedom (MacCallum et al., 1996).

To address the study objectives, the sample was divided into two groups according to the PE they usually do. To perform this classification, WHO’s definition for sedentariness was used, where ‘sedentariness’ means doing less than 30 minutes of PE fewer than three days a week. Using this criterion, the total sample was divided into two subsamples: ‘sedentary’, corresponding to employees who did PE less than three days a week, and ‘non-sedentary’, corresponding to employees who worked out three or more days a week. The sedentary sample consisted of 156 participants whose mean age was 37 years (minimum = 20, maximum = 60, SD = 8.5); 52% were men, and 74% had permanent contracts. The non-sedentary sample consisted of 163 participants whose mean age was 36 years (minimum = 19, maximum = 63, SD = 9.1); 52% were men and 68% had a permanent contract.

With regard to the procedure, the sample filled out the questionnaire in its online format after each firm’s management had given its consent. To do so, participants were provided with a personal access code and the link to the questionnaire. Confidentiality of data was guaranteed at all times.

Measures

The variables proposed were from the HERO model, whose scales and their relationships have been validated by Salanova et al. (2012). The present study will evaluate the relationships among the three basic components of the HERO model: healthy organizational practices and resources (specifically, resources such as autonomy, empathy, coordination, and leadership), healthy employees (engagement: vigor, dedication, and absorption), and healthy organizational results (performance). Variables were measured with previously validated scales and reworded using “teams” as a reference (Salanova et al., 2012). A Likert-type scale from 0 (never) to 6 (always) was used. The variables used are described below.

Job resources. Four resources were evaluated with eight items (α = .81): (1) autonomy (Jackson et al., 1993), one item: ‘In my job, I determine when to start, when to finish, and the order in which I do my tasks’; (2) empathy, one item: ‘I try to ‘put myself’ in the other person’s place (co-workers, bosses, clients) to know how s/he feels’; (3) coordination (Salanova et al., 2011), one items, e.g., ‘We coordinate with each other to do the job’; and (4) leadership (Rafferty & Griffin, 2004), five items: ‘She/he encourages me to view changes as situations full of opportunities’.

Work engagement. This was evaluated with the reduced version (three items; α = .81) of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (Schaufeli et al., 2017), which evaluates three dimensions: (1) vigor, one item: ‘I feel strong and vigorous when doing my job’; (2) dedication, one item: ‘I feel excited about my job’; and (3) absorption, one item: ‘I am immersed in my work’.

Performance. This was evaluated with two items (r = .22, p < .001) referring to two key dimensions: (1) extra-role performance (Goodman & Svyantek, 1999), one item: ‘I perform functions that are not required by the contract but improve the functioning and well-being of the organization’; and (2) intra-role performance (Goodman & Svyantek, 1999), one item: ‘I fulfill the functions and tasks my job requires’. This measure was validated by Salanova et al. (2012).

Physical exercise. This was evaluated with one behavioral item that refers to the frequency with which the participants engage in PE each week: ‘How many days a week do you do physical exercise?’ Employees who did PE less than three times a week were classified as sedentary (WHO, 2010), whereas the rest were classified as non-sedentary.

Data Analysis

First, analyses were conducted of the internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha), descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations), and internal correlations of variables considered in the study, using IBM SPSS Statistics 23.0 statistical packet. Second, the Harman one-factor test was performed (see Podsakoff et al., 2003), using the AMOS 23.0 statistical packet to test common variance bias.

Next, multigroup structural equation Models (SEM) were carried out using the AMOS 23.0 program to test the invariance of the hypothesized model simultaneously in both samples (sedentary n = 156 and non-sedentary n = 163). Three models were tested (James et al., 2006): (M1), full mediation model, which proposes that engagement fully mediates the relationship between job resources and workers’ performance; (M2), partial mediation model, which proposes the mediation of engagement between job resources and workers’ performance, and a direct relationship between job resources and performance. In addition, MacKinnon et al.’s (2002) mediation test was used to test the mediator effect of engagement between job resources and performance; and M3, completely constrained model, which proposes that all the model relationships are equal in both samples.

The maximum likelihood method was selected as the estimation procedure because we did not find any normality violations (i.e., skewness index smaller than 2, kurtosis index smaller than 10; Weston & Gore, 2006) of the study variables. We calculated the absolute and relative goodness of fit indexes (Marsh et al., 1996): chi-squared index (p > .05), relative chi-squared index (chi-squared/gl; up to 5.0), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker- Lewis index (TLI), and incremental fit index (IFI). Values below .08 indicate a good fit for RMSEA (Brown & Cudeck, 1993) and values above .90 indicate a good fit for the rest of the indexes (Hornung & Glaser, 2010; Hoyle, 1995). Moreover, Akaike’s information criterion (AIC; Akaike, 1987) was calculated to compare non-nested comparative models; the lower the AIC, the better the fit.

Additionally, multiple analyses of variance (MANOVA) were performed with the IBM SPSS Statistics 23.0 program to test the existence of significant differences in the study variables (resources, engagement, and performance), depending on: (1) PE (sedentary and non-sedentary employees), (2) gender (women and men), and (3) PE and gender (sedentary men vs. non-sedentary men and sedentary women vs. non-sedentary women).

Results

Descriptive Analyses and Harman’s Test

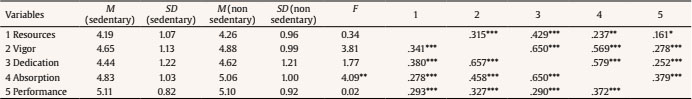

Table 1 shows the means, standard deviations, and inter-correlations among the study variables in the two samples. The correlation analyses reveal that the variables are positively related in the two samples (sedentary r mean = .40, non-sedentary r mean = .38) (see Table 1). Furthermore, the results show that all the scales meet the reliability criterion proposed by the scientific research (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994): resources (α = .81), engagement (α = .81), and performance (r = .21, p <.001).

Table 1. Descriptives and correlations between the variables among sedentary and non-sedentary workers

Note.The correlation is significant at *p <.05 or **p < .01, ***p < .001 level. Below the diagonal appear the correlations of the sedentary group. Sedentary (n = 156) and non-sedentary (n = 163). M = mean, SD = standard deviation, F = multiple analysis of variance.

Second, the results of the one-factor Harman’s test (Podsakoff et al., 2003) revealed a poor fit to the data, χ2(54) = 188.036, RMSEA = .08, CFI =.79, TLI = .72, IFI = .79. Moreover, following the recommendations of Podsakoff et al. (2012), the questionnaire had different headings to differentiate its distinct parts. Common method variance bias did not seem to affect the study data. Therefore, we can attribute the variance in the variables to the psychosocial constructs being evaluated, rather than to the evaluation method.

Model Fit: Multigroup Structural Equation Models

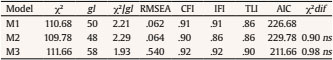

Table 2 shows the results of the SEM models of the relationships between job resources, work engagement, and performance. The model has one exogenous variable (resources) and two endogenous variables (engagement, with its dimensions of vigor, dedication, and absorption, and performance). All the scales were treated as latent variables. Job resources had four indicators, engagement had three, and performance had two.

Table 2. Fit Indexes for the Multigroup Structural Equation Models for the Sedentary and non-Sedentary Samples.

Note.χ2 = chi = square; gl = degrees of freedom; relative chi-square; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; CFI = comparative fit index; TLI = Tucker-Lewis index; IFI = incremental fit index; AIC = akaike information criterion; dif. = difference, ns = non significant. M1 Full mediation model; M2 Partial mediation model; M3 Completely constrained model. Sedentary (n = 153) and non-sedentary (n = 163) samples.

The results of the SEM indicate that the hypothesized model M1, full mediation model, where engagement fully mediates between job resources and workers’ performance, χ2(50) = 110.68, RMSEA = .062, CFI = .91, TLI = .86, IFI = .91, AIC = 226.68, fits slightly better than M2, partial mediation model, χ2(48) = 109.78, RMSEA = .064, CFI = .90, TLI = .86, IFI = .86, AIC = 229.78, although there are no statistically significant differences between the two models with regard to χ2, ∆χ2(2) =. 09, ns. However, the results favor M1, full mediation model, given that: (1) the fit indexes are better in M1, full mediation model, and (2) the direct relationship between resources and performance included in M2, partial mediation model, is not statistically significant. Therefore, these data support M1, full mediation model. Thus, resources are significantly and positively related to performance through engagement.

Furthermore, using the coefficient product method by MacKinnon et al., (2002), in M1, full mediation model, all the requirements are met in both subsamples. For the sedentary employees: (1) job resources are positively and significantly related to work engagement (mediator variable), α1 = .73, p < .01; (2) work engagement is positively and significantly related to performance, β1 = .29, p < .01; and (3) the mediation effect is positive and statistically significant, α1β1 = .21, p < .01. Second, for the non-sedentary employees: (1) job resources are positively and significantly related to work engagement (mediator variable), α2 = .92, p < .01; (2) work engagement is significantly and positively related to performance, β2 = .39, p < .01; and (3) the mediation effect is positive and statistically significant, α2β2 = .36, p < .01. These results show that work engagement fully mediates the relationship between job resources (autonomy, empathy, coordination, and leadership) and performance in both groups, with a direct relationship between resources and performance of τ1 = .08, p = .41 and τ2 = -.05 p =.79 for sedentary and non-sedentary employees, respectively.

Therefore, using SEM and the MacKinnon et al.’s (2002) method, the results provide evidence supporting M1, full mediation model, in both subsamples, and they also provide evidence for the invariance of the model, regardless of the employees’ PE, thus supporting Hypothesis 1. Figure 2 shows the graphical representation of this final model. The manifest variables have factorial weights ranging from .32 to .90 in the sedentary group, and from .25 to .83 in the non-sedentary group. Second, a review of the regression weights for M1 reveals that, as expected, resources are positively and significantly related to engagement, β = .57, p < .01, R2 = 33% and β = .59, p < .01, R2 = 35% for the sedentary and non-sedentary groups, respectively. In addition, engagement, in turn, is positively and significantly related to performance, β = .59, p < .001, R2 = 35% and β = .66, p < .001, R2 = 44% for sedentary and non-sedentary participants, respectively.

Figure 2. Structural Model in two Samples, Sedentary (n = 156) and non-Sedentary (n = 163).Note. AU = autonomy; EM = empathy; CO = coordination; LEA = leadership; VI = vigor; DE = dedication; AB = absorption; IN = intra-role; EX = extra-role. All the standardized coefficients are significant at p <.05. The data to the left of the bar correspond to the sedentary group and those on the right to the non-sedentary group

Additionally, in order to discover whether there are differences in the estimations of the parameters in the two samples, sedentary and non-sedentary, tests of equality of covariances and factorial weights were performed, establishing constraints in the parameters corresponding to the factorial weights (Byrne, 2001). M3, completely constrained model, assuming the equality of the factorial weights of the three latent factors in both samples, obtains a fit that is not significantly different from the data used to compare the free model (M1, non-constrained model, expressed as ∆χ2 = 0.98, ns). In conclusion, the results of the multigroup confirmatory factorial analyses support the model’s invariance, regardless of the PE done by the employees. These results support Hypothesis 1.

Next, MANOVA were performed. First, the groups (sedentary and non-sedentary) were used as the independent variable, and the rest of the study variables (resources, vigor, dedication, absorption, and performance) as dependent variables. The results showed significant differences between the sedentary and non-sedentary employees. The non-sedentary employees showed significantly higher levels of empathy, F(1, 312) = 6.61, p < .05, and absorption, F(1, 315) = 4.09, p < .05, and they also tended to show significantly higher levels of vigor, F(1, 316) = 4.28, p < .052, compared to employees who did not do PE. These results partially support Hypothesis 2.

Second, with regard to gender (as independent variable), the results showed significant differences in favor of women on empathy, F(1, 366) = 7.94, p < .01, mean for women = 4.77, mean for men = 4.37; and performance F(1, 314) = 7.62, p < .05, mean for women = 5.24, mean for men = 4.97. Therefore, Hypothesis 3 is not supported.

Third, MANOVA were performed with PE and gender (sedentary men vs non-sedentary men and sedentary women vs non-sedentary women). The results showed that non-sedentary men have more empathy, F(1, 164) = 7.62, p < .01, (mean for non-sedentary men = 4.82, mean for sedentary men = 4.68), and more vigor, F(1, 165) = 4.12, p < .05, mean for sedentary men = 4.78, mean for non-sedentary men = 4.66, than sedentary men. These results confirm Hypothesis 4. In the case of women, no significant differences were found between those who did PE and those who did not. The results do not confirm Hypothesis 5.

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to evaluate the relationship between job resources and job performance, taking into account the mediating role of engagement and testing the invariance of the HERO model, depending on the employees’ PE. We expected that (1) work engagement would fully mediate the relationship between resources and performance, regardless of the employees’ physical activity (sedentary and non-sedentary), and (2) that the employees who do PE (non-sedentary) would show higher levels of the study variables (resources, engagement, and performance) than those who do not (sedentary).

The results of the SEM showed that the relationship between job resources and performance perceived by employees is fully mediated by engagement, both in the group that works out (non-sedentary) and in the group that does not (sedentary). Moreover, this model is equivalent in both samples, which gives greater validity to the model. Therefore, the results suggest that team’s resources (related to the task and social) are positively related to the positive psychological state of work engagement, which, in turn, is related to performance, regardless of whether an employee works out or not, thus showing the invariability of the HERO model. Specifically, the results show that all the employees (whether or not they do PE) who perceive that the organization invests in positive resources, such as coordination, leadership, empathy, and autonomy, present higher levels of engagement. This means that higher levels of vigor, dedication, and absorption are related, in turn, to one of the organizational results par excellence, performance at work. This performance involves tasks that are consistent with the employment contract and tasks that involve going the extra mile for the organization. These results support Hypothesis 1.

These findings are consistent with previous research showing positive relationships between resources, engagement, and performance when these variables are measured at individual (e.g., Tripiana & Llorens, 2015) and collective (e.g., Salanova et al., 2012; Torrente et al., 2012) levels. Furthermore, they make a novel contribution by showing that, independently from employees’ PE, organization’s investment in resources has beneficial effects on both sedentary and non-sedentary employees.

Although the model is invariant depending on employees’ PE (as expected), significant differences were obtained in the levels of some study variables. It is interesting to note that, as expected, employees who do PE (non-sedentary) show higher levels on one of the resources (i.e., empathy) and on absorption (the third dimension of engagement), compared to sedentary employees. It seems that employees who usually work out are more capable of putting themselves in someone else’s place (co-workers, clients), and time flies by for them at work, thus partially supporting Hypothesis 2.

It was also interesting to find significant differences between men and women because we did not expect to find gender differences in the study variables. Differences were observed in the variables of empathy and performance in favor of women. It seems that women are more empathetic and obtain higher results on their job tasks than men. Thus, Hypothesis 3 was not supported. As we mentioned in the introduction, there is evidence both for and against the existence of gender differences. In this case, these results coincide with the line of studies by Cifre et al. (2000), Cifre and Salanova (2010), and Cifre et al. (2011) in that they show differences between men and women in perception of job demands and resources and psychosocial well-being.

Finally, regarding the last two hypotheses, where we expected to find differences between sedentary and non-sedentary groups, within the group of men (Hypothesis 4) and within the group of women (Hypothesis 5), the results were different for the two subsamples. In the group of men, significant differences were found in the variables of empathy and vigor. Men who do PE are more empathetic and vigorous at work than sedentary men, which supports Hypothesis 4. However, within the group of women, no significant differences were found between women who do PE and those who do not. These results do not provide evidence for Hypothesis 5.

Hypotheses 4 and 5 (as well as Hypothesis 2) aimed to demonstrate that considering PE as a way to recover from work stress (Sonnentag, 2001; Sonnentag & Natter, 2004) and improve positive emotions (Nägel et al., 2015) could help to increase the perception of job resources, work engagement (Sonnentag, 2003), and job performance. The results show that there are differences in the population in general and in a group of men, but not when sedentary women are compared to non-sedentary women.

In other words, regarding the role of PE in workers’ well-being, we found that non-sedentary people in general are more empathetic and more absorbed in their job tasks, and men, in particular, are also more vigorous at work. These results follow along the lines of studies that relate PE to an improvement in positive affect and perceived serenity (Nägel et al., 2015) or work engagement (Sonnentag, 2003).

Theoretical and Practical Implications

The present study makes both theoretical and practical contributions. At a theoretical level, the study extends knowledge about the HERO model, especially about the mediator role of work engagement in the relationship between healthy organizational resources and job performance. The results provide evidence about the HERO model, considering that perception of resources at work leads to engagement and better performance on tasks defined in job role and tasks that pursue a better work environment, regardless of PE regular practice.

From a practical point of view, the results provide evidence for implementing intervention strategies designed to develop engagement and performance at work and implement positive practices. Specifically, the results indicate that, in order to increase work engagement, it is necessary to activate intervention strategies that facilitate the development of resources (both task-related and social). This can be achieved by fostering employees’ autonomy in decision-making at work, co-workers’ coordination when performing tasks, the capacity to put yourself in another’s shoes (co-workers, clients), and the development of positive leaders. To do so, this intervention should focus on the organizational level, for example, by carrying out periodic evaluations to optimize company’s levels of healthy organizational resources, or activities to foster leadership skills in order to develop positive leaders. These interventions in resources would allow organizations to benefit from employees who are more engaged and more involved in their work, which would translate into improvements in job performance. Furthermore, the study also indicates the relevance of fomenting employees’ PE because employees who work out are more empathetic and engaged, in terms of absorption, compared to sedentary employees. Finally, the study showed that if organizations want to promote empathy and vigor at work in men, they can adopt the strategy of favoring PE.

Study Limitations and Future Research

The present study has several limitations. First, a convenience sample was used, which limits the generalization of results. However, data were collected in a real context, including workers from different labor contexts. A second limitation of the study is that it has a cross-sectional design. This type of study captures inter-individual variation and does not pay attention to intra-individual aspects (e.g., Molenaar, 2004; Molenaar & Campbell, 2009). Taking into account the type of variables in our study, which vary at individual level, we should choose methods that provide adequate information about them (Navarro et al., 2015). However, in studies like this one that analyze invariance and gender differences, it is sufficient to carry out a cross-sectional study. Future studies should include longitudinal designs and diary studies in order to test PE effects on stress recovery and, thus, on employees’ engagement the next day.

Finally, there are several limitations related to the measurement of the job performance variable. First, this variable was evaluated with self-reported measures. According to Scullen et al. (2000), this type of evaluation of this construct would have considerably less validity than evaluations by supervisors or peers. However, the same authors also point out that self-report provides valuable information that is not available from other perspectives. In addition, multiple analyses of variance in a sample made up of 162 work teams (162 supervisors and their 1,135 employees) were computed to verify the validity of self-report performance measures based on employees’ perceptions. Results showed that there are no significant differences in the performance variable when it is assessed by employees or supervisors. Thus, it seems that an employee’s perception can be used to measure performance. Other limitations are, on the one hand, the number of dimensions used in the study. According to the review carried out by Koopmans et al. (2011), the dimensions of the work performance construct are task performance, contextual performance, adaptive performance, and counterproductive work behavior. In this study, we only included the first two because the instrument we used only took these two dimensions into account. On the other hand, the use of only two items is also a limitation since, according to Lloret-Segura et al. (2014), the minimum number of items recommended for a sample of 319 subjects is 3-4. However, there are different studies whose variables (satisfaction, work engagement) have been evaluated successfully with only one item (Nagy, 2002; Schaufeli et al., 2017). This is an increasingly common practice when advising companies that ask for short versions of questionnaires. Future studies should take into account the limitations related to this variable by trying to address all the dimensions of the construct, using an appropriate number of items for the sample, and collecting information from several informants.