Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Enfermería Global

versión On-line ISSN 1695-6141

Enferm. glob. vol.17 no.52 Murcia oct. 2018 Epub 01-Oct-2018

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/eglobal.17.4.296021

Originals

Evaluation of nursing diagnoses accuracy in a university hospital

1 Residente de Enfermería del Programa de Residencia en Enfermería en la Especialidad de Gerenciamento de Clínica Médica y Quirúrgica. Universidad Estadual del Oeste do Paraná . Cascavel, Paraná, Brasil. thaisvbugs@yahoo.com.br

2 Enfermera. Doctora en Ciencias. Professora adjunta da Universidad Estadual del Oeste do Paraná (Unioeste). Cascavel, Paraná, Brasil.

3 Enfermero. Alumno de doctorado de la Universidad Estadual de Maringá (UEM). Docente colaborador de la Universidad Estadual del Oeste do Paraná (UNIOESTE), Cascavel, PR, Brasil.

4 Enfermera. Doctora en Ciencias. Profesora adjunta de la Universidad Estadual del Oeste do Paraná (Unioeste). Cascavel, Paraná, Brasil.

The study aimed to evaluate the degree of accuracy of the nursing diagnoses of patients hospitalized in a university hospital. This is a documentary, cross-sectional and retrospective research with quantitative analysis. Data were collected from records of patients hospitalized in the neurology sector of a teaching hospital in the western region of Paraná, Brazil. 292 patients’ records were evaluated and after the analyses of inclusion and exclusion criteria, 12 (4.1%) were part of the study. Nineteen nursing diagnoses were identified, documented 94 times. The evaluation of the accuracy of the nursing diagnoses was done using EADE-2. Most of nursing diagnoses (n = 88, 93.6%) were evaluated as highly accurate. The most frequent degree of accuracy was 13.5 (n = 87; 92.6%) and the mean accuracy was 12.9, with a variation from 2 to 13.5. It is concluded that the nursing diagnoses analyzed were highly accurate, but it's notorious the lack of nursing process at the institution studied.

Key Words: Nursing Diagnosis; Nursing Process; Teaching Hospitals

INTRODUCTION

By means of Nursing Care Systematization (NCS) it is possible to carry out the Nursing Process (NP) in the nurse’s clinical practice. The NP is a systematic work method that guides the nursing professional care, consisting of five steps: data collection, nursing diagnosis, planning, implementation and evaluation of nursing1)(2 .

To be effective, the NP must be structured based on a theory of nursing, being essential the use of a scientific framework so that theory and the concepts are propagated in the clinical practice of nursing3 . In these terms, the completion of NP gives greater security to offer assistance to the users, leads to higher quality actions and promotes autonomy nursing professionals, combining the technical, scientific and human knowledge of professional nurses in assistance3 .

The application of a work methodology develops a professional aptitude for planning activities and for care management, providing greater clarity to their actions4 .

The application of the methodology of work develops professional aptitude for planning activities and for the management of care, providing greater clarity of their actions4 .

The identification of nursing diagnoses (ND) is held in the second phase of the NP and is characterized as the clinical interpretation of the users’ responses to actual or potential health problems. Based on the ND listed, the nursing interventions (NI) are selected to achieve the desired results for which the nurse is in charge5 .

The completion of the NP by the nurse promotes communication between the nursing staff and the multidisciplinary team, providing elements that contribute to increasing the quality of health care6 .

The effective communication between the nursing staff occurs through standardized languages that aim to: promote improvements in the quality of the assistance, facilitate the documentation of NP and NI proposed, and assess their effectiveness during care7 .

The development of nursing knowledge indicated that people’s responses to the processes of life and health problems can naturally be misinterpreted, because assessing the reactions of individuals is a complex task8 . The interpretations of the nurses on the responses of individuals are subjective, which can end up in less accurate ND9 .

In terms of definition, a diagnosis is considered highly accurate when it reflects the evaluated patient real characteristics10 . The accuracy of ND is evaluated based on the patient's clinical data. Diagnostic reasoning skills are important to formulate ND with higher degrees of accuracy11 .

It is important to note that the accuracy of a ND is a continuous property, which gives the possibility to be more or less accurate12 .

The concern with the ND accuracy listed is recent. In general, in their daily working, nurses end up exploring superficially the clinical manifestations that indicate ND or valuing evidence that do not correspond to the real needs of the patient12 .

Based on accurate clinical interpretations, it is possible to prescribe appropriate nursing care to achieve desirable results. However, when the diagnoses listed are not accurate, the care provided to the patient may be neglected, and can result in assistance damage8 .

In this context, knowing the accuracy degree of the ND listed is important to assist in the evaluation of diagnostic reasoning of nurses working in the institution. The objective of this study was to evaluate the accuracy degree of the ND of the patients in a university hospital.

METHODOLOGY

This is a document research, transversal and retrospective, with quantitative data analysis. This study is part of a larger study entitled Systematization of nursing care: implementation in the clinical practice at a teaching hospital13 . The research was approved by the Research Ethics Committee (CEP) at the University of West of Paraná-UNIOESTE, CAAE: 19704613.1.0000.0107, opinion No. 1,025,721, of 16 April 2015.

The study was carried out in a university hospital of Parana countryside, southern Brazil, who works exclusively with the Unified Health System (SUS), covering various specialties. It has 210 beds, including hospitalization beds, outpatient beds, specialties ambulatory, Surgical Center (SC), Obstetric Centre (OC), adult Intensive Care Unit (ICU), Pediatric Intensive Care Unit, Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, Intermediate Care Unit (ICU) and Emergency Room (ER).

The data were collected from medical records of patients admitted in the Neurology department, containing 12 beds, both clinical and surgical. We selected that sector by being one of the only critical hospitalization sectors that carried out the NP on the electronic patient record (EPR) in the period in which the study was done.

We evaluated medical records of neurological patients admitted in that sector during from 01/01/2014 to 12/31/2014. We opted for this period because it was the last year in which the NP was carried out in the sector, given that the institution goes through a process of technologic readjustment of NP.

The criteria to include the records in the study were:

1) Being of neurological patients, clinical or surgical, in the not critical inpatient unit;

2) Being of patients admitted from 01/01/2014 to 12/31/2014.

The exclusion criteria were:

3) Being of patients under 12 years old;

4) Not having ND record arising from the patient’s evaluation;

5) Not having authorization of the nurses who did the ND records that would be assessed, since all the nurses who worked in the department in the period stipulated for the study were consulted on the interest to participate in the research, authorizing the analysis of ND recorded in medical records through the signature of an informed consent (TFCC).

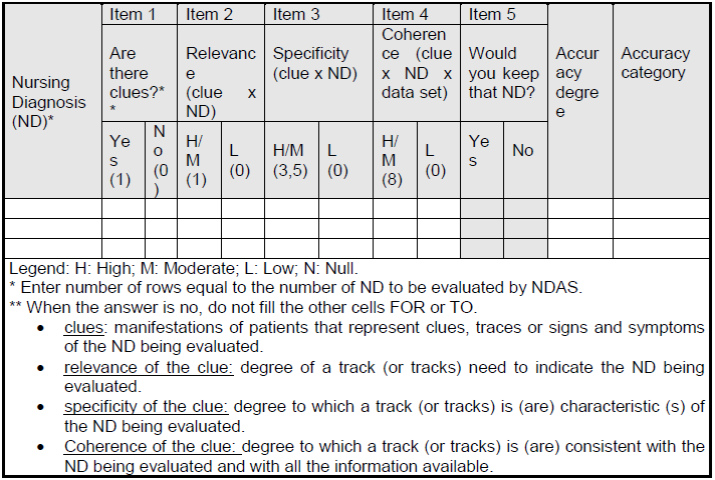

We agreed to evaluate the first ND record in the medical records, regardless the patient’s hospitalization length. In this respect, the evaluation of the ND accuracy was done through an instrument entitled: Nursing Diagnosis Accuracy Scale- version 2 (NDAS-2), as evidenced in Figure 1 .

NDAS-2 was designed to assess the degree to which a diagnostic statement is supported by clinical data of the patient12 . To determine the degree of diagnostic accuracy by NDAS-2, each ND listed by a nurse should be assessed individually based on the set of “clues” contained in the anamnesis records and the physical examination of the patient12 .

The ND accuracy measured by NDAS-2 can be considered a quantitative or qualitative variable. To use the variable as quantitative, we considered the general score of 0 (zero) to 13.5 indicated as “accuracy degree” and to use the variable as qualitative, we considered the four “accuracy categories”12 .

To apply the NDAS-2 every diagnosis must be entered in the first column of the scale named “nursing diagnoses” and should be evaluated if there are any clues to indicate ND under evaluation (item 1: scores 1 or 0); if the existing clue is relevant to indicate ND (item 2: scores 1 or 0), if the existing clue is specific to indicate ND (item 3: scores 3.5 or 0) and if the clue is coherent with the ND and with the patient’s clinical data set (item 4: scores 8 or 0 points). After these four evaluations, the researcher can judge whether it is appropriate or not to keep the ND listed by the nurse (thinking character item, does not score); This application of NDAS-2 was done individually by the searcher.

After, the scores of each assessment are summed up, obtaining a final score that indicates the accuracy degree and the respective accuracy category (0: null accuracy; 1: low accuracy; 2, 4.5 and 5.5: moderate accuracy; and 9, 10, 12.5 and 13.5: high accuracy).

In the present study the application of NDAS-2 was made concurrently by two researchers, who by consensus, indicated the values of each item evaluated.

Analysis of ND accuracy in study was carried out from April to July 2016. The data were released on spreadsheets in Microsoft Office Excel, version 2010. After that, descriptive analysis of the data on proportion measures was done.

RESULTS

After the assessment of exclusion criteria, of 292 (100%) medical files reviewed, only 12 (4.1%) were part of the study sample.

With respect to patients who had their records of ND evaluated, eight were male (n=8; 60%); with an average age of 42.6 years old with variation of 15 to 66 years old; traumatic brain injury (TBI) was the most frequent cause of neurological injury (n=7; 58.3%); the average time between hospitalization and the first record of ND (clues and diagnostics) in the EPR was eight days with a variation of 1 to 45 days.

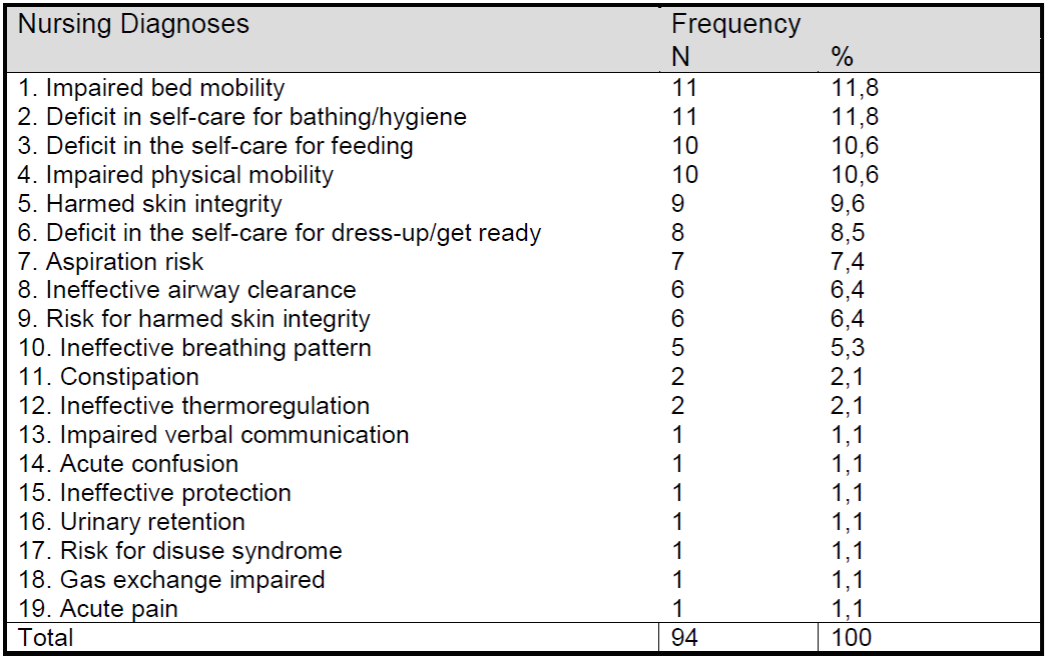

By analyzing the records of neurological patients, it was possible to identify 19 (100%) diagnostic labels, which were set out 94 times. The average ND per patient was 7.8 ND, with not less than three and no more than 12 ND.

Table 1 shows the diagnostic labels identified in the study, with their respective frequencies.

Table 1 Nursing diagnoses of neurological patients admitted in a teaching hospital (N=19). Cascavel-PR, 2016

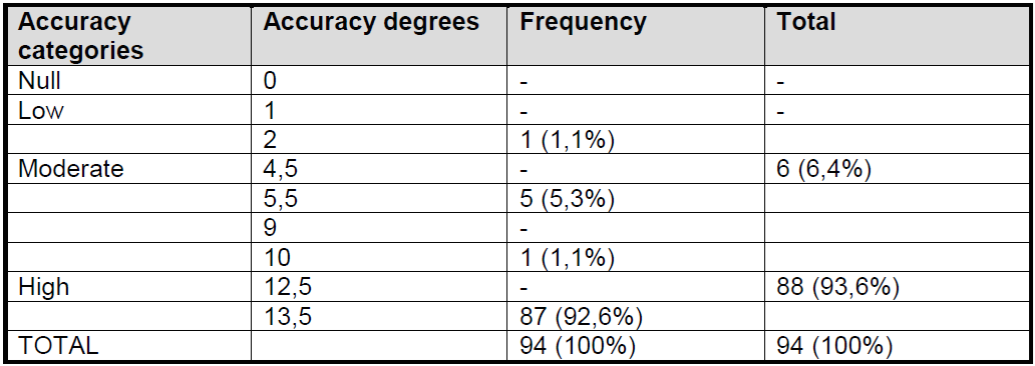

Table 2 shows the accuracy degree of each ND identified in the study, with their respective frequencies.

Table 2 Accuracy of diagnostic labels identified in neurological patients in a teaching hospital (N=94). Cascavel-PR, 2016

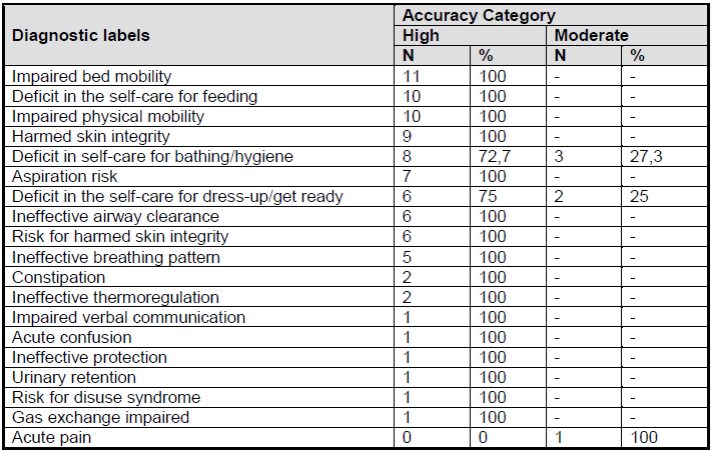

Table 3 shows the accuracy of nursing diagnoses frequency into categories and in degrees.

DISCUSSION

Of the 292 (100%) neurological patients who had their medical records evaluated, the NP was done in only 12 patients (4.11%). Despite of NP being an exclusive activity of a nurse in accordance with the law of the nursing professional practice (Law No. 86/7,498) and in the COFEN resolution number 358/2009 (which repealed the Resolution 272/2002), we can see that, in general, this practice has not yet been effectively deployed in health units which provide nursing care14 . In the present study, the nurses’ lack of adherence to existing national rules that determine the application of NP can be due to the fact that hospital is restructuring the NCS institutionally13 .

The average time between hospitalization and the first record of ND in the EPR was eight days, with a variation of one to 45 days. This contrasts to the literature, since it is recommended that the nurse do the initial assessment of the patient in the first 24 hours of hospitalization15 .

The study identified that TBI (n=07; 58.3%) was the cause of the most common neurological injury, affecting predominantly male patients (n=8; 60%), ranging in age from 40 to 49 years old (average of 42.6 years). These results are consistent with the findings in the literature16 that investigated the epidemiology of TBI in Brazil. This study identified that men between 21 and 60 years old were also the most affected by the injury.

During the analysis of the medical records, 19 diagnostic labels (100%) listed 94 times were identified. The average of ND per patient was 7.8 diagnosis, which is similar to the result found in a study developed in the northeast of the country with patients affected by stroke, who identified an average of 6.7 ND per patient17 . Similarly, in a study developed in São Paulo, held in a unit of medical and surgical clinic, the average ND amounted to 7.3 diagnosis per patient18 .

Of 19 (100%) diagnostic labels identified, 16 (84.2%) were classified as being of “Diagnosis with focus on the problem” and three (15.8%) were classified as being “risk diagnosis”5 .

According to NANDA-I, the diagnosis with focus on the problem are related to “the unwanted human response to health/life processes that exist at the moment”. On the other hand, the risk diagnosis corresponds to a state of “vulnerability to develop in the future an undesirable human response to health/life process”5 . A study developed with hemodialysis patients held in northeastern Brazil, stands out the notoriety of the role played by nurses in specific actions to prevent that risk diagnoses become real19 .

It is important to note that the nurse must act to avoid that risk diagnoses become real diagnoses. The classification of risk diagnoses intensifies the importance of using NP in risk management, in which is fundamental to play actions on prevention and health promotion20 .

Of 19 (100%) diagnostic labels identified in the study, seven (36.8%) belonged to the domain 4: activity/rest and five labels (26.3%) belonged to the domain 11: safety/protection. The domains: Elimination and Exchange; Perception/Cognition; Health promotion; and Comfort presented respectively: three (15.7%), two (10.5%) and one (5.2%) diagnostic labels5 .

As shown in table 1 , the most frequent ND were: “impaired bed mobility” (n=11; 11.8%), “deficit in self-care for bath/hygiene” (n=11; 11.8%), “deficit in self-care for feeding” (n=10; 10.6%) and “physical mobility impaired” (n= 10.6%).

The present study has data similar to a research developed in the South of the country, with multiple trauma patients, who also identified among the most frequent ND, the diagnosis of “physical mobility impaired”, “bed mobility impaired” and “deficit in self-care for bath”21 .

The mobility of the patient relates to the degree of independence and generally, in cases of trauma is common to be impaired22 . The high frequency of impaired mobility ND in this study may be explained by the fact that one ND is directly related to the other.

The ND “deficit in self-care for bathing/hygiene” had a frequency of 11.8% (n=11). However, another study conducted with patients in a medical clinic unit identified that this was present in 36% of patients23 . Another study conducted with patients with spinal cord injury revealed that a frequency of 93.3% in this ND24 . The ND “deficit in self-care for feeding” used to be common in patients with lesions in the nervous system and such clinical condition can bring serious implications to the nutritional status of the patient because of the patient's physical and cognitive impairment, which are fundamental to promote proper nutrition25 . Before the findings, we can infer that both diagnoses of mobility impaired and self-care deficit can be caused by neurological impairment of patients with TBI.

The literature21 points out that the ND “acute pain” has a direct relation with “impaired mobility” and “deficit in self-care” due to the functional limitations caused by the pain, although in this study the ND “acute pain” presented low frequency of answer, being mentioned only once (n=1; 1.1%).

As seen in table 2 , of 19 (100%) diagnostic labels assessed, 16 (84.2%) were evaluated as highly accurate; three (15.8%) diagnostic labels had frequency response in the category of moderate accuracy, being: “deficit in self-care for bath/ hygiene”, “deficit in self-care for dress-get ready” and “acute pain”; there was no frequency response in the categories of low accuracy and null accuracy (Table 3 ).

It is important to note that the ND “deficit in self-care for bathing/hygiene” was one of the most frequent ND, although they showed moderate accuracy. Such a finding can be explained because the most frequent diagnoses may predict ND with less degree of accuracy because the familiarity of nurses with more frequent ND can cause less attention of nurses, and induce to under-estimate the patient, or a lack of evaluation records which may generate less accurate ND26 . When the nurse identifies clues which may indicate ND not so common in their daily practice, they look for more elaborate strategies that can guide their decision making which results in more accurate ND26 .

Of the 94 ND documented, most (n=88; 93.6%) was assessed as being highly accurate (table 3). Another study developed in a university hospital in the southeast of Brazil identified that 70.4% of ND listed by nurses were also highly accurate25 . A study developed in the northeastern region of the country identified that only 54.9% (expressed based on the NANDA-I) and 39.5% (expressed based on CIPE) of ND were evaluated as highly accurate27 .

It is quite complex to discuss these results27 . Accepting as satisfactory that 93.6% of ND are highly accurate means also accepting as satisfactory that 6.4% of prescribed therapy is based on ND with low degree of accuracy, i.e. that 6.4% of nursing actions performed do not achieve the expected results. The ideal outcome would be that 100% of ND were highly accurate27 .

NDAS-2 was designed to evaluate the accuracy of ND by means of written data and this scale property may indicate erroneously low diagnostic accuracy26 , since the evaluation of the ND accuracy depends on filling completely the records of nursing clinical evaluation. Therefore, the nurse might have evaluated the patient correctly, but a failure in the clues record that describe the ND evaluated may indicate low accurate ND.

One of the factors that may have contributed to the high accuracy of the ND in this study is the way to register the patient assessment in the electronic health record. With the program used by the institution, when the nurse selects the fields that represent the “clues” of the patient under evaluation, the system itself suggests some ND and, from that, the professional selects manually the ND that best express the clinical manifestations of the patient. The literature highlights28 that the ND established with the support of the electronic system ,showed greater degrees of accuracy.

The most frequent degree of accuracy was 13.5 (n=87; 92.6%) and the average of the accuracy degree per ND was 12.9 with a variation of 2 to 13.5 (Figure 1 ). These results corroborate with the findings in São Paulo26) which identified in a study that the most frequent accuracy degree also was 13.5 (n=2,328; 68.1%) and the average of the accuracy degree for nursing diagnosis was 9.8 with a variation of 0 to 13.5.

We must say that the sample of the study, even though it was all from the evaluated period, can be considered a limitation of this research because we infer that in a larger sample of study it would be possible to identify greater variability of diagnostic accuracy scores. The lack of studies on the subject also hindered the discussion of the findings.

CONCLUSIONS

The study identified that the ND of neurological clinical or surgical patients, in a non critical inpatient unit of a teaching hospital in the countryside of Parana, have predominantly high accuracy. This indicator is essential to assist in the process of implementation of the NCS in the institution studied, as it is evident that the diagnostic reasoning process of the nurses surveyed has been carried out effectively, even they do not carry out the NP to most hospitalized patients.

Further research is needed in other hospital units to enable a more expanded review of accuracy of ND listed by the nurses of the institution.

REFERENCIAS

1. Conselho Federal de Enfermagem. Resolução Cofen nº 358/2009. Sistematização da Assistência de Enfermagem - SAE - nas Instituições de Saúde Brasileiras. [Internet] 15 out 2009 [acesso em 7 jan 2017]. Disponível em: http://novo.portalcofen.gov.br/resoluo-cofen-3582009_4384.html. [ Links ]

2. Malucelli A, Otemaler KR, Bonnet, M, Cubas MR, Garcia TR. Sistema de informação para apoio à sistematização da assistência de enfermagem. Rev. bras. enferm. [Internet] 2010; 63(4):629-36 [acesso em 18 abr 2016]. Disponível: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/reben/v63n4/20.pdf. [ Links ]

3. Jesus ACC. O processo de enfermagem. In: Tannure MC, Pinheiro AM. SAE: Sistematização da assistência de enfermagem: Guia prático. 2.ed. - Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara koogan, 2010. p.17-22. [ Links ]

4. Santos FOF, Montezeli JH, Peres AM. Autonomia profissional e sistematização da assistência de enfermagem: percepção de enfermeiros. Rev. min. enferm. [Internet] 2012; 16(2):251-7. [acesso em 13 abr 2016]. Disponível: http://reme.org.br/content/imagebank/pdf/v16n2a14.pdf [ Links ]

5. Herdeman TH, Kamitsuru S, organizadores. Diagnósticos de enfermagem da NANDA: definições e classificações 2015-2017. Porto Alegre: Artmed; 2015. [ Links ]

6. Pereira JMV, Cavalcanti ACD, Lopes MVO, VG Silva, Souza RO, Gonçalves LC. Accuracy in inference of nursing diagnoses in heart failure patients. Rev. bras. enferm. [Internet] 2015; 68(3): 690-96 [acesso em: 15 abri 2016]. Disponível: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/reben/v68n4/en_0034-7167-reben-68-04-0690.pdf [ Links ]

7. Oliveira ARS, Carvalho EC, Rossi LA. Dos princípios da prática à classificação dos resultados de enfermagem: olhar sobre estratégias da assistência. Ciênc. Cuid. saúde [Internet] 2015; 14 (1): 986-992 [acesso em: 13 abr 2016]. Disponível: http://www.periodicos.uem.br/ojs/index.php/CiencCuidSaude/article/view/22034/14208. [ Links ]

8. Lunney M. Critical Need to Address Accuracy of Nurses' Diagnoses. Journal of Inssues in Nursing. OJIN. [Internet] 2008; 13 (1) [acesso em 11 jun 2016]. Disponível: http://www.nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/ANAMarketplace/ANAPeriodicals/OJIN/TableofContents/vol132008/No1Jan08/ArticlePreviousTopic/AccuracyofNursesDiagnoses.html. [ Links ]

9. Lunney M (cols). Pensamento crítico para o alcance de resultados positivos em saúde: análises e estudos em enfermagem. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 2011. p.45. [ Links ]

10. Matos FGOA, Cruz DALM. Construção de instrumento para avaliar a acurácia diagnóstica. Rev. esc. enferm. USP [Internet] 2009; 43(Esp):1088-97 [acesso em: 18 abr 2016]. Disponível: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/reeusp/v43nspe/a13v43ns.pdf. [ Links ]

11. Silva ERR da, Lucena AF (cols). Diagnósticos de enfermagem com base em sinais e sintomas. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 2011. p. 31. [ Links ]

12. Matos FGOA, Cruz DALM. Escala de acurácia de diagnósticos de enfermagem. In: NANDA International Inc: Herdman TH, organizadores. PRONANDA Programa de Atualização em Diagnósticos de Enfermagem: Ciclo 1. Porto Alegre: Artmes/Panamericana; 2013. p.91-116. [ Links ]

13. Rosin J, Matos FGOA, Alves DCI, Carvalho ARS, Lahm JV. Identificação de diagnósticos e intervenções de enfermagem para pacientes neurológicos internados em hospital de ensino. Ciênc. cuid. saúde [Internet] 2016, v.15,n 4, pp: 607-615. [acesso em 12 fev 2017. Disponível: http://periodicos.uem.br/ojs/index.php/CiencCuidSaude/article/view/31167/pdf. [ Links ]

14. Maria MA, Quadros FAA, Grassi MFO. Sistematização da assistência de enfermagem em serviços de urgência e emergência: viabilidade de implantação. Rev. bras. enferm. [Internet] 2012, vol.65, n.2, pp. 297-303. [acesso em 05 nov 2016]. Disponível: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/reben/v65n2/v65n2a15.pdf [ Links ]

15. Universidade Federal do Paraná. Hospital de Clinicas, Diretoria de Enfermagem - Comissão de Sistematização da Assistência de Enfermagem (COMISAE). Avaliação de enfermagem: anamnese e exame físico (adulto, criança e gestante). Curitiba: Hospital de Clinicas, 2014. [ Links ]

16. Gaudêncio TG, Leão GM. A epidemiologia do traumatismo crânio encefálico: Um Levantamento Bibliográfico no Brasil. Rev. neurocienc. [Internet] 2013; 21(3):427-434. [acesso em 09 jan 2017]. Disponível: http://www.revistaneurociencias.com.br/edicoes/2013/RN2103/revisao/814revisao.pdf [ Links ]

17. Oliveira ARS, Costa AGS, Moreira RP, Cavalcante TF, Araujo TL. Diagnósticos de enfermagem da classe atividade/exercício em pacientes com acidente vascular cerebral. Rev. enferm. UERJ [Internet]. 2012; 20(2): 221-8. [acesso em 21 ago 2016]. Disponível: http://www.scielo.br/ pdf/reeusp/v44n3/29.pdf [ Links ]

18. Oliveira IM, Silva RCG. Comparação do grau de acurácia diagnóstica de graduandos e enfermeiros em programas de residência. Rev. min. enferm. [Internet]. 2016; 20: 952. [acesso em 14 set 2016]. Disponível: http://www.reme.org.br/artigo/detalhes/1085 [ Links ]

19. Aguiar LL; Guedes MVC. Diagnósticos e intervenções de enfermagem do domínio segurança e proteção para pacientes em hemodiálise. Enfermería Global. [Internet]. 2017. 47: 13-25. [acesso em 2 nov 2017]. Disponível em: http://revistas.um.es/eglobal/article/viewFile/248291/212811 [ Links ]

20. Lemos RX, Raposo SO, Coelho EOE. Diagnósticos de enfermagem identificados durante o período puerperal imediato: estudo descritivo. Rev. enferm. Cent. -Oeste. Min. [Internet] 2012; 2(1):19-30 [acesso em 17 ago 2016]. Disponível: http://www.seer.ufsj.edu.br/index.php/recom/article/view/183/252. [ Links ]

21. Bertoncello, KCG; Cavalcanti CDK; Ilha P. Diagnósticos reais e proposta de intervenções de enfermagem para os pacientes vítimas de múltiplos traumas. Rev. eletrônica. enferm. [Internet]. 2013 out/dez;15(4):905-14 [acesso em 14 set 2016]. Disponível: https://www.fen.ufg.br/fen_revista/v15/n4/pdf/v15n4a07.pdf. [ Links ]

22. Silva FS, Fernandes MV, Volpato MP. Diagnósticos de enfermagem em pacientes internados pela clínica ortopédica em unidade médico-cirúrgica. Rev. gaúch. enferm. [Internet]. 2008 29(4):565-72. [acesso em 20 ago 2016]. Disponível: http://seer.ufrgs.br/RevistaGauchadeEnfermagem/article/view/ 3826.). [ Links ]

23. Lima AFC, Fugulin FMT, Castilho V, Nomura FH, Gaidzinski RR. Contribuição da documentação eletrônica de enfermagem para aferição dos custos dos cuidados de higiene corporal. J. Health Inform. [Internet]. 2012. Disponível: http://www.jhi-sbis.saude.ws/ojs-jhi/index.php/jhi-sbis/article/view/239/129. [ Links ]

24. Brito MAGM, Bachion MM, Souza JT. Diagnósticos de enfermagem de maior ocorrência em pessoas com lesão medular no contexto do atendimento ambulatorial mediante abordagem baseada no modelo de Orem. Rev. eletrônica. enferm. [Internet]. 2008; 10(1):13-28 [acesso em 18 nov 2016]. Disponível: http://www.fen.ufg.br/revista/v10/n1/v10n1a02.htm [ Links ]

25. Simony RF, Chaud DMA, Abreu ES de, Assis SMB. Caracterização do estado nutricional dos pacientes neurológicos com mobilidade reduzida. Journal of Human Growth and Development. [Internet] 2014; 24(1): 42-48 [acesso em 23 set 2016]. Disponível: http://www.jhi-sbis.saude.ws/ojs-jhi/index.php/jhi-sbis/article/view/239/129. [ Links ]

26. Matos, FGOA. Fatores preditores da acurácia dos diagnósticos de enfermagem. [tese]. São Paulo: Escola de Enfermagem da Universidade de São Paulo. 2010. [ Links ]

27. Morais SCRV, Nobrega MML, Carvalho EC. Convergence, divergence and diagnostic accuracy in the light of two nursing terminologies. Rev. bras. enferm. [Internet] 2015; 68(6):777-83 [acesso em 26 out 2016]. Disponível: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/reben/v68n6/en_0034-7167-reben-68-06-1086.pdf [ Links ]

28. Peres HHC, Jensen R, Martins TYC. Avaliação da acurácia diagnóstica em enfermagem: papel versus sistema de apoio à decisão. Acta paul. enferm. [Internet]. 2016, vol.29, n.2, pp.218-224. [acesso em 10 dez 2016]. Disponível: http://www.redalyc.org/pdf/3070/307046625013.pdf [ Links ]

Received: June 02, 2017; Accepted: November 09, 2017

texto en

texto en