Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Enfermería Global

versión On-line ISSN 1695-6141

Enferm. glob. vol.18 no.54 Murcia abr. 2019 Epub 14-Oct-2019

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/eglobal.18.2.344761

Originals

Perceived quality of care and satisfaction for deaf people with regard to primary care in a Health Area in the region of Murcia

1PhD in Nursing. University College of Nursing of Cartagena. University of Murcia. Spain

Objective:

To describe the quality of care and satisfaction with regard to the primary care services of the Health Area II Cartagena of the Murcia Health Service as perceived by deaf people of Cartagena and the region.

Method:

Observational, descriptive and cross-sectional study. The data were collected through the simultaneous translation of the Questionnaire on Evaluation and Improvement of the Quality of Care (EMCA) relative to the Perceived Quality in Primary Care. The variables analyzed were: age, sex, level of education, kind of deafness, first language and use, communication systems or supports, quality of perceived service, perception of professionalism and humane treatment by doctors, nurses and administrative personnel and overall satisfaction perceived regarding their Health Center.

Results:

Professionalism and humane treatment on behalf of doctors and administrative staff was perceived as deficient, yet this perception was good in the case of nurses. Overall satisfaction is lower than that in the general population. There are statistically significant differences between the type of deafness and the perceived professionalism, the humane treatment and the perceived professionalism and between the communication system or support and the perceived quality of care.

Conclusions

The health care provided to this group with special needs must be adapted so that they perceive quality health care leading to increased access and monitoring of deaf people in the health system.

Key words: quality of care; patient satisfaction; primary care; deafness; hearing impairment

INTRODUCTION

As established by the World Health Organization (WHO), hearing impairment or disability implies difficulty in perceiving the dimensions of sound and significantly affects the lives of people affected, making the use of special resources necessary1.

With regard to the health care received by people with hearing impairment, various international studies have reported that there is a higher prevalence of under treatment in this population, as well as poorer control of risk factors in cardiovascular diseases, joint diseases and self-perceived depression compared to individuals with visual and cognitive disabilities2and to the general population3. Likewise, it has been found that the deaf community makes less use of Primary Care services and more use of hospital services4, they resort to a greater extent to private health services or even forgo health care due to their complicated relationship with health professionals5 6, which is due to the difficulties in the communication process, the sheer necessity of another person to mediate and the perception of bitterness and tension on the part of health personnel5 7.

This complicated relationship with health professionals makes it difficult for people with hearing impairment to access health care8, prevention and treatment9.

Deaf people also report several intrinsic barriers in the health system and the unavailability of qualified personnel to respond to their needs10, which makes them afraid of being misinterpreted, fear of medication errors and being deceived5 7.

The Council of Europe Action Plan 2006-2015 for the Promotion of Rights and Full Participation of People with Disabilities (PWD) in society insists that “people with disabilities, like other members of society, need health care and should be able to access, on an equal footing, quality health services that integrate environmentally friendly practices with the rights of customers”11. This principle is supported by WHO, which establishes as a fundamental right of every human being the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health, including access to timely, accepTable and quality health care12.

Providing good quality care consists in carrying out the necessary actions in each process at the lowest possible cost and in such a way that those assisted are satisfied. The quality of care requires suitability of clinical practice, its excellence and the satisfaction of those who receive it. Achieving these three attributes in healthcare means achieving scientific-technical quality and relational quality, which is measured by the system's ability to communicate with those who receive the services and is based on observance, among other, of the principles of healthcare ethics and of the values and preferences of those who receive care13.

In this context, and specifically related to the Deaf community, theEdinburgh & Lothian Deaf HealthandDeaflink Newcastleprojects in the United Kingdom are clear examples of community strategies implemented in Europe aimed at advocating, training and mediating in the right of deaf people to the highest attainable standard of health without discrimination on the grounds of disability, recognizing the particular characteristics and linguistic and cultural identity of the deaf population11.

Spain, however, has not yet established an efficient and widespread development of national strategies specifically targeting the deaf community, whereby this group is exposed in terms of due fulfillment of their fundamental rights, despite the existence of specific legislation in this regard (Article 10. b. of current Act 27/2007, of 23 October)11 14. Although pilot video-interpretation projects in sign language have been implemented in hospitals of some autonomous communities (Navarra, Madrid)15, there is a lack of studies and measures in other regions.

Hearing disability affects 402,615 people in Spain, 61.5% of whom have been officially recognized this disability. Among these, 51.5% report difficulties in communicating and 33.9% difficulties in relating to others16. Specifically, in the region of Murcia, the regional Statistical Center reported an increase in the number of people with recognized hearing disability from 2009 (3,000 people) to 2014 (4,200 people)17. It is estimated that there are 36,500 people with disabilities in Cartagena. Hearing disability represents the first disability in 9.5%18

It is important to note that the Deaf community is a large and heterogeneous group, which, in an inherent way, entails various adaptive implications that vary both depending on the time of onset of deafness (namely, before language development or pre-lingual, or post-lingual), and on the greater or lesser degree of residual hearing (mild or profound hypoacusia), or its total absence (cophosis or total deafness)11. This heterogeneity can trigger different treatment needs and can determine the perception of the quality of care received.

Taking into account the scarce number of studies on health satisfaction in this community in Spain and in the Murcia Region, the diversity among the deaf community and the need to measure the satisfaction of the disabled as a global indicator key to measuring the effectiveness of the health and social care area,19we aim to describe the perceived quality of care, the professionalism and the humane treatment on behalf of doctors, nurses and administrative staff, and customer satisfaction relative to Primary Care services of the Health Area II Cartagena in the Murcia Health Service, as perceived by deaf people in Cartagena and the region.

METHODOLOGY

Observational, descriptive and cross-sectional study. The study population includes 24 deaf individuals over 18 years of age members and/or users of the Association of Deaf People of Cartagena and region (Asociación de Personas Sordas de Cartagena - ASORCAR) and the Association of Parents of Children with Hearing Impairments (Asociación de Padres de Niños con Deficiencias Auditivas - APANDA), making up 20% of the study population.

For the recruitment of the population, we contacted the directors of APANDA and ASORCAR, the Spanish sign Language Interpreters (ILSE) of reference of each of the associations and the nurses of the Otolaryngologic Nursing Ward of the Hospital General Universitario Santa Lucía, requesting a meeting to make a formal presentation of the project and to seek the collaboration of those involved by enabling contact with their members, non-user members and non-member users.

The measurement instrument used was theQuestionnaire on Evaluation and Improvement of the Quality of Care (EMCA) relative to the perceived quality in Primary Care20, specifically the items “overall assessment of care” (five questions) and “sociodemographic data” (four questions). The questionnaire has been developed by the Ministry of Health and Consumption of the region of Murcia; it is structured as report-type questions, inquiring about the occurrence or not of the circumstances and objective data that influence the levels of perceived quality and patient satisfaction. The questionnaire has undergone a metric validation analysis, confirming that it is a valid and reliable tool capable of discriminating and identifying the most relevant dimensions of quality.

The study variables are: age, sex, level of education, type of deafness (pre-or post-lingual), first language and use, communication systems or supports, perceived quality of care, perceived professionalism of doctors, nurses and administrative staff, humane treatment by doctors, nurses and administrative staff and overall satisfaction perceived relative to their health center or office.

Prior to collecting information, each questionnaire was subject to a pilot trial in both associations being read with the assistance of the Spanish sign Language Interpreters (ILSE) and a heterogeneous group of six deaf people, invited by each association, in order to resolve the potential doubts that might occur during the development of the simultaneous interpretation whereby the information would be collected. Following the completion of the pilot trial, three serial meetings were held with various professionals familiar with the approach to the Deaf community (ILSE, Speech Therapist and Social worker) in order to determine the relevant corrections to promote the understanding and handling of the questionnaires.

The questionnaires were completed between June 30 and September 1 2016 through the simultaneous interpretation system. The researchers remained outside the room during the completion of the documents in order to create an environment of privacy and confidentiality.

The SPSS 21.0 statistical package for Windows was used for data analysis

This study ensured the confidentiality, anonymity and autonomy of the participating subjects. The participants expressly authorized the interview by signing the informed consent document. Likewise, the teams of professionals and/or the relevant directors from ASORCAR and APANDA were asked to approve the project, to collaborate and to explain the project to the participants using sign language. The anonymity of the participants was ensured by coding each interview.

RESULTS

Profile of participants

The participants included 41.7% men and 58.3% women. The average age of participants was 43 years old (+/-15).

With regard to the level of education, 58.3% had no education or only primary education, 16.67% had completed vocational training and only 4.17 % had a university degree

A total of 83.3% of participants had pre-lingual deafness

70.8% of participants considered Spanish sign language as their first language, not mastering oral language, while only 4.2% considered spoken language their first language. In addition, 41.7% reported not to master fluent written Spanish, nor did they consider lip-face reading as a useful ability to communicate in health services.

Quality of care and satisfaction in terms of the health care received

Quality of care, humane treatment, perceived professionalism and overall satisfaction were assessed.

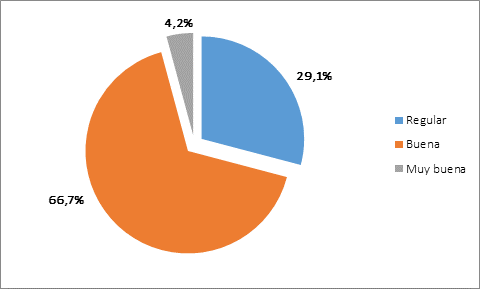

With regard to the quality of care received, 66.7% of respondents rated the quality of care at their health center as “good”, while 29.1% defined it as "average" (Figure 1).

When analyzing statistical relationships between dependent and independent variables, statistically significant differences (p<0.03) have been found between the communicative system or support and the perceived quality of care, so deaf people not using any communicative system or support have a poorer perception of the quality of care received.

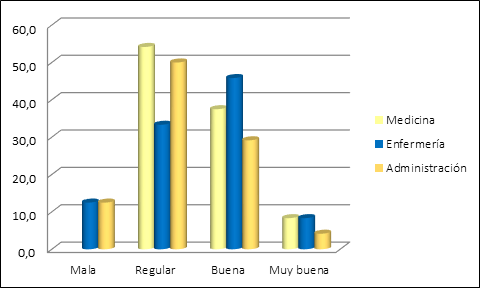

In relation to the perceived professionalism of the staff, most participants rated it as “average” overall for the professionals of their Health Center.

When distinguishing between professional categories, most participants rated the professionalism of doctors as “average” (54.2%), with the same rating for the administrative staff (52.2%), while most perceived the professionalism of the nursing staff as good (48.5%) or very good (8.3%) (Figure 2).

There are statistically significant differences between the type of deafness and the perceived professionalism of doctors (p<0.05) and administrative staff (p<0.03), not so with nursing staff, while participants with pre-lingual deafness had the worst perception of professionalism in doctors and administrative staff.

Similarly, statistically significant differences have been found between the communicative system or support and perceived professionalism (p<0.0005), whereby deaf people who do not use any communicative system or support have a poorer perception of the professionalism of staff at their health center.

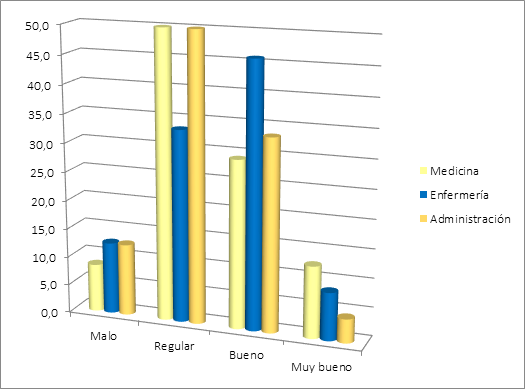

With regard to the perceived humane treatment, 50% rated the treatment received by doctors as ”average”, 45.8% rated the treatment received by nurses as “good” and 50% rated the treatment received by administrative staff as “average”, so the perception of treatment rated as “average” for Health Center professionals was predominant (Figure 3).

There are statistically significant differences between the communicative system or support and the perception of humane treatment (p<0.02) with regard to doctors. It is established that deaf people not using any communicative system or support have a poorer perception of the humane treatment by doctors.

Global satisfaction with their health center or office includes care received, cleanliness, accessibility and ease of appointment. In general, participants were satisfied, with a score of 6.95 out of 10 points.

DISCUSSION

Comparing the results obtained with those of the study carried out by the Murcia Health Service (2014) on the general population21, the general population satisfaction averaged 7.9 points out of 10, while our study average was one point lower

Customer satisfaction with regard to the care received is closely linked to the perceived professionalism and the humane treatment from professionals who at any point are involved in the care process, both items have been rated in our study and in that conducted by the Murcia Health Service on the general population21. Doctors were rated by 94% as “good” or “very good” in terms of professionalism, while in the case of deaf people in our study this rating was given by 45.8% of the respondents. On the other hand, professionalism and humane treatment on behalf of nurses were rated as “Good” and “Very good” by 91.2% and 91.7% of the respondents for the Murcia Health Service respectively, whereas in our study, only 54.1% of surveyed individuals gave similar answers.

Various studies22 23have reported that the nursing staff attempts to bond with patients who are deaf and with hearing impairment in order to address their needs and understand them, which might explain the higher rating in terms of humane treatment and professionalism for the Nursing staff as compared to other professionals. In fact, Loredo Martinez and Matus Miranda23, in their review paper, conclude that by establishing direct face-to-face contact between the nurse and the person with a hearing impairment, this creates bonds of trust, making understanding easier for the person with hearing impairments.

Although the perceived humane treatment and professionalism with respect to nurses is lower in the Deaf community than in the general population, this is due to the nurse's difficulty in the communication process which affects the care they provide; nurses reported in the study by Gomes et al.22that in their academic and professional life they had not received specific training on how to care for and communicate with deaf patients.

Deaf and hearing impaired people live in a society made up mostly normally hearing people, so for their integration they must overcome existing communication barriers that are apparently invisible to the eyes of people without hearing disabilities.

On the other hand, the fact that people with pre-lingual deafness have a poorer perception of the quality, professionalism and treatment may be related to the fact that they have to continually face the structural and communicative barriers and prejudices of people and the system, which ultimately do not solve their problems

Various studies have highlighted the difficulty posed to deaf people when accessing services8 9, sometimes ignoring their need to be monitored by the nursing staff and doctors in chronic processes, which negatively affects their health.

The results of our study should be interpreted considering the limitations inherent in the study methodology and the small sample size.

CONCLUSIONS

The Deaf People of Cartagena studied have a lower perceived quality of care and a lower overall satisfaction compared to the general population, in all the assessed items.

Nurses are more highly rated than doctors and administrative staff in terms of professionalism and humane treatment.

The health care provided to this group with special needs must be adapted so that they perceive quality health care leading to increased access and monitoring of deaf people in the health system.

Making visible the situation of the Deaf community with regard to the use, accessibility and perceived satisfaction in Primary Care Services is necessary and is the basis for generating specific responses to the potential needs and deficiencies of the Deaf community, proposing effective communication tools, optimizing the use of available health services, improving the control of chronic conditions and increasing prophylactic interventions in this community.

REFERENCIAS

1. Delgado Sánchez P. Estudio sobre la Actitud de los Empleadores hacia la Inclusión de Personas Sordas al Campo Laboral. Monterrey: Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León. Facultad de Psicología; 2012. [ Links ]

2. Horner-Johnson W, Dobbertin K, Lee JC, Andresen EM. Disparities in chronic conditions and health status by type of disability. DisabilHealth J. 2013;6(4):280-6. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24060250 [ Links ]

3. Emond A, Ridd M, Sutherland H, Allsop L, Alexander A, Kyle J. The current health of the signing Deaf community in the UK compared with the general population: a cross-selectional study. BMJ Open. 2015;5(1). Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25619200 [ Links ]

4. Buchrieser Freire D, Petrucci Gigante L, Umberto Beria J, Santos Palazzo L, Leal Figueuredo AC, Raymann BCW. Acesso de pessoas deficientes auditivas a serviços de saúde em cidade do Sul do Brasil. Cad Saúde Pública. 2009;25(4). Available from: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0102311X2009000400020 [ Links ]

5. Da Silva Bentes IM, Figueirêdo Vidal EC RME. Deaf person's perception on health care in a midsize city: an descriptive-exploratory study. OBJN. 2011;10(1). Available from: http://www.objnursing.uff.br/index.php/nursing/article/view/j.16764285.2011.3210.2/j.1676-4285.2011.3210.1 [ Links ]

6. Emond A, Ridd M, Sutherland H, Allsop L, Alexander A KJ. Access to primary care affects the health of Deaf people. Br J Gen Pr. 2015;65(31). Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25624302 [ Links ]

7. Polanco Teijo F, García-Ruise, S. Necesidad sentida de las mujeres sordas durante el parto y el puerperio inmediato en el ámbito hospitalario. Cult los Cuid. 2010;14(28). Available from: http://culturacuidados.ua.es/enfermeria/article/view/369 [ Links ]

8. Da Silva Aragão J, De Oliveira Magalhães IM, Silva Coura A, Rodrigues Silva AF, Pereira Cruz GK. Access and communication of deaf adults: a voice silenced in health services. J res fundam Care. 2014;6(1):1-7. [ Links ]

9. Kuenburg A, Fellinger P, Fellinger J. Health Care Access Among Deaf People. 2018:1-10. [ Links ]

10. Moreira da Costa LS, Nascimento de Almeida RC, Cristina Mayworn M, Figueiredo Alves PT, Martins de Bulhões PA, Miro Pinheiro V. O atendimento em saúde através do olhar da pessoa surda: avaliação e propostas. Rev Bras Clin Med. 2009;7:166-70. [ Links ]

11. Muñoz Baell IM, Ruiz Cantero MT, Álvarez Dardet C, Ferreiro Lago E Aroca Fernández, E. Comunidades sordas ¿pacientes o ciudadanas? Gac Sanit. 2011;25(1). Available from: http://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S021391112011000100012 [ Links ]

12. OM de la Salud. Constitución de la Organización Mundial de la Salud. 2006. [ Links ]

13. Rodríguez Pérez MP, Grande Arnesto, M. Calidad asistencial: Concepto, dimensiones y desarrollo operativo. Escuela Nacional de Sanidad, editor. Madrid; 2014. Available from: http://e-spacio.uned.es/fez/eserv/bibliuned:500957/n14-1_Calidad_asistencial.pdf [ Links ]

14. Boletín Oficial del Estado número 255. Ley 27/2007, de 23 de octubre, por la que se reconocen las lenguas de signos españolas y se regulan los medios de apoyo a la comunicación oral de las personas sordas, con discapacidad auditiva y sordociegas. 2017. [ Links ]

15. Commité Español de representantes de personas con discapacidad. Por un espacio socio-sanitario inclusivo- informe CERMIN. Déficits, retos y propuestas de mejora. Colección. Madrid; 2016. [ Links ]

16. Serna López EM. La Lengua de Signos Española en Internet: Análisis y Diagnóstico de la Accesibilidad. Universidad de Murcia. Departamento de Lengua Española y Lingüística General; 2015. [ Links ]

17. Murcia. Centro Regional de Estadística de Murcia. Evolución de las personas con certificado de discapacidad según tipo de discapacidad [Internet]. Available from: http://www.carm.es/econet/sicrem/pu2034/sec6.html [ Links ]

18. Bocos E. Estudio sobre la Discapacidad en Cartagena. Cartagena; C de SSA de, editor. 2014. [ Links ]

19. Comité Español de representantes de personas con Discapacidad. Espacio sociosanitario inclusivo. Documento de posición del CERMI Estatal en materia sociosanitaria. 2014. 1-86 p. [ Links ]

20. Servicio murciano de Salud. Información sobre la asistencia recibida en su centro de salud o consultorio. :1-16. [ Links ]

21. Servicio Murciano de Salud C de S y PS. Calidad percibida por los usuarios de los Centros de Atención Primaria del Servicio Murciano de Salud. [Internet]. 2014. Available from: https://sms.carm.es/somosmas/documents/63024/0/Calidad+Percibida+en+AP+2014.pdf/1945ab5a-d28b-4df8-9cb3-4931c9883953 [ Links ]

22. Gomes V, Correa Soares M, Marfrin Muniz R, De Sosa Silva J. Vivencia del enfermero al cuidar sordos 7/o portadores de deficiencia auditiva. Enfermería Glob. 2009;(17):1-10. [ Links ]

23. Loredo Martínez, N. & Matus Miranda, R. Intervenciones de comunicación exitosas para el cuidado a la salud en personas con deficiencia auditiva. Enferm Univ. 2012;9(4):57-68. Available from: http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1665-70632012000400006 [ Links ]

Received: October 05, 2018; Accepted: December 14, 2018

texto en

texto en