Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Enfermería Global

versión On-line ISSN 1695-6141

Enferm. glob. vol.20 no.62 Murcia abr. 2021 Epub 18-Mayo-2021

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/eglobal.435891

Originals

HIV as a means of materializing Gender Violence and violence in same-sex couples

1Doctor in Social Work. Research Teaching Staff of the Faculty of Social Work of Culiacán. Autonomous University of Sinaloa. Mexico

2Social Worker of the General Hospital of the Zone with Family Medicine No. 6 of the Mexican Institute of Social Security (IMSS) of Nuevo León. Mexico

Objective:

The general objective of this research is to identify the prevalence and characteristics of partner violence (perpetrator and recipient) in HIV positive patients enrolled in the Mexican Institute of Social Security (IMSS, in Spanish) in the state of Nuevo Leon, Mexico.

Methodology:

A quantitative research was proposed, through a descriptive and transversal design, using as main instrument the Likert scale of violence in partner relationships of Cienfuegos and the Likert scale on the use of HIV as a means to materialize violence. We applied 265 self-administered questionnaires and obtained a statistic sample of 198 patients

Results:

There is a prevalence of partner violence of 40.40% as a receiver and of 40.90% as a perpetrator, psychological violence is the most frequent form in both cases. The prevalence of the use of HIV as a means of materializing partner violence as a recipient is of 4.54% and of 2.52% as a perpetrator. There is a higher proportion of non-heterosexual female victims and aggressors, and of couples in which both members are HIV positive; as well as in patients with a higher level of secure attachment and satisfaction with life.

Conclusions:

As in GBV (gender-based violence), there is evidence of the existence of violence in same-sex relationships in which one of the members is HIV positive. Likewise, it is possible to corroborate that HIV is used as a means to exercise partner violence.

Key words: partner violence; intra-gender violence; HIV

INTRODUCTION

The scientific literature on gender-based violence (GBV) shows that women who are carriers of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) have a high incidence, with half of the women being victims of violence by their partners1; different studies place this incidence higher than the one of couples in which none of the members is seropositive2.

The social stigma attached to the virus contributes to the subjugation that patriarchal cultures reproduce around women (3,4; this is produced through processes in which the lack of recognition is materialized through different forms of contempt. In this sense, in the affective sphere, recognition (love) and the principle of the attention of needs is achieved through self-confidence and makes use of abuse as a means of contempt 5.

Alonso, Cerezo, Pagés, Ramos, and Torricelli point out that there are social determinants of HIV and GBV which function as determinant factors, among which these authors mention: (1) the social perception of violence, insecurity and impunity, (2) limited access to education and work, (3) restricted access to comprehensive and differentiated care in the health services, (4) macho social behaviors and patriarchy, (5) discrimination against people because of their sexual orientation, and (6) stigmatization and discrimination against women with HIV 6. Likewise, regarding the specific forms in which HIV is used as a means of materializing GBV (in addition to physical, psychological, economic and sexual violence), different authors describe actions such as (1) preventing access to antiretroviral treatment, (2) prohibiting access to consultations, (3) discouraging medication/treatment, and (4) destroying antiretroviral medication 2,7. This set of factors trigger a negative social impact and consequences for the physical and psychosocial health of women, including the decrease of CD4+ lymphocytes 8.

One of the variables used to analyze partner relationships is attachment, which refers to a self-schema model that regulates relationships with others, based on patterns of social interaction related to affective ties 9; there are four main types of attachment10: (1 secure attachment (high personal value, feeling comforTable with intimacy and autonomy), (2) concerned attachment (low personal value and positive evaluation of others), (3) fearful attachment (low personal value, fear of intimacy and social avoidance) and (4) avoidant attachment (high personal value, rejection of intimacy and dependence).

Taking into consideration the Latin American context, the studies on GBV and HIV are rather scarce; in Colombia, the quantitative study of Arevalo-Mora 8 identified that out of 223 HIV positive women, 33.6% suffered from partner violence. Another study by the same author, based on a qualitative methodology, warns that this type of situations has the consequences of a low self-esteem in women, a damage in their self-image, high rates of depression and feelings of guilt 11. On the other hand, in Brazil, one study indicates that victims have difficulty recognizing acts of sexual violence 12, while another study shows that living in situations of GBV influences adherence to treatment13; likewise, in a study conducted in São Paulo with a sample of 2,780 women, 59.8% suffered from GBV 14, while another study indicates that in a sample of 57 Brazilian women of color who are HIV-positive, 28% suffered from GBV 15. In Argentina, a qualitative study analyzes the life stories of HIV-positive women who are victims of GBV and the public policies in this regard 16; another qualitative study indicates that racial and gender oppression are factors that favor GBV 17. Moreover, in Chile, a study with a sample of 100 HIV-positive women showed that 77% suffered from GBV; and psychological violence was the most frequent form 18. Finally, in Mexico, a study with an indigenous population confirmed the existence of this type of violence and indicated that the trajectory of the disease exacerbates the forms of violence 19. Another qualitative study indicates that migrant women have difficulty recognizing acts of sexual violence in their daily lives 18.

In all these studies, GBV is analyzed from the perspective of the victims. Likewise, the quantitative studies allude to the forms of generalized violence (physical, psychological, economic and sexual) and do not include specific issues in which HIV is used as a form of materialization of violence. On the other hand, it should be noted that most studies on partner violence and HIV also exclude situations of intra-gender violence (IV); that is, violence that occurs within same-sex couples (gays, lesbians and bisexuals) or in couples where one of the members is transgender, transexual or intersexual 20. In this sense, accounts of intra-gender violence (IV) such as those of Saldivia, Faúndez, Sotomayor and Cea 21 and Rodríguez, Rodríguez-Castro, Lameiras and Carrera 20, show that in this type of relationship produce situations in which HIV is used as a means to materialize violence; either through outing, control, contagion or intimidation.

OBJECTIVES

General

To identify the prevalence and characteristics of partner violence (perpetrator and recipient) in seropositive patients enrolled in the Mexican Institute of Social Security (IMSS, in Spanish) in the state of Nuevo Leon, Mexico.

Specific

To build and validate a scale to measure the use of HIV as a form of partner violence (perpetrator and recipient).

Analyze the prevalence of physical, psychological, economic, sexual and HIV-related violence in HIV-positive patients who are victims and perpetrators of GBV and IV.

To identify the relationship between partner violence, the type of attachment and the level of satisfaction with life of HIV patients. As well as to compare the results according to sex, sexual orientation and seroprevalence of the partners.

METHODOLOGY AND MATERIALS

A descriptive, transversal and analytical study was carried out between December 2019 and February 2020 in the state of Nuevo León, Mexico.

Participants

The department of infectious diseases of the northern area of the IMSS, has a census of 850 HIV-positive patients receiving antiretroviral treatment (universe). A simple random probability sampling with a margin of error of 5% and 95% confidence level was used to select a sample of 265 patients. Once the 265 questionnaires were applied, a selection process was carried out to include those that were complete, obtaining a final sample of 198 patients.

Tools

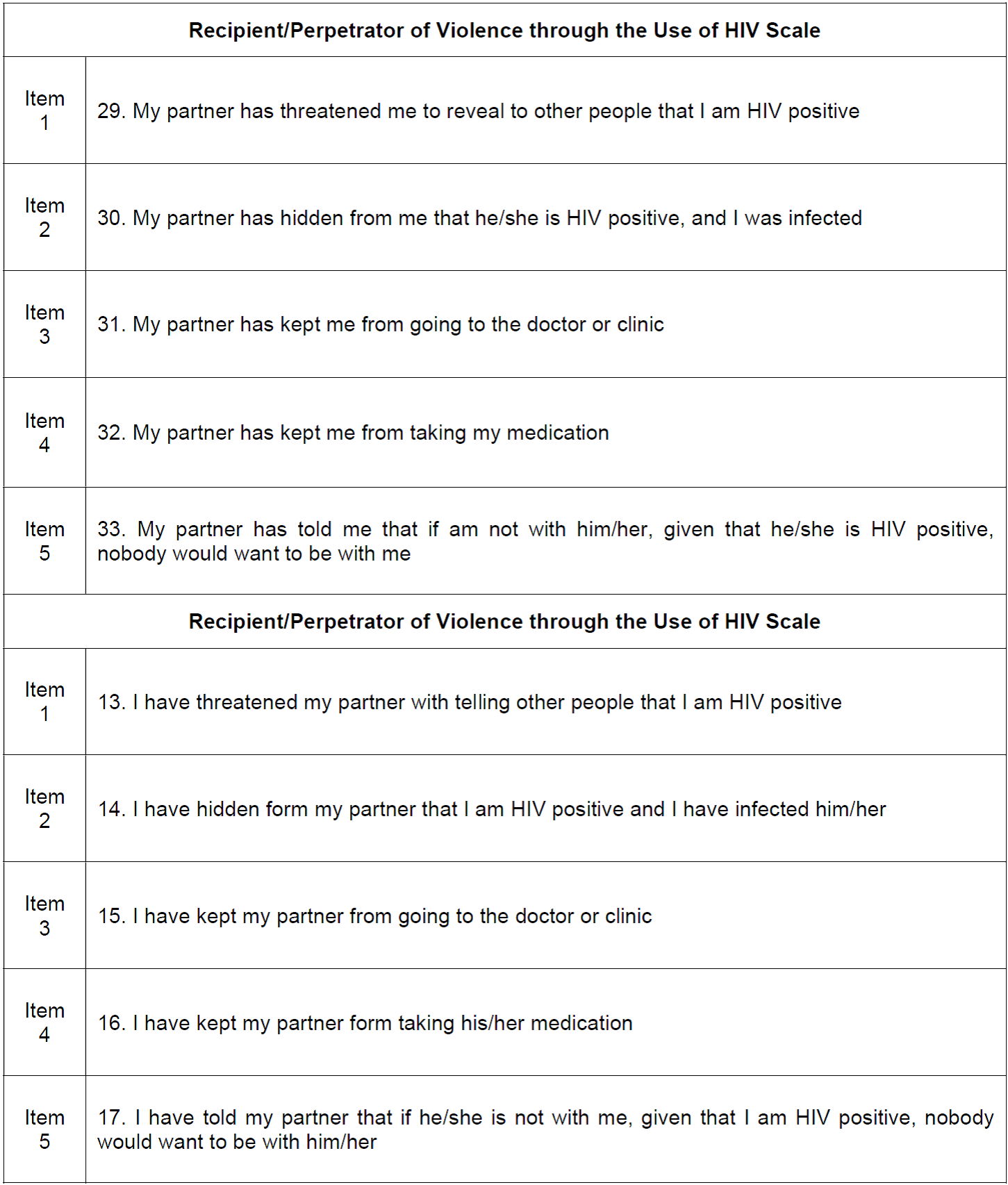

For data collection, a self-administered anonymous questionnaire was applied, which included questions related to the socio-demographic information of the sample, as well as (a) Padilla and Díaz-Loving’s Likert scale of attachment type (secure, concerned, fearful, and avoidant) with 18 questions and values from 1 to 5 10, (b) Pons, Atienza, Balaguer, and García-Merita’s Likert scale of satisfaction with life 22, with up of 5 questions and values from 1 to 5, (c) the Likert scale of violence in partner relationships (perpetrator and recipient) elaborated by Cienfuegos 23, with 12 and 28 items respectively with values from 1 to 5 and, (d) the Likert scale of the use of HIV as a means of materializing violence (perpetrator and recipient) with values from 1 to 5 (see Appendix I).

Procedure

The data collection was carried out in the vicinity of the hospital, so in each consultation the social worker assigned to the department presented our research to each patient and requested their participation on a voluntary basis. Once the questionnaires were collected, they were reviewed and those that were complete were included and codified in a database using SPSS software, for subsequent analysis.

Data analysis

First, the Likert scale of the use of HIV as a means of materializing violence (perpetrator and recipient) was validated. To do this, the analysis proposed by Zamalloa 24 was carried out; it consists of calculating the indicator of homogeneity (>0.20) of the items and analyzing its reliability by applying the methods of separation of halves and of covariance of the items (Cronbach's alpha). Next, a comparison of the statistical means and the t-student test for independent samples was made, with a 95% confidence interval percentage of the scales based on the variables of analysis (seropositive partner and sexual orientation). In addition, cross Tables and chi-square test for each of the forms of violence were carried out. A Pearson correlation analysis was also performed at the level of 0.01 and 0.05 between the scales.

Data treatment

For the realization of the study, the norm 2000-001-009 25 which establishes the dispositions for health research in the Mexican Institute of Social Security (IMSS, in Spanish) was applied; as well as Mexico’s General Law of Health on its chapter on Health Research (Ley General de Salud en Materia de Investigación para la Salud), which is based on the Declaration of Helsinki. Thus, the questionnaires were applied on a voluntary basis, after the explanation of our object of study and after offering a guarantee of anonymity.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the sample

The main socio-demographic characteristics of the population under study are presented in Table 1. As can be seen, the resulting final sample consists of 198 patients between the ages of 20 and 70 (mean=38.45 years), most of whom are men (86.4), Mexicans (99.0%), from the state of Nuevo León (67.2%), from an urban context (80.8%), single (72.7%), without children (81.8%), homosexuals (64.6%), with secondary education (47.0%), employed (87.9%), with a declared medium socioeconomic level (83.3%), non-drug users (94.4%), and whose main way of contracting HIV was sexual intercourse (75.3%); likewise, they are non-participants of HIV positive support groups (93.4%), have never abandoned treatment (78.3%) and have not had any difficulties in accessing treatment (66.7%).

Validation of the Likert Scale on the use of HIV as a means of materializing violence (perpetrator and recipient)

The item-test analysis presented in Table 2, shows that for the homogeneity indicator on the Perpetrator Scale and the Recipient/Perpetrator of Partner Violence through the Use of HIV Scales, all items have a lower level of significance than allowed (<0.05). However, it should be noted that item 3 on the Scale of HIV Use as a Means of Materializing Violence as a Recipient (i.e. My partner has prevented me from going to the doctor or clinic), as well as item 4 on the Scale of Perpetrator (i.e. I have prevented my partner from taking medication), cannot be calculated because at least one variable is constant.

Also, as can be seen in Table 2, between the different dimensions of the Partner Violence Recipient Scale there are significant bilateral Pearson correlations at the level of 0.01 and a significance of less than 0.05 with the HIV Recipient Scale; as well as between the dimensions of the Partner Violence Perpetrator Scale and the HIV Perpetrator Scale.

On the other hand, in terms of reliability, the results of the method of separation of halves and covariance of items (Cronbach's Alpha), as shown in Table 2, reveal the existence of an accepTable level of reliability and internal consistency. For this reason, it is considered appropriate to include the five items from the Perpetrator and Recipient of Partner Violence through the Use of HIV Scales (see Appendix I) in the Cienfuegos’ scales 23.

Table 2. Item-test correlations, Correlations between Scales and Dimensions, Reliability tests and Internal Consistency of both Scales.

Note: **Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (bilateral); .(a) cannot be calculated because at least one variable is constant.

Analysis of the scale of violence in the partner relationship (perpetrator and recipient) and the scale of the use of HIV as a means of materializing violence

The results obtained through the application of the Recipient of Violence Scale show that 80 participants (40.40%) manifest to have experienced situations of violence from their partner. Results also show that 75 patients report having been victims of psychological violence (37.87%), 41 of sexual violence (20.70%), 24 of physical violence (12.12%), 22 of economic violence (11.11%) and 9 of violence through the use of HIV (4.54%). In this sense, as can be seen in Appendix II, the most frequently referred expressions of violence are Item 6 (i.e. My partner watches everything I do) with 48 participants (24.21%), Item 8 (i.e. My partner does not take into account my sexual needs) and Item 22 (i.e. My partner gets jealous and suspicious of my friends) with 38 patients respectively, as well as Item 3 (i.e. My partner gets angry with me if I do not do what he wants) with 35 (17.7%). Likewise, it should be noted that after performing the chi-square test the result of the asymptotic significance for all items registered a value higher than 0.05. With regard to the issues related to the use of HIV as a means of materializing violence, it should be noted that the most reported form is Item 2 (i.e. My partner has hidden from me that he had HIV and has infected me); which was referred to by 2.5% of the sample.

On the other hand, in terms of the Scale of the Perpetrator of the Violence, 81 participants (40.90%) stated that they had used violence against their partner; of which 78 admitted having exercised psychological violence (39.39%), 31 sexual violence (15.65%), 15 economic violence (7.57%), 9 physical violence (4.54%) and 5 violence through the use of HIV (2.52%). In this sense, as shown in Appendix II, the most frequently referred to expressions of violence are Item 3 (i.e. I have become angry when she contradicts or disagrees with me) with 68 participants (34.30%), Item 2 (I have come to yell at my partner) with 62 patients (31.30%) and Item 4 (I have come to insult my partner) with 34 (17.20%). Likewise, it should be noted that after performing the chi-square test, the result of the asymptotic significance for all items registered a value higher than 0.05. Regarding the issues related to the use of HIV as a means of materializing violence, it should be noted that the most reported form is Item 1 (i.e. I have threatened my partner to tell others that I have HIV); which is referred to by 1.0% of the sample.

In Addition, the frequency of the forms of materialization of violence stated by 81 perpetrators corresponds to average values (mean=2.750; SD=1.109), which are higher with respect to sexual violence and violence involving HIV. Regarding the 80 victims the frequency is slightly less, although there are also average values (mean=2.693; SD=0.660), and higher values for sexual and psychological violence (see Table 3).

Analysis according to the variables of sex, sexual orientation and seropositivity status of the partners

Taking into consideration the variables related to sex, sexual orientation and seropositivity status of the partners, the following peculiarities were identified:

With respect to the variable related to sex, 70 men (30.03%) and 10 women (66.66%) stated that they have been victims of their partner, of which 6 men (3.05%) and 3 women (18.51%) suffered violence through the use of HIV. As for the sample that indicates that one partner exercised violence against other partner(s), 69 men (40.35%) and 12 women (44.44%) were identified, of which 3 men (1.75%) and 2 women (7.70%) stated that they have used HIV as a means to exercise violence. On the other hand, the frequency of violence in male recipients (mean=2.63) is occasional and in women (mean=1.90) sporadic, as well as each of its forms of materialization; with the exception of economic violence, which is higher among women. The scale of violence perpetrator is more frequent among men (mean=2.68) than among women (mean=1.96), as well as each of its forms. Likewise, it is important to note that after the t-student test, the bilateral significance of each of the dimensions is greater than 0.05 (see Table 3).

On the other hand, taking into consideration the seropositive status of the partners, it was observed that 32 participants with a seropositive partner (66.66%) and 43 with a serodiscordant partner (50.58%) declared that they have been victims of violence from their partner; of which 6 serodiscordant (6.25%) and 3 seropositive (5.88%) suffered violence through the use of HIV. As for the sample that shows violence towards their partners, 33 participants were identified as having a seropositive partner (68.75%) and 41 as having a serodiscordant partner (48.23%), of which 2 seropositive (4.16%) and 3 serodiscordant (3.52%) admitted that they had used HIV as a means of violence. On the other hand, the frequency of Violence Recipient among serodiscordant couples (mean=2.64) is occasional, as well as in seroprevalent couples (mean=2.37), although slightly higher in the former; as well as each of its forms of materialization. Regarding the Violence Perpetrator Scale, a greater frequency is observed among serodiscordant partners (mean=2.32) than in the seroprevalent ones (mean=2.02), as well as each of their forms of materialization. In each case, it is associated with occasional violence. Likewise, it should be noted that after the t-student test, the bilateral significance of each of the dimensions is greater than 0.05 (see Table 3).

Finally, with respect to sexual orientation, 16 heterosexual participants (32.65%) and 64 non-heterosexual participants (49.95%) reported having been victimized by their partners; of which 2 heterosexuals (4.08%) and 7 non-heterosexuals (4.69%) suffered violence through the use of HIV. As for the sample that indicates violence against their partners, 16 heterosexual participants (32.65%) and 65 non-heterosexual participants (43.62%) were identified, of which 2 heterosexuals (4.08%) and 3 non-heterosexuals (2.01%) reported using HIV as a means of violence. On the other hand, the frequency of violence in heterosexual recipients (mean=2.65) is occasional, as well as in non-heterosexuals (mean=2.63) and slightly higher for the heterosexual sample; as well as each of its forms of materialization with the exception of violence through the use of HIV. As for the Violence Perpetrator Scale, there is a greater frequency in non-heterosexuals (mean=2.32) than in heterosexuals (mean=1.98), as well as each of its forms of materialization with the exception of psychological violence. Likewise, it should be noted that after the t-student test, the bilateral significance of each of the dimensions is greater than 0.05 (see Table 3).

Taking into consideration the results obtained for the attachment type and life satisfaction scales, as shown in Table 4, the results show that the sample of medium-high level of life satisfaction (mean=3.54; SD=1.11); superior in men, non-heterosexual patients and participants with a seroprevalent partner. Likewise, it was identified that the type of attachment with the greatest value in the sample is the secure type (mean=2.58; DT=0.931); which is superior in women, non-heterosexual patients and among serodiscordant couples. Finally, it should be noted that the Perpetrator and Recipient Partner Violence Scales (including the items of the use of HIV as a means of materializing violence) are directly proportional to the scale of safe attachment (Pearson's Correlation Receiver=0.014 and Sig.=0.848; Pearson Perpetrator Correlation=0.011; Sig.=0.879) and inversely proportional to the life satisfaction scale (Pearson Receiver Correlation=-0.007 and Sig.=198; Pearson Perpetrator Correlation=0.826; Sig.=198); although there are no Pearson correlations between them at the level 0.01 and 0.05.

DISCUSSION

Through the present investigation it has been verified that, in the context of the region, there is a prevalence of 40.40% of violence in couples in which one of the partners is seropositive. Comparing this result with other researches, it is observed that the prevalence is higher than studies contextualized in Colombia 8 and Brazil 15; and lower than other studies contextualized in Chile 18 and Brazil 14. However, it should be noted that in these studies the sample consisted only of women. It is also observed that psychological violence, as in the research on GBV conducted by Vidal, Carrasco and Pascal in Mexico 18, is the main way of materializing (37.87%); followed by sexual violence (20.70%), physical violence (12.12%), economic violence (11.11%) and violence in which HIV is used as a means to materialize (4.54%). It has also been found that there is a higher proportion of female victims, non-heterosexual and couples in which both members are HIV positive. However, it is noted that there is a greater frequency over time when the victims are men, heterosexuals and in serodiscordant couples.

On the other hand, through the results obtained, a prevalence of partner violence aggressors has been registered among couples in which one of the members is HIV positive (40.90%). It is also observed that psychological violence is the main way of materialization (39.39%), followed by sexual violence (15.65%), economic violence (7.57%), physical violence (4.54%) and violence in which HIV is used as a means to materialize (2.52%). Also, it has been found that there is a higher proportion of female aggressors, non-heterosexual, and in couples in which both members are HIV positive. However, it is noted that there is a greater frequency over time when the aggressors are men, non-heterosexual who form serodiscordant couples. These results cannot be compared with other researches, as no studies have been identified that address the perspective of the perpetrator of violence in these types of couples. However, it should be noted that this prevalence is similar to that described above with respect to victims. This reveals that in several patients there is bidirectional violence; therefore, it would be ideal to take into account in future investigations the case when the Figure of the perpetrator is manifested as a defense to an aggression or form of violence.

It should also be noted that the results show that in couples in which one of the members is seropositive, in addition to the existence of GBV (gender-based violence) as also presented in previous research 1)(2)(11)(12)(13)(16, there is, as warned by the work of Rodríguez, Rodríguez-Castro, Lameiras and Carrera 20 and Saldivia, Faúndez, Sotomayor and Cea 21, IV (intra-gender violence) in same-sex couples. In fact, the results obtained reveal that IV is more frequent in this type of relationship than VG. However, in the interpretation of the results, it would be convenient to take into account that, as indicated by studies carried out in Brazil 12, Argentina 17 and Mexico 18, the victims present difficulty in recognizing the acts of violence (especially sexual violence). Likewise, it should be considered that, as warned by studies undertaken in Argentina, public policies 16, racial and gender oppression represent factors that favor partner violence in this type of relationship 17. On the other hand, it is observed that the prevalence of partner violence is higher (both in perpetrators and recipients) in couples where both members are HIV positive than in serodiscordant couples. This could be justified by the social stigma attached to the virus which, as different authors point out, contributes to the subjugation that patriarchal cultures reproduce around women 3,4; and also, of the identities that differ from the hegemonic model of masculinity.

Finally, it has been proven that there is a higher level of violence, both in the form of perpetration and reception of violence, among patients with a higher level of secure attachment (characterized by a high personal value, comfort with intimacy and a high level of autonomy) and a lower level of life satisfaction 10. This data corroborates those obtained by another research carried out in Colombia 11, which shows that this type of situations has the consequences in women of a low self-esteem, a damage to their self-image, depression and guilt. Nevertheless, it is important to point out that in the results obtained there are no Pearson correlations at the level of 0.01 and 0.05 between the different scales and subscales. It is also important to note that other factors must also be considered in these processes, such as public policies 16, processes of racial discrimination 17, and the stigma associated with HIV/AIDS 3)(4)(5.

CONCLUSIONS

The results obtained by our research show that, of the 198 seropositive patients of the Infectology Department of the General Zone Hospital of the IMSS in the state of Nuevo León (Mexico), 40.40% have suffered violence form their partners and 40.90% have exercised violence againts their partners. It has also been found that psychological violence is the most frequent and that there is a greater prevalence of this type of violence in both forms (perpetrator and perpetrator) among women, non-heterosexual patients (LGB) and in couples where both members are HIV positive. It has also been found that the frequency of these profiles is sporadic.

As for the violence in which HIV is used as a means for its materialization, 4.54% of the sample indicates that they have been recipients of some of the forms of violence analyzed in the validated scale; and 2.52% declared having acted as a perpetrator. It is also noted that this type of violence is more frequent in women, non-heterosexuals and serodiscordant couples. It is important to take into consideration the social determinants that act as enabling factors such as: machismo, patriarchy, discrimination of people because of their sexual orientation and stigmatization and discrimination against people with HIV among others. It is also important to take into account that, as various authors have pointed out, these factors are the triggers of both social negative repercussions and consequences for the physical and psychosocial health of the victims, including the decrease in CD4+ lymphocytes and adherence to treatment.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank the Mexican Institute of Social Security (IMSS, in Spanish) of the state of Nuevo Leon (Mexico), through which our research questionnaire was been distributed to patients.

REFERENCES

1. Kouyoumdjian FG, Findlay N, Schwandt M, Calzavara LM. A systematic review of the relationships between intimate partner violence and HIV/AIDS. PLoS One. 2013;8(11). Disponible en https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24282566/ [ Links ]

2. Arévalo-Mora L. Violencia de pareja en la mujer que vive con VIH. Revista Colombiana de Enfermería. 2018;16(13): 52-63. Disponible en http://www.sidastudi.org/resources/inmagic-img/DD48695.pdf [ Links ]

3. Puente-Martínez A, Ubillos-Landa S, Echeburúa E, Páez-Rovira D. Factores de riesgo asociados a la violencia sufrida por la mujer en la pareja: una revisión de metaanálisis y estudios recientes. 2016;32(1):295-306. Disponible en http://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0212-97282016000100034 [ Links ]

4. Aggleton P, Parker R. World AIDS Campaign 2002-3. A Conceptual Framework and Basis for Action. HIV/AIDS Stigma and Discrimination. Ginebra: UNAIDS; 2002. Disponible en https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/jc891-wac_framework_en_0.pdf [ Links ]

5. Fraser N, Honneth A. Redistribución o reconocimiento. Madrid: Morata; 2006. [ Links ]

6. Alonso A, Cerezo A, Pagés RA, Ramos K, Torricelli V. Informe de situación sobre VIH y violencia basada en el género: una aproximación desde los determinantes sociales. Guatemala: ONUSIDA; 2011. Disponible en https://www.paho.org/gut/index.php?option=com_docman&view=download&category_slug=9-derechos-humanos-y-salud&alias=445-informe-de-situacion-sobre-vih-y-violencia-basada-en-genero&Itemid=518 [ Links ]

7. Maeri I, El Ayadi A, Getahun M, Charlebois E, Akatukwasa C, Tumwebaze D, et ál. "How can I tell?" Consequences of HIV status disclosure among couples in eastern African communities in the context of an ongoing HIV "test-and-treat" trial. AIDS Care-Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV. 2016; 28(Suplemento 3):59-66. Disponible en https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09540121.2016.1168917 [ Links ]

8. Arévalo-Mora L. Mujeres víctimas de violencia de pareja en el contexto de la infección por VIH en la ciudad de Bogotá. Fase I, 2017. Revista de Salud Pública. 2019; 21(1): 34-41. Disponible en http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0124-00642019000100034 [ Links ]

9. Márquez JF, Rivera S, Reyes I. Desarrollo de una escala de estilos de apego adulto para la población mexicana. Revista Iberoamericana de Diagnóstico y Evaluación Psicológica. 2009; 2(28): 9-30. Disponible en https://www.aidep.org/sites/default/files/2018-12/r281.pdf [ Links ]

10. Padilla JA, Díaz-Loving R. Evaluación del apego en adultos: construcción de una escala con medidas independientes. Enseñanza e Investigación en Psicología. 2016; 21(2): 161-168. Disponible en https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/292/29248181006.pdf [ Links ]

11. Arévalo-Mora L. Experiencias y narrativas de mujeres con vih. Víctimas de violencia de pareja en Bogotá (Colombia). Medicina. 2019; 41(4): 299-321. Disponible en https://revistamedicina.net/ojsanm/index.php/Medicina/article/view/1469 [ Links ]

12. Rangel YY. La violencia sexual como limitante en la percepción y gestión de riesgo frente al VIH en mujeres parejas de migrantes. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem. 2016; 24: 1-8. Disponible en http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1518-8345.1141.2782 [ Links ]

13. Drezett J, Baldacini I, Nisida IV, Nassif VC, Nápoli PC. Estudo da adesão à quimioprofilaxia anti-retroviral para a infecção por HIV em mulheres sexualmente vitimadas. Revista Brasileira de Ginecologia e Obstetrícia. 1999; 21(9): 539-544. Disponible en https://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?pid=S0100-72031999000900007&script=sci_arttext [ Links ]

14. Barros C, Schraiber LB, França-Junior I. Association between intimate partner violence against women and HIV infection. Revista de saude publica. 2011; 45(2): 365-372. Disponible en http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0034-89102011005000008. [ Links ]

15. Porto JR, Homero MN, Luz AM. Violence against woman and the female increase of HIV/AIDS incidence. Online Braz J Nurs. 2003; 2(3). Disponible en http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_nlinks&ref=000118&pid=S0103-2100201300020000900017&lng=en [ Links ]

16. Blanco M, Armada F. Las mujeres no esperamos más: Acabemos la violencia contra la mujer y el VIH/SIDA ya. Buenos Aires: Publicación para América Latina y el Caribe; 2007. Disponible en http://www.feim.org.ar/pdf/LO_QUE_SE_MIDE_IMPORTA2008.pdf [ Links ]

17. Bianco M, Mariño A, Re MI. Violencia contra las mujeres y vih/sida en cuatro países del Mercosur. Estadísticas, políticas públicas, legislación y estado del arte. Ciudad de Buenos Aires: Fundación para Estudio e Investigación de la Mujer; 2009. Disponible en http://feim.org.ar/pdf/publicaciones/Informe_Regional_violencia.pdf [ Links ]

18. Vidal F, Carrasco M, Pascal R. Mujeres Chilenas viviendo con VIH/SIDA: derechos sexuales y reproductivos. Santiago de Chile: Vivo Positivo, FLACSO y Universidad ARCIS; 2004. Disponible en http://www.feim.org.ar/pdf/blog_violencia/chile/MujeresChilenas_con_VIH_y_DSyR.pdf [ Links ]

19. Juan-Martínez B, Rangel YY, Castillo-Arcos LD, Cacique L. Ser mujer indígena, vivir con VIH y violencia de pareja: una triple vulneración frente al derecho a la salud. Index de Enfermería. 2018; 27(3): 161-165. Disponible en http://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1132-12962018000200012 [ Links ]

20. Rodríguez LM, Rodríguez-Castro Y, Lameiras M, Carrera MV. Violencia en parejas Gays, Lesbianas y Bisexuales: una revisión sistemática 2002-2012. Comunitania: Revista Internacional de Trabajo Social y Ciencias Sociales. 2017; 13: 49-71. Disponible en http://revistas.uned.es/index.php/comunitania/article/view/18946/0 [ Links ]

21. Saldivia C, Faúndez B, Sotomayor S, Cea, F. Violencia íntima en parejas jóvenes del mismo sexo en Chile. Última Década. 2017; (46):184-212. Disponible en https://scielo.conicyt.cl/pdf/udecada/v25n46/0718-2236-udecada-25-46-00184.pdf [ Links ]

22. Pons D, Atienza FL, Balaguer I, García-Merita ML. Propiedades psicométricas de la Escala de Satisfacción con la Vida en personas de la tercera edad. Revista Iberoamericana de Diagnóstico, Evaluación Psicológica. 2002; 13: 71-82. Disponible en https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2002-18447-005 [ Links ]

23. Cienfuegos YI. Validación de dos versiones cortas para evaluar violencia en la relación de pareja: perpetrador/a y receptor/a. Psicología Iberoamericana. 2014; 22(1): 62-71. Disponible en https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/1339/133944229008.pdf [ Links ]

24. Zamalloa ER. Elaboración y validación de una escala de homofobia en estudiantes universitarios de una universidad privada de Lima Este. PsiqueMag. Revista Científica Digital de Psicología. 2017; 6(1): 245-255. Disponible en http://revistas.ucv.edu.pe/index.php/psiquemag/issue/view/214/Psiquemag%202017-17 [ Links ]

25. Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social [IMSS]. Norma que establece la disposición para la investigación en salud en el Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social 2000-001-009; 2017. Disponible en http://www.imss.gob.mx/sites/all/statics/profesionalesSalud/investigacionSalud/normatividadInst/2000-001-009.pdf [ Links ]

Received: July 07, 2020; Accepted: October 05, 2020

texto en

texto en