Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Enfermería Global

versión On-line ISSN 1695-6141

Enferm. glob. vol.22 no.71 Murcia jul. 2023 Epub 13-Nov-2023

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/eglobal.549801

Originals

Violence against people with disabilities living in rural context: perspectives of health managers

1Nurse at the Hospital Divina Providência, Frederico Westphalen/RS, Brazil

2PhD in Nursing, Professor at the Department of Health Sciences of the Federal University of Santa Maria – Campus Palmeira das Missões. Palmeira da Missões/RS, Brazil

3Nurse. Master’s student in Health and Rurality at the Federal University of Santa Maria – Campus Palmeira das Missões. Palmeira das Missões/RS, Brazil

4Nurse at the Hospital São João Batista, Nova Prata/RS, Brazil

Objective:

To analyze the perspectives of health managers about the violence experienced by people with disabilities living in a rural context.

Material and method:

A descriptive-exploratory study with a qualitative approach, developed in nine municipalities in the north/northwest region of the State of Rio Grande do Sul, in which 18 health managers participated.

Results:

The first category reveals the conception of violence by participants, which is characterized by maltreatment, abandonment, neglect and lack of care. The second category addresses the weaknesses in the conduct of actions and the ways to qualify health work, associated with health planning, professional training and work through the Health Care Network

Conclusions:

Faced with the conceptions, it was evidenced that violence remains invisible in the rural context. This highlights the importance of comprehensiveness and health actions for the implementation of public policies for victims of violence living in the rural context.

Keywords: People with Disabilities; Violence; Public Policies; Health Manager; Nursing Research

INTRODUCTION

Violence is not one, it is multiple, and the term comes from the word vis, which means force and refers to the notions of embarrassment and use of superiority over the other. Considered a socio-historical phenomenon that accompanies the evolution of humanity, it affects individual and collective health and, for its confrontation, requires the formulation of specific policies, as well as the organization of practices and services(1). In health, violence reduces the quality of life of people and the community, poses problems for services and requires prevention and treatment, with multiprofessional and intersectoral action, since every injury and threat to life is part of the field of public health(2),(3).

Due to vulnerable social structures and isolation in the rural context, people with disabilities (PWD) can experience various situations of violence. Associated with the exclusion conditions to which they are exposed(4), such as limited availability and accessibility to health services, low quality of services provided, lack of transport, large geographical distances, limited knowledge and the difficulty of communication and information, this has an impact on their performance and quality of life(5).

Violence in rural context acquires multiple forms and is potentiated, since most services are located in urban areas. In addition, factors that make the problem unfeasible and natural are associated with lack of resources, difficulty in accessing police stations, health services, social assistance and lack of protection of rights(6).

In response to invisibility, the implementation of public policies, the support of managers, financial resources, comprehensive care and intersectoral collaboration stand out(7). In this perspective, health managers are responsible for the transformation, in the health field, of living conditions of PWD, in the implementation and management of public policies(8) and in the care thought in the Health Care Network (RAS)(9), so that health care is focused on the reality of the territory, expanding comprehensive care to this population(10).

The care through comprehensiveness assumes the condition of principle and model of action of the Unified Health System (UHS), in the care of victims of violence in the rural context. Thus, it is associated with the effort of professionals and managers of health services involved in meeting demands related to the suffering generated by violence(11) , in an effective way, and structured through basic guidelines that ensure the promotion, prevention, treatment and rehabilitation of health to victims of violence based on comprehensiveness(12).

In view of the particularities of PWD in rural areas, the aggravation of violence in this context and the numerous challenges regarding inequalities in access to services, reporting the experiences of this population may contribute to the development of prevention strategies, assistance and routing of violence in this scenario. In this perspective, this study focuses on the conceptions of managers regarding the issues of violence directed to PWD living in rural areas, since they are important subjects regarding the articulation of health actions, health planning and implementation of public policies for PWD that suffer violence in the rural context. Therefore, it is proposed to answer the following research question: What are the conceptions and actions of health managers about violence and people with disabilities living in rural context?

Thus, this study aims to: analyze the perspectives of health managers about the violence experienced by people with disabilities living in rural context.

MATERIAL AND METHOD

This is a descriptive-exploratory study with a qualitative approach. The qualitative method applies to the study of history, relationships, representations, beliefs, perceptions and opinions resulting from the interpretations that humans make of themselves, their ways of living and building their artifacts, as well as their feelings and thoughts(13). Exploratory research seeks to provide greater familiarity with the research problem. Descriptive research aims to describe the characteristics of a given population or phenomenon, and may identify possible relationships between variables(14).

The study was conducted in nine municipalities in the north and northwest regions of the State of Rio Grande do Sul (RS), Brazil. These municipalities are located in the area covered by two Regional Health Coordinations (RHC), one of them located in Palmeira das Missões and the other in Frederico Westphalen, corresponding to the 15th and 2nd Health Macroregions. We chose to develop this study in municipalities with more than 70% of the rural population, according to the last demographic CENSUS(15). In this sense, the municipalities belonging to the 15th CRS were part of the sample, being Gramado dos Loureiros, Lajeado do Bugre, São Pedro das Missões and Palmeira das Missões, and the residents belonging to the 2nd CRS: Liberato Salzano, Alpestre, Felling, Pinheirinho do Vale and Frederico Westphalen. Palmeira das Missões and Frederico Westphalen were included because they represent the headquarters of the CRS.

The research was conducted with 18 participants, seven municipal health managers, seven nurses responsible for the Family Health Strategy (FHS) units, two state representatives of public policies for PWD and two state health managers. The inclusion criteria used for the selection of participants were: being working for more than six months in the management position in the health area and working with the theme of public policies for people with disabilities. As an exclusion criterion: be on vacation or leave of any kind during the data collection period.

The possible participants were contacted via telephone for the presentation of the project proposal and the invitation. After acceptance, they were contacted again, to schedule the interviews according to their availability.

Data were collected from December 2019 to February 2020. The collection was made by semi-structured interview, through a guide script with questions related to the problematic of the study, contemplating all the hypotheses, and allowing the interlocutor to have flexibility in the conversations(13). The interviews were conducted individually by the researcher, in the workplaces of the professionals, in an environment with the greatest possible privacy. Each interview lasted approximately 25 minutes. They were recorded by recording in MP3, from the consent of the participants, and then transcribed in full.

For data analysis, we opted for Content Analysis, the best known to represent the treatment of data in a qualitative research, being a research technique that allows making replicable and valid inferences about data from a given context, which consists of three stages(13). In the first stage, which corresponds to the pre-analysis, there was the choice of documents to be analyzed and the resumption of the initial objective of the research. This step was performed through three steps: the floating reading, constitution of the corpus and formulation and reformulation of the objective(13). Initially, it was made the transcription in full of the data obtained from the MP3 recordings of the semi-structured interviews, in the text editor Word version 2013 and after, this material was organized in the Excel 2013 spreadsheet to facilitate the systematization and constitution of the corpus for analysis. Then, there was the floating reading, which allowed to generate initial impressions about the material from the interviews. Subsequently, a sequence of detailed readings was performed, highlighting, through chromatic analysis, the passages in which the participants’ speeches were similar.

In the second stage, Material Exploration took place. To do so, it was initially performed the clipping of common information found in the content of the transcribed speeches, allowing to list the units of record, which refer to words, phrases and expressions that give meaning to the content of the speeches and support the definition of the categories. In this phase, the first step comprised the search for the themes - nuclei of meaning - that composed the units of record.(13)) After finding these units, it became possible to define the two thematic categories.

The last and third stage was the Treatment of Obtained Results and Interpretation, in which the raw results were submitted to simple statistical operations that allowed to highlight the information obtained. At this stage, the researcher made interpretations about the results, based on the objective of the research, interrelating them with the theory(13). This study followed the legislation that addresses the research with human beings, expressed through Resolution n. 466, of December 12, 2012, of the National Health Council. The research project was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Santa Maria (CEP/UFSM), through the Certificate of Presentation for Ethical Assessment (CAAE) number 69973817.4.0000.5346.

The interviews were conducted after signing the Informed Consent Form (ICF) by all participants in the research. The ICF was written in two copies, according to the rules expressed in the resolution, remaining one of them with the research participant, which will guarantee: the freedom to abandon the research at any time and without prejudice to you, privacy, anonymity, commitment to up-to-date study information and assurance that all your questions will be clarified. In order to meet the ethical aspects, the privacy of managers was respected, ensuring and clarifying that the data obtained will be used exclusively for scientific purposes, and their anonymity preserved. For this, we used the nomenclature (P), participant, and the respective number, which respected the order of the interviews.

RESULTS

The participants’ mean age was 41.8 years, being 56% female and 44% male. Regarding schooling, 44% had incomplete elementary school and 56% had completed higher education. As for the graduated professionals, 58% were graduated in nursing; 14% in administration; 7% in psychology; 7% in fonoaudiology; 7% in social work; and 7% in accounting sciences.

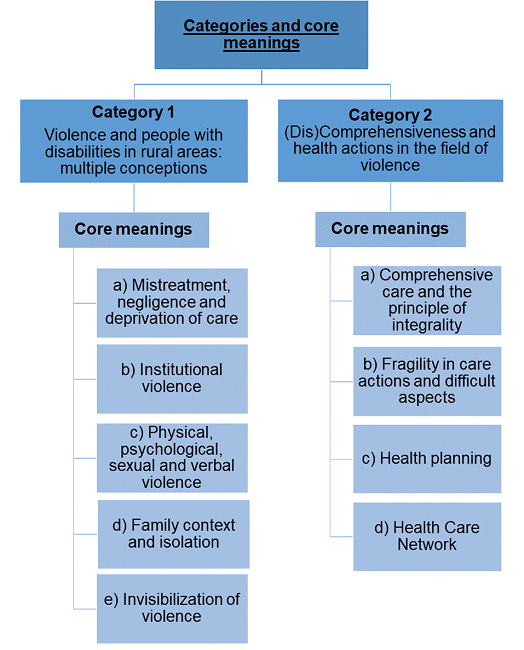

Two categories emerged from the data analysis: “Violence and people with disabilities in rural areas: multiple conceptions” and “Non-integratility and health actions in the field of violence”. Figure 1 illustrates the organization of the categories and the respective nuclei of meaning.

Violence and people with disabilities in rural areas: multiple conceptions

The first category to be presented refers to the conception of the participants about the violence and the PWD living in rural context. This category consists of five nuclei of meaning: a) Abuse, neglect and deprivation of care; b) Institutional violence; c) Physical, psychological, sexual and verbal violence; d) Family context and isolation; e) Invisibilization of violence.

In the conception of the participants of the research, the violence was understood by the maltreatment to this population, as well as neglect and deprivation of care:

I observe a lot and I think there are many mistreatments in rural areas. (P1)

In the conception of these participants, violence is related to the lack of daily life care, such as hygiene and bathing.

I believe that violence is even you leaving a bedridden without a bath, for me it’s a violence, you get it? (P7)

Dirty type, with poor hygiene, happened to bring to the health unit and have to cut nail, do hygiene, because it was half abandoned. (P5)

Institutional violence manifests itself as a barrier that compromises assistance to PWD, despite advances in legislation and public policies. In the following statements, it was possible to identify institutional violence, being represented by the participants by the lack of care.

Just failing to attend is already an aggression. Lack of care, I think it is the greatest violence today. (P11)

In addition to the reported conceptions, the types of violence suffered by PWD living in this context were referred to in the conceptions of the participants. They cited physical, psychological, sexual and verbal violence.

In rural areas, I believe there is also physical, psychological and sexual violence. (P18)

Verbal violence, because sometimes you insult someone, offend someone. (P10)

In the conception of the participants, in the family context violence often occurs due to the difficulty of accepting the PWD, since they are not prepared to live together and face the issues that involve the lived of this person, as expressed in the following statements:

It often happens by the own family, which is the big problem of the family not accepting what the person has. (P14)

Sometimes it is the family member who does this violence, because he is not prepared to face this situation. (P16)

Participants also recognized that violence occurs in all contexts. In the rural context, violence refers to social isolation.

It is an abuse, an abuse of the person, whether in the rural or not, but in the rural, because he is more isolated and such. (P15)

These conditions contribute negatively for PWD to have worse living conditions and health, which puts this population in a scenario of multiple violence. However, it was identified in the speeches of some participants the invisibility of violence against PWD in the rural context.

There is no such violence. We have no cases. (P3)

There are no data, so there are no cases of violence. (P18)

It is observed, in the conception of the participants, that the PWD living in the rural experience the different forms of violence. However, for some participants violence remains invisible, being a way to transform the problem into something distant or invisible in this scenario, contributing to these issues intensify in rural areas and in the lives of PWD.

Non-integrality and health actions in the field of violence

The second category is related to nonintegrality and health actions in the field of violence. This category consists of four nuclei of meaning: a) Integral care and the principle of integrality; b) Fragility in care actions and difficult aspects; c) Health planning; d) Health Care Network.

For participants, comprehensive care refers to considering the patient as a whole, taking into account their conditions, needs and the context in which they live, enabling a set of actions.

I think full attention would be that, you observe the patient as a whole, in the environment he lives, his conditions and what actions he could do to change the situation. (P4)

The principle of integrality is one of the pillars of the SUS. It is observed, in the speeches of the participants, the knowledge about the meaning of comprehensiveness, its importance and the action in coping with violence to the PWD living in rural context.

Comprehensiveness we see people as a whole, right, the holistic question of the situation. It is extremely necessary to follow, to evaluate, to offer better conditions, especially that violence does not happen, right. (P6)

As much as there was knowledge about the concept of integrality on the part of the participants, it occurs that, in practice, there was fragility in the conduct of care actions that consider this principle and in the implementation of public health policies. That’s what the following line says:

We do not have programs aimed at people with special needs for rural areas. (P16)

The testimony indicates that participants were unaware of the existing public policies for PWD in situations of violence in the rural context, which weakens actions through comprehensive care. In addition, talking about the problem of violence is talking about a “not worrying” demand, which contributes to the issue of violence remains hidden.

Actions do not have specific ones, because the demand is not worrying. (P13)

This fragility, when looking at violence, highlights the aspects that hinder the actions that guide the integral care in health services focused on cases of violence against PWD. The participants pointed out that the deficit of professionals, support and lack of professional training corroborate with some of the difficult aspects that impair the direction of the principle of integrality.

It is essential that you have more professionals. It is important that the municipality supports the issue of the manager. (P5)

Trained professionals. (P7)

As for health planning, this was mentioned by the participants as a way to qualify health work and better address the issues of violence against this population, which is demonstrated in the following speech:

We fail a little in the matter of planning. In a matter of planning the network to work better. (P1)

Actions in the field of violence are carried out by a set of services and professionals that make up the care network. Among these services, participants cited social assistance, Reference Center for Social Assistance (CRAS - Centro de Referência de Assistência Social, in Portuguese), Tutelary Council and the police, and among the professionals cited the social worker, psychologist, doctor and nurse.

Social worker, the CRAS who go, who visit, who guide. (P2)

It involves assistance, police, advice. (P13)

Psychologist, nurse, comes the doctor, so it is a regional action to meet these people against violence. (P10)

According to the participants, when cases of violence occurred, they sought to meet with the team and activated the attention network to solve them. In general, the process happened with the report of the situation among the team, which was passed on to the network, which determined which actions would be taken.

In this case, we always have the team, the network, we always try to trigger the CRAS staff, so from the moment the agent reports that someone is suffering some kind of violence, will trigger the entire network, will forward, will try to attend. (P1)

In this perspective, it is observed that the conduct of health actions by managers is not conFigured effectively, highlighting the need for health planning, implementation of public policies, to meet the singularities of violence faced by PWD in rural areas.

DISCUSSION

As for the objective of the study, the results show the participants’ perspectives regarding violence and health care actions. In the first category, participants pointed out their conceptions regarding violence against PWD in rural areas and how these issues make life and health difficult for this population. Regarding the conceptions, the participants indicated the forms of violence to which this population is subjected and the contexts in which it occurs.

As for the reported maltreatment, in the conception of the participants, these are associated with all forms of violence, most cases occurring within the family context and in any disability. Maltreatment, when produced by family members, has an impact on the conduct, perception and power of PWD(16), which can negatively affect the psychological and social fields, leading to illness(17).

Participants’ conception of violence is related to neglect and deprivation of care. Such conceptions meet what is pointed out by Minayo(18), which classifies this violence as absence or refusal of care to those who should receive attention, in this case, the PWD. In addition, a study(16)) carried out in a municipal public network, with students with visual impairment, revealed cases of family neglect associated with abandonment and suppression of basic needs, such as poor hygiene, hunger and cold situations that elucidate the precariousness of care and care experienced by PWD.

Corroborating the findings, PWD in rural areas live invisible, without access to essential services, including health services. Some participants mentioned, in their conceptions, that the lack of care is conFigured in violence to this population, which refers to institutional violence, which is manifested by action or omission in public services(19). This is presented as lack of access to services, low quality of services provided and unequal relationships between professionals and users, practiced by those who, in theory, should pay humanized attention and be a primary source of health care(20).

Physical, psychological, sexual and verbal violence are experienced in the context of life of PWD and were indicated in the participants’ conceptions. These violence in the rural context are potentiated, since the lack of accessibility to public services constitutes them as exclusion spaces, since these services are located in urban areas, leading PWD to face barriers that prevent displacement(6).

In the family context, the presence of a PWD in the family may be linked to negative feelings and uncertainties, triggering difficulties in family relationships. An international study in rural India, with people with disabilities, showed that physical, emotional, economic stress and care overload trigger violent postures on the part of family members, such as threats and physical violence(21).

Violence is transformed even more potentiated in the rural environment, by the singularity, anonymity and isolation of the PWD, as referred to in the conception of the participants, for being a context of adversity and exclusion, beyond the geographical distance from the urban area and essential services(11). An international study carried out in Finland has shown that the supply of services in rural areas is diminished by the geographical issue which, in addition to the long distance, includes the lack of accessibility to precarious spaces, associated with the lack of development in this context, unlike the urban environment, which is associated with easy access to services, social, cultural activities and public transport for commuting(22).

Aggravating the situation, violence is invisibilized, silenced and naturalized in health services and in the participants’ speeches(23). Moreover, PWD in rural contexts have difficulties in accessing police stations and social assistance, which hinders complaints and contributes to the invisibility of the problem(24). This issue in health services is due to the lack of training to detect violence, lack of investment and professional support(23)) or is yet another way to transform this phenomenon into something distant.

The second category deals with nonintegrality and care actions in the field of violence, pointing out the weaknesses in the conduct of care actions and ways to qualify health work. The participants corroborated with the findings in the literature(12), which discuss the comprehensiveness as one that allows actions of promotion, prevention, protection and recovery of health, guaranteeing to the victims of violence the continuous care in the different and presupposes the articulation of health through public policies(12), in order to ensure quality of life and meet needs.

In the speeches, contradictory aspects were identified, because, although the participants knew the importance of integrality in the field of violence, there was fragility in the conduct of actions. These questions demonstrate the existing failures in the structuring of services and dehumanization in care, which motivates the obstacles in the search for assistance(25).

Regarding public policies, some participants were unaware of existing health policies for victims of violence in the rural context. This suggests that there are no public policies in this scenario, since most services are concentrated in the urban context(26), preventing health care from occurring through the principle of integrality. Regarding public policies for PWD, the lack of knowledge of participants stems from the lack of training and articulation of health services, since the National Health Policy for People with Disabilities reinforces that health professionals should be updated, trained and qualified for the development of prevention, detection, intervention and appropriate referrals for PWD(27), which did not occur in the contexts studied.

The difficult aspects of actions through comprehensiveness focused on cases of violence against PWD are related to the lack of professionals, support and lack of professional training. In the international context, the scenario is repeated. A study conducted in Malawi with PWD living in rural areas highlighted the inefficiency and lack of trained professionals in health units to work with this population, constituting a direct barrier to access to health care(28).

To qualify health work and better address issues of violence, health planning was mentioned by the participants. It is a fundamental management instrument for compliance with the guidelines that guide the UHS and that contributes to the organization of the public health services network, through it, it is possible to face the problems and develop actions that meet the population(29).

With regard to coping actions in the field of violence, participants indicated a set of services and professionals for care and referral in cases of violence and that make up the care network. RAS are organizational arrangements of health services integrated through support and management systems, seeking to ensure the integrality of care(9). One study pointed out the importance of networking through the intersectoral approach in coping with the problem of violence, since the absence of care network generates isolation and overload for professionals, being enhanced by the characteristics of rurality(30).

Thus, PHC can act as an articulator of the social sectors, including health, education, social assistance, justice and as a proposer of comprehensive health care performed in network for cases of violence, ensuring comprehensiveness and intersectorality in care(12). Given the above, it reflects on the importance of health actions for PWD through comprehensiveness, aiming at care in all its complexity, ensuring public policies that meet the needs. In addition, services and professionals who constitute the RAS for PWD victims of violence in rural areas, in order to provide adequate care and referral.

CONCLUSIONS

Given the perspectives of the participants, the findings and discussions about violence allow to show that this phenomenon remains invisible in this context, even being recognized by the participants. Thus, it is mentioned that the conception of violence is based on the life contexts of this population associated with their disability, which motivates maltreatment, abandonment and neglect. These issues may reflect the difficulties of managers to understand the needs of PWD, resulting in the absence of resources, perpetuating invisibility and the absence of interventions on the events of violence.

Although health managers recognize the importance of comprehensiveness, it was identified that there are difficulties for the effectiveness, in health services, associated with the lack of actions and referrals in situations of violence, the absence of health planning, professionals, and even the difficulty of access by PWD to health services.

This research presents intrinsic limitations of descriptive qualitative studies, but reveals important data to think about health strategies and actions, in order to ensure comprehensive care for PWD. Still, there is a lack of studies that discuss violence against PWD in rural areas, with approaches that consider the conceptions of health managers and actions.

Thus, it is recommended the development of future studies to make PWD visible in situations of violence in rural areas, given the complexity of this problem in this scenario and the consequences on life and health of this population.

Funding Source:National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq - Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico), called FAPERGS/MS/CNPQ/SESRS n. 03/2017- Research Program for the UHS: shared health management. Research project entitled “Social Determinants of Health in People with Disabilities, Families and Support Network in the Rural Scenario: multiple vulnerabilities”, for financial support.

REFERENCES

1. Minayo MCS. A inclusão da violência na agenda da saúde: trajetória histórica. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva [internet]. 2007 [citado 2022 mar 19]; 11(suppl):1259-1267. Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/j/csc/a/vM4c5NGrjxPFj8Phv4Mghjw/?lang=pt. [ Links ]

2. Lopes DTV, Oliveira MR, Souza TH, Pereira SP. Violência contra a mulher: uma problemática de saúde pública. Revista Ibero-Americana de Humanidades, Ciências e Educação [internet]. 2021 [citado 2022 ago 26]; 7(10): 2675 - 3375, 2021. Disponível em: https://www.periodicorease.pro.br/rease/article/view/2704. [ Links ]

3. Minayo MCS, Souza ER, Silva MMA, Assis SG. Institucionalização do tema da violência no SUS: avanços e desafios. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva [internet]. 2018 [citado 2022 mar 19]; 23(6):2007-2016, 2018. Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/j/csc/a/Q3kCPCWfBzqh8mzBnMhxmYj/. [ Links ]

4. Sikweyiya Y. et al. Intersections between disability, masculinities, and violence: experiences and insights from men with physical disabilities from three African coutries. BMC Puclic Health [internet]. 2022 [citado 2022 ago 26]; 22(705), 2022. Disponível em: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-022-13137-5. [ Links ]

5. Dassah E, Aldersey H, McColl MA, Davison C. Factors affecting access to primary health care services for persons with disabilities in rural areas: a "best-fit" framework synthesis. Glob Health Res Policy [internet] 2018 [citado 2022 ago 26]; 3:36, 2018. Disponível em: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30603678/. [ Links ]

6. Bueno ALM, Loper MJM. Rural women and violence: readings of a reality that approaches fiction. Ambiente & Sociedade [internet]. 2018 [citado 2022 mar 19]; 21:e01511. Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/j/asoc/a/VVNcs38qHFGC5q3yvh8xPzj/abstract/?lang=en. [ Links ]

7. Organización Mundial De La Salud (OMS). Resumen: Respuesta a la violencia de pareja y a la violencia sexual contra las mujeres [internet]. 2014 [citado 2022 mar 19]. Disponível em: https://iris.paho.org/bitstream/handle/10665.2/7705/WHORHR13_10_esp.pdf?ua=1. [ Links ]

8. Dubow C, Garcia EL, Krug SBF. Percepções sobre a Rede de Cuidados à Pessoa com Deficiência em uma Região de Saúde. Saúde em Debate [internet]. 2018 [citado 2022 ago 26]; 42(117):455-467, 2018. Disponível em: https://www.scielosp.org/article/sdeb/2018.v42n117/455-467/. [ Links ]

9. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Portaria nº 4.279, de 30 de dezembro de 2010. Estabelece diretrizes para a organização da Rede de Atenção à Saúde no âmbito do Sistema Único de Saúde (SUS). Diário Oficial da União [internet], Brasília (DF). 30 dez 2010 [citado 2022 mar 19]. Disponível em: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/gm/2010/prt4279_30_12_2010.html. [ Links ]

10. Ministério da Saúde (BR), Portaria nº 793, de 24 de abril de 2012. Institui a Rede de Cuidados à Pessoa com Deficiência no âmbito do Sistema Único de Saúde [Internet]. Brasilia; 2012 [citado 2022 ago 26]. Disponível em: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/gm/2012/prt0793_24_04_2012.html. [ Links ]

11. Costa MC, Lopes MJM. Elements of comprehensiveness in the professional health practices provided to rural women victims of violence. Revista Escola de Enfermagem da USP [internet]. 2012 [citado mar 19]; 46(5):1088-1095. Disponível em: https://www.revistas.usp.br/reeusp/article/view/48129. [ Links ]

12. Mendonça CS, Machado DF, Almeida MAS, Castanheira ERL. Violência na Atenção Primária em Saúde no Brasil: uma revisão integrativa da literatura. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva [internet]. 2020 [citado 2022 mar 19]; 25(6):2247-2257, 2020. Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/j/csc/a/5GyqvZVTTXQLnSbVwcZ6QvL/?lang=pt. [ Links ]

13. Minayo MCS. O Desafio do Conhecimento: pesquisa qualitativa em saúde. 14. ed. São Paulo: Hucitec, 2014. 416 p. [ Links ]

14. Gil AC. Como Elaborar Projetos de Pesquisa. 4. Ed. São Paulo: Atlas, 2008. [ Links ]

15. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Sinopse do Censo Demográfico 2010 [internet]. 2010 [citado 2022 mar 19]. Disponível em: https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/sociais/populacao/9662-censo-demografico2010.html?edicao=9673&t=sobre. [ Links ]

16. Saccol LRI, Vianna C, Pavão SMO. Negligência Familiar: Implicações na Aprendizagem Escolar de Estudantes com Deficiência Visual. Revista Brasileira de Educação Especial [internet]. 2021 [citado 2022 ago 26]; 27:e0014, 2021. Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/j/rbee/a/dGTDDgBCC4wjqy4nrNYQWFp/abstract/?lang=pt#. [ Links ]

17. Carvalho AMF, Lopes RE, Oliveira EM, Nunes JM. O suporte social como estratégia de enfrentamento de pessoas com deficiência frente a situações de violência. Revista de Pesquisa Cuidado é Fundamental Online [internet]. 2018 out/dez; [citado 2022 mar 19]; 10(4): 991-997. Disponível em: https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/portal/resource/pt/biblio-916064. [ Links ]

18. Minayo MCS. Violência e saúde. 20. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Editora FIOCRUZ, 2006. Disponível em: http://books.scielo.org/id/y9sxc/pdf/minayo-9788575413807.pdf. [ Links ]

19. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Secretaria Nacional de Enfrentamento à Violência contra as Mulheres. Secretaria de Políticas para as Mulheres. Política Nacional de Enfrentamento à Violência Contra as Mulheres. Ministério da Saúde [internet], Brasília (DF). 2011 [citado 22 mar 19]. Disponível em: https://www12.senado.leg.br/institucional/omv/entenda-aviolencia/pdfs/politica-nacional-de-enfrentamento-a-violencia-contra-as-mulheres. [ Links ]

20. Taquette S. et al. Mulher adolescente/jovem em situação de violência [internet]. Secretaria Especial de Políticas para as Mulheres. Brasília (DF). 2007 [citado 2022 mar 19]. Disponível em: https://bvssp.icict.fiocruz.br/pdf/mul_jovens.pdf [ Links ]

21. Mathias K, Kermode M, Sebastian MS, Davar B, Goicolea I. Na asymmetric burden: Experiences of men and women as caregivers of people with psycho-social disabilities in rural North India. Transcult Psychiatry [internet] 2018 [citado em 2022 ago 26]; 56(1):76-102, 2018. Disponível em: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30141376/. [ Links ]

22. Verma I, Taegen J. Access to services in rural areas from the point of view of older population- a case study in Finland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health [internet]. 2019 [citado 2022 mar 19]; 2;16(23):4854. Disponível em: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31810348/. [ Links ]

23. Moreira GAR, Vieira LJES, Cavalcanti LF, Silva RM, Feitoza AR. Manifestações de violência institucional no contexto da atenção em saúde às mulheres em situação de violência sexual. Saúde e Sociedade [internet]. 2020 [citado 2022 mar 19]; 29(1):e180895. Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/j/sausoc/a/YHkQDt7KQRYzbbYVh3Nw7mc/?lang=pt. [ Links ]

24. Hirt MC, Costa MC, Arboit J, Leite MT, Hesler LZ, Silva EB. Representações sociais da violência contra mulheres rurais para um grupo de idosas. Revista Gaúcha de Enfermagem [internet]. 2017 [citado 2022 mar 19]; 38(4):e68209. Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/j/rgenf/a/Tz3YkZnVJSYzKV5P99xvSVh/abstract/?lang=pt. [ Links ]

25. Silva JG, Branco JGO, Vieira LJES, Brilhante AVM, Silva RM. Direitos sexuais e reprodutivos de mulheres em situação de violência sexual: o que dizem gestores, profissionais e usuárias dos serviços de referência? Saúde e Sociedade [internet]. 2019 [citado 2022 ago 26]; 28(2):187-200, 2019. Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/j/sausoc/a/XNLndLPPwYqW6Gh9TjZq8Cn/?lang=pt&format=html. [ Links ]

26. Borth LC, Costa MC, Silva EB, Fontana DGR, Arboit J. Rede de enfrentamento à violência contra mulheres rurais: articulação e comunicação dos serviços. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem [internet]. 2018 [citado 2022 mar 19]; 71(suppl 3):1287-94. Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/j/reben/a/VSvhjkhwScCXzSVsR6kPjry/?lang=pt. [ Links ]

27. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Política Nacional de Saúde da Pessoa com Deficiência. 1ª ed. Brasília (DF): Ministério da Saúde [internet]. 2010 [citado 2022 mar 19]. Disponível em: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/politica_nacional_pessoa_com_deficiencia.pdf. [ Links ]

28. Harrison, JAK. Access to health care for people with disabilitier in rural Malawi: what are the barriers? BMC Public Health [internet]. 2020 jun; [citado 2022 mar 19]; 1;20(1):833. Disponível em: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32487088/. [ Links ]

29. Ferreira J, Celuppi IC, Baseggio L, Geremia DS, Madureira VSF, Souza JB. Planejamento regional dos serviços de saúde: o que dizem os gestores? Saúde e Sociedade [internet]. 2018 [citado 2022 mar 19]; 27(1):69-79. Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/j/sausoc/a/6XdxDvqvLzKXWjTHNgZTdCp/abstract/?lang=pt. [ Links ]

30. Mapelli LD, Sabino FHO, Costa LCR, Silva JL, Ferriani MGC, Carlos DM. Rede intersetorial para o enfrentamento da violência contra crianças e adolescentes em contexto de ruralidade. Revista Gaúcha de Enfermagem [internet]. 2020 [citado em 2022 ago 26]; 41:e2019046. Disponível em: https://seer.ufrgs.br/index.php/rgenf/article/view/109939. [ Links ]

Received: November 30, 2022; Accepted: April 16, 2023

texto en

texto en