Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Medicina Oral, Patología Oral y Cirugía Bucal (Internet)

versión On-line ISSN 1698-6946

Med. oral patol. oral cir.bucal (Internet) vol.12 no.4 ago. 2007

Gingival neurofibroma in a neurofibromatosis type 1 patient. Case report

José Antonio García de Marcos1, Alicia Dean Ferrer2, Francisco Alamillos Granados3, Juan José Ruiz Masera4, María Jesús García de Marcos5, Alfredo Vidal Jiménez6, Borja Valenzuela Salas7, Ana García Lainez7

(1) Consultant. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Department. Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Albacete. Albacete

(2) Consultant. Head of Section. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Department. University Hospital "Reina Sofía". Córdoba, Spain.

Fellow of the European Board of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. Associated Professor in the School of Medicine. Cordoba University

(3) Consultant. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Department. University Hospital "Reina Sofía". Córdoba, Spain.

Fellow of the European Board of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. Associated Professor in the School of Medicine. Cordoba University

(4) Consultant. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Department. University Hospital "Reina Sofía". Córdoba

(5) Stomatologist. Private practice. Madrid

(6) Resident. Pathology Department. University Hospital "Reina Sofía". Córdoba

(7) Resident. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Department. University Hospital "Reina Sofía". Córdoba

ABSTRACT

Neurofibroma is a benign peripheral nerve sheath tumour. It is one of the most frequent tumours of neural origin and its presence is one of the clinical criteria for the diagnosis of type 1 neurofibromatosis (NF-I). Neurofibromatosis type 1 is an autosomal dominantly inherited disease due to an alteration in the long arm of chromosome 17. About 50% of NF-I patients have no family history of the disease. NF-I patients have skin lesions (café au lait spots and neurofibromas) as well as bone malformations and central nervous system tumours. Diagnosis is based on a series of clinical criteria. Gingival neurofibroma in NF-I is uncommon. Treatment of neurofibromas is surgical resection. The aim of this paper is to report a case of NF-I with gingival involvement and to review the literature.

Key words: Type I neurofibromatosis, NF-I, neurofibroma, Von Recklinghausens disease, gum.

RESUMEN

El neurofibroma es un tumor benigno, de los nervios periféricos, desarrollado a partir de la vaina neural. Representa uno de los tumores de origen neurógeno más frecuente y es uno de los criterios clínicos de diagnóstico de neurofibromatosis tipo 1 (NF-I). La NF-I es una enfermedad genética producida por una alteración en el brazo largo del cromosoma 17. La mitad de los casos tienen antecedentes familiares y el 50% son mutaciones nuevas. Los pacientes con NF-I principalmente presentan lesiones en la piel (manchas café con leche y neurofibromas), así como malformaciones óseas y tumores del sistema nervioso central. El diagnóstico de la enfermedad se basa en una serie de criterios clínicos. La aparición de neurofibromas en la encía en pacientes con NF-I es poco común El tratamiento de los neurofibromas es la escisión quirúrgica. El objetivo de este artículo es presentar un caso de NF-I con afectación neurofibromatosa de la encía maxilar, diagnosticado y tratado quirúrgicamente en nuestro Servicio de Cirugía Oral y Maxilofacial y realizar una revisión de la literatura.

Palabras clave: Neurofibromatosis tipo I, NF-I, neurofibroma, enfermedad de Von Recklinghausen, encía.

Introduction

Neurofibroma is a benign peripheral nerve sheath tumour (1-6). Neurofibromas arise from Schwann cells and perineural fibroblasts (1,3-5,7,8). They may appear in patients with or without hereditary neurofibromatosis; in this last case they are called solitary neurofibromas (5). Two clinical forms of neurofibromatosis have been described: peripheral, type I (NF-I); and central, type II (NF-II) (1,5,8,9). These are two different diseases both from the clinical as the genetic point of view. (1,9).

NF-I, also known as Von Recklinghausens disease, is a neurodermal dysplasia, first described by the pathologist Friederich Daniel Von Recklinghausen in 1882 (8,9). The pathologic alterations that define the disease begin in the embryogenic period, prior to the differentiation of the neural crest (9-11). NF-I is more frequent (90% of cases) than NF-II. It is manifested mainly by skin lesions (café au lait spots, multiple neurofibromas), as well as by bone malformations and central nervous system tumours (1,5,8-10). It is the most frequent genetic human disease, affecting 1:3000 newborn and one of every 200 inhabitants with mental retardation (1,8-10,12).

The genetic alterations are localized in the long arm of chromosome 17 (9). NF-I is an autosomal dominantly inherited genetic disorder with a penetrance of almost 100% and a variable expression.

However, about 50% of cases are sporadic as a consequence of spontaneous mutations. The disease has one of the highest rates of spontaneous mutations within the genetic diseases (1,5,6,8-13). There is no preference for gender or race in NF-I (1,9,10). Diagnosis of NF-I is based on clinical criteria (4,10) (Table 1).

In NF-II skin is generally less affected and bilateral acoustic neurinomas with or without central nervous system tumours constitute its main characteristic. Diagnosis is based on clinical criteria (5,14) (Table 1). NF-II (1:50.000) is less common than NF-I (1:5.000) and its genetic alteration is localized in the long arm of chromosome 22 (5,9,14).

20 to 60 % of oral neurofibromas are associated with neurofibromatosis. Oral neurofibromas are present in about 25 % of neurofibromatosis patients. Gingival affectation is rare (6).

We report a case of a maxillary gingival neurofibroma in a NF-I patient.

Case report

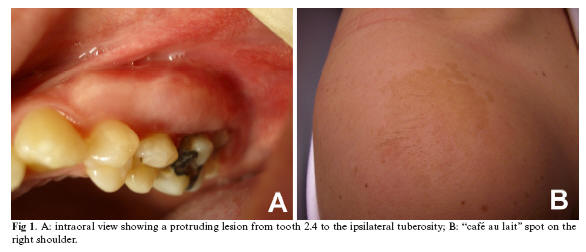

A 21-year-old woman was referred to our department by her dentist for the evaluation of a two years evolution slow growing gingival hypertrophy. The lesion was soft and painless to palpation. It was located in the upper jaw and protruded in the buccal sulcus from the bicuspid region to the tuberosity (Fig.1.A). An orthopantomography showed no bony lesion. Seven years before the patient had had a neurofibroma resected in her left preauricular area. More than six café au lait spots over 15 mm diameter could be seen throughout her skin (Fig. 1.B). Axillary and inguinal freckles were also present. A NF-I was diagnosed based on these clinical criteria. The patient had no familiar history of NF-I. Under local anesthesia the lesion was partially resected and tooth 28 was extracted. Only the vestibular part of the lesion was resected, and the extension to the pterygopalatine fossa was left intact. Pathological report showed a neurofibroma (Fig.3). After eighteen months there are no signs or symptoms derived from the lesion.

Discussion

NF-I is due to an alteration of the NF-I gene. This gene is a tumour suppressor gene located in the long arm of chromosome 17 (17q11.2) (1,10,12). The loss of this genes function due to a mutation determines an increase in cell proliferation and the development of tumours (1).

Pigmented lesions are a common manifestation in NF-I. These lesions usually appear during the first years of life or are present at birth, either as café au lait spots or as freckles (1,4,5,9,10). Café au lait spots are hyperpigmented maculae that may vary in color from light brown to dark brown Their borders may be smooth or irregular. They may appear anywhere on the skin, but they are less common on the face (1). Inguinal and axillary freckles (Crowe´s sign) are frequently present (1,5). The patient here reported had more than six café au lait spots and bilateral axillary and inguinal freckles.

Multiple skin neurofibromas as well as angiomas are also characteristic in NF-I (1,9,10). There exist two main clinical forms of neurofibroma: localized and plexiform neurofibromas. Localized neurofibroma is the most frequent one in NF-I. It develops along a peripheral nerve as a focal mass with well defined margins. It is rarely present at birth but appears in late childhood or early adolescence (1). The number of localized neurofibromas generally increases with age, and there is an increase in size and number of the lesions during pregnancy and puberty (1,5). Although skin is the predominantly affected organ, some others such as stomach, bowels, kidney, urine bladder, larynx or heart may become affected. In the head and neck, the most frequently affected sites are scalp, cheek, neck and oral cavity (1). Plexiform neurofibroma spreads along the peripheral nerve and may affect some nervous rami (1,12). This is a poorly-circumscribed and locally invasive tumour (12). About 21% of patients with NF-I are affected with plexiform neurofibromas (10). Morbidity of plexiform neurofibromas in NF-I is high since they tend to grow until reaching a great size and producing disfigurement. Besides, the risk of malignization is between 2 and 5% (1,12).

Due to its diffuse involvement / appearance and soft consistence, palpation of neurofibroma is similar to that of lipoma, vascular malformation, lymphangioma or rhabdomyoma (5).

Bone involvement in NF-I may be due both to external resorption and to internal osteolytic defects. External resorption may be due to the pressure applied on the bone by the neurofibroma, as it happens in the case here reported (Fig.2: B and C) (1,5). It is well known that in NF-I bone malformations such as kyphoscoliosis or pseudoarthrosis may appear, and the TMJ may be involved (5,9,11). Skeletal involvement is present in almost 40 % of patients with NF-I, being scoliosis the most common skeletal pathology (8,10,11).

Iris hamartoma, acoustic neurinoma, central nervous system tumours (glioma, glioblastoma), macrocephaly and mental retardation (up to 40% of cases) can also be found (9,10).

Oral cavity involvement appears in 66%-72% of the cases of NF-I. Lengthening of fungiform papillae happens in 50% of cases and is the most frequent finding. In 25% of neurofibromatosis patients oral neurofibromas can be seen. There is no racial, gender or age predilection for the development of oral neurofibromas in NF-I. Neurofibromas may appear in every tissue, soft or hard, in the oral cavity. The most commonly affected site is the tongue (1,2,6,7,9,10). In the case here reported the neurofibroma was located in the gum, which is not a common location (1,6). Shapiro et al. state that gum involvement by neurofibroma in NF-I patients is 5% (referenced in Cunha el al. (1)). Localized oral neurofibromas usually appear as asymptomatic nodules covered by normally coloured mucosa (1,4,6,9). However, when adjacent to cranial nerves, they can impair motor function of facial or hypoglossal nerves or the sensitivity of trigeminal nerve (1,4,6). Gingival neurofibromas may cause dental malposition or impaction (1,9). In the case here reported the second molar could not erupt completely, and the wisdom tooth was totally included. NF-I patients may also show facial disfigurement due to hypo or hyperplasia of maxilla, mandible, malar bone and TMJ. Facial plexiform neurofibromas may also cause a facial asymmetry (1,10). Exophthalmos may also be present due to a dysplasia of the sphenoid major wing.

Radiological findings in oral neurofibromas include mandibular channel, mandibular foramen and mental foramen widening (1,9). Neurofibromas may seldom be primarily intraosseous; in that case they usually appear as a unilocular, well-defined radiolucency (1,6,7). In the case here reported no radiological alterations were found. Most neurofibromas show low attenuation in CT scans, although some of them may show soft tissue density. Low density lesions contain a variable amount of Schwann cells, which are rich in lipids, cystic degeneration and xanthomatous alterations. High density areas are thought to represent collagen rich or cellular areas. In MRI, lesions show a low signal in T1 and a high signal in T2, with a variable highlighting with the contrast (8). A high peripheral signal with a low central signal in T2 weighted images (bulls eye sign) is a typical sign of neurofibromas (6,8). A similar sign can be seen in CT; in this case there is a central high signal (8).

Histologically, neurofibromas are composed of a mixture of Schwann cells, perineural cells, and endoneural fibroblasts, and they are not capsulated (2,5,15). Schwann cells account for about 36 to 80% of lesional cells. These constitute the predominant cellular type and they usually have widened nuclei with an undulated shape and sharp corners. On electric microscopy Schwann cells can be seen embracing axons. These can be highlighted with silver or acetylcholinesterase staining or with immunohistochemical techniques when using the optic microscope. It is estimated that between 0,7% and 31% of cells are perineural cells. In seldom cases this type of cells can predominate (15).

Neurofibromatous lesions usually evolve slowly, without pain, but during growth, puberty or pregnancy their evolution may be accelerated (9).

Total or partial resection of neurofibromatous lesions is the treatment of choice to solve aesthetic or functional problems; it is advisable to wait for treatment until growth has been completed thus diminishing the risk of recurrence (4,6,9,10). Total resection with 1 cm margins whenever feasible is the treatment of choice for accessible and small tumours (5). Radiotherapy or chemotherapy are not recommended for treatment (5,9). Thalidomide has been used to treat pain in plexiform neurofibromas (4). There is no evidence that surgery favours malignant transformation. Malignant transformation rate of neurofibromas in NF-I is 3 to 5 % (1,9,10).

NF-I patients must receive genetic counselling since this is an autosomal dominantly inherited disease and the likelihood of transmission to the children is 50% in both sexes (1). Malignant transformation to neurofibrosarcoma bears a very bad prognosis and distant metastases are frequent, being the mean survival of 15% at 5 years. Some authors state that recurrence may appear after surgical resection and that multiple recurrences increase the risk for malignant transformation (6).

It is important that oral and maxillofacial surgeons and dentists keep this disease under consideration when oral lesions characteristic of NF-I are present. These patients must be reviewed long term because of eventual complications, especially that of malignant transformation.

References

1. Cunha KS, Barboza EP, Dias EP, Oliveira FM. Neurofibromatosis type I with periodontal manifestation. A case report and literature review. Br Dent J 2004;196:457-60. [ Links ]

2. Go JH. Benign peripheral nerve sheath tumor of the tongue. Yonsei Med J 2002;43:678-80. [ Links ]

3. García de Marcos JA, Ruiz Masera JJ, Dean Ferrer A, Alamillos Granados FJ, Zafra Camacho F, Barrios Sánchez G, et al. Neurilemomas de cavidad oral y cuello. Rev Esp Cir Oral Maxilofac 2004;26:384-92. [ Links ]

4. Gómez Oliveira G, Fernández-Alba Luengo J, Martín Sastre R, Patiño Seijas B, López-Cedrún Cembranos JL. Neurofibroma plexiforme en mucosa yugal: Presentación de un caso clínico. Med Oral 2004;9:263-7. [ Links ]

5. Marx RE, Stern D, eds. Oral and maxillofacial pathology. A rationale for diagnosis and treatment. Illinois: Quintessence Publishing Co, Inc; 2003. [ Links ]

6. Bhattacharyy I, Cohen D. Oral neurofibroma. Abril 2006 (citado 5 junio 2006). "www.emedicine.com/derm/topic674.htm". [ Links ]

7. Apostolidis C, Anterriotis D, Rapidis AD, Angelopoulos AP. Solitary intraosseous neurofibroma of the inferior alveolar nerve: report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2001;59:232-5. [ Links ]

8. Hillier JC, Moskovic E. The sof tissue manifestations of neurofibromatosis type 1. Clin Radiol 2005;60:960-7. [ Links ]

9. Bekisz O, Darimont F, Rompen EH. Diffuse but unilateral gingival enlargement associated with von Recklinghausen neurofibromatosis: a case report. J Clin Periodontol 2000;27:361-5. [ Links ]

10. Bongiorno MR, Pistone G, Aricò M. Manifestations of the tongue in Neurofibromatosis type 1. Oral Dis 2006; 12:125-9. [ Links ]

11. Singh K, Samartzis D, An HS. Neurofibromatosis type I with severe dystrophic kyphoscoliosis and its operative management via a simultaneous anterior-posterior approach: a case report and review of the literature. Spine J 2005;5:461-6. [ Links ]

12. Lin V, Daniel S, Forte V. Is a Plexiform Neurofibroma Pathognomonic of Neurofibromatosis Type I? Laryngoscope 2004;114:1410-4. [ Links ]

13. Ferner RE, Hughes RA, Hall SM, Upadhyaya M, Johnson MR. Neurofibromatous neuropathy in neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1). J Med Genet 2004;41:837-41. [ Links ]

14. Pletcher BA. Neurofibromatosis, type 2. Marzo 2006 (citado 9 Julio 2006); "www.emedicine.com/neuro/topic496.htm". [ Links ]

15. Ide F, Shimoyama T, Horie N, Kusama K. Comparative ultrastructural and immunohistochemical study of perineurioma and neurofibroma of the oral mucosa. Oral Oncol 2004;40:948-53. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Dr. J.A. García de Marcos.

C/ Antonio Acuña. Nº10.5ºAizq.

28009. Madrid, Spain

E-mail: pepio2@hotmail.com

Received: 8-09-2006

Accepted: 20-04-2007