Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Anales de Psicología

versión On-line ISSN 1695-2294versión impresa ISSN 0212-9728

Anal. Psicol. vol.32 no.3 Murcia oct. 2016

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.32.3.217751

Early symbolic comprehension of a digital image as a source of information and as a mean of communication

La comprensión simbólica temprana de una imagen digital como medio de comunicación y fuente de información

Daniela Jauck and Olga Peralta

Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas - CONICET (Argentina).

Instituto Rosario de Investigaciones en Ciencias de la Educación -IRICE (Argentina).

This study was funded by a grant from CONICET PIP 0876 awarded to Olga A. Peralta and by a doctoral fellowship from the same agency awarded to Daniela E. Jauck.

ABSTRACT

Graphs, photographs, digital images, are very much present in children's lives from very early, accomplishing a variety of functions. In this research we explore the symbolic comprehension of a digital image provided by a Tablet as a mean of communication and as a source of information by 24-month-old children. We used two tasks. In the first, children had to indicate in the image the localization where they have observed the experimenter hid the toy in a small room. In the second, children had to search for an object in the room guided by the image in which the experimenter indicated the location where the object was hidden. We found that children utilized the image as a source of information to guide their search, but not as a mean of communication to inform the localization to someone else. However, after a brief experience in the utilization of the image as a source of information, children successfully used it as a mean of communication. The results show that for young children using the image of the Tablet as a source of information not only is simpler but also has facilitating effects in its use as a mean of communication.

Key words: early symbolic development; images; Tablet; means of communication; sources of information.

RESUMEN

Gráficos, fotografías, imágenes digitales, están muy presentes en la vida de los niños desde muy temprano cumpliendo una diversidad de funciones. En esta investigación exploramos la comprensión simbólica de una imagen digital provista por una Tablet como medio de comunicación y como fuente de información por parte de niños de 24 meses. Utilizamos dos tareas, en la primera los niños debían indicar en la imagen el lugar donde habían visto al experimentador esconder un objeto en una habitación pequeña. En la segunda, los niños debían buscar un objeto en la habitación guiados por una imagen en la que se les señalaba el escondite. Encontramos que los niños utilizaron la imagen como fuente de información para guiar la búsqueda, pero no como medio de comunicación para indicar a otro el escondite. Sin embargo, tras una experiencia breve en la utilización de la imagen como fuente de información, lograron utilizarla como medio de comunicación. Los resultados muestran que para los niños pequeños el empleo de la imagen de una Tablet como fuente de información no solo es más sencillo, sino que tiene efectos facilitadores en su empleo como medio de comunicación.

Palabras clave: desarrollo simbólico temprano; imágenes; Tablet; medio de comunicación; fuente de información.

Introduction

An important feature of human cognition consists in learning and communicating information through a variety of symbolic objects available in the cultural environment; among these symbolic objects, images occupy a prominent role. Symbolic objects are not just cognitive tools; they also change cognition completely expanding the here and now and allowing to operate on absent, present and even nonexistent realities (DeLoache, 2004; Martí, 2003; Rivière, 1990; Tomasello, 1999, 2000).

Signs, labels, drawings, videos, photographs, flood our environment. These images fulfill a multitude of functions. Understanding their symbolic nature and learning to use them is an important challenge in the first years of life.

The images provided by digital devices (phones, Tablets, cameras, computers) are increasingly present in everyday life. Despite its use by young children has been questioned by researchers and pediatricians (e.g. American Academy of Pediatrics, 2011; Radesky, Schumacher & Zuckerman, 2015; Wartella & Robb, 2008), these images are starting to be employed in various educational contexts, so they have begun to function as a new scaffold in learning (Barr, 2013; Dickerson & Meltzoff, 2009; Kirkorian & Pempek, 2013; Richet, Bobb & Smith, 2011; Zack, Barr & Gerhardstein, 2009).

Whether the use of these devices is recommended or not for young children, a central question for teaching is whether they understand the symbolic function of their images. The main goal of this paper was to study 24-month-old children's understanding and use of symbolic images provided by a Tablet in in two tasks: as a source of information and as a mean of communication. We also investigated whether previous experience in one task had an impact on the subsequent execution of the other.

As very young children recognize and even name the objects represented, differentiate images from their real counterparts discriminating images from referents, it was often assumed that they understand the symbolic relationship that unites them to what they represent (e.g. Dirks & Gibson, 1977; Rose, 1977).

These observations have contributed to the formation of a mistaken interpretation considering that babies "understand images symbolically", almost automatically. As Sigel (1978) had already indicated a long time ago, this interpretative error stems from not distinguishing perception and recognition from symbolic understanding. Understanding an image symbolically implies appreciating their dual nature (DeLoache, 1987; 2004).

An explanation about the origin of the difficulties in understanding images, and symbolic objects in general, has precisely focused on their dual nature, as they are objects in their own right as well as representations of another entity. To understand and use a symbolic object, mental representations of both aspects of its dual reality are needed: their physical characteristics and the abstract relationships with what they depict. Young children do not show this cognitive flexibility, they see the symbol as a concrete and attractive object in itself, which prevents from seeing through it to its referent (Ittelson, 1996).

Some studies (DeLoache & Marzolf, 1992; DeLoache, 1991 Uttal, O'Doherty, Newland, Hand & DeLoache, 2009) revealed that three-dimensional symbolic objects, such as replicas or scale models, are harder to be taken as symbols than images. One possible explanation is that as threedimensional objects are more attractive for children, they tend to focus on the concrete object itself which interferes with the access to its referent (DeLoache, 1991).

Although images also have concrete and material features, they are much less salient as objects than threedimensional objects. This reduced saliency favors paying more attention to their representational nature than to their physical features. It is likely, too, that two-dimensional objects trigger to a lesser extent sensorimotor schemes linked to manipulation, so, they are more likely to be treated as objects of contemplation and reflection than of action (Gelman, Chesnik & Waxman, 2005; Gelman, Waxman & Kleinberg, 2008; Striano, Tomassello & Rochat, 2001). Therefore, the construction of a double symbolic representation of three-dimensional objects is difficult because children must inhibit sensory-motor schemes that are activated whenever a manipulative object enters the space (Tomasello, 2000). In this regard, it has even been shown that if the child is allowed to manipulate a symbolic object, its symbolic accessibility is even more affected (DeLoache & Marzolf, 1992; Uttal, O'Doherty, Newland, Hand & DeLoache, 2009).

Several factors have also been postulated to act together, influencing symbolic understanding, such as developmental factors related to age, symbolic experience, symbol-referent similarity, and to the amount and type of instruction received (DeLoache, Peralta & Anderson, 1999). The type of instruction refers to the information provided about symbolreferent correspondence and the intention with which someone is using the symbolic object. Correspondence and intentionality have been described as two major paths towards understanding of symbolic objects (Peralta & Salsa, 2011; Salsa & Peralta, 2007).

Concerning correspondence, research in analogical reasoning suggested that structural alignment and one-to-one parallelism can provide a deeper insight in cognitive processes (e.g., Gentner & Markman, 1997; Namy & Gentner, 1999). That is, superficial symbol-referent comparisons between entities and events can eventually lead to symbolic understanding (DeLoache, 2002; Namy & Gentner, 2002). With respect to intentionality, a representation is informative about a reality only because someone has proposed so (Bloom & Markson, 1998; Callaghan, 2005; DeLoache, 2004; Sharon, 2005; Tomasello & Carpenter, 2007). It is only due to the intention of the producer and/or the user that a symbol is relevant as a tool in a task. Therefore, an important aspect in the understanding of a symbolic object involves recognizing the intention with which it is being used.

The present research explored 24-month-old children's symbolic understanding and use of an image provided by a Tablet as a source of information and as a mean of communication. We used two tasks, in the first, the child had to solve a problem (finding a hidden object) using the information supplied by the image; in the second, the child had to inform an observed situation (the concealment of an object) using an image. In addition, we were interested in finding out whether previous experience in one task had an influence in the subsequent execution in the other.

The design of the tasks was based on the search task used by DeLoache and Burns (1994). In this task, the experimenter hid a toy in a room without the child observing, then showed the child a picture indicating the location of the toy and asking the child to find the toy using the information provided by the picture. This task, with several variations, has been used as research tool in many studies testing the understanding of symbolic objects. This task bares high ecological validity, as in western cultures children are quite familiar with games where objects and people hide, finding them very attractive. Also, the resolution of this task requires little verbal skills, which makes it particularly suitable when working with young children.

An important body of research clearly established that at 24-months-of-age children do not use pictures or images in video as a source of information to find a hidden object (DeLoache, 1987; DeLoache & Burns, 1994; Peralta & Salsa, 2011; Schmitt & Anderson 2002; Troseth & DeLoache, 1998). Later studies have also showed that a previous successful experience using images symbolically has a positive influence on a subsequent more difficult task (Peralta & Salsa, 2009; Troseth, 2003), illustrating a transfer effect. Previous experience has been proposed as a mechanism that promotes symbolic sensitivity, that is, "a general expectation or willingness to search and detect symbolic relationships between entities" (DeLoache, 2002, p. 216).

It is relevant to note that in the study of DeLoache and Burns (1994) there was a condition in which a Polaroid camera was used. In this condition the performance of the children improved, although not significantly. It seems that this manipulation somewhat highlighted the symbolic function of the photograph emphasizing photograph -room correspondence as well as the intention with which the image was being used in the task, as a representation of reality.

As far as using an image as a mean of communication, Peralta (Peralta & DeLoache, 2004; Peralta & Salsa, 2009) designed a task with a somehow reverse procedure. In this task the researcher hid the toy somewhere in the room while the child observed, then, requested the child to indicate the hiding location of the toy in a photograph of the room. It was found that two-year-old children indicated in the photograph what they had observed in reality and after this experience they used the photograph as a source of information in the classical search task.

In the present research we used a Tablet, due to its characteristics this device enables live recording of a situation and can "freeze reality" capturing an image that remains on the screen. One might think that the production of the image by this device significantly improves the advantages that the Polaroid camera offered in comparison with a traditional photograph.

Using a Tablet, the image, the device that produces it, the producer and the production process occur simultaneously. These considerations led us to postulate that this device could not only accentuate the reality-image correspondence, but also highlight the intention of representation on the part of the user, the experimenter.

The main purpose of this research was to explore 24-month-old children's symbolic understanding and use of images of a Tablet, as means of communication and as sources of information. Due to the characteristics of the Tablet and the mode of production of its images, we postulate that this device facilitates the symbolic understanding and use of images by this age children.

Method

Participants

Twenty four 24-month-old children participated (M = 24.58; SD = 0.97), 12 girls and 12 boys. Children were contacted through the kindergartens they attended. In all cases informed consent from parents and institutions was required. The socioeconomic level of the participants can be considered as medium. All parents had completed high school; most of them had tertiary or university studies and worked in their professions or in commerce. A few mothers were housewives.

Materials

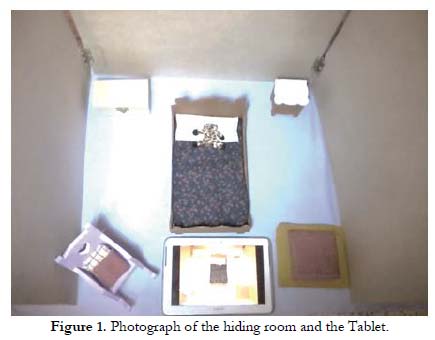

A portable room (1m high x 80cm depth x 1m width) furnished as a bedroom served as a hiding room. It contained a bed, a box, an armchair, a bed side table and some cushions. The object to be hidden was a little doll named Lily. We used a Tablet (10.1") configured to produce a light flash and a sound when capturing an image (Figure 1).

Procedure

For this study we adapted two tasks previously used. On one hand, the classical search task by DeLoache (DeLoache, 1987; DeLoache & Burns, 1994). This task consisted in a simple game; the experimenter hid a toy in a room (e.g. under the bed), showed to the child in the image where she hid it and then the child had to find the object in the room based on the information provided by the image: Search task. On the other hand, we adapted the task designed by Peralta (Peralta & DeLoache, 2004; Peralta & Salsa, 2009) where the child had to point/show/indicate in a picture the location where she or he had seen an object being hidden by the experimenter: Indicate task. The tasks consisted of four subtests, in each the toy was hidden in four of five different possible locations (bed, cushions, box, armchair and bedside table). The children were randomly assigned to two groups according to the order of presentation of the tasks. Half of the children solved first Indicate and then Search (Group 1: 23-26 months; M = 24.58 months, SD = 0.90, 4 girls and 8 boys) and the other half the other way round, Search-Indicate (Group 2: 23-26 months, M = 24.58 months, SD = 1.08; 8 girls and 4 boys). The order of presentation of the four hiding locations was counterbalanced, the fifth possible location served to prevent from choosing by discard.

The procedure consisted of two phases:

1. Orientation and demonstration. The purpose of this phase was to familiarize the child with the materials and the type of activities that were going to be carried out in the test. The experimenter showed the child the toy to be hidden (Lily), then she named the different hiding locations of the room (bed, box, bedside table, cushions and armchair) placing the doll in each one. Then she showed the Tablet to the child inviting him or her to take two pictures of different objects and one of the entire room. It was essential for the child to observe the Tablet. Then, in order to explicitly mark the correspondences, the experimenter placed the Tablet with the image on the screen by the piece of furniture saying, "Look at this photo of Lily's armchair and this is Lily's armchair". Finally, to explain the intention with which the images were going to be used, she proceeded to put the doll in a certain place (e.g., on the bed.), took a picture with the Tablet and said, "This picture shows you where Lily is; remember that the photo will tell you where Lily is!".

2. Test. Once the orientation was completed the test phase began, this phase consisted of two tasks.

2.1 Indicate. The experimenter hid Lily somewhere in the room with the child looking at the hiding event. Then, she took a picture of the entire room and invited the child to stand aside, where he or she could not observe simultaneously the room and the image of the Tablet. Afterwards she asked, "Can you show me in the picture where Lily is hiding?" Immediately after indicating the location in the picture, the child had to find the toy in the room. This last step controlled memory because the child may have failed to indicate in the image simply due to not remembering where the toy had been hidden.

2.2 Search. The experimenter told the child, "Now I'll hide Lily somewhere in her house but you do not have to look, then I'll show you in the photo where she is and you'll look for her". Once Lily was hidden, the experimenter and the child took a picture of the entire room with the Tablet. The experimenter indicated in the image of the Tablet the hiding place without naming it, and said: "Lily is hidden here (e.g. pointing to the bed), shall we look for her in her house?".

Strategy of analysis

The dependent variable on which the analyses were carried out was the number of correct responses in the four subtests of the two tasks. It was only considered the first choice. Each child could have a score from 0 to 4 in each of task, and from 0 to 8 considering both tasks. Analyses were performed on the number of correct responses; percentages are also reported for clarity purposes.

Children's perseverative responses were coded as it has been repeatedly reported that the most common error in this type of tasks is to select the previous hiding place (O'Sullivan, Mitchell & Daehler, 2001; Schmidt, Crawley-Davis & Anderson, 2007; DeLoache & Sharon, 2003; Suddendorf, 2003). It was also taken into account the correct searches in the memory test of the task Indicate.

Analyses of the individual performance based on the criterion of successful participant were also performed. We considered the child as successful if he/she had correctly answered at least 3 of the 4 subtest of each task.

Due to the size of the sample and since no normality was assumed, we opted for a non-parametric analysis using the Mann-Whitney U test for independent samples (between groups) and Wilcoxon Z for related samples (within groups).

Results

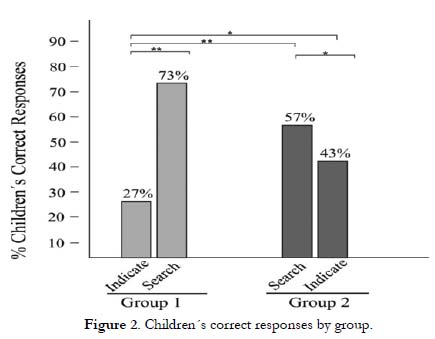

Children's responses within and between groups were compared. Figure 2 shows the percentage of children's correct answers in Indicate and Search by group; that is, according to the order of presentation of the tasks. Group 1: Indicate-Search, Group 2: Search-Indicate.

Analyses intra group

In Group 1 (Indicate-Search) it was found that the children's correct responses in Indicate (27%) were significantly lower than in Search (73%) (Z = -2.61;p < .009).

In Group 2 (Search-Indicate), significant differences between children's correct responses in both tasks were found, Search (57%) versus Indicate (43%) (Z = -1.99;p < .04).

Analyses between groups

As far as the first task presented in each group (Indicate G1 vs. Search G2), we found that the correct responses in Search (G2, 57%) were significantly higher than in Indicate (G1, 27%) (U = 25.00; p < .006). This results show that without prior experience in, children show a better execution in Search than in Indicate.

With respect to Indicate G2 (43%) versus Indicate G1 (27%), correct answers were higher in Group 2 (U = 40.00; p <0.05), which shows that when children have a brief experience in the search task, their performance in indicating the hiding location in the image significantly improves.

Concerning Search G1 (73%) vs. Search G2 (57%), no significant differences were found. When children began Indicating their subsequent execution in Searching was similar to as when they started Searching. Although previous experience in Indicating improves children's performance in Searching, the improvement is not significant, probably due to the fact that from the very beginning children showed a high performance on this task.

Finally, no significant differences were found between the total correct answers of both groups considering the two tasks together (G, 45% vs. G2, 55%; U = 243; ns).

The overall results show that children were more successful Searching than Indicating.

We also analyzed the individual performance according to the criterion stipulated for successful participant (3 out of 4 correct subtests in each task). In Group 1, Indicate-Search, from a total 12 children, only one met the criteria for successful participant in Indicate while in Search eight did. In group 2, Search-Indicate, seven children out of 12 were classified as successful individuals in Search and five in Indicate. Overall, children were more successful Searching than Indicating. Note that a larger number of children met the criterion for successful subject in Indicating when they had a previous experience in Searching (five) than when they did not have that experience (one).

As for the memory test, it was found that despite not having had a high performance at the time of Indicating the hiding location in the picture, the vast majority of children (93%) searched correctly for the toy in the room. The poor performance in the Indicating task, therefore, was not due to memory problems, that is, having forgotten where they had observed the experimenter hid the toy, but to a failure in the symbolic connection reality-image.

Concerning perseverative responses, it was observed that, contrary to reports in most studies using search tasks, the children showed very few responses either Indicating or Searching in the immediate previous location. Three perseverative responses in G1 and two in G2 were recorded. However, these responses were coded as correct because children immediately self-corrected, without any intervention on the part of the experimenter.

Discussion

This research explored the symbolic understanding and use of images of a Tablet by 24-month-old children in two tasks: as a mean of communication (Indicate) and as a source of information (Search). We found that children did use the image a as a source of information but did not use it as a mean of communication. However, after a brief experience in the search task, they managed to use the image to communicate information.

The results show that for small children the use of an image of a Tablet as a source of information not only proved to be easier, but also had facilitating effects on its use as a mean of communication.

One possible explanation of these results may be due to the properties of the device itself and the features of the tasks. While the image on a Tablet is two-dimensional, the device is three-dimensional. In the search task the experimenter pointed to the hiding location and then put aside the device, out of child's reach and sight, inviting him/her to search in the room. In contrast, in Indicate the experimenter hid the toy with the child looking and then showed the device asking the child to point to the hiding location in the image, so, the Tablet not only remained in sight of the child but he/she could also touch it. In this task it was observed that even some children explored the edges of the Tablet or the screen. As it has been amply demonstrated, children have difficulties understanding symbolic three-dimensional objects in relation to two-dimensional ones and the difficulty increases when they are given the opportunity to explore the object (DeLoache & Marzolf, 1992; Uttal, O'Doherty, Newland, Hand & DeLoache, 2009).

The results concerning the search task, in which children were highly successful, do not agree with previous studies that, using paper or video images, reported that at this age children failed to connect the images with their referents (DeLoache, 1987, 1991; DeLoache & Burns, 1994; Peralta & Salsa, 2011; Schmitt & Anderson, 2002; Troseth, 2003; Troseth & DeLoache, 1998). The findings presented here suggest that a Tablet facilitates the symbolic understanding of images as sources of information.

The images captured by a Tablet also possibly highlight the symbol-referent relationship. When the experimenter took pictures using the Tablet, the child watched the images on the device, which probably underscored its referential function. By capturing the objects of the reality and instantly producing an image, this device may not only have helped children to establish correspondences between real objects and images, but also to capture the intention with which the experimenter was using the images. Ultimately an image is informational in a search task only because the investigator proposes so. As it has been shown, children improve their performance when capturing the purpose with which the symbolic tool being used in a task (Chen & Siegler, 2013; Maita, Mareovich & Peralta, 2014; Roseberry, Hirsh-Pasek & Golinkoff, 2013; Smerville, Hildebrand & Crane, 2008).

It is worth noting that the tasks were presented in two orders. In Group 1 the child indicated first and then searched, in Group 2 the other way around. This was done in order to see both, if children benefited from the experience in the previous task (DeLoache, Simcock & Marzolf, 2004; Marzolf & DeLoache, 1994; Peralta & Salsa, 2003), or if they failed due because the old information interfered with the new one (Ganea & Harris, 2013). The most important result found in this regard was that when the child started Searching, the execution in Indicate improved. The effect of specific symbolic experience has been demonstrated in transfer studies in which children solve tasks of greater symbolic difficulty after having solved a less difficult task. While the children in the present study at first found not easy to use images to communicate a real observed situation, with the prior successful experience in the search task the performance significantly improved. These results are not consistent with a previous study (Peralta & Salsa, 2009) in which with a similar task but using printed pictures on paper children found easier to use the images as a mean of communication than as a source of information.

The discrepancy in these results may be due, in part, to the medium used. Printed pictures are very common in children's lives, being a common practice in early picturebook reading interactions the use of books, photo albums, etc. In these interactions adults use images to communicate information about objects, people or events (e.g. Fletcher & Reese, 2005; Ninio & Bruner, 1978; Peralta, 1995). Thus, the familiarity of children with the communicative function of images on paper possibly facilitates their symbolic use. The images provided by Tablets have only recently begun to be part of children's lives and they are not being used so much to communicate information, as photographs or drawings. As it has been amply shown, the specific characteristics of different symbolic objects have a differential effect on symbolic understanding. In this sense, the images captured on the screen of a Tablet proved to be difficult to understand and use as a mean of communication by young children. Nevertheless, a previous successful experience of children in the search task facilitated a subsequent performance in using the image of a Tablet to communicate information. In future studies it could be interesting to make a direct comparison of the understanding and use of images on paper (photographs, illustrations) versus on Tablets as both, means of communication and sources of information. It is important to note that children made very few perseverative errors. This error has been commonly reported in various studies that have used search tasks with young children (e.g. O'Sullivan, Mitchell & Daehler, 2001; Peralta & Salsa, 2003; Sharon & DeLoache, 2003; Suddendorf, 2003). One possible explanation could be that embedding a picture on the Tablet before each new search helped children to update the information.

Given some of the potential benefits that the images of a Tablet may offer for their use as sources of information by very young children, future studies could be aimed at investigating whether children can learn specific contents through images provided by this device. Also, it would be interesting to study the effects of using a Tablet for learning, not when the adult manipulates the device but allowing the child to do so in order to "discover" and take advantage of the interactive properties of touch screens.

An observation that emerges from this research is that not all images are equal as symbolic means and that, both, their characteristics and modes of production can be important at the time of understanding and using them in a symbolic way.

Acknowledgements

This research is part of the doctoral thesis of the first author under the direction of the second.

The authors wish to thank the children and the institutions that participated.

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Olga A. Peralta,

Instituto Rosario de Investigaciones en Ciencias de la Educación -IRICE.

Boulevard 27 de Febrero 210 bis (Argentina).

E-mail: peralta@irice-conicet.gov.ar

Article received: 16-01-2015

Revised: 25-03-2015

Accepted: 08-06-2015

References

1. American Academy of Pediatrics (2011). Council on Communications and Media. Policy statement on media education. Pediatrics, 126, 1-7. [ Links ]

2. Barr, R. (2013). Memory constraints on infant learning from picture books, television, and touchscreens. Child Development Perspectives, 7 (4), 205-210. [ Links ]

3. Bloom, P. & Markson, L. (1998). Intention and analogy in children's naming of pictorial representations. Psychological Science, 9, 200-204. [ Links ]

4. Callaghan, T. C. (2005). Developing an intention to communicate through drawing. Enfance, 1, 45-56. [ Links ]

5. Chen, Z., & Siegler, R. (2013). Young children's analogical problem solving: Gaining insights from video displays. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 116, 904-913. [ Links ]

6. Deloache, J. S (1987). Rapid change in the symbolic functioning of very young children. Science, 238(4833), 1556-1557. [ Links ]

7. Deloache, J. S (1991). Symbolic functioning in young children: Understanding pictures and models, Child development, 62, 736-752. [ Links ]

8. DeLoache, J. S. (2002). Early development of the understanding and use of symbolic objects. En U. Goswami (Ed.), Blackwell Handbook of Childhood Cognitive Development (pp. 206-226). Malden, MA: Blackwell. [ Links ]

9. DeLoache, J. S. (2004). Becoming symbol-minded. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 8, 66-70. [ Links ]

10. DeLoache, J. S. & Burns, N. (1994). Early understanding of the representational function of pictures. Cognition, 52, 83-110. [ Links ]

11. DeLoache, J.S. & Marzolf, D. P. (1992). When a picture is not worth a thousand words: Young children's understanding of pictures and models. Cognitive Development, 7, 317-329. [ Links ]

12. DeLoache, J. S., Peralta, O. A. & Anderson, K. (1999). Multiple factors in early symbol use: instructions, similarity, and age in understanding a symbol-referent relation. Cognitive Development, 14, 299-312. [ Links ]

13. DeLoache, J. S., Simcock, G. & Marzolf, D. P. (2004). Transfer by very young children in the symbolic retrieval task. Child Development, 75, 1708-1718. [ Links ]

14. Dirks, J. & Gibson, E.J. (1977). Infants' percerception of similarity between live people and their photographs. Child Development, 48, 124-130. [ Links ]

15. Fletcher, K. & Reese, E., Picture book reading with young children: A conceptual framework, Developmental Review, 25, 64-103, 2005. [ Links ]

16. Ganea, P.A., & Harris, P.L. (2013). Early limits on the verbal updating of an object's location. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 114, 89-101. [ Links ]

17. Gelman, S.A., Chesnick, R. & Waxman, S.R. (2005). Mother-child conversations about pictures and objects: Referring to categories and individuals. Child Development, 76(6), 1129-1143. [ Links ]

18. Gelman, S., Waxman, S. & Kleinberg, F. (2008). The role of representational status and item complexity in parent-child conversations about pictures and objects. Cognitive Development, 23, 313-323. [ Links ]

19. Gentner, D. & Markman, A. B. (1997). Structure mapping in analogy and similarity. American psychologist, 52, 45-46. [ Links ]

20. Gentner, D. & Namy, L. L. (1999). Comparison in the development of categories. Cognitive Development, 14, 487-513. [ Links ]

21. Ittelson, W. H. (1996). Visual perception of markings. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 3, 171-187. [ Links ]

22. Liszkowski, U., Carpenter, M., Striano, T., y Tomasello, M. (2006). 12- and 18-month-olds point to provide information for others. Journal of Cognition and Development, 7, 173-187. [ Links ]

23. Kirkorian, H.L. & Pempek, T.A. (2013). Toddlers and touch screens: Potential for early learning? Zero to Three, 33, 32-37. [ Links ]

24. Maita, R. M., Mareovich, F. Peralta, O. A. (2014). Intentional teaching facilitates young children's comprehension and use of a symbolic object. The Journal of Gnetic Psychology: Research and Theory on Human Development, 17 (5) 401-415. [ Links ]

25. Martí, E. (2003). Representar el Mundo Externamente. La Construcción Infantil de los Sistemas Externos de Representación. Madrid: A. Machado / Colección Aprendizaje. [ Links ]

26. Marzolf, D. P., & DeLoache, J. D. (1994). Transfer in young children's understanding of spatial representations. Child Development, 64, 1-15. [ Links ]

27. Namy, L. L. & Gentner, D. (2002). Making a sill purse out of two sow's ears: young children's use of comparison in category learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 131, 5-15. [ Links ]

28. Ninio, A. y Bruner, J. (1978). The achievement and antecedents of labeling. Journal of Child Language, 5, 1-15. [ Links ]

29. O'Sullivan, L., Mitchell, L. L. & Daehler, M. W. (2001). Representation and perseveration: Influences on young children's representational insight. Journal of Cognition and Development, 2, 339-368. [ Links ]

30. Peralta, O. A. (1995). Developmental changes and socioeconomic differences in mother-infant picturebook reading. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 10, 261-272. [ Links ]

31. Peralta, O. A. & DeLoache, J. S. (2004) La comprensión y el uso de fotografías como representaciones simbólicas por parte de niños pequeños. Infancia y Aprendizaje, 27 (1), 3-17. [ Links ]

32. Peralta, O. A. & Salsa, A. M. (2003). Instruction in early comprehension and use of a symbol-referent relation. Cognitive Development, 18 (2), 269-284. [ Links ]

33. Peralta, O. A. & Salsa, A. M. (2009). Means of Communication and Sources of Information: Two-Year-Old Children's Use of Pictures as Symbols. The European Journal of Cognition and Development, 21 (6), 801-812. [ Links ]

34. Peralta, O. A., & Salsa, A. M. (2011). Instrucción y desarrollo en la comprensión temprana de fotografías como objetos simbólicos. Anales de Psicología, 27 (1), 118-125. [ Links ]

35. Radesky, J. S., Schumacher, J. & Zuckerman, B. (2015). Mobile and interactive media use by young children: The good, the bad, and the unknown. Pediatrics, 135 (1), 1-3. [ Links ]

36. Richert, R.A., Robb, M.B. & Smith, E.I. (2011). Media as social partners: The social nature of young children's learning from screen media. Child Development, 82 (1), 82-95. [ Links ]

37. Riviere, A. (1990). Origen y desarrollo de la función simbólica en el niño. En J. Palacios, A. Marchesi y C. Coll (Eds.), Desarrollo psicológico y educación, Vol. I Psicologia Evolutiva (pp. 113-130). Madrid: Alianza Editorial. [ Links ]

38. Rose, A. (1997). Infants' transfer of response between two-dimensional and three-dimensional stimuli. Child Development, 48, 1086-1091. [ Links ]

39. Roseberry, S., Hirsh-Pasek, K. & Golinkoff, R.M. (2014). Skype me! Contingent interactions help toddlers learn language. Child Development, 85 (3), 956-970. [ Links ]

40. Salsa, A.M. & Peralta, O.A. (2007). Routes to symbolization: Intentionality and correspondence in early understanding of pictures. Journal of Cognition and Development, 8 (1), 79-92. [ Links ]

41. Schmitt, K. L. & Anderson, D. R. (2002). Television and reality: Toddlers' use of visual information from video to guide behavior. Media Psychology, 4, 51-76. [ Links ]

42. Schmitt, K. L., Crawley-Davis, A. M. & Anderson, D. R. (2007). Two-year-old's retrieval based on television: Testing a perceptual account. Media Psychology, 9(2), 389-409. [ Links ]

43. Sharon, T. (2005). Made to symbolize: Intentionality and children's early understanding of symbols. Journal of Cognition and Development, 6(2), 163-178. [ Links ]

44. Sharon, T. & DeLoache, J.S. (2003). The role of perseveration in children's symbolic understanding and skill. Developmental Science, 6 (3), 289-296. [ Links ]

45. Sigel, I. E. (1978). The development of pictorial comprehension. En B. S. Randhawa y W. E. Coffman (Eds.), Visual Learning, Thinking and Communication (pp. 93-111). Nueva York: Academic Press. [ Links ]

46. Sommerville, T. F., Hildebrand, E. A. & Crane, C.C. (2008). Experience matters: The impact of doing versus watching on infants' subsequent perception of tool use events. Developmental Psychology, 44, 1249-1256. [ Links ]

47. Striano, T., Tomasello, M. & Rochat, P. (2001). Social and object support for early symbolic play. Developmental Science, 4(4), 442-455. [ Links ]

48. Suddendorf, T. (2003). Early representational insight: Twenty-four-month-olds can use a photo to find an object in the world. Child Development, 74, 896-904. [ Links ]

49. Tomasello, M. (1999). The cultural ecology of young children's interactions with objects and artifacts. En E. Winograd, R. Fivush, y W. Hirst (Eds.), Ecological Approaches to Cognition: Essays in honor of Ulric Neisser (pp. 153-170). Mahawah, N.J.: Erlbaum. [ Links ]

50. Tomassello, M. (2000). The Cultural Origins of Human Cognition. London: Harvard Universtiy Press. [ Links ]

51. Tomasello, M. & Carpenter, M. (2007), Shared intentionality. Developmental Science, 10, 121-125. [ Links ]

52. Troseth, G. (2003). TV guide: Two-year-old children learn to use video as a source of information. Developmental Psychology, 39 (1), 140-150. [ Links ]

53. Troseth, G. L., & DeLoache, J.S. (1998). The medium can obscure the message: Young children's understanding of video. Child Development, 69, 950-965. [ Links ]

54. Uttal, D., O'Doherty, K., Newland, R., Hand, L. & DeLoache, J. (2009) Dual representation and the linking of concrete and symbolic representations. Child Development Perspectives, 3, 156-159. [ Links ]

55. Wartella, E., & Robb, M. (2008). Historical and recurring concerns about children's use of the mass media. En S. L. Calvert & B. Wilson (Eds.), Handbook on Children, Media and Development. 7-26. Boston: Blackwell. [ Links ]

56. Zack, E., Barr, R., Gerhardstein, P., Dickerson, K. & Meltzoff, A. N. (2009). Infant imitation from television using novel touch-screen technology. British Journal of Development Psychology, 27(1), 13-26. [ Links ]

texto en

texto en