Introduction

Bullying is typically defined as an exercise of power designed to intentionally and persistently harm the victims (Harris & Petrie, 2006; Olweus, 2005), who are unable to defend themselves given the passivity and complicity of the group within which it occurs (Díaz-Aguado, Martínez, & Martín, 2013; Salmivalli & Voeten, 2004).

The prevalence of frequent bullying in child populations is estimated to be around 5% (Olweus, 2005). In Spain, a number of studies, such as that published by the Ombudsman Office in 2007 (Del Barrio, Espinosa, & Martín, 2007) or the more recent work by Díaz-Aguado et al. (2013), have found a prevalence of around 4%. Spain however, does not have one of the highest rates of bullying; in Norway, for example, the prevalence in 2008 was estimated to be 6.2% (Roland, 2011), while in the United States 10% of pupils are victims of bullying (Shetgir, Lin, & Flores, 2013). Other international studies have found a prevalence of 12.6% (Craig et al., 2009).

Research has demonstrated that the consequences of being bullied while at school can be significant and have many effects on victims, such as depressive symptoms, anxiety and psychosomatic disorders, which have been described (Andreou, 2000; Prinstein, Boergers, & Vernberg, 2001; Rigby, 2000; Storch & Masia-Warner, 2004). Other studies have reported high levels of perceived stress (Estévez, 2005; Estévez, Murgui, Musitu, & Moreno, 2008; Seals & Young, 2003) and school failure (Garaigordobil & Oñederra, 2010).

It has also been found that the well-being of aggressors is impaired. Bullies have been associated with callous-unemotional traits and impulsivity, long-term behavioural problems, anxiety and depression, but also with high scores on social competence and social status (Fanti & Kimonis, 2012; Swearer & Hymel, 2015). In short, bullying is associated with significant negative impacts on the quality of life of those involved and compromises pupils’ healthy development (Cook et al., 2010).

Bullying has been characterized as a group phenomenon, given that it occurs in interaction with, and with the support of, the group. Hence, the study of bullying requires consideration of intergroup and relational factors (Cerezo, 2009; Gómez et al., 2007). Of these factors, social support has been shown to have a notable influence on general well-being in adolescence (Rueger, Malecki, & Demaray, 2010) and on academic adjustment (Domitrovich & Bierman, 2001; Musitu, Martínez, & Murgui, 2006).

Social support is understood to be the overall set of expressive or instrumental provisions offered by the community, social networks and other significant persons (Lin & Ensel, 1989). Hence, it is of interest to adopt a multidimensional perspective of social support during adolescence, considering family, school and peer group. Adolescence is a life stage in which the relationships with these networks seem to undergo a process of change (Scholte, Van Lieshout, & Van Aken, 2001).

It has been reported that when perceived social support is low, there is a greater risk of receiving, but also engaging in, violent behaviours (Cava, Musitu, & Murgui, 2006; Lambert & Cashwell, 2004; Martínez-Ferrer, Murgui-Pérez, Musitu-Ochoa, & Monreal-Gimeno, 2008; Musitu et al., 2006). In this sense, it has been underlined that both the number (Fox & Boulton, 2006; Wang, Iannotti, & Nansel, 2009) and quality (Kendrick, Jutengren, & Stattin, 2012; Malcolm, Jensen-Campbell, Rex-Lear, & Waldrip, 2006) of friendships can protect from peer bullying and victimization (Yaban, Sayil, & Tepe, 2013; Yubero, Ovejero, & Larrañaga, 2010).

Parental social support has also been studied as a protective factor against bullying. Fanti, Demetriou & Hawa (2012) found that parental support protects adolescents from being cyber-victimized, even when peer group support is low. They also found an association between higher levels of cyber-victimization and adolescents exhibiting a combination of low levels of parental support and peer group support.

As regards the school environment, findings indicate that a supportive school climate protects against victimization (Eliot, Cornell, Gregory, & Fa, 2010; Williams & Guerra, 2007), which occurs more frquently in schools where social support is lower, manifested in poor pupil-teacher interaction (Cook et al., 2010; Veenstra et al., 2005).

As well as perceived support, there is another group factor in the school environment associated with bullying: reputation, how a person is perceived by others. Social reputation refers to the construction of a personal identity based on the image we receive from other significant parties in social interaction. In the case of adolescents, the image received from the group is related to the degree to which an individual is rejected or integrated within a group and appears to be key in regulating social behaviour and configuring self-concept and self-esteem (Cava & Musitu, 2000; Martínez, Moreno, Amador, & Orford, 2011).

It has been shown that the search for a better social reputation may be associated, in adolescence, with a greater risk of participating in aggressions. Thus, bullying others may sometimes be a strategy to enhance status within a group, especially in individuals without social and academic skills which help them garner a positive reputation (Salmivalli, 2010; Estévez, Inglés, Emler, Martínez-Monteagudo, & Torregrosa, 2012; Sánchez, Ortega, & Menesini, 2012).

Unfortunately, not a great deal of research has been conducted on the impact of social support and reputation as key factors in understanding the process of victimization and aggression in school settings from the perspective of different bullying roles. In contrast, a large body of literature on bullying refers to victims solely as pupils who suffer from bullying and not as those who engage in it, as can been seen in the typical definition of bullying. However, there is sufficient evidence that some school students are both bullies and victims (Del Rey & Ortega, 2008; Chen, Cheng, & Ho, 2015; Salmivalli, 2014).

Interest in this sub-group has grown recently and it has been suggested that the traditional term of provocative victim should be modified to aggressive victim, since in many cases such behaviours are a response to impulsive reactions and provocation is not always present (Del Moral, Suárez, Villarreal, & Musitu, 2014). In addition, it has been shown that the profile of victim typically described in defintions of school bullying is not totally adequate, since in aggressive victims, the aggression is not always directed towards a weaker individual (Volk, Dane, & Marini, 2014).

The aim of this study was to determine the relationship between social support, in its family, school and peer group dimensions, and individuals’ social image, and the different forms of involvement in school bullying.

Method

Participants

Our sample comprised 769 adolescents enrolled in the 2nd (49.7%; SD =.500) and 3rd year (50.3%, SD = .500) of compulsory secondary education, aged between 13 and 17 years (M = 14.13, SD = .931), of both sexes (54% boys, 46% girls, SD = .501) from eight schools (50% state schools, 50% state-subsidised private schools) in the city of Talavera de la Reina (Castilla-La Mancha, Spain). Multistage stratified cluster sampling was used to select the participants. The sampling units were the state schools and the state-subsidised private schools, while the strata were the years groups (2nd and 3rd) until completing the sample (N = 769) for a confidence level of 97% and a margin of error of 3.2%

We selected the 2nd and 3rd years of lower secondary education, taking into account the prevalence of bullying, since the literature reports these year groups have the highest bullying rates (Calvete, Orue, Estévez, Villardón, & Padilla, 2010; Ortega, Calmaestra, & Mora, 2008).

Variables and instruments

The first instrument used was Kidscreen-52, which is a questionnaire assessing health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in child and adolescent population. The psychometric properties of the scale have been validated in European (Analitis et al., 2009) and Spanish population. The dimensions of the Spanish version of the questionnaire presented less than 5% of missing values (acceptability) with acceptable percentages of responses in the upper and lower extremes of the distributions and high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha > .70) (Tebe et al., 2008).

The Spanish version of Kidscreen-52 comprises 52 items which measure ten dimensions, with each item showing adequate consistency (Aymerich et al., 2005). In the present study, to measure social family, peer group and school support, we used respectively the dimensions of parent relations and home life (Cronbach’s alpha = .87), social support and peers (Cronbach’s alpha = .82) and school environment (Cronbach’s alpha = .83), the reliability and internal consistency of which other studies have shown to be adequate (Analitis et al., 2009).

The dimension of parent relation and home life consists of six items rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale (two items: not at all, slightly, moderately, very, extremely; and three items: never, seldom, quite often, often, always). The dimensions of social support and peers and school environment each comprise six items scored on a five-point Likert-type scale (never, seldom, quite often, often, always). The score for each dimension corresponds to the sum of the responses to all the items (1-5) in the sub-scale.

Also administered were the Peer Victimization Scale (Cava, Musitu, & Murgui, 2007), an adaptation of the Victimization Scale (Mynard & Joseph, 2000) and the Social Experience Questionnaire (Crick & Grotpeter, 1996), comprising 22 items. The first 20 items, which are scored on a 4-point Likert-type scale (never, rarely, often, always) measure three dimensions: relational victimization (e.g., I have been ignored or treated with indifference by a classmate), manifest physical violence (e.g., I have been threatened by a classmate) and manifest verbal victimization (e.g., I have been shouted at by a classmate), which explained 62.18% of the variance (49.26%, 7.05% y 5.87%, respectively) in a factor analysis with oblimin rotation (Cava et al., 2007).

In addition, the Reputation Enhancement Scale (Carroll, Houghton, Hattie, & Durkin, 1999) was administered. It is composed of two factors, each of which are divided into three dimensions. The Self-perception factor comprises three dimensions: non-conforming self-perception (e.g., I’m a bad kid, or I break rules), conforming self-perception (e.g., I’m a good person, or I can be trusted with secrets) and reputational self-perception (e.g., I’m popular or I’m a leader). Ideal public self is composed of three dimensions: non-conforming ideal public self, conforming ideal public self, and reputational ideal public self, which measure how the respondent would ideally like to be viewed as regards their non-conforming behaviour, conforming behaviour and reputation and status, using the same item as in the self-perception factor. The items are scored on a four-point Likert-type scale (never, sometimes, often, always). The psychometric properties of the scale have been tested, confirming its validity and reliability (Carroll et al., 1999; Carroll, Green, Houghton, & Wood, 2003; Buelga, Musitu, & Murgui, 2009; Moreno, Estévez, Murgui, & Musitu, 2009a) and studies have reported its significant correlation with violent behaviour and capacity to discriminate between those involved and uninvolved in violent behaviours (Estévez, Jiménez, & Moreno, 2011; Carroll, Hattie, Houghton, & Durkin, 2001).

Finally, we also included the affiliation dimension from the Classroom Climate Scale (Moos & Trickett, 1973), adapted by Fernández-Ballesteros and Sierra (1989), which measures the perception of friendship and working together (e.g., in this class you can make lots of friends, or students in this class get to know each other well), the reliability and validity of which has been demonstrated in a number of studies. It has been shown that affiliation is positively related to self-esteem and life satisfaction and negatively associated with loneliness, depression, violence and school victimization (Cava, 2011; Cava, Musitu, Buelga, & Murgui, 2010; Estévez et al., 2008).

Procedure

Data were collected by self-report in group sessions in each year group’s classroom, using independent, anonymous booklets containing instructions. The questionnaires were administered by a member of the research team, who resolved any doubts when necessary, and gave instructions on how to complete the scales.

Prior to this, we requested the cooperation of the principals of the randomly selected sample of schools in Talavera de la Reina, sending them a written request to participate in the study, accompanied by an invitation and authorization from the Toledo Provincial Department of Education. We contacted the schools to arrange dates and times once the minors’ legal guardians had given their informed consent for them to complete the questionnaires. The anonymous, voluntary and confidential nature of the information provided was emphasized.

Statistical analyses

Taking as our reference the frequency of having engaged in bullying or having been victimized, which is considered to be a reliable indicator to differentiate between roles in bullying situations in schools (Velderman, van Dorst, Wiefferin, Detmar, & Paulussen, 2011), we established the variable of participants. This new variable was then divided into four categories: non-involved (never or seldom), bullies (have often or very often engaged in one of the types of bullying evaluated), victims (have often or very often suffered one of the types of bullying evaluated) and bully-victims (have often or very been bullied or victimized).

For purposes of comparison, the Kidscreen variables are typically converted to values with a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10. In the present study, all scores were typified in this way.

First, a descriptive analysis of the study variables was conducted, comparing gender-related differences, using χ2 or the t-test depending on the nature of each variable.

In addition, we compared all the school-related differences in bullying and victimization levels using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Games-Howell as a post-hoc test. Because we found one school with significant differences in both variables, the variable was recoded into two categories, grouping together the other schools, and again using χ 2 and the t-test to determine the possible differences in the remaining variables.

Subsequently, correlation analysis was used to determine the relationships between the different variables, while an ANOVA was used to compare differences in bullying, victimization, social support and self-perception across the groups of participants. Finally, a multivariate analysis, specifically a multinomial logistic regression, was conducted with the aim of determining whether the study variables were able to discriminate between the different individuals involved (bullies, victims and bully-victims).

Results

Regarding the prevalence of participation in school bullying, 32.1% of the students reported never having been involved or having sometimes been involved. A total of 27.6% had bullied, 13.1% had been victims, and 27.2% bully-victims. Boys were involved more as pure bullies (31.6% vs 22.9%) and less as pure victims (11.2% vs 15.4%). Significant differences were found between boys and girls (chi square = 8.206; p = .042), with a lower percentage of girls involved as pure bullies (31.6% vs 22.9%).

The comparison of means by gender revealed that boys exhibited significantly higher levels of aggression (t = 4.16, p = .000), parental support (t = 4.35, p = .000), non-conforming self-perception (t = 4.16, p= .000) and reputation (t = 2.27, p = 0.23). The girls presented higher conforming behaviour (t = -2.94, p = .003). We checked whether there were differences as regards types of victimization, finding that the girls scored significantly higher on relational victimization (t (674.01) = -3.53; p = .000) and the boys higher on physical victimization (t (764.35) = 2.52; p = .006).

In addition, we analysed the variables of aggression, victimization, social support and participants by school. Of the eight schools studied, one had significantly high levels of bullying and victimization (Brown-Forsythe = 8.77; gl 7-304.69, p = .000; Brown-Forsythe = 4.64; gl 7-613.2; p = .000), resulting in a significantly higher level of bully-victim prevalence (45.6% vs. 24.3%; χ 2 =22.964, p = .000; gl=3). Students at this school scored lower on perceived school environment, affiliation and parental support, but not on perceived peer support.

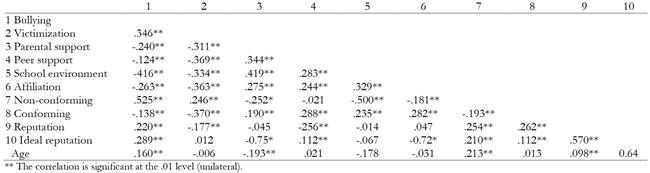

The correlation analyses showed that the three dimensions of the variables of social support and affiliation correlated negatively with both the level of bullying and the level of victimization. However, the relationship of school environment was higher with bullying (r = .416, p = .000), while in the other indicators of social support and affiliation, the relationship with victimization was more robust.

Regarding self-perception, both bullying and victimization positively correlated with non-conforming self-perception, but bullying was also positively correlated with reputation (r = .281, p = .000), while victimization was not (r = -.096, p = .000).

Non-conforming self-perception showed a very strong, negative relationship with support in the school environment. It was also related, albeit less significantly, to parental support and affiliation. Conforming self-perception was found to be positively related to all dimensions of social support and affiliation.

Reputation, however, was only related to peer support. As regards the dimensions of non-conforming and conforming ideal public self, the associations were highly similar to those of the dimensions of self-perception but less robust. Thus, they are not included in Table 1.

Ideal reputation was found to have a significant negative relationship with parental support and affiliation, which was not the case for self-perceived reputation.

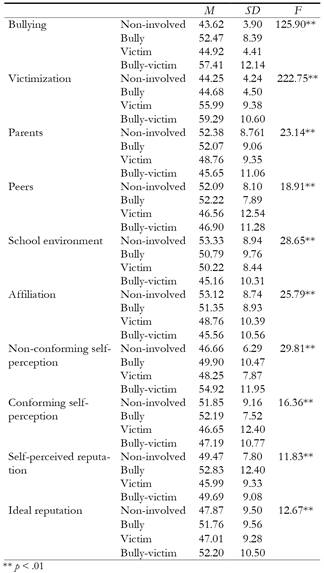

An ANOVA was used to compare the mean scores of the different groups of those involved for victimization, bullying, affiliation, self-perception and ideal reputation (Table 2).

The results of the post-hoc tests (Games-Howell) revealed that bully-victims were those who most bully but also those most victimized. Moreover, their perception of the school environment was significantly lower than that of the other groups, while they also scored higher on non-conforming self-perception.

The victims scored lowest on self-perceived reputation. In addition, they obtained similar scores to the bullies on support in the school environment, affiliation and non-conforming self-perception, and similar scores to the bully-victims on parental support, peer support and conforming self-perception. The bullies exhibited higher self-perceived reputation than the other groups, and, together with the bully-victims, also scored high on ideal reputation.

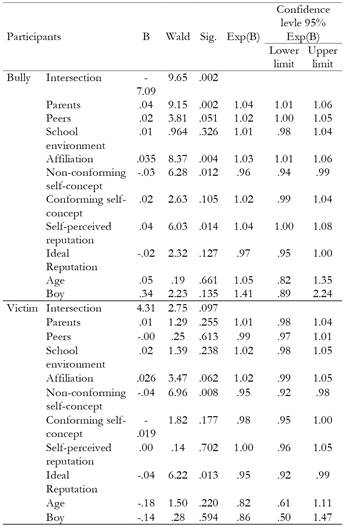

Finally, multinomial logistic regression analysis was used to determine whether the study variables were able to discriminate between the different groups of individuals involved and identify the variables characterizing each group.

The model obtained is significant (-2ll= 911.368; χ 2 =144.373, gl 20, p = .000; R 2 de Nagelkerke = .285) and correctly classifies 57.8% of the cases, performing better on bullies (70.3%) and bully-victims (62.4%) compared to victims (22.4%), which indicates the variables considered do not adequately characterize this group. Perceived school environment, gender and age are non-significant in the model.

If we take bully-victims as the reference, bullies show higher parental support, peer support and affiliation. They are also characterized by lower conforming self-perception but higher perceived reputation.

The victims, meanwhile, showed lower non-conforming self-perception and lower scores on ideal reputation.

Discussion

The results of this study show a strong inverse relationship between levels of bullying and victimization and the perception of peer support, family support and school support, as well as affiliation. Additionally, both variables are linked to a non-conforming perception. It is worth noting that the level of bullying is especially associated with a low perception of support in the school environment, and the level of victimization with lower parental and peer support and lower levels of affiliation.

The analysis by participant groups in this work might help explain why both bullying and victimization are significantly related to the same variables and in the same direction. Our results suggest that bully-victims are as prevalent as bullies and also present the highest levels of both bullying and victimization, bringing together the problems of both bullying and victimized behaviours in the same individual. These findings coincide with those of international research, which describes aggressive victims as especially maladaptive, unpopular and highly victimized, presenting symptoms of hyperactivity, anxiety and depression (Burk et al., 2011; Kelly et al., 2015; Yang & Salmivalli, 2013).

Another finding that confirms the role of bully-victims in the phenomenon of school bullying is that the school with the highest levels of bullying and victimization is also characterized by a significantly high prevalence of bully-victims, but not of pure bullies or pure victims.

Our findings on social support are in line with those of most of the research on bullying. The evidence that high perceived support from peer group, family and school reduces the risk of victimization and bullying appears to be robust (Fanti et al., 2012; Rothon, Head, Klineberg, & Stansfeld, 2011; Wang et al., 2009; Yaban et al., 2013). In this sense, perceived social support is generally viewed as a risk factor and a protective factor for both bullying and victimization (Fanti et al., 2012; Kendrick et al., 2012; Lambert & Cashwell, 2004; Rueger et al., 2010).

Nonetheless, from this perspective of risk, some of the questions regarding the role of social support are still unsolved. For example, it remains to be explained why, in some school students, low perceived social support enhances the risk of bullying and, in others, the risk of victimization (and in a third group, both). Hence, in recent years, there has been growing support for the idea that the relationship may be inverse, that perceived social support might be affected by involvement in bullying (Salmivalli, 2010). In our case, we believe that some of the findings of the present study are inconsistent with the traditional perspective of risk and could fit better in the perspective of quality of life.

Regarding peers, it is worth noting that the perceived support of friends correlates more highly with the other measures of perceived support compared with affiliation, which is also an indicator of relations with classmates and schoolmates. Arguably, this is a greater reflection of perceived support from school students, in any dimension, than the quality of relationships with peers at school.

Our findings on parental support show that low perceived family social support is associated with a higher level of victimization and is characteristic of both bully-victims and pure victims. The risk perspective holds that parental social support reduces the prevalence of intimidation and victimization (Collins & Laursen, 2004; Yaban et al., 2013) as it provides family support, emotional security and functional interaction styles (Parke, 2004). However, this hypothesis fails to explain why our findings show that bullies, who also present a dysfunctional relationship style, perceive greater parental support than victims. This question is typically unresolved in many studies on bullying or the relationship is assumed to be moderated by other factors, such as individual traits (Moreno, Estévez, Murgui, & Musitu, 2009b) or the perception of relations at school (Guerra et al., 2012; Martínez, Musitu, Amador, & Monreal, 2012).

As regards perceived support at school, it has also been considered an important predictor of bullying (Richard, Schneider, & Mallet, 2012), with victims showing lower levels of support from teachers and lower perceived safety at school (Berkowitz & Benbenishty, 2012; RasKauskas, Gregory, Harvey, Rifshana, & Evans, 2010). Our findings suggest that all those involved exhibit low perceived school support, although it is more strongly associated with bullying than with victimization. However, we consider it important that perceived school support is more linked to an individual’s non-conforming self-image than affiliation. In other words, it appears to be more associated with an adolescent’s behaviour at school than with their relationships at school

Taking into consideration the overall results of the present study as regards social support and affiliation, it might be that the perception of social support is impacted in all the participants, and rather than a risk or protective factor, it reflects how bullying affects school students’ quality of life. This interpretation might also help explain the similarities and differences between the groups of participants.

In the case of the bullies, their scores on perceived support would appear to be indicators of how their environment reacts to their aggressive behaviour; that is, it shows the rejection of family, classmates and teachers to their non-conforming behaviour, which coincides with the evidence available on school rejection (Estévez, Martínez, & Jiménez, 2009). In our results, only perceived peer support is unaffected by non-conforming image, which coincides with the literature on antisocial behaviour and the tendency of those with behavioural problems to associate with similar individuals and to show mutual self-acceptance (Bartolomé, Montañés, & Montañés, 2008), and with the evidence that bullies tend to be accepted by their circle of friends but rejected by the rest (Dijkstra, Lindenberg, & Veenstra, 2008; Dishion & Dodge, 2005; Rodríguez, 2015).

In contrast, in the case of the victims, the variables appear to reflect a lack of reaction in their environment to the harm they suffer, as evidenced by Malecki and Demaray (2002), who also found victims to be the group that most values social support. In this line, there is evidence that victims’ parents have difficulties in identifying the bullying of their children, recognizing bullying, appreciating its impact on their children and responding appropriately, which may be perceived by children as a lack of support (Sawyer, Mishna, Pepler, & Wiener, 2011). Similar problems in detecting and evaluating bullying have been described in teachers (Yoon & Kerber, 2000; Kazdin & Rotella, 2009). Finally, as is the case with bullies, some studies have shown that victims tend to associate with others like themselves, and hence have more difficulty in reacting to protect others. Indeed, the continuity of victimization over time depends on whether school students have friendships or not with other victims (Farmer, et al. 2013).

It is our opinion that our results on perceived reputation also appear to support this interpretation. Perceived reputation is significantly higher in bullies and is associated with a high level of perceived peer support, which, as already seen, is not affected by non-conforming image, and is independent of the other indicators of social support and affiliation. These findings are in line with those of other studies underlining that reputation, especially an individual’s desire to enhance their reputation, might favour the perpetration of bullying behaviours (Buelga, Iranzo, Cava, & Torralba, 2015; Estévez, Emler, Cava, & Inglés, 2014; Estévez et al., 2012; Moreno et al., 2009a; Garandeau, Lee, & Salmivalli, 2014). In our view, however, this reputation is that within their peer group, whereas previously mentioned, friends tend to exhibit similar behaviours. Thus, we find that bullies’ non-conforming behaviour is rejected by both parents and school environment, but they tend to have a good perceived reputation (and a wish to enhance this) among their peer group.

Finally, it is worth highlighting that perceived support, affiliation and the dimensions of self-perception do not allow us to adequately characterize pure victims. Indeed, victims exhibit low scores on all these dimensions, but do not differ greatly from the others involved. In this sense, it might be said they form a group that feels “invisible”, that does not perceive itself as supported or as having a reputation and does not seem to have any significant desire to improve this lack of reputation.

Our findings demonstrate that involvement in maltreatment at school is a common but complex phenomenon, in which, albeit at a moderate level, the majority of school students are involved. They also suggest that the association between the different relational variables and involvement in bullying may be bi-directional, forming a process of continuing interaction. We coincide with Salmivalli (2010) in that, despite the vast body of literature on school bullying, the processes of interaction involved are still insufficiently understood.

This complexity should be taken into account in interventions, especially given that bullying intervention and prevention programmes have been shown to have limited effectiveness (Ferguson, San Miguel, Kilburn, & Sánchez, 2007; Merrell, Gueldne, Ross, & Isava, 2008; Richard et al., 2012). For example, mobilizing the peer group to support the victim is considered a crucial response to situations of aggression (Salmivalli, 2010), but without ignoring that a large number of victims are also bullies, which would affect how they are perceived by other schoolmates. Indeed, it should also be recognized that the aggression they are exposed to might be part of a scenario of mutual bullying, given that there is sufficient evidence to suggest there exists both a process of influence and friend selection which leads to the most aggressive students establishing friendships with other aggressive peers, consequently increasing the risk of victimization (Bartolomé et al., 2008; Ettekal, Kochenderfer-Ladd, & Ladd, 2015). It is equally demonstrated that a great deal of bullying occurs between friends (Mishna, Wiener, & Pepler, 2008). This evidence, often ignored in research and interventions on bullying, is consistent with our findings, as previously mentioned.

In this sense, further research is required to establish whether this group is actually composed of aggressive victims, as tends to be assumed, or by victimized aggressors. Alternatively, a new approach is arguably required, since the very way this group is characterized may be biasing the interpretation of results and interventions. In this line, longitudinal studies are a promising direction (Salmivalli, 2010).

In addition, the tendency to classify school-aged children as bullies or victims is common both inside and outside school contexts and is even reflected in protocols provided for in schools (for example, Government of the Canary Islands, 1999; Regional Government of Cantabria, n.d.). This, however, disregards the significant reality that a large number of those involved in bullying, and in turn, are also bullied.

Interventions with peers, teachers and parents could then improve the effectiveness of such programmes, but holistic approaches are needed (Galloway & Roland, 2004). These should be based on sound knowledge of the group processes involved and the social context in which they occur (Patton, Eshmann, & Butler, 2013). In this sense, it would be useful to evaluate the response of the social and family environment, not necessarily as a precedent but also as the outcome of the adolescents’ behaviour.

Our findings, however, should be taken with some caution since the study is cross-sectional and correlational and thus causal relationships cannot be inferred. Moreover, interpreting the results with relation to social support or self-perception is debatable. But we believe our findings provide interesting information that serves to open the door to novel approaches on school relations and their impact on the healthy development of school students.

texto en

texto en